Practice Essentials

Meningitis is a clinical syndrome characterized by inflammation of the meninges. [1, 2]

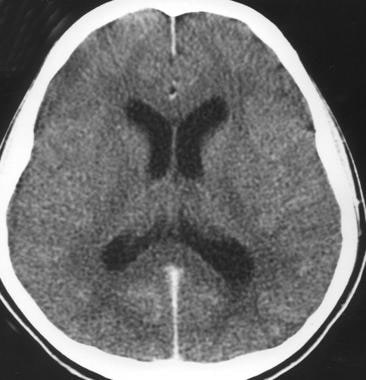

Acute bacterial meningitis. This axial nonenhanced computed tomography scan shows mild ventriculomegaly and sulcal effacement.

Acute bacterial meningitis. This axial nonenhanced computed tomography scan shows mild ventriculomegaly and sulcal effacement.

Signs and symptoms

The classic triad of bacterial meningitis consists of the following [1, 2] :

-

Fever

-

Headache

-

Neck stiffness

Up to 95% of patients with bacterial meningitis have at least 2 of the 4 following symptoms: fever, headache, stiff neck, or altered mental status. [2]

Other symptoms can include nausea, vomiting, photalgia (photophobia), sleepiness, confusion, irritability, delirium, and coma. Patients with viral meningitis may have a history of preceding systemic symptoms (eg, myalgias, fatigue, or anorexia).

The history should address the following:

-

Epidemiologic factors and predisposing risks such as mosquito bites ( West Nile virus in endemic months, June-October in the United States)

-

Exposure to a sick contact (small children with febrile illness)

-

Previous medical treatment and existing conditions

-

Geographic location and travel history

-

Season and temperature ( enterovirus and West Nile virus in the summer and fall; herpes simplex virus type 2 year round)

Acute bacterial meningitis in otherwise healthy patients who are not at the extremes of age presents in a clinically obvious fashion; however, subacute bacterial meningitis often poses a diagnostic challenge.

General physical findings in viral meningitis are common to all causative agents. Enteroviral infection is suggested by the following:

-

Exanthemas

-

Contact with small children with febrile illnesses

-

Symptoms of pericarditis, myocarditis, or conjunctivitis [1]

-

Syndromes of pleurodynia, herpangina, and hand-foot-and-mouth disease

See Acute Pericarditis, Myocarditis, Viral Conjunctivitis, Pleurodynia, Herpangina, and Hand-foot-and-mouth Disease.

Infants may have the following:

-

Bulging fontanelle (if euvolemic)

-

Paradoxic irritability (ie, remaining quiet when stationary and crying when held)

-

High-pitched cry

-

Hypotonia

The examination should evaluate the following:

-

Focal neurologic signs

-

Signs of meningeal irritation

-

Systemic and extracranial findings

-

Level of consciousness

In chronic meningitis, it is essential to perform careful general, systemic, and neurologic examinations, looking especially for the following:

-

Lymphadenopathy

-

Papilledema

-

Meningismus

-

Cranial nerve palsies

-

Other focal neurologic signs

Patients with aseptic meningitis syndrome usually appear clinically nontoxic, with no vascular instability. They characteristically have an acute onset of meningeal symptoms, fever, and CSF pleocytosis that is usually prominently lymphocytic.

See Clinical Presentation for more detail.

Diagnosis

The diagnostic challenges in patients with clinical findings of meningitis are as follows:

-

Early identification and treatment of patients with acute bacterial meningitis

-

Assessing whether a treatable CNS infection is present in those with suspected subacute or chronic meningitis

-

Identifying the causative organism

Blood studies that may be useful include the following:

-

Complete blood count (CBC) with differential

-

Serum electrolytes

-

Serum glucose (which is compared with the CSF glucose)

-

Blood urea nitrogen (BUN) or creatinine and liver profile

In addition, the following tests may be ordered [1, 2] :

-

Blood, nasopharynx, respiratory secretion, urine or skin lesion cultures or antigen/polymerase chain reaction (PCR) detection assays

-

Syphilis testing

-

Serum procalcitonin testing

-

Lumbar puncture and CSF analysis

-

Neuroimaging (CT of the head or MRI of the brain)

See Workup for more detail.

Management

Initial measures include the following:

-

Shock or hypotension – Crystalloids

-

Altered mental status – Seizure precautions and treatment (if necessary), along with airway protection (if warranted)

-

Stable with normal vital signs – Oxygen, IV access, and rapid transport to the emergency department (ED)

Treatment of bacterial meningitis includes the following:

-

Prompt initiation of empiric antibacterial therapy as appropriate for patient age and condition

-

After identification of the pathogen and determination of susceptibilities, targeted antibiotic therapy as appropriate for patient age and condition

-

Steroid (typically, dexamethasone) therapy

-

In certain patients, consideration of intrathecal antibiotics

The following systemic complications of acute bacterial meningitis must be treated:

-

Hypotension or shock

-

Hypoxemia

-

Hyponatremia

-

Cardiac arrhythmias and ischemia

-

Stroke

-

Exacerbation of chronic diseases

Most cases of viral meningitis are benign and self-limited, but in certain instances, specific antiviral therapy may be indicated, if available.

