Practice Essentials

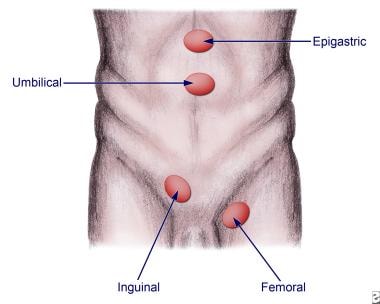

Abdominal wall hernias are among the most common of all surgical problems. Knowledge of these hernias (usual and unusual) and of protrusions that mimic them is an essential component of the armamentarium of the general and pediatric surgeon. More than 1 million abdominal wall hernia repairs are performed each year in the United States, with inguinal hernia repairs constituting nearly 770,000 of these cases; approximately 90% of all inguinal hernia repairs are performed on males. [1, 2, 3] See the image below.

Signs and symptoms

Hernias may be detected on routine physical examination, or patients with hernias may present because of a complication associated with the hernia.

Characteristics of asymptomatic hernias are as follows:

-

Swelling or fullness at the hernia site

-

Aching sensation (radiates into the area of the hernia)

-

No true pain or tenderness upon examination

-

Enlarges with increasing intra-abdominal pressure and/or standing

Characteristics of incarcerated hernias are as follows:

-

Painful enlargement of a previous hernia or defect

-

Cannot be manipulated (either spontaneously or manually) through the fascial defect

-

Nausea, vomiting, and symptoms of bowel obstruction (possible)

Characteristics of strangulated hernias are as follows:

-

Patients have symptoms of an incarcerated hernia

-

Systemic toxicity secondary to ischemic bowel is possible

-

Strangulation is probable if pain and tenderness of an incarcerated hernia persist after reduction

-

Suspect an alternative diagnosis in patients who have a substantial amount of pain without evidence of incarceration or strangulation

When attempting to identify a hernia, look for a swelling or mass in the area of the fascial defect, as follows:

-

For inguinal hernias, place a fingertip into the scrotal sac and advance up into the inguinal canal

-

If the hernia is elsewhere on the abdomen, attempt to define the borders of the fascial defect

-

If the hernia comes from superolateral to inferomedial and strikes the distal tip of the finger, it most likely is an indirect hernia

-

If the hernia strikes the pad of the finger from deep to superficial, it is more consistent with a direct hernia

-

A bulge felt below the inguinal ligament is consistent with a femoral hernia

Characteristics of various hernia types include the following:

-

Inguinal hernia - Bulge in the inguinal region or scrotum, sometimes intermittent; may be accompanied by a dull ache or burning pain, which often worsens with exercise or straining (eg, coughing)

-

Spigelian hernia - Local pain and signs of obstruction from incarceration; pain increases with contraction of the abdominal musculature

-

Interparietal hernia - Similar to spigelian hernia; occurs most frequently in previous incisions

-

Internal supravesical hernias - Symptoms of gastrointestinal (GI) obstruction or symptoms resembling a urinary tract infection

-

Lumbar hernia - Vague flank discomfort combined with an enlarging mass in the flank; progressive protrusion through lumbar triangles, more commonly through the superior (Grynfeltt-Lesshaft) triangle than through the inferior (Petit); not prone to incarceration

-

Obturator hernia - Intermittent, acute, and severe hyperesthesia or pain in the medial thigh or in the region of the greater trochanter, usually relieved by thigh flexion and worsened by medial rotation, adduction, or extension at the hip

-

Sciatic hernia - Tender mass in the gluteal area that is increasing in size; sciatic neuropathy and symptoms of intestinal or ureteral obstruction can also occur

-

Perineal hernias - Perineal mass with discomfort on sitting and occasionally obstructive symptoms with incarceration

-

Umbilical hernia - Central, midabdominal bulge

-

Epigastric hernia - Small lumps along the linea alba reflecting openings through which preperitoneal fat can protrude; may be adjacent to the umbilicus (umbilical hernia) or more cephalad (ventral hernia [epiplocele])

See Presentation for more detail.

History and physical examination remain the best means of diagnosing hernias. The review of systems should carefully seek out associated conditions, such as ascites, constipation, obstructive uropathy, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and cough.

Diagnosis

Laboratory studies include the following:

-

Stain or culture of nodal tissue

-

Complete blood count (CBC)

-

Electrolytes, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), and creatinine

-

Urinalysis

-

Lactate

Imaging studies are not required in the normal workup of a hernia. However, they may be useful in certain scenarios, as follows:

-

Ultrasonography (US) can be used in differentiating masses in the groin or abdominal wall or in differentiating testicular sources of swelling

-

If an incarcerated or strangulated hernia is suspected, upright chest films or flat and upright abdominal films may be obtained

-

Computed tomography (CT) or ultrasonography may be necessary if a good examination cannot be obtained, because of the patient’s body habitus, or in order to diagnose a spigelian or obturator hernia

See Workup for more detail.

