Practice Essentials

This article discusses mass lesions of the mesentery, including nonprimary tumors with manifestations related to the mesentery. Mesenteric tumors are uncommon lesions that are generally considered inclusive of similar lesions of the omentum. Primarily anecdotal references to this class of tumors have been made since the beginning of the 20th century. In 1936, Hart provided the earliest clear description of solid mesenteric tumors. As experience has accumulated in treating these lesions, a more complete picture of the various disease types that manifest as mesenteric masses has emerged.

Mesenteric tumors may be cystic or solid, and they may demonstrate malignant or benign clinical behavior. Although uncommon, they are encountered in all age groups from infancy to the very elderly. These tumors should be considered as an explanation for a palpable abdominal mass, but they are most commonly brought into the differential diagnosis of abdominal pathology once a suggestive radiologic study or an abdominal operation has been performed. An increased awareness of neoplastic and nonneoplastic processes that result in mesenteric masses aids the clinician in recognizing these diseases.

Mesenteric masses and lymphadenopathy shown to be related to infection are best treated with appropriately directed antimicrobial therapy. (See Treatment.) Sclerosing mesenteritis has been treated with antimetabolites. Mesenteric lymphoma is treated with cytotoxic chemotherapy. Mesenteric desmoid tumors have been reported to respond to various pharmacologic treatments; radiation therapy may be an option for unresectable, partially resectable, or recurrent mesenteric desmoid tumors.

Surgical treatment of benign mesenteric masses generally consists of local excision for smaller lesions. For malignant mesenteric tumors, the therapy of greatest demonstrated benefit is surgical, with the goal of removing gross disease with tumor-free margins of resection; this may involve en-bloc resection of other involved structures. Mesenteric desmoid tumors are very difficult lesions to treat surgically. Mesenteric lymphoma is not usually treated surgically; surgery is best used diagnostically when the diagnosis is probable but uncertain. Mesenteric carcinoid tumors are treated by resecting the mesenteric masses. Treatment of Castleman disease should consist of local resection of the lymph node mass.

Anatomy

The mesentery of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract consists of a contiguous, fibrofatty, fanlike structure containing arterial, venous, lymphatic, and neural structures coursing to and from the intestine, along the intestine's entire length.

The small-bowel mesentery and portions of the large-bowel mesentery are mobile within the peritoneal cavity. The mesenteries of the ascending and descending colon become fixed against the retroperitoneum during the normal course of fetal development. The greater and lesser omenta are also technically mesenteric in nature, and any consideration of tumors of these structures is generally inclusive of lesions of the greater and lesser omenta as well.

The vast majority of reported mesenteric tumors originate in the small-bowel mesentery or omentum. Mesenteric masses can arise as primary tumors, metastatic implants or lymph node involvement, or cellular proliferation secondary to infectious or inflammatory processes.

Pathophysiology

Clinical findings and symptoms associated with mesenteric tumors of all types are related to the presence of a mass lesion. Because the mass does not involve the tubular portion of the GI tract per se, obstructive symptoms are generally late findings in malignant mesenteric tumors and large benign tumors.

Without question, pain is the principal manifestation of mesenteric masses in adults and older children. A visceral pattern of pain may be related to mass effect within the peritoneum or to traction on the mesentery. This is generally deep and poorly localized discomfort, frequently described as central within the abdomen.

Benign mesenteric masses

These lesions are almost exclusively found in the mesentery of the small intestine, though cysts of the colonic mesentery have also been described. The incidence of cystic mesenteric masses in the United States is estimated at 1 per 100,000. [1] Most are lymphangiomas, [2, 3] but simple mesenteric cysts, enteric (duplication) cysts, pseudocysts, lipomas, and fibromas are also found, as well as rare benign mesenteric mesotheliomas with prominent cystic components.

Cystic lymphangiomas result from failed lymphatic channel development, resulting in lymphangiectasias and cysts. Patients are usually asymptomatic but can develop symptoms related to interval growth of the mass or as a result of complications (eg, rupture, superinfection, intracystic hemorrhage, or volvulus). [1] Cysts of the mesentery can become quite large before diagnosis (see the image below) and cause indolent symptoms that prompt workup and eventual treatment.