Other types of meningitis are treated with specific therapy as appropriate for the causative pathogen, as follows:

-

Fungal meningitis - Cryptococcal (amphotericin B, flucytosine, fluconazole), Coccidioides immitis (fluconazole, amphotericin B, itraconazole), Histoplasma capsulatum (liposomal amphotericin B, itraconazole), or Candida (amphotericin plus 5-flucytosine)

-

Tuberculous meningitis (isoniazid, rifampin, pyrazinamide, ethambutol, streptomycin)

-

Parasitic meningitis (amebic [Naegleria fowleri] or acanthamebic) - Variable regimens

-

Lyme meningitis (ceftriaxone; alternatively, penicillin G, doxycycline, chloramphenicol)

See Treatment and Medication for more detail.

Background

Infections of the central nervous system (CNS) can be divided into 2 broad categories: those primarily involving the meninges (meningitis; see the image below) and those primarily confined to the parenchyma (encephalitis).

The 3 layers of membranes that enclose the brain and spinal cord.

-

Dura mater - A tough outer membrane

-

Arachnoid mater - A lacy, weblike middle membrane

-

Pia mater – Is firmly attached to spinal cord and has rich blood supply

-

Subarachnoid space - A delicate, fibrous inner layer that contains many of the blood vessels that feed the brain and spinal cord and is between arachnoid mater and pia mater

Arachnoid and pia mater are called leptomeninges

Meningitis is inflammation of leptomeninges including subarachnoid space leading to a constellation of signs and symptoms and presence of inflammatory cells in CSF.

Pachymeningitis is inflammation of dura mater that usually is manifested by thickening of the intracranial dura mater on radiology

Other definitions

-

Acute meningitis is defined as onset of symptoms of meningeal inflammation over the course of hours to several days

-

Chronic meningitis is defined as at least 4 weeks of symptoms of inflammation of meninges

-

Aseptic meningitis refers to a syndrome consistent with signs and symptoms of meningeal inflammation but with negative routine CSF cultures

-

Recurrent meningitis is defined as at least 2 episodes of signs and symptoms of meningeal inflammation with associated CSF findings separated by a period of full recovery.

Pathophysiology

Most cases of meningitis are caused by an infectious agent that has colonized or established a localized infection elsewhere in the host. Potential sites of colonization or infection include the skin, the nasopharynx, the respiratory tract, [3, 4] the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, and the genitourinary tract. The organism invades the submucosa at these sites by circumventing host defenses (eg, physical barriers, local immunity, and phagocytes or macrophages).

An infectious agent (ie, a bacterium, virus, fungus, or parasite) can gain access to the CNS and cause meningeal disease via any of the 3 following major pathways:

-

Invasion of the bloodstream (ie, bacteremia, viremia, fungemia, or parasitemia) and subsequent hematogenous seeding of the CNS

-

A retrograde neuronal (eg, olfactory and peripheral nerves) pathway (eg, Naegleria fowleri or Gnathostoma spinigerum)

-

Direct contiguous spread (eg, sinusitis, otitis media, congenital malformations, trauma, or direct inoculation during intracranial manipulation)

Invasion of the bloodstream and subsequent seeding is the most common mode of spread for most agents. This pathway is characteristic of meningococcal, cryptococcal, syphilitic, and pneumococcal meningitis.

Rarely, meningitis arises from invasion via septic thrombi or osteomyelitic erosion from infected contiguous structures. Meningeal seeding also may occur with a direct bacterial inoculate during trauma, neurosurgery, or instrumentation. Meningitis in the newborn may be transmitted vertically, involving pathogens that have colonized the maternal intestinal or genital tract, or horizontally, from nursery personnel or caregivers at home.

Local extension from contiguous extracerebral infection (eg, otitis media, mastoiditis, or sinusitis) is a common cause. Possible pathways for the migration of pathogens from the middle ear to the meninges include the following:

-

The bloodstream

-

Preformed tissue planes (eg, posterior fossa)

-

Temporal bone fractures

-

The oval or round window membranes of the labyrinths

The brain is naturally protected from the body’s immune system by the barrier that the meninges create between the bloodstream and the brain. Normally, this protection is an advantage because the barrier prevents the immune system from attacking the brain. However, in meningitis, the blood-brain barrier can become disrupted; once bacteria or other organisms have found their way to the brain, they are somewhat isolated from the immune system and can spread.

