Practice Essentials

A fistula-in-ano is an abnormal hollow tract or cavity that is lined with granulation tissue and that connects a primary opening inside the anal canal to a secondary opening in the perianal skin; secondary tracts may be multiple and can extend from the same primary opening. It should be differentiated from the following processes, which do not communicate with the anal canal:

-

Hidradenitis suppurativa

-

Infected inclusion cysts

-

Pilonidal disease

-

Bartholin gland abscess in females

Most fistulas are thought to arise as a result of cryptoglandular infection with resultant perirectal abscess. The abscess represents the acute inflammatory event, whereas the fistula is representative of the chronic process. Symptoms generally affect quality of life significantly, and they range from minor discomfort and drainage with resultant hygienic problems to sepsis.

References to fistula-in-ano date to antiquity. The fascination fistula-in-ano has exerted for more than 2000 years is manifested by the numerous papers and books on the subject. Hippocrates, in about 430 BCE, made reference to surgical therapy for fistulous disease, and he was the first person to advocate the use of a seton (from Latin seta "bristle").

In 1376, the English surgeon John Arderne (1307-1390) wrote Treatises of Fistula in Ano; Haemmorhoids, and Clysters, which described fistulotomy and seton use. Historical references indicate that Louis XIV was treated for an anal fistula in the 18th century. Salmon established a hospital in London (St. Mark's) devoted to the treatment of fistula-in-ano and other rectal conditions. [1]

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, prominent physician/surgeons, such as Goodsall and Miles, Milligan and Morgan, Thompson, and Lockhart-Mummery, made substantial contributions to the treatment of anal fistula. These physicians offered theories on pathogenesis and classification systems for fistula-in-ano. [2, 3]

Since this early progress, little has changed in the understanding of the disease process. In 1976, Parks refined the classification system that is still in widespread use. Over the past few decades, many authors have presented new techniques and case series in an effort to minimize recurrence rates and incontinence complications, but despite more than two millennia of experience, fistula-in-ano remains a perplexing surgical disease.

Treatment of fistula-in-ano remains challenging. [4] No definitive medical therapy is available for this condition, though long-term antibiotic prophylaxis and infliximab may have a role in recurrent fistulas in patients with Crohn disease. Surgery is the treatment of choice, with the goals of draining infection, eradicating the fistulous tract, and avoiding persistent or recurrent disease while preserving anal sphincter function. [5, 6]

For patient education information, see the Digestive Disorders Center, as well as Anal Abscess, Rectal Pain, and Rectal Bleeding.

Anatomy

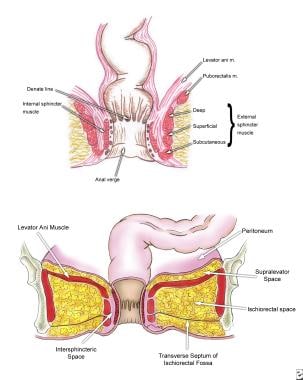

A thorough understanding of the pelvic floor and sphincter anatomy is a prerequisite for clearly understanding the classification system for fistulous disease. (See the image below.)

The external sphincter muscle is a striated muscle under voluntary control by three components: submucosal, superficial, and deep muscle. Its deep segment is continuous with the puborectalis and forms the anorectal ring, which is palpable upon digital examination.

The internal sphincter muscle is a smooth muscle under autonomic control and is an extension of the circular muscle of the rectum.

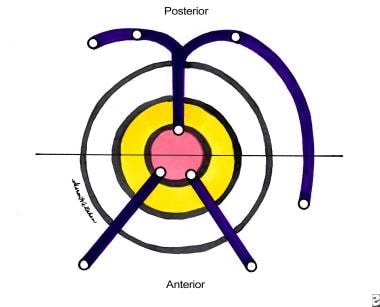

In simple cases, the Goodsall rule can help anticipate the anatomy of a fistula-in-ano. This rule states that fistulas with an external opening anterior to a plane passing transversely through the center of the anus will follow a straight radial course to the dentate line. Fistulas with their openings posterior to this line will follow a curved course to the posterior midline (see the image below). Exceptions to this rule are external openings lying more than 3 cm from the anal verge. These almost always originate as a primary or secondary tract from the posterior midline, consistent with a previous horseshoe abscess. [7, 8]