Management

Nonoperative therapeutic measures include the following:

-

Trusses

-

Binders or corsets

-

Hernia reduction [1]

-

Topical therapy

-

Compression dressings

Surgical options depend on type and location of hernia. Basic types of inguinal hernia repair include the following:

-

Bassini repair

-

Shouldice repair

-

Cooper repair

-

Simple inguinal hernia repair in children

Surgical approaches to other hernia types may vary, as follows:

-

Umbilical hernia - After exposure of the umbilical sac, a plane is created to encircle the sac at the level of the fascial ring, and the defect is closed transversely with interrupted sutures; if the defect is very large (>2 cm), mesh may be required

-

Epigastric hernia - A small vertical incision directly over the defect is carried to the linea alba, and incarcerated preperitoneal fat is either excised or returned to the properitoneum; the defect is closed transversely with interrupted sutures

-

Spigelian hernia - A transverse incision over the hernia to the sac allows dissection to the neck, and clean approximation of the internal oblique muscle and the transversus abdominis followed by closure of the external oblique aponeurosis completes the repair

-

Interparietal hernia - Large interparietal hernias require mesh or component separation technique

-

Supravesical hernia - The standard techniques for inguinal and femoral hernias are used, usually via a paramedian or midline incision

-

Lumbar hernia - A skin-line oblique incision is made from the 12th rib to the iliac crest; a layered closure or mesh onlay for large defects is successful

-

Obturator hernia - Generally approached abdominally and often amenable to laparoscopic repair; mesh closure is necessary for a tension-free repair

-

Sciatic hernia - A transperitoneal approach is used in the event of incarceration; a transgluteal repair can be used if the diagnosis is established and the intestine is clearly viable

-

Perineal hernia - A transabdominal approach with prosthetic closure is preferred; a combined transabdominal-perineal approach can also be used

-

Gastroschisis and omphalocele - Primary closure of fascia and skin is usually best; nonoperative management of gastroschisis (plastic closure) is an alternative to conventional primary operative closure or staged silo closure

-

Femoral hernia - A standard Cooper ligament repair, a preperitoneal approach, or a laparoscopic approach may be used; the procedure includes dissection and reduction of the hernia sac and obliteration of the defect in the femoral canal by approximating the iliopubic tract to the pectineal (Cooper) ligament or by using a mesh

See Treatment and Medication for more detail.

Background

Uncommon in other animals, abdominal wall hernias are among the most common of all surgical problems. They are a leading cause of work loss and disability and are sometimes lethal. Knowledge of hernias of the abdominal wall (usual and unusual) and of the protrusions that mimic hernias is an essential component of the armamentarium of the general and pediatric surgeon.

Abdominal wall hernias are commonly described in terms of their anatomic location. Four of the most common types are shown in the image below.

Operative management of hernias, despite being described since antiquity and constituting an essential part of the general surgeon’s repertoire of operations, remains controversial. By definition, a hernia is an abnormal protrusion from one anatomic space to another, with the protruded parts generally contained in a saclike structure formed by the membrane that naturally lines the cavity.

Variants on the definition of hernia exist with regard to congenital abdominal wall defects. An omphalocele is characterized by extension of viscera from the abdominal cavity into the umbilical stalk, with the contents covered by a translucent, bilaminar sac consisting of fused amnion and peritoneum. On occasion, the sac tears prenatally or during delivery, thus becoming harder to identify. The underlying abdominal wall defect exceeds 4 cm. The umbilical vessels insert onto the sac and travel along its left superior aspect to the abdominal wall.

On the other hand, gastroschisis is present when midgut viscera protrude through a central abdominal fascial defect and are not covered by a sac. In this case, the extracorporeal viscera are exposed to the amniotic fluid in utero or to the atmosphere postnatally. The responsible fascial defect is usually less than 4 cm and is almost always immediately to the right and inferior to the umbilicus.

Anatomy

Anterior abdominal wall

The anterior abdominal wall is composed of multilaminar mirror-image muscles, the associated aponeuroses, fasciae, fat, and skin. Laterally, three muscle layers with fascicles run obliquely in relation to each other. Each inserts into a flat white tendon, known as an aponeurosis.

The paired rectus abdominis muscles originate on the pubis inferiorly and insert on the ribs superiorly. The muscle has four transversely oriented tendinous bands, variably spaced. At the lateral margin of the rectus abdominis muscles is the linea semilunaris, where the aponeurosis serves as an insertion for the lateral musculature. The lower edge of the posterior sheath, midway between the umbilicus and the pubis with its concavity oriented toward the pubis, defines the semicircular line.

Above this line, anterior and posterior laminae form from division of the internal oblique aponeurosis. The posterior lamina joins the transversus abdominis aponeurosis and forms the posterior rectus sheath. The anterior rectus sheath results from fusion of the anterior lamina and the external oblique aponeurosis. The external oblique aponeurosis forms the external lamina of the anterior sheath below the semicircular line. Fusion of the internal oblique and transversus abdominis aponeuroses forms the internal lamina of the anterior sheath.

The posterior surface of the rectus muscles is covered with transversalis fascia below the semicircular line. The midline linea alba represents a decussation of these fibers from the different aponeurotic layers.

The external oblique muscle originates on the lower eight ribs, with obliquely and inferiorly directed fascicles inserting into its aponeurosis. Deep to the external oblique muscle is the internal oblique muscle, with obliquely and superiorly oriented fascicles arising from the iliac fascia deep to the lateral half of the inguinal ligament, the anterior two thirds of the iliac crest, and the lumbodorsal fascia. The internal oblique muscle inserts into its aponeurosis, the rectus sheath, and the lower ribs and cartilages superiorly.