When the body tries to fight the infection, the problem can worsen; blood vessels become leaky and allow fluid, WBCs, and other infection-fighting particles to enter the meninges and brain. This process, in turn, causes brain swelling and can eventually result in decreasing blood flow to parts of the brain, worsening the symptoms of infection. [5]

Depending on the severity of bacterial meningitis, the inflammatory process may remain confined to the subarachnoid space. In less severe forms, the pial barrier is not penetrated, and the underlying parenchyma remains intact. However, in more severe forms of bacterial meningitis, the pial barrier is breached, and the underlying parenchyma is invaded by the inflammatory process. Thus, bacterial meningitis may lead to widespread cortical destruction, particularly when left untreated.

Replicating bacteria, increasing numbers of inflammatory cells, cytokine-induced disruptions in membrane transport, and increased vascular and membrane permeability perpetuate the infectious process in bacterial meningitis. These processes account for the characteristic changes in CSF cell count, pH, lactate, protein, and glucose in patients with this disease.

Exudates extend throughout the CSF, particularly to the basal cisterns, resulting in the following:

-

Damage to cranial nerves (eg, cranial nerve VIII, with resultant hearing loss)

-

Obliteration of CSF pathways (causing obstructive hydrocephalus)

-

Induction of vasculitis and thrombophlebitis (causing local brain ischemia)

Intracranial pressure and cerebral fluid

One complication of meningitis is the development of increased intracranial pressure (ICP). The pathophysiology of this complication is complex and may involve many proinflammatory molecules as well as mechanical elements. Interstitial edema (secondary to obstruction of CSF flow, as in hydrocephalus), cytotoxic edema (swelling of cellular elements of the brain through the release of toxic factors from the bacteria and neutrophils), and vasogenic edema (increased blood brain barrier permeability) all are thought to play a role.

Without medical intervention, the cycle of decreasing CSF, worsening cerebral edema, and increasing ICP proceeds unchecked. Ongoing endothelial injury may result in vasospasm and thrombosis, further compromising CSF, and may lead to stenosis of large and small vessels. Systemic hypotension (septic shock) also may impair CSF, and the patient soon dies as a consequence of systemic complications or diffuse CNS ischemic injury.

Cerebral edema

The increased CSF viscosity resulting from the influx of plasma components into the subarachnoid space and diminished venous outflow lead to interstitial edema. The accumulation of the products of bacterial degradation, neutrophils, and other cellular activation leads to cytotoxic edema.

The ensuing cerebral edema (ie, vasogenic, cytotoxic, and interstitial) significantly contributes to intracranial hypertension and a consequent decrease in cerebral blood flow. Anaerobic metabolism ensues, which contributes to increased lactate concentration and hypoglycorrhachia. In addition, hypoglycorrhachia results from decreased glucose transport into the spinal fluid compartment. Eventually, if this uncontrolled process is not modulated by effective treatment, transient neuronal dysfunction or permanent neuronal injury results.

Cytokines and secondary mediators in bacterial meningitis

Key advances in understanding the pathophysiology of meningitis include insight into the pivotal roles of cytokines (eg, tumor necrosis factor alpha [TNF-α] and interleukin [IL]-1), chemokines (IL-8), and other proinflammatory molecules in the pathogenesis of pleocytosis and neuronal damage during occurrences of bacterial meningitis.

Increased CSF concentrations of TNF-α, IL-1, IL-6, and IL-8 are characteristic findings in patients with bacterial meningitis. Cytokine levels, including those of IL-6, TNF-α, and interferon gamma, are elevated in patients with aseptic meningitis.

The proposed events involving these inflammation mediators in bacterial meningitis begin with the exposure of cells (eg, endothelial cells, leukocytes, microglia, astrocytes, and meningeal macrophages) to bacterial products released during replication and death; this exposure incites the synthesis of cytokines and proinflammatory mediators. This process likely is initiated by the ligation of the bacterial components (eg, peptidoglycan and lipopolysaccharide) to pattern-recognition receptors, such as the Toll-like receptors (TLRs).

TNF-α and IL-1 are most prominent among the cytokines that mediate this inflammatory cascade. TNF-α is a glycoprotein derived from activated monocyte-macrophages, lymphocytes, astrocytes, and microglial cells.

IL-1, previously known as endogenous pyrogen, also is produced primarily by activated mononuclear phagocytes and is responsible for the induction of fever during bacterial infections. Both IL-1 and TNF-α have been detected in the CSF of individuals with bacterial meningitis. In experimental models of meningitis, they appear early during the course of disease and have been detected within 30 to 45 minutes of intracisternal endotoxin inoculation.