Massive mesenteric cyst that proved to be multiloculated lymphangioma. This large but benign structure had developed on narrow attachment to base of small-bowel mesentery and was amenable to excision without endangering any other mesenteric structures.

Massive mesenteric cyst that proved to be multiloculated lymphangioma. This large but benign structure had developed on narrow attachment to base of small-bowel mesentery and was amenable to excision without endangering any other mesenteric structures.

Other benign neoplasms of the mesentery are rare, but lipomas, neurogenic tumors, hamartomas, [4] and stromal tumors of small size with nonaggressive clinical behavior have been described. Actinomycosis and Whipple disease are infections that cause mesenteric masses from abscesses with granulation tissue and lymphadenopathy, respectively. [1]

Malignant mesenteric tumors

A relatively few tumor types account for the vast majority of mesenteric malignancies; in these malignancies, the small-bowel mesentery is almost exclusively the site of involvement.

Primary malignant mesenchymal or stromal tumors of the mesentery of the bowel (see the image below), as well as of the greater and lesser omenta, are a rare subset of abdominal cancers that resemble either retroperitoneal sarcomas or GI stromal tumors (GISTs) primary to the intestine. [5, 6, 7] In the past, many of these have been described as leiomyosarcomas. [8, 9]

Liposarcomas are locally aggressive malignancies with high risk of local recurrence after complete resection. Distant metastasis can occur in more poorly differentiated cancers of this type. Miettinen et al reported that in a group of 26 cases analyzed by the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, the incidence of omental and mesenteric tumors was roughly equal. [10]

Characterization of protein markers of this tumor type has indicated that they are phenotypically very similar to the GIST group and are less often related to retroperitoneal stromal tumors. The absence of a detectable primary intestinal tumor signifies a primary mesenteric origin of the lesion.

Solitary fibrous peritoneal tumors have also been described, which may be benign or malignant. These much more commonly arise from pleural tissue in the chest, but mesentery is one of the described extrathoracic locations. [1] Extrathoracic locations have a higher incidence of malignancy, an increased recurrence rate after surgical resection, and the potential for distant metastasis.

Patients with mesenteric tumors can exhibit signs and symptoms of intestinal obstruction; however, in contrast to primary tumors of the intestine, much bulkier disease may be present before obstructive findings are encountered.

Desmoid tumors of mesentery

Mesenteric desmoid tumors are a relatively infrequent but potentially life-threatening complication of familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP). [11, 12] The incidence of desmoid tumors is 2.4-4.3 per 100,000 in the general population, whereas the frequency is in the range of 4-32% in patients with FAP. [1] These tumors are areas of progressive fibroblastic and fibrous proliferation within the mesentery (and, less frequently, the retroperitoneum) that can locally involve vascular structures and can constrict and obstruct the bowel or the ureters. Although described as histologically benign, their infiltrative pattern of growth can ultimately lead to life-threatening patterns of visceral involvement. [13]

Sporadically occurring desmoid tumors are more numerous than those observed in FAP, though the cumulative risk of the development of these lesions is far greater in patients with FAP. Desmoid tumor is the second leading cause of death in patients with FAP. Sporadic mesenteric desmoid tumors are known to occur after trauma (eg, previous surgery), albeit rarely. [14, 15]

Although a causative relationship in desmoid formation has not been firmly established, various mutations of the APC gene have been identified in these tumors. [16] Desmoid tumors are more frequently associated with disease-causing mutations distal to codon 1444 of APC.

Mesothelioma

Although far less frequent than pleural disease, mesenteric mesothelioma related to visceral peritoneum has been reported in anecdotal cases for which surgical treatment of small-bowel obstruction was necessary. [17]

Mesenteric lymphoma

Lymphoma is the most common mesenteric malignancy, mostly consisting of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. [18] Primary mesenteric lymphoma, in contrast to primary small-bowel lymphoma, is a disease of the mesenteric lymph nodes that may represent a localized process or a component of a more disseminated pattern of disease. The clinical presentation of mesenteric lymphoma is much like that of other mesenteric tumors, with abdominal pain and palpable mass as the principal findings.