The transversus abdominis is the most internal of the lateral abdominal wall muscles. The fascicles generally are transversely oriented. The transversus abdominis arises from the lateral iliopubic tract, the iliac crest, the lumbodorsal fascia, and the caudad six ribs. It inserts principally into its aponeurosis and fuses with the internal oblique aponeurosis to become the posterior rectus sheath.

The caudad margin curves to form the transversus abdominis aponeurotic arch as the upper edge of the internal ring and above the medial floor of the inguinal canal. In 3% of cases, this arch may combine with the internal oblique aponeurosis to form the conjoined tendon.

The innominate fascia overlies the external oblique muscle. The transversalis fascia forms an investing fascial envelope of the abdominal cavity. A variable layer of preperitoneal fat separates the peritoneum from the transversalis fascia.

Posterolateral region

In the posterolateral (lumbar) region, the quadratus originates from the iliac crest and the iliolumbar ligament from between the iliac crest and the fifth lumbar transverse process. It then inserts along the 12th rib. The psoas arises from vertebrae T12-L5 and passes downward under the inguinal ligament to insert on the lesser trochanter.

The serratus posterior inferior originates from the lumbodorsal fascia and inserts along the four lowest ribs. The sacrospinalis runs along the spinous processes for the entire length of the spine.

The latissimus dorsi originates on the posterior third of the iliac crest, the spinous processes of the sacral and lumbar vertebrae, and the lumbodorsal fascia. From this wide origin, the muscle inserts as a tendon into the intertubercular groove of the humerus.

The superior lumbar triangle of Grynfeltt-Lesshaft is bounded superiorly by the 12th rib, the posterior lumbocostal ligament, and the serratus posterior inferior; inferiorly by the superior border of the internal oblique muscle; and posteriorly by the lateral border of the sacrospinalis. The deep margin of the superior lumbar triangle is the transversus abdominis, and the superficial margin is the latissimus dorsi. Spontaneous lumbar hernias occur more commonly because the potential space is larger and more constant than the inferior lumbar triangle.

The inferior lumbar triangle of Petit is bounded posteriorly by the latissimus dorsi, anteriorly by the external oblique muscle, and inferiorly by the iliac crest.

Inguinal region

Vessels regularly found during inguinal hernia repairs are the superficial circumflex iliac, superficial epigastric, and external pudendal arteries, which arise from the proximal femoral artery and course superiorly. The inferior epigastric artery and vein run medially and cephalad in the preperitoneal fat near the caudad margin of the internal inguinal ring.

The external iliac vessels pass posterior to the inguinal ligament and iliopubic tract and anterior to the pectineal ligament to enter the femoral sheath. The external spermatic artery arises from the inferior epigastric artery just caudad to the internal inguinal ring to supply the cremaster muscle.

The inguinal ligament bridges the space between the pubic tubercle and the anterior superior iliac spine and rotates posteriorly and then superiorly to form a shelving edge. It is the caudad edge of the external oblique aponeurosis. This ligament revolves medially to create the lacunar ligament, which inserts on the pubis and courses medially and superiorly toward the midline. The external oblique aponeurosis has a triangular opening with a superior apex, through which the cord enters the inguinal canal.

The transversus abdominis is the predominant abdominal wall layer for the prevention of inguinal hernias. The transversus abdominis aponeurotic arch inserts inferiorly on the Cooper ligament and contributes to the anterior rectus sheath medially.

The pectineal ligament courses from the superior part of the superior pubic ramus periosteum. The components incorporate fibers from the lacunar ligament, the transversus abdominis aponeurosis, and the pectineus.

An aponeurotic band from the caudad portion of the transversus abdominis creates the iliopubic tract. It is the anterior margin of the femoral sheath and the caudad border of the internal ring. The course is from the superior pubic ramus medially to the iliopectineal arch and iliopsoas fascia, anterior to the femoral vessels, and then laterally to the anterior superior iliac spine.

The iliacus fascia thickens as it exits the pelvis to form the iliopectineal arch. The fascia curves forward, lateral to the external iliac vessels, and combines with fibers from the inguinal ligament, from the internal oblique muscle and the transversus abdominis, and from part of the ligament lateral attachment of the iliopubic tract. The external iliac vessels pass beneath the inguinal ligament and iliopubic tract but anterior to the pectineal ligament to enter the femoral sheath.

The femoral sheath, with contributions from the transversalis, pectineus, psoas, and iliacus fasciae, has three compartments. A femoral hernia most often occurs in the most medial compartment. The femoral canal is bounded laterally by the femoral vein. The medial margin is the transversus abdominis aponeurosis insertion and transversalis fascia. The femoral canal holds lymphatic channels and lymph nodes.

The superolateral border of the Hesselbach triangle is the inferior epigastric vessels. The inguinal ligament constitutes the inferolateral side. The lateral edge of the rectus sheath is the medial side.

The internal ring is bordered by the transversalis fascia circumferentially and deep, the arch of the internal oblique and transversus abdominis muscles superomedially, and the iliopubic tract inferolaterally. The course of the spermatic cord or round ligament through the abdominal wall defines the inguinal canal. Transversus abdominis aponeurosis and transversalis fascia combine to make the floor of the inguinal canal in 75% of persons (a minority have only transversalis fascia). The external oblique aponeurosis is anterior, and the inguinal ligament is inferior.