Many secondary mediators, such as IL-6, IL-8, nitric oxide, prostaglandins (eg, prostaglandin E2 [PGE2]), and platelet activation factor (PAF), are presumed to amplify this inflammatory event, either synergistically or independently. IL-6 induces acute-phase reactants in response to bacterial infection. The chemokine IL-8 mediates neutrophil chemoattractant responses induced by TNF-α and IL-1.

Nitric oxide is a free radical molecule that can induce cytotoxicity when produced in high amounts. PGE2, a product of cyclooxygenase (COX), appears to participate in the induction of increased blood-brain barrier permeability. PAF, with its myriad biologic activities, is believed to mediate the formation of thrombi and the activation of clotting factors within the vasculature. However, the precise roles of all these secondary mediators in meningeal inflammation remain unclear.

The net result of the above processes is vascular endothelial injury and increased blood-brain barrier permeability, leading to the entry of many blood components into the subarachnoid space. In many cases, this contributes to vasogenic edema and elevated CSF protein levels. In response to the cytokines and chemotactic molecules, neutrophils migrate from the bloodstream and penetrate the damaged blood-brain barrier, producing the profound neutrophilic pleocytosis characteristic of bacterial meningitis.

Genetic predisposition to inflammatory response

The inflammatory response and the release of proinflammatory mediators are critical to the recruitment of excess neutrophils to the subarachnoid space. These activated neutrophils release cytotoxic agents, including oxidants and metalloproteins that cause collateral damage to brain tissue.

Pattern recognition receptors, of which TLR A4 (TLRA4) is the best studied, lead to increase in the myeloid differentiation 88 (MyD88)-dependent pathway and excess production of proinflammatory mediators. At present, dexamethasone is used to decrease the effects of cellular toxicity by neutrophils after they are present. Researchers are actively seeking ways to inhibit TLRA4 and other proinflammatory recognition receptors through genetically engineered suppressors. [6]

Etiology

Acute Bacterial Meningitis

Bacterial meningitis consists of pyogenic inflammation of the meninges and the underlying subarachnoid CSF, with a bacterial cause of this syndrome. This usually is characterized by an acute onset of meningeal symptoms and neutrophilic pleocytosis. If not treated, it may lead to lifelong disability or death. [2, 7, 8] Depending on age and general condition, patients with acute bacterial meningitis present acutely with signs and symptoms of meningeal inflammation and systemic infection of less than 24 hours’ (and usually >12 hours’) duration.

Bacterial seeding of the meninges usually occurs through hematogenous spread. In patients without an identifiable source of infection, local tissue and bloodstream invasion by bacteria that have colonized the nasopharynx may be a common source. Many meningitis-causing bacteria are carried in the nose and throat, often asymptomatically. Most meningeal pathogens are transmitted through the respiratory route, including Neisseria meningitidis (meningococcus) and S pneumoniae (pneumococcus).

Certain respiratory viruses are thought to enhance the entry of bacterial agents into the intravascular compartment, presumably by damaging mucosal defenses. Once in the bloodstream, the infectious agent must escape immune surveillance (eg, antibodies, complement-mediated bacterial killing, and neutrophil phagocytosis).

Subsequently, hematogenous seeding into distant sites, including the CNS, occurs. The specific pathophysiologic mechanisms by which the infectious agents gain access to the subarachnoid space remain unclear. Once inside the CNS, the infectious agents likely survive because host defenses (eg, immunoglobulins, neutrophils, and complement components) appear to be limited in this body compartment. The presence and replication of infectious agents remain uncontrolled and incite the cascade of meningeal inflammation described above.

With almost 4100 cases and 500 deaths occurring annually in the United States, bacterial meningitis continues to be a significant source of morbidity and mortality. The annual incidence in the United States is 1.33 cases per 100,000 population. [7]

The specific infectious agents that are involved in bacterial meningitis vary among different patient age groups, and the meningeal inflammation may evolve into the following conditions:

-

Ventriculitis

-

Empyema

-

Cerebritis

-

Abscess formation

Some of the bacteria associated with bacterial meningitis include the following [2] :

Streptococcus pneumoniae

Staphylococcus aureus

Coagulase negative Staphylococcus

Streptococcus pyogenes

Streptococcus agalactiae

Viridans streptococci

Enterococcus spp

Haemophilus influenzae

Listeria monocytogens

Cutibacterium acnes

Escherichia coli

Klebsiella pneumoniae

Pseudomonas aeruginosa

Salmonella spp

Acinetobacter spp

Stenotrophomonas maltophilia

Fusobacterium necrophorum

Pasteurella multocida

Capnocytophaga canimorsus

Table 1. Most Common Bacterial Pathogens on Basis of Age and Predisposing Risks (Open Table in a new window)

Risk or Predisposing Factor |

Bacterial Pathogen |

Age 0-4 weeks |

Streptococcus agalactiae (GBS) Escherichia coli K1 Listeria monocytogenes |

Age 4-12 weeks |

S agalactiae E coli Haemophilus influenzae Streptococcus pneumoniae Neisseria meningitidis |