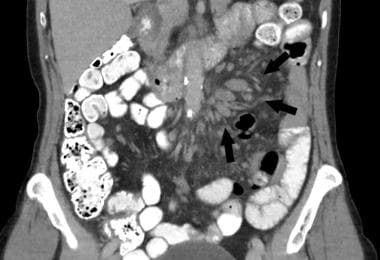

Computed tomography (CT) can characterize the lesion from the standpoint of size and mesenteric location and can raise the probability of the lymphoma diagnosis, though the finding of multiple enlarged lymph nodes raises other diagnostic possibilities. The typical CT image is of homogeneously enhancing lymphadenopathy (see the image below), generally adjacent to and sometimes encasing the mesenteric vessels with an intact perivascular border. The follicular centroblastic-centrocytic histologic type of lymphoma has been shown to predominate at mesenteric sites. [19]

Cluster of enlarged lymph nodes (arrows) in small-bowel mesentery, which on laparoscopic biopsy proved to be B-cell (follicular) lymphoma.

Cluster of enlarged lymph nodes (arrows) in small-bowel mesentery, which on laparoscopic biopsy proved to be B-cell (follicular) lymphoma.

The vast majority of metastatic lesions of the mesentery consist of mesenteric lymph nodes that have become secondarily involved in a neoplastic process of the GI tract. Distinguishing this pattern of tumor growth from primary mesenteric tumors usually presents no difficulty because the GI primary tumor site is generally identifiable.

Mesenteric carcinoid tumors

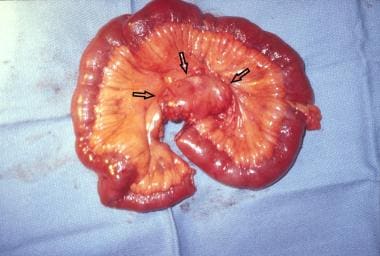

Carcinoid tumors of the small intestine are metastatic to mesenteric lymph nodes at the time of diagnosis in 40-50% of patients, though almost all such tumors that are greater than 2 cm in diameter have associated nodal involvement. Of these, a small subset may have minimal obvious disease within the small intestine and large mesenteric nodal metastases that may account for the vast majority of the tumor burden (see the image below). In addition, primary mesenteric carcinoids have been described that have been assumed to arise de novo in mesenteric tissues, though the veracity of this assumption is uncertain.

Mesenteric lymph node mass with metastatic involvement of small-bowel carcinoid. This was resected en bloc along with segment of small bowel within arterial blood supply distribution affected by removal of mass. This small intestine contained subcentimeter primary carcinoid tumor.

Mesenteric lymph node mass with metastatic involvement of small-bowel carcinoid. This was resected en bloc along with segment of small bowel within arterial blood supply distribution affected by removal of mass. This small intestine contained subcentimeter primary carcinoid tumor.

Liver metastases may be present in patients with metastatic mesenteric carcinoid tumors. Nuclear medicine studies (including indium-111 pentetreotide or I-131 metaiodobenzylguanidine [MIBG]) can be used to confirm the diagnosis. [20] This pattern of disease may be accompanied by extrinsic compression and occlusion of the mesenteric arterial blood supply and segmental ischemia or infarction of the intestine. Extensive carcinoid tumor involvement of small-bowel mesentery has been reported in association with a malabsorption syndrome.

Sclerosing mesenteritis

Sclerosing mesenteritis is an umbrella term used to describe a rare idiopathic inflammatory and fibrotic disease of the mesentery. It is often described interchangeably as mesenteric lipodystrophy, mesenteric panniculitis, or retractile mesenteritis, though these terms could be used to describe a predominating histologic appearance corresponding to fat necrosis, inflammatory changes, or fibrotic features. [21, 1]