The vas deferens and the testicular artery and vein constitute the spermatic cord. The innominate fascia extends onto the cord as the external spermatic fascia. The cremasteric fascia and the cremaster muscle extend from internal oblique muscle and its aponeurosis to provide the most external investment of the cord. The next layer, the internal spermatic fascia, is an extension of the transversalis fascia and contains the cord structures and tunica vaginalis (or an indirect hernial sac, when present).

The inferior epigastric artery, which arises from the external iliac artery and courses with its companion vein vertically in the preperitoneal fat, is the anatomic point differentiating indirect inguinal hernias from direct inguinal hernias. Hernias presenting superolateral to the inferior epigastric vessels are indirect inguinal hernias, whereas those arising inferomedial to these vessels are direct inguinal hernias.

The iliohypogastric and ilioinguinal nerves originate principally from the first lumbar nerve root and have contributions from the 12th thoracic root. The nerves traverse the transversus abdominis in the middle of the iliac crest, are deep to the internal oblique muscle until the anterior superior iliac spine, and then become superficial just beneath the external oblique aponeurosis.

The ilioinguinal nerve then runs anterior to the spermatic cord in the canal to receive sensation from the pubis and the upper scrotum (labium majus). The genital branch of the genitofemoral nerve, which arises from the first and second lumbar nerve roots, becomes superficial near the internal ring to supply motor fibers of the cremaster muscle and sensation for the scrotum and the medial aspect of the upper thigh.

The intraperitoneal view has the medial umbilical ligament as the lateral border of the bladder, and the lateral umbilical ligament helps identify the inferior epigastric vessels.

The internal inguinal ring is the apex of a triangle formed medially by the ductus deferens and laterally by the testicular vessels. The base of the triangle contains the external iliac vessels, which may be injured during laparoscopic hernia repair. The pubic tubercle, the iliopubic tract, the transversus abdominis muscular arch, the lacunar ligament, the pectineal ligament, and the lateral border of the rectus abdominis usually are easily visualized.

The obturator internus arises from the margins of the obturator foramen and the obturator membrane. The muscle fascicles exit the pelvis at the lesser sciatic foramen and have a tendinous insertion on the medial surface of the greater trochanter of the femur. The obturator vessels and nerve pass through the obturator canal, which is superior in the obturator foramen.

The obturator canal runs obliquely in the medial thigh between the pectineus, obturator externus, and adductor longus. The anterior surface of sacral vertebrae 2-4 gives rise to the piriformis to have a tendon traversing the greater sciatic foramen. Above and below this tendon, in the greater sciatic foramen, are the suprapiriform and infrapiriform foramina. The superior gluteal vessels and nerves exit through the suprapiriform foramen; the sciatic nerve, perineal nerves, and pelvic vessels pass through the infrapiriform foramen.

Pathophysiology

Inguinal hernia

The pinchcock action of the internal ring musculature during abdominal muscular straining prohibits protrusion of the intestine into a patent processus. Muscle paralysis or injury can disable the shutter effect. In addition, the transversus abdominis aponeurosis flattens during tensing, thus reinforcing the inguinal floor. A congenitally high position of the aponeurotic arch may preclude the buttressing effect. Neurapraxic or neurolytic sequelae of appendectomy or femoral vascular procedures may increase the incidence of hernia in these patients.

Clinical presentations suggest repetitive stress as a factor in hernia development. Increased intra-abdominal pressure is seen in a variety of disease states and seems to contribute to hernia formation in these populations. Elevated intra-abdominal pressure is associated with chronic cough, ascites, increased peritoneal fluid from biliary atresia, peritoneal dialysis or ventriculoperitoneal shunts, intraperitoneal masses or organomegaly, and obstipation. (See the images below.)

Ventriculoperitoneal shunt, decreased activity, and acute scrotal swelling in 6-month-old boy. Abdominal radiograph shows incarcerated shunt within communicating hydrocele. Repair of hydrocele relieved increased intracranial pressure.

Ventriculoperitoneal shunt, decreased activity, and acute scrotal swelling in 6-month-old boy. Abdominal radiograph shows incarcerated shunt within communicating hydrocele. Repair of hydrocele relieved increased intracranial pressure.

Other conditions associated with an increased incidence of inguinal hernias are exstrophy of bladder, neonatal intraventricular hemorrhage, myelomeningocele, and undescended testes. A high incidence (16-25%) of inguinal hernias occurs in premature infants; this incidence is inversely related to weight.

The rectus sheath adjacent to groin hernias is thinner than normal. The rate of fibroblast proliferation is less than normal, and the rate of collagenolysis appears increased. Sailors who developed scurvy had an increased incidence of hernia. Aberrant collagen states (eg, Ehlers-Danlos, fetal hydantoin, Freeman-Sheldon, Hunter-Hurler, Kniest, Marfan, and Morquio syndromes), have increased rates of hernia formation, as do osteogenesis imperfecta, pseudo-Hurler polydystrophy, and Scheie syndrome.

Acquired elastase deficiency also can lead to increased hernia formation. In 1981, Cannon and Read found that the increased serum elastase and decreased alpha1 -antitrypsin levels associated with smoking contribute to an increased rate of hernia in heavy smokers. The contribution of biochemical or metabolic factors to the creation of inguinal hernias remains a matter for speculation.