Age 3 months to 18 years |

N meningitidis S pneumoniae H influenzae |

Age 18-50 years |

S pneumoniae N meningitidis H influenzae |

Age >50 years |

S pneumoniae N meningitidis L monocytogenes Aerobic gram-negative bacilli |

Immunocompromised state |

S pneumoniae N meningitidis L monocytogenes Aerobic gram-negative bacilli |

Intracranial manipulation, including neurosurgery |

Staphylococcus aureus Coagulase-negative staphylococci Aerobic gram-negative bacilli, including Pseudomonas aeruginosa |

Basilar skull fracture |

S pneumoniae H influenzae Group A streptococci |

CSF shunts |

Coagulase-negative staphylococci S aureus Aerobic gram-negative bacilli Propionibacterium acnes |

CSF = cerebrospinal fluid; GBS = group B streptococcus. |

|

Some of the more common bacterial pathogens causing meningitis are elaborated below, but any bacteria is capable of causing meningitis

H influenzae meningitis

H influenzae is a small, pleomorphic, gram-negative coccobacillus that is frequently found as part of the normal flora in the upper respiratory tract. The organism can spread from one individual to another in airborne droplets or by direct contact with secretions. Meningitis is the most serious acute manifestation of systemic infection with H influenzae.

In the past, H influenzae was a major cause of meningitis, and the encapsulated type b strain of the organism (Hib) accounted for the majority of cases. Since the introduction of Hib vaccine in the United States in 1990, the overall incidence of H influenzae meningitis has decreased by 35%, with Hib accounting for fewer than 9.4% of H influenzae cases. [2, 7]

The isolation of H influenzae in adults suggests the presence of an underlying medical disorder, such as the following:

-

Paranasal sinusitis

-

Otitis media

-

Alcoholism

-

CSF leak after head trauma

-

Functional or anatomic asplenia

-

Hypogammaglobulinemia

Pneumococcal meningitis

S pneumoniae, a gram-positive coccus, is the most common bacterial cause of meningitis. [2] In addition, it is the most common bacterial agent in meningitis associated with basilar skull fracture and CSF leak. It may be associated with other focal infections, such as pneumonia, sinusitis, or endocarditis (as, for example, in Austrian syndrome, which is the triad of pneumococcal meningitis, endocarditis, and pneumonia).

S pneumoniae is a common colonizer of the human nasopharynx; it is present in 5-10% of healthy adults and 20-40% of healthy children. It causes meningitis by escaping local host defenses and phagocytic mechanisms, either through choroid plexus seeding from bacteremia or through direct extension from sinusitis or otitis media.

Patients with the following conditions are at increased risk for S pneumoniae meningitis:

-

Hyposplenism

-

Hypogammaglobulinemia

-

Multiple myeloma

-

Glucocorticoid treatment

-

Defective complement (C1-C4)

-

Diabetes mellitus

-

Renal insufficiency

-

Alcoholism

-

Malnutrition

-

Chronic liver disease

Streptococcus agalactiae meningitis

Streptococcus agalactiae (group B streptococcus [GBS]) is a gram-positive coccus that inhabits the lower GI tract. It also colonizes the female genital tract at a rate of 5-40%, which explains why it is the most common agent of neonatal meningitis (associated with 70% of cases). Routine testing and treatment of pregnant females for GBS has led to a decrease in neonatal meningitis with this organism.

Predisposing risks in adults include the following:

-

Diabetes mellitus

-

Pregnancy

-

Alcoholism

-

Hepatic failure

-

Renal failure

-

Corticosteroid treatment

In 43% of adult cases, however, no underlying disease is present.

Meningococcal meningitis

N meningitidis is a gram-negative diplococcus that is carried in the nasopharynx of otherwise healthy individuals. It initiates invasion by penetrating the airway epithelial surface. The precise mechanism by which this occurs is unclear, but recent viral or mycoplasmal infection has been reported to disrupt the epithelial surface and facilitate invasion by meningococcus.

Most sporadic cases of meningococcal meningitis (95-97%) are caused by serogroups B, C, and Y, whereas the A and C strains are observed in epidemics (< 3% of cases). N meningitidis is one of the leading causes of bacterial meningitis in children and young adults, but the incidence has decreased with use of the conjugate meningococcal vaccine. [9]

Risk factors for meningococcal meningitis include the following:

-

Deficiencies in terminal complement components (eg, membrane attack complex, C5-C9), which increases attack rates but is associated with surprisingly lower mortality rates

-

Properdin defects that increase the risk of invasive disease

-

Antecedent viral infection, chronic medical illness, corticosteroid use, and active or passive smoking

-

Crowded living conditions, as is observed in college dormitories (college freshmen living in dormitories are at highest risk) and military facilities, which has been reported in clustering of cases

Listeria monocytogenes meningitis

Listeria monocytogenes is a small gram-positive bacillus that causes 3% of bacterial meningitis cases and is associated with one of the highest mortalities (20%). [7] The organism is widespread in nature and has been isolated in the stool of 5% of healthy adults. Most human cases appear to be food-borne.