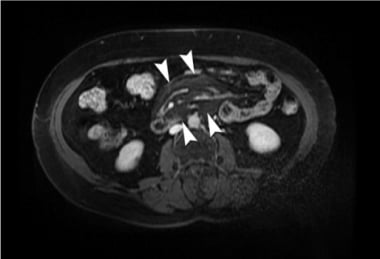

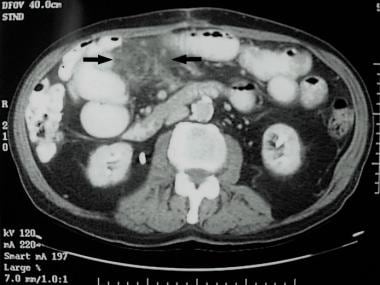

This condition can be mistaken for a mesenteric neoplasm on the basis of clinical, radiologic, and gross characteristics. It is a mesenteric thickening or mass that can be nodular in consistency and either focal or diffuse within the small-bowel mesentery. The root of the mesentery and the tissues surrounding the superior mesenteric vessels are commonly involved. CT or MRI may show the “fat ring sign,” denoting preservation of a fatty halo around the vessels (see the first image below), or “misty mesentery,” referring to hyperattenuation (see the second image below). [1]

Axial contrast-enhanced MRI of central hyperintense fatty mesenteric mass with preservation of fat around vessels and lymph nodes with "fat ring" or “halo” sign (arrows) consistent with mesenteritis. Courtesy of BioMed Central Ltd, Springer Nature [Arda K, Kizilkanat KT, Aydin H. CT and MRI aspect of mesenteric panniculitis. J Case Rep Med 7. 2018 Jun 30.]

Axial contrast-enhanced MRI of central hyperintense fatty mesenteric mass with preservation of fat around vessels and lymph nodes with "fat ring" or “halo” sign (arrows) consistent with mesenteritis. Courtesy of BioMed Central Ltd, Springer Nature [Arda K, Kizilkanat KT, Aydin H. CT and MRI aspect of mesenteric panniculitis. J Case Rep Med 7. 2018 Jun 30.]

CT image of increased mesenteric tissue density or “misty mesentery” (between arrows), which laparoscopic incisional biopsy demonstrated was sclerosing mesenteritis.

CT image of increased mesenteric tissue density or “misty mesentery” (between arrows), which laparoscopic incisional biopsy demonstrated was sclerosing mesenteritis.

The mass may consist of hypertrophied fatty tissue, dense fibrous tissue, fat necrosis, or combinations of these, along with a nonspecific chronic inflammatory infiltrate. Its presenting symptom is abdominal pain in most patients, though it has been anecdotally reported in association with fever, mesenteric calcifications, and protein-losing enteropathy.The cause of this condition is unknown, though associations with abdominal trauma, abdominal surgery, malignancy, and autoimmune diseases have been reported.

Treatment includes medical and surgical management, though the diagnosis is confirmed on operative biopsy. Other than a focal area of mesenteric thickening and induration, the affected tissues have no particular gross distinguishing features. Biopsy must be done with care to avoid mesenteric vascular injury. Because the problem most frequently involves more central areas of the mesentery, complete resection is not commonly possible. In patients with significant pain symptoms, there are options for medical management (see Medical Therapy). Rare cases of retractile mesenteritis with fibrosis that impairs intestinal perfusion have been reported, necessitating surgical resection for acute segmental ischemia.

Mesenteric lymphadenopathy

Infectious etiologies of mesenteric lymph node enlargement include bacterial infection, mycobacterial infection, and histoplasmosis. A large number of these cases have been reported in conjunction with HIV infection. Although lymphadenopathy is usually generalized in tuberculosis, mesenteric lymphadenitis has been described as the principal presenting problem.

Castleman disease (giant lymph node hyperplasia) is a rare condition usually observed in the mediastinum. The even rarer cases in the abdomen are most frequently retroperitoneal, but cases of isolated mesenteric disease have been reported. [22] It can be classified as unicentric or multicentric.

The etiology of Castleman disease is not well known. In addition to HIV infection, it can be seen in association with herpesvirus 8, Kaposi sarcoma, Hodgkin disease, and non-Hodgkin disease. [1] The estimated prevalence of Castleman disease ranges from 1 in 30,000 to 1 in 100,000 in the United States. The diagnosis is generally inferred from imaging studies and confirmed with histology. The differential diagnosis includes consideration of primary lymphoid neoplasms and metastatic lymph node involvement. [23] Sarcoid has been reported as a cause of localized bulky mesenteric lymphadenopathy as well.

Etiology

No known etiologic or associated diseases have been reported in cases of primary mesenteric neoplasms. Reactive lymphadenopathy within the mesentery may be a manifestation of systemic, often infectious, disease.