Inguinal hernias are commonly classified as either direct or indirect. A direct inguinal hernia usually occurs as a consequence of a defect or weakness in the transversalis fascia area of the Hesselbach triangle. The triangle is defined inferiorly by the inguinal ligament, laterally by the inferior epigastric arteries, and medially by the conjoined tendon. [4]

An indirect inguinal hernia follows the tract through the inguinal canal. It results from a persistent processus vaginalis. The inguinal canal begins in the intra-abdominal cavity at the internal ring, approximately midway between the pubic symphysis and the anterior superior iliac spine, and courses down along the inguinal ligament to the external ring, located medial to the inferior epigastric arteries, subcutaneously and slightly above the pubic tubercle. The hernia contents then follow the tract of the testicle down into the scrotal sac. [5, 6, 7]

Femoral hernia

A femoral hernia follows the tract below the inguinal ligament through the femoral canal. The canal lies medial to the femoral vein and lateral to the lacunar (Gimbernat) ligament. Because femoral hernias protrude through such a small defined space, they frequently become incarcerated or strangulated. [8] Perihernial fasciae or muscles may be malformed. [9]

Umbilical hernia

An umbilical hernia occurs through the umbilical fibromuscular ring, which is usually obliterated by age 2 years. (See the image below.) They are congenital in origin and are repaired if they persist in children older than 2-4 years. [5, 4]

Although umbilical hernias in children arise from failed closure of the umbilical ring, only one in 10 adults with umbilical hernias had this defect as a child. Adult umbilical hernias occur through a canal bordered anteriorly by the linea alba, posteriorly by the umbilical fascia, and laterally by the rectus sheath. Proof that umbilical hernias persist from childhood to present in adulthood is only hinted at by an increased incidence among black Americans. Multiparity, increased abdominal pressure, and a single midline decussation are associated with umbilical hernias.

Congenital hypothyroidism, fetal hydantoin syndrome, Freeman-Sheldon syndrome, Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome, and disorders of collagen and polysaccharide metabolism (such as Hunter-Hurler syndrome, osteogenesis imperfecta, and Ehlers-Danlos syndrome), should be considered as possibilities in children with large umbilical hernias.

Richter hernia

A Richter hernia occurs when only the antimesenteric border of the bowel herniates through the fascial defect. This hernia involves only a portion of the circumference of the bowel. Thus, the bowel may not be obstructed, even if the hernia is incarcerated or strangulated, and the patient may not present with vomiting. A Richter hernia can occur with any of the abdominal hernias and is particularly dangerous in that a portion of strangulated bowel may inadvertently be reduced into the abdominal cavity, leading to perforation and peritonitis. [10]

Incisional hernia

An incisional hernia is an iatrogenic condition that occurs in 2-10% of all abdominal operations secondary to breakdown of the fascial closure of a surgical procedure. (See Guidelines.) Even after repair, recurrence rates approach 20-45%.

Spigelian hernia

A spigelian hernia occurs through a defect in the spigelian fascia, defined by the lateral edge of the rectus abdominis at the semilunar line (from costal arch to pubic tubercle). Abnormal orientation of the semilunar and semicircular lines, along with obesity, increased intra-abdominal pressure, aging, and rapid weight loss, leads to the production of spigelian hernias.

There are two subtypes of spigelian hernia, interstitial and subcutaneous. Distinguishing between these subtypes helps optimize the surgical approach (when indicated) and is best done by means of computed tomography (CT). [11, 12, 13]

Obturator hernia

An obturator hernia passes through the obturator foramen, following the path of the obturator nerves and muscles. There is a strong female preponderance (female-to-male ratio, 6:1), because of a gender-specific larger canal diameter; this hernia is also much more likely to occur in the elderly. Because of its anatomic position, an obturator hernia more commonly presents as a bowel obstruction than as a protrusion of bowel contents. [14, 10]

Other hernias

Aberrant formation of the decussations of the linea alba, leading to a midline pattern of single anterior and posterior lines, predisposes to the formation of epigastric hernias (epiploceles). Internal supravesical hernias probably arise from a congenital fascial deficiency. Perihernial fasciae or muscles may be malformed in lumbar hernias. Interparietal hernias are often a product of ectopic testicular descent. Multiparity and age produce laxity of the pelvic floor to cause perineal hernias.

Congenital abdominal wall defects

The underlying embryogenic factor in omphalocele and gastroschisis is deficient closure of the developing anterior wall at the umbilical stalk. Variations in lateral fold migration can result in both of these defects. [15] In addition, most children with omphalocele and all children with gastroschisis have intestinal malrotation; their extracoelomic location precludes normal attachment of the intestines to the posterior peritoneum.

Improper development of other portions of the abdominal wall leads to specific anomalies. In 1967, Duhamel proposed that maldevelopment of the superior (cephalad) fold of the abdominal wall leads to the thoracic, sternal and diaphragmatic, and abdominal wall defects that make up the upper midline syndrome (pentalogy of Cantrell). This syndrome includes a bifid sternal cleft, an anterior diaphragmatic defect, an anterior pericardial defect, an epigastric omphalocele, and congenital cardiac defects.