Parks classification system

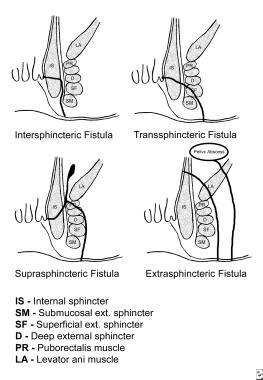

The classification system developed by Parks, Gordon, and Hardcastle (generally known as the Parks classification) is the one most commonly used for fistula-in-ano. This system (see the image below) defines four types of fistula-in-ano that result from cryptoglandular infections, as follows [9] :

-

Intersphincteric

-

Transsphincteric

-

Suprasphincteric

-

Extrasphincteric

An intersphincteric fistula-in-ano is characterized as follows:

-

It is the result of a perianal abscess

-

Common course - It begins at the dentate line, then tracks via the internal sphincter to the intersphincteric space between the internal and external anal sphincters, and finally terminates in the perianal skin or perineum

-

Incidence - 70% of all anal fistulas

-

Other possible tracts - No perineal opening; high blind tract; high tract to lower rectum or pelvis

A transsphincteric fistula-in-ano is characterized as follows:

-

In its usual variety, this fistula results from an ischiorectal fossa abscess

-

Common course - It tracks from the internal opening at the dentate line via the internal and external anal sphincters into the ischiorectal fossa and then terminates in the perianal skin or perineum

-

Incidence - 25% of all anal fistulas

-

Other possible tracts - High tract with perineal opening; high blind tract

A suprasphincteric fistula-in-ano is characterized as follows:

-

It arises from a supralevator abscess

-

Common course - It passes from the internal opening at the dentate line to the intersphincteric space, tracks superiorly to above the puborectalis, and then curves downward lateral to the external anal sphincter into the ischiorectal fossa and finally to the perianal skin or perineum

-

Incidence - 5% percent of all anal fistulas

-

Other possible tracts - High blind tract (ie, palpable through rectal wall above dentate line)

An extrasphincteric fistula-in-ano is characterized as follows:

-

It may arise from foreign body penetration of the rectum with drainage through the levators, from penetrating injury to the perineum, from Crohn disease or carcinoma or its treatment, or from pelvic inflammatory disease

-

Common course - It runs from the perianal skin via the ischiorectal fossa, tracking upward and through the levator ani muscles to the rectal wall, completely outside the sphincter mechanism, with or without a connection to the dentate line

-

Incidence - 1% of all anal fistulas

Current procedural terminology codes classification

Current procedural terminology coding includes the following:

-

Subcutaneous

-

Submuscular (intersphincteric, low transsphincteric)

-

Complex, recurrent (high transsphincteric, suprasphincteric and extrasphincteric, multiple tracts, recurrent)

-

Second stage

Unlike the current procedural terminology coding, the Parks and colleagues classification system developed by Parks et al does not include the subcutaneous fistula. These fistulas are not of cryptoglandular origin but are usually caused by unhealed anal fissures or anorectal procedures (eg, hemorrhoidectomy or sphincterotomy).

Etiology

In the vast majority of cases, fistula-in-ano is caused by a previous anorectal abscess. Typically, there are eight to 10 anal crypt glands at the level of the dentate line in the anal canal, arranged circumferentially. These glands penetrate the internal sphincter and end in the intersphincteric plane. They provide a path by which infecting organisms can reach the intramuscular spaces. The cryptoglandular hypothesis states that an infection begins in the anal canal glands and progresses into the muscular wall of the anal sphincters to cause an anorectal abscess.

After surgical or spontaneous drainage in the perianal skin, a granulation tissue–lined tract is occasionally left behind, causing recurrent symptoms. Multiple series have shown that formation of a fistula tract after anorectal abscess occurs in 7-40% of cases. [10, 11]

Other fistulas develop secondary to trauma (eg, rectal foreign bodies), Crohn disease, anal fissures, carcinoma, radiation therapy, actinomycoses, tuberculosis, and lymphogranuloma venereum secondary to chlamydial infection.

Epidemiology

The true prevalence of fistula-in-ano is unknown. The incidence of a fistula-in-ano developing from an anal abscess ranges from 26% to 38%. [5, 12] One study showed that the prevalence of fistula-in-ano is 8.6 cases per 100,000 population. In men, the prevalence is 12.3 cases per 100,000 population, and in women, it is 5.6 cases per 100,000 population. The male-to-female ratio is 1.8:1. The mean patient age is 38.3 years. [13]

-

Anatomy of the anal canal and perianal space.

-

Fistula-in-ano. Goodsall rule.

-

Parks classification of fistula-in-ano.

-

Schematic of intersphincteric and low transsphincteric fistulotomy.

-

Schematic of high transsphincteric fistulotomy with seton.