L monocytogenes is a common food contaminant, with a recovery rate of up to 70% from raw meat, vegetables, and meats. Outbreaks have been associated with consumption of contaminated coleslaw, milk, cheese, and alfalfa tablets.

Groups at risk include the following:

-

Pregnant individuals

-

Infants and children

-

Elderly individuals (>60 years)

-

Patients with alcoholism

-

Adults who are immunosuppressed (eg, steroid users, transplant recipients, or persons with AIDS)

-

Individuals with chronic liver and renal disease

-

Individuals with diabetes

-

Persons with iron-overload conditions (eg, hemochromatosis or transfusion-induced iron overload)

Meningitis caused by gram-negative bacilli

Aerobic gram-negative bacilli include the following:

-

Escherichia coli

-

Klebsiella pneumoniae

-

Serratia marcescens

-

P aeruginosa

-

Salmonella species

Gram-negative bacilli can cause meningitis in certain groups of patients. E coli is a common agent of meningitis among neonates. Other predisposing risk factors for meningitis associated with gram-negative bacilli include the following:

-

Neurosurgical procedures or intracranial manipulation

-

Old age

-

Immunosuppression

-

High-grade gram-negative bacillary bacteremia

-

Disseminated strongyloidiasis

Disseminated strongyloidiasis has been reported as a classic cause of gram-negative bacillary bacteremia, as a result of the translocation of gut microflora with the Strongyloides stercoralis larvae during hyperinfection syndrome.

Staphylococcal meningitis

Staphylococci are gram-positive cocci that are part of the normal skin flora. Meningitis caused by staphylococci is associated with the following risk factors:

-

Neurosurgery

-

Head trauma

-

Presence of CSF shunts

-

Infective endocarditis and paraspinal infection

S epidermidis is the most common cause of meningitis in patients with CNS (ie, ventriculoperitoneal) shunts.

Aseptic meningitis

Aseptic meningitis is one of the most common infections of the meninges. Although viruses are the most common cause of aseptic meningitis, however, aseptic meningitis can also be caused by bacteria, fungi, and parasites. It is noteworthy that partially treated bacterial meningitis accounts for a large number of meningitis cases with a negative microbiologic workup.

In many cases, a cause of meningitis is not apparent after initial evaluation, and the disease therefore is classified as aseptic meningitis. These patients characteristically have an acute onset of meningeal symptoms, fever, and CSF pleocytosis that is usually prominently lymphocytic.

When the cause of aseptic meningitis is discovered, the disease can be reclassified according to its etiology. If appropriate diagnostic methods are performed, a specific viral etiology is identified in 55-70% of cases of aseptic meningitis. However, the condition also can be caused by bacterial, fungal, mycobacterial, and parasitic agents.

If, after an extensive workup, aseptic meningitis is found to have a viral etiology, it can be reclassified as a form of acute viral meningitis (eg, enteroviral meningitis or herpes simplex virus [HSV] meningitis).

Table 2. Infectious Agents Causing Aseptic Meningitis (Open Table in a new window)

Category |

Agent |

||

Bacteria |

Partially treated bacterial meningitis Listeria monocytogenes Brucella spp Rickettsia rickettsii Ehrlichia spp Mycoplasma pneumoniae Borrelia burgdorferi Treponema pallidum Leptospira spp Mycobacterium tuberculosis Nocardia spp |

||

Parasites |

Naegleria fowleri Acanthamoeba spp Balamuthia spp Angiostrongylus cantonensis Gnathostoma spinigerum Baylisascaris procyonis Strongyloides stercoralis Taenia solium (cysticercosis) Toxocara spp |

||

Fungi |

Cryptococcus neoformans Coccidioides immitis Blastomyces dermatitidis Histoplasma capsulatum Candida spp Aspergillus spp |

||

Viruses |

Enterovirus |

Poliovirus Echovirus Coxsackievirus A Coxsackievirus B Enterovirus 68-71 |

|

Herpesvirus (HSV) |

HSV-1 and HSV-2 Varicella-zoster virus Epstein-Barr virus Cytomegalovirus HHV-6 and HHV-7 |

||

Paramyxovirus |

Mumps virus Measles virus |

||

Togavirus |

Rubella virus |

||

Flavivirus |

West Nile virus Japanese encephalitis virus St Louis encephalitis virus |

||

Bunyavirus |

California encephalitis virus La Crosse encephalitis virus |

||

Alphavirus |

Eastern equine encephalitis virus Western equine encephalitis virus Venezuelan encephalitis virus |

||

Reovirus |

Colorado tick fever virus |

||

Arenavirus |

LCM virus |

||

Rhabdovirus |

Rabies virus |

||

Retrovirus |

HIV |

||

HHV = human herpesvirus; HSV = herpes simplex virus; LCM = lymphocytic choriomeningitis. |

|||

Enteroviruses account for of the majority of cases of aseptic meningitis in children. Enteroviruses belong to the family Picornaviridae and are further classified as follows:

-

Poliovirus (3 serotypes)

-

Coxsackievirus A (23 serotypes)

-

Coxsackievirus B (6 serotypes)

-

Echovirus (31 serotypes)

-

Newly recognized enterovirus serotypes 68-71

Enteroviruses are usually spread by fecal-oral or respiratory routes. Infection occurs during summer and fall in temperate climates and year-round in tropical regions.

The nonpolio enteroviruses (NPEVs) account for approximately 90% of cases of viral meningitis in which a specific pathogen can be identified.

Echovirus 30 was reported as the cause of an epidemic in Japan in 1991. It was also reported as the cause of 20% of cases of aseptic meningitis reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in 1991.

The Herpesviridae family consists of large, DNA-containing enveloped viruses. Eight members are known to cause human infections, and all have been implicated in meningitis syndromes, with the exception of HHV-8 or Kaposi sarcoma–associated virus.

HSV accounts for 0.5% to 3% of cases of aseptic meningitis; it most commonly is associated with primary genital infection and is less likely during recurrences. HSV-1 is a cause of encephalitis, whereas HSV-2 more commonly causes meningitis. Although Mollaret syndrome (a recurrent, but benign, aseptic meningitis syndrome) is more frequently associated with HSV-2, HSV-1 also has been implicated as a cause.

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV, or HHV-4) and cytomegalovirus (CMV, or HHV-5) infection may manifest as meningitis in patients with the mononucleosis syndrome. Varicella-zoster virus (VZV, or HHV-3) and CMV cause meningitis in immunocompromised hosts, especially patients with AIDS and transplant recipients. HHV-6 and HHV-7 have been reported to cause meningitis in transplant recipients.

The most common arthropod-borne viruses are West Nile virus, St Louis encephalitis virus (a flavivirus), Colorado tick fever virus, and California encephalitis virus (bunyavirus group, including La Crosse encephalitis virus). St Louis encephalitis virus is a mosquito-borne flavivirus that may cause a febrile syndrome, aseptic meningitis syndrome, and encephalitis. Other members of the flavivirus group that may cause aseptic meningitis include tick-borne encephalitis virus, Powassan encephalitis, and Japanese encephalitis virus. [10]

California encephalitis is a common childhood disease of the CNS that is caused by a virus in the genus Bunyavirus. Most of the cases of California encephalitis probably are caused by mosquito-borne La Crosse encephalitis virus.

LCM virus is a member of the arenaviruses, a family of single-stranded, RNA-containing viruses in which rodents are the animal reservoir. The modes of transmission include aerosols and direct contact with rodents. Outbreaks also have been traced to infected laboratory mice and hamsters.

The mumps virus is the most common cause of aseptic meningitis in unimmunized populations, occurring in 30% of all patients with mumps. Upon exposure, an incubation period of approximately 5 to 10 days ensues, followed by a nonspecific febrile illness and an acute onset of aseptic meningitis. This may be associated with orchitis, arthritis, myocarditis, and alopecia.

Patients with acute HIV infection may present with aseptic meningitis syndrome, usually as part of the mononucleosis-like acute seroconversion phenomenon. HIV always should be suspected as a cause of aseptic meningitis in a patient with risk factors such as IV drug use or high-risk sexual behaviors. These patients will have negative results on HIV serologic tests (eg, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay [ELISA] and Western blot); the diagnosis is made by the detection of serum HIV RNA on polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing or of HIV p24 antigen.

Adenovirus (serotypes 1, 6, 7, and 12) has been associated with cases of meningoencephalitis. Chronic meningoencephalitis has been reported with serotypes 7, 12, and 32. The infection usually acquired through a respiratory route.

Toscana virus meningitis or encephalitis should be considered in travelers returning from a Mediterranean country (eg, Italy, Spain, or Greece) during the summer. Toscana viruses are transmitted by the bite of a sandfly. Toscana virus infection can be diagnosed by performing paired serologies and CSF PCR, which in the United States is available only through the CDC. [10]

Astrovirus MLB2, usually a gastrointestinal virus, and Cache Valley virus in an immunosuppressed individual are newly identified as causes of meningitis. [11, 12]

Chronic meningitis

Chronic meningitis is a constellation of signs and symptoms of meningeal irritation associated with CSF pleocytosis that persists for longer than 4 weeks.