Maldevelopment of the inferior (caudal) fold produces pelvic, hindgut, sacral, genital, and bladder defects. Lower midline syndrome includes a hypogastric omphalocele, exstrophy of the bladder or cloaca, vesicointestinal fissure, colonic atresia, imperforate anus, sacral vertebral defects, and often meningoceles.

Lateral fold maldevelopment results in omphalocele (see the image below), as well as gastroschisis. It has been postulated that an omphalocele results from persistence of the umbilical stalk in the somatopleure. Approximately 20% of infants with omphaloceles have an associated chromosomal abnormality (eg, trisomy 13, trisomy 18, trisomy 21, or Klinefelter syndrome).

An omphalocele-exstrophy-imperforate anus-spinal defects (OEIS) complex is characterized by a combination of omphalocele, exstrophy of the bladder, an imperforate anus, and spinal defects. [16] More than 50% of infants with omphaloceles have associated neurologic, urinary tract, cardiac, and skeletal anomalies. The liver is present in the omphalocele sac in 35% of patients. In small omphaloceles, there is a high coincidence of Meckel diverticulum.

Maternal smoking is associated with an increased prevalence of omphalocele and gastroschisis. An increased incidence of abdominal wall defects is related to surface water atrazine and nitrate levels. [17]

Gastroschisis is thought to be the result of a failure of the umbilical coelom to develop to an appropriate size. The intestine then ruptures out of the body wall to the right of the umbilicus, where a slight weakness exists secondary to resorption of the right umbilical vein early in gestation (see the image below). Gastroschisis is associated with intestinal atresias in 10-15% of cases, probably as a consequence of interruption of the vascular supply to the intestine.

Experimentally, administration of the insecticide methylparathion has produced gastroschisis. Transplacental transmission of such teratogens helps explain gastroschisis in siblings with different fathers.

Etiology

The etiology of indirect hernias is largely explainable in terms of the embryology of the groin and of testicular descent. An indirect inguinal hernia is a congenital hernia, regardless of the patient’s age. It occurs because of protrusion of an abdominal viscus into an open processus vaginalis. The following terms are employed:

-

If the processus contains viscera, the patient has an indirect inguinal hernia

-

If peritoneal fluid fluxes between the space and the peritoneum, the patient has a communicating hydrocele

-

If fluid accumulates in the scrotum or spermatic cord without exchange of fluid with the peritoneum, the patient has a noncommunicating scrotal hydrocele or a hydrocele of the cord; in a girl, fluid accumulation in the processus results in a hydrocele of the canal of Nuck

The inguinal canal forms by mesenchyme condensation around the gubernaculum. During the first trimester, the gubernaculum extends from the testis to the labioscrotal fold, and the processus vaginalis and its fascial coverings form. A bilateral oblique defect in the abdominal wall develops during week 6 or 7 of gestation as the muscular wall develops around the gubernaculum. The processus vaginalis protrudes from the peritoneal cavity and lies anteriorly, laterally, and medially to the gubernaculum by week 8 of gestation.

Beginning at week 8 of gestation, the testis produces many male hormones. At the beginning of month 7, the gubernaculum begins a marked swelling influenced by a nonandrogenic hormone, probably a müllerian inhibiting substance. This results in expansion of the inguinal canal and the labioscrotal fold, forming the scrotum. The genitofemoral nerve also influences migration of the testis and gubernaculum into the scrotum under androgenic control.

The female inguinal canal and processus are much less developed than their male equivalents. The inferior aspect of the gubernaculum is converted to the round ligament. The cephalad part of the female gubernaculum becomes the ovarian ligament.

Gonads develop on the medial aspect of the mesonephros during week 5 of gestation. The kidney then moves cephalad, leaving the gonad to reside in the pelvis until month 7 of gestation. During this time, it retains a ligamentous attachment to the proximal gubernaculum.

The gonads then migrate along the processus vaginalis, with the ovary descending into the pelvis and the testis being wrapped within the distal processus (tunica vaginalis). The processus fails to close adequately at birth in 40-50% of boys. Therefore, other factors play a role in the development of a clinical indirect hernia. A familial tendency exists, with 11.5% of patients having a family history. The relative risk of inguinal hernia is 5.8 for brothers of male cases, 4.3 for brothers of female cases, 3.7 for sisters of male cases, and 17.8 for sisters of female cases.

More generally, any condition that increases the pressure in the intra-abdominal cavity may contribute to the formation of a hernia, including the following:

-

Marked obesity

-

Heavy lifting

-

Coughing

-

Straining with defecation or urination

-

Ascites

-

Peritoneal dialysis

-

Ventriculoperitoneal shunt

-

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)

-

Family history of hernias [18]

Epidemiology

United States statistics

As much as 10% of the population develops some type of hernia during life. [19] More than 1 million abdominal hernia repairs are performed each year, with inguinal hernia repairs constituting nearly 770,000 of these cases. [1, 2, 3] Frequencies of various types of hernias are as follows:

-

Approximately 75% of all hernias are inguinal; of these, 50% are indirect (male-to-female ratio, 7:1), with a right-side predominance, and 25% are direct [5] ; 3% of inguinal hernias have a sliding component, most often on the left side (left-to-right ratio, 4.5:1)

-

About 14% of hernias are umbilical

-

About 10% of hernias are incisional or ventral (female-to-male ratio, 2:1) [7]

-

Only 3-5% of hernias are femoral

-

Interparietal, supravesical, lumbar, sciatic, and perineal hernias are rare; interparietal hernias are on the right side in 70% of cases, and a similar percentage of cases involve testicular maldescent (Denis-Browne pouch)

In the case of congenital abdominal wall defects, the incidence of omphalocele has increased only slightly over the past few decades, to a current level of about 1-2.5 in 5000 live births. In contrast, the incidence of gastroschisis has increased markedly over the past 25 years, to a current level of 1 in 3600 live births. In some areas, the prevalence of gastroschisis has increased by as much as 400% over the past two decades.