Epidemiology

Solid primary tumors of the mesentery are rare. Published reports have consisted of small numbers of cases, which makes it difficult to determine the incidence of specific tumor types. Reasonable estimates of incidence have ranged from 1 case per 200,000 to 1 case per 350,000 population. Mesenteric tumors have been described as cystic in 40-60% of cases. [24]

Numerous anecdotal reports of mesenteric lipomas in adults and children have appeared over the years, suggesting that these probably represent the most frequently encountered symptom-causing solid tumors of primary mesenteric origin.

Malignant primary mesenteric tumors are extremely uncommon, even compared with primary malignancies of the small bowel. Published reports suggest that one third to one half of all mesenteric masses are malignant tumors. The largest case series have been from France and China. [25, 26] Cook et al, using Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) program data, calculated male-to-female incidence rate ratios (IRRs) for various cancers for the period between 1975 and 2004. [27] According to their results, mesenteric cancer occurred more frequently in females than in males, with the overall male-to-female IRR for cancers of the peritoneum, omentum, and mesentery being 0.18.

Prognosis

The results of surgical treatment of benign cysts and solid tumors of the mesentery are very favorable. This is true of even large benign tumors, though local recurrence has been reported. Death as a consequence of benign masses, with the exception of mesenteric desmoid tumors, can be assumed to be an extremely unlikely event.

Because so few cases have been reported, long-term results of surgical treatment of malignant mesenteric mesenchymal tumors, which are histologically similar to GISTs, have not been well characterized. In fact, no large series reporting management and outcomes of treatment of this tumor type have been conducted. Published reports suggest that their biologic behavior is similar to that of primary GI mesenchymal malignancies.

A study of 114 mesenteric GISTs by Feng et al reported a 5-year disease-free survival rate of 57.7% and a 5-year disease-specific survival rate of 60.1%; these postoperative survival data were similar to those reported for intestinal GISTs. [28] This uncontrolled comparison did not accurately account for the use of imatinib, which has proved very effective in the treatment of c-Kit-positive intestinal GISTs. Other specific postoperative adjuvant or palliative therapies, such as cytotoxic chemotherapy or radiation therapy, have not been shown to be of benefit.

Intra-abdominal desmoid tumors are the second most frequent cause of death in FAP patients (after cancer-related deaths).

-

Massive mesenteric cyst that proved to be multiloculated lymphangioma. This large but benign structure had developed on narrow attachment to base of small-bowel mesentery and was amenable to excision without endangering any other mesenteric structures.

-

Cluster of enlarged lymph nodes (arrows) in small-bowel mesentery, which on laparoscopic biopsy proved to be B-cell (follicular) lymphoma.

-

Mesenteric lymph node mass with metastatic involvement of small-bowel carcinoid. This was resected en bloc along with segment of small bowel within arterial blood supply distribution affected by removal of mass. This small intestine contained subcentimeter primary carcinoid tumor.

-

Axial contrast-enhanced MRI of central hyperintense fatty mesenteric mass with preservation of fat around vessels and lymph nodes with "fat ring" or “halo” sign (arrows) consistent with mesenteritis. Courtesy of BioMed Central Ltd, Springer Nature [Arda K, Kizilkanat KT, Aydin H. CT and MRI aspect of mesenteric panniculitis. J Case Rep Med 7. 2018 Jun 30.]

-

CT image of increased mesenteric tissue density or “misty mesentery” (between arrows), which laparoscopic incisional biopsy demonstrated was sclerosing mesenteritis.

-

CT image of benign mesenteric lipoma. This discrete lesion (arrows) is homogeneous and has density of normal surrounding mesenteric fat.

-

Laparoscopic view of simple mesenteric cyst before laparoscopic excision.

-

Laparoscopic view of simple mesenteric cyst dissection bed after laparoscopic excision.

-

Mesenteric GIST-like tumor with solid and cystic components. Diagnosis was established after resection with demonstration of absence of primary GI tumor.

-

Resected mesenteric tumor. Operative treatment involved segmental small-bowel and colon resection. Large specimen size is evident.

-

Section of malignant mesenteric fatty tumor resected en bloc with obstructed, encased small intestine.