International statistics

Data from developing countries are limited. Consequently, accurate determinations of incidence and prevalence are unavailable. Current epidemiologic assessments suggest that gender distribution and anatomic distribution are similar to those in more developed countries.

Age-related demographics

The prevalence of all varieties of hernias increases with age.

The incidence of inguinal hernias in children is as high as 4.5%. Indirect hernias usually present during the first year of life, but they may not appear until middle or old age. Indirect hernias are more common in premature infants than in term infants; they develop in 13% of infants born before 32 weeks’ gestation. [2] Direct hernias occur in older patients as a result of relaxation of abdominal wall musculature and thinning of the fascia.

Umbilical hernias occur in approximately one of every six children. [2, 5] They usually develop in infants and reach their maximal size by the first month of life. Most hernias of this type close spontaneously by the first year of life; the incidence in children older than 1 year is only 2-10%. [20]

Spigelian hernias are rare and typically occur around the age of 50 years; no sex or side predilection is reported. Primary perineal hernias occur most often in elderly multiparous women. Obturator hernias occur most often in thin, elderly women and are more common on the right side. Richter hernias present late in life, most often in women with femoral hernias. Littre hernias have a much broader spectrum of hernia site and occur across all ages.

The incidence of incarcerated or strangulated hernias in pediatric patients is 10-20%; 50% of these occur in infants younger than 6 months. [2]

Sex-related demographics

Inguinal hernias are the most common type in both males and females; approximately 25% of males and 2% of females have an inguinal hernia over the course of their lifetime. [3, 21] The male-to-female ratio for indirect inguinal hernia is 7:1.

Sliding hernias are much more common in men than in women, and the predominance increases with age. Female infants have a high incidence of sliding tube, ovary, or broad ligament hernias.

Femoral hernias (though rare overall) occur more frequently in women because of the differences in the pelvic anatomy (female-to-male ratio, 1.8:1). Umbilical hernias are equally common in male and female children but are 3 times more frequent in female adults than in male adults (overall female-to-male ratio, 1.7:1). Incisional or ventral hernias are also more common in females (female-to-male ratio, 2:1), as are obturator hernias (female-to-male ratio, 6:1). [21]

Epigastric hernias have a prevalence of 0.5% and are more common in males (male-to-female ratio, 3:1). Reports of internal supravesical hernias are limited, but the literature suggests that they occur more often in men and in elderly people.

Race-related demographics

Umbilical hernias are much more common in persons of African ethnicity. [22] With respect to the pediatric population, umbilical hernias occur eight times more frequently in black infants than in white infants. [21]

Prognosis

The prognosis depends on the type and size of hernia, as well as on the ability to reduce risk factors associated with the development of hernias. As a rule, the prognosis is good with timely diagnosis and repair. Morbidity typically is secondary either to missing the diagnosis of the hernia or to complications associated with management of the disease.

A hernia can lead to an incarcerated and often obstructed bowel, or even to a strangulated bowel with a compromised blood supply, which, if missed, can result in bowel perforation and peritonitis. Reduction of the strangulated bowel leads to persistent ischemia or necrosis with no clinical improvement. Surgical intervention is required to prevent further complications (eg, perforation and sepsis.

In general, patients with uncomplicated inguinal and abdominal wall hernias do well. However, mortality is 10% for those who have hernias with associated strangulation. It should be kept in mind that surgery to repair the hernia or manage its complications may leave the patient at risk for infection or intra-abdominal adhesions. In addition, hernias can reappear in the same location, even after surgical repair.

In a study investigating complications during and after 780 laparoscopic inguinal herniorrhaphies in 569 patients, Coelho et al found that hernias recurred in 14 patients (2.5%) and that intraoperative complications occurred in 28 (4.9%), with extensive subcutaneous emphysema being the most common complication. [23]

Postoperative complications developed in 35 patients (6.2%). Small bowel perforation occurred in one patient, and bladder perforation occurred in another. [23] One cohort member developed an extensive, preperitoneal Mycobacterium massiliense infection. No cohort members died. The authors concluded that despite having a low mortality, laparoscopic inguinal herniorrhaphy can result in life-threatening complications.

Inguinal hernia

Potential complications of inguinal hernia repair include the following:

-

Hernia recurrence

-

Infarcted testis or ovary with subsequent atrophy (see the images below)

-

Wound infection

-

Bladder injury

-

Iatrogenic orchiectomy or vasectomy

-

Intestinal injury

Testis at operation in 2-month-old boy with history of irritability and vomiting for 36 hours. Capsulotomy was performed, but atrophy occurred. Patient also required bowel resection.

Testis at operation in 2-month-old boy with history of irritability and vomiting for 36 hours. Capsulotomy was performed, but atrophy occurred. Patient also required bowel resection.

Postoperative death is usually related either to complications (eg, strangulated bowel) or to preexisting risk factors. [24] A postoperative hydrocele results from fluid accumulation in the distal sac. This usually resolves spontaneously but sometimes must be aspirated.

A femoral hernia as a sequela of inguinal hernia repair may have been overlooked initially. Unilateral transection of the vas deferens can cause infertility through antibody production. Iatrogenic cryptorchidism can occur in children (1.3%) if the testicle is not placed in the scrotum at the end of the operation; orchiopexy is required for correction. Iliohypogastric and ilioinguinal neuralgia may develop but usually will regress within months; in refractory cases, nerve blocks or neurectomy may be employed.

Most recurrences develop within 5 years after the operation. They are often associated with incarcerated hernias, concurrent orchiopexy, sliding hernias (in girls), or emergency operations. The recurrence rate is higher in children younger than 1 year and in the elderly. It is also higher in patients with ongoing increased intra-abdominal pressure, growth failure and malnutrition, prematurity, seizure disorder, or chronic respiratory problems.

Technical factors that increase the likelihood of recurrence include the following:

-

Unrecognized tear in the sac

-

Failure to repair a large internal inguinal ring

-

Damage to the floor of the inguinal canal

-

Infection or other postoperative complications

In some cases, a direct hernia may result from vigorous dissection; in others, it may be a simultaneous hernia that was initially unrecognized.

Other hernia types

Recurrence, bleeding, infection, and persisting pain are potential complications for the other types of abdominal wall hernia. The rate of recurrence for incisional hernias may be as high as 30%. The addition of mesh to most abdominal wall hernia repairs is decreasing the incidence of recurrence.

Gastroschisis and omphalocele

Infants with uncomplicated gastroschisis and omphalocele generally fare well, with a mortality of less than 5%. [25] Complications arising from the prolonged time required to reduce the contents into the abdomen include the following:

-

Infection

-

Dislodgment of the prosthesis

-

Prolonged mechanical ventilation

-

Intestinal obstruction

-

Budd-Chiari syndrome (due to kinking of the suprahepatic inferior vena cava)

However, mortality among infants with gastroschisis or omphalocele who have intestinal atresia or severe associated anomalies is substantially higher, in the range of 15-50%.

Intestinal atresias occur in about 20% of infants with gastroschisis. Massive atresias present infrequently with their attendant sequela of short gut syndrome. Maximal bowel preservation, achieved by means of “second-look” operations 24-48 hours after initial management, may be warranted. Infants with gastroschisis are at risk for necrotizing enterocolitis after the initiation of feeding. This is managed by bowel rest and broad-spectrum antibiotics; surgery is seldom necessary.

An increased incidence of gastroesophageal reflux after closure of gastroschisis and omphalocele often necessitates the administration of antireflux medication. Severe reflux and hiatal hernias require operative correction. Adhesive small bowel obstruction is a frequent occurrence in the first year following treatment of congenital abdominal wall defects, with previous sepsis and fascial dehiscence as predictive factors. [26]

Long-term follow-up shows function equal to that reported in age-related groups.

Patient Education

Patients should be counseled to avoid those activities that increase intra-abdominal pressure (eg, straining at defecation and lifting heavy objects). This may require restrictions on work or school-related activities, which should be clearly delineated. Patients should also receive instruction regarding ways of applying support to the hernia. Numerous medical device companies have developed support items that can assist with this process.

Even with asymptomatic hernias, repair at an early stage (ie, before the hernia enlarges) is preferred. Referral to a general surgeon for discussion of the available types of hernia repair is warranted; with the advent of new meshes and laparoscopic approaches, the range of repair options is now wider than ever.

-

Large right inguinal hernia in 3-month-old girl.

-

In this baby with gastroschisis, bowel is uncovered and presents to right inferior aspect of cord.

-

Hernia of umbilical cord.

-

Note translucent sac in baby with large omphalocele. Umbilical vessels attach to sac.

-

Hernia content balloons over external ring when reduction is attempted.

-

Hernia can be reduced by medial pressure applied first.

-

Infant with Silon chimney placed in treatment of gastroschisis.

-

Atrophy of right testis after hernia repair. Note adult-type incision.

-

Iatrogenic cryptorchid testis in child. Taking care to position testis in scrotum is integral part of completion of hernia repair in boys.

-

Erythematous edematous left scrotum in 2-month-old boy with history of irritability and vomiting for 36 hours. Local signs of this magnitude preclude reduction attempts.

-

Testis at operation in 2-month-old boy with history of irritability and vomiting for 36 hours. Capsulotomy was performed, but atrophy occurred. Patient also required bowel resection.

-

Ventriculoperitoneal shunt, decreased activity, and acute scrotal swelling in 6-month-old boy.

-

Ventriculoperitoneal shunt, decreased activity, and acute scrotal swelling in 6-month-old boy. Abdominal radiograph shows incarcerated shunt within communicating hydrocele. Repair of hydrocele relieved increased intracranial pressure.

-

Bassini-type repair approximating transversus abdominis aponeurosis and transversalis fascia to iliopubic tract and inguinal ligament.

-

Anatomic locations for various hernias.