Chronic meningitis can be caused by a wide range of infectious and noninfectious etiologies (see Table 3 below).

Table 3. Causes of Chronic Meningitis (Open Table in a new window)

Category |

Agent |

Bacteria |

Mycobacterium tuberculosis Borrelia burgdorferi Treponema pallidum Brucella spp Francisella tularensis Nocardia spp Actinomyces spp |

Fungi |

Cryptococcus neoformans Coccidioides immitis Blastomyces dermatitidis Histoplasma capsulatum Candida albicans Aspergillus spp Sporothrix schenckii |

Parasites |

Acanthamoeba spp Naegleria fowleri Angiostrongylus cantonensis Gnathostoma spinigerum Baylisascarisprocyonis Schistosoma spp Strongyloides stercoralis Echinococcus granulosus |

Brucellae are small gram-negative coccobacilli that cause zoonoses as a result of infection with Brucella abortus, Brucella melitensis, Brucella suis, or Brucella canis. Transmission to humans occurs after direct or indirect exposure to infected animals (eg, sheep, goats, or cattle). Direct infection of the CNS occurs in fewer than 5% of cases, with most patients presenting with acute or chronic meningitis.

Persons at risk for brucellosis include individuals who had contact with infected animals or their products (eg, through intake of unpasteurized milk products). Veterinarians, abattoir workers, and laboratory workers dealing with these animals also are at risk.

M tuberculosis is an acid-fast bacillus that causes a broad range of clinical illnesses that can affect virtually any organ of the body. It is spread through airborne droplet nuclei, and it infects one third of the world’s population. Involvement of the CNS with tuberculous meningitis usually is caused by rupture of a tubercle into the subarachnoid space

Tuberculous meningitis should always be considered in the differential diagnosis of patients with aseptic meningitis or chronic meningitis syndromes, especially those with basilar meningitis, symptoms of more than 5 days’ duration, or cranial nerve palsies. If tuberculous meningitis is suspected, antituberculosis therapy, with or without steroids, should be empirically started.

Treponema pallidum is a slender, tightly coiled spirochete that is usually acquired by sexual contact. Other modes of transmission include direct contact with an active lesion, passage through the placenta, and blood transfusion (rare).

Borrelia burgdorferi, a tick-borne spirochete, is the agent of Lyme disease, the most common vector-borne disease in the United States. Meningitis may be part of a triad of neurologic manifestations of Lyme disease that also includes cranial neuritis and radiculoneuritis. Lyme disease meningitis typically is associated with a facial palsy that can be bilateral.

Cryptococcus neoformans is an encapsulated, yeastlike fungus that is ubiquitous. It has been found in high concentrations in aged pigeon droppings and pigeon nesting places. The 4 serotypes are designated A through D, with the A serotype causing most human infections. Onset of cryptococcal meningitis may be acute, especially among patients with AIDS.

Numerous cases occur in healthy hosts (eg, persons with no known T-cell defect); however, approximately 50-80% of cases occur in immunocompromised hosts. At particular risk are individuals with defects of T-cell–mediated immunity, such as persons with AIDS, organ transplant recipients, and other patients who use steroids, cyclosporine, and other immunosuppressants. Cryptococcal meningitis also has been reported in patients with idiopathic CD-4 lymphopenia, Hodgkin disease, sarcoidosis, and cirrhosis.

Coccidioides immitis is a soil-based, dimorphic fungus that exists in mycelial and yeast (spherule) forms. Persons at risk for coccidioidal meningitis include individuals exposed to the endemic regions (eg, tourists and local populations) and those with immune deficiency (eg, persons with AIDS and organ transplant recipients).

Blastomyces dermatitidis is a dimorphic fungus that has been reported to be endemic in North America (eg, in the Mississippi and Ohio River basins). It also has been isolated from parts of Central America, South America, the Middle East, and India. Its natural habitat is not well defined. Soil that is rich in decaying matter and environments around riverbanks and waterways have been demonstrated to harbor B dermatitidis during outbreaks and are thought to be risk factors for acquiring the infection.

Inhalation of the conidia establishes a pulmonary infection. Dissemination may occur in certain individuals, including those with underlying immune deficiency (eg, from HIV or pharmaceutical agents) and extremes of age, and may involve the skin, bones and joints, genitourinary tract, and CNS. Involvement of the CNS occurs in fewer than 5% of cases.

Histoplasma capsulatum is one of the dimorphic fungi that exist in mycelial and yeast forms. It usually is found in soil and occasionally can cause a chronic meningitis. The preferred means of making the diagnosis is CSF histoplasma antigen detection.

Candida species are ubiquitous in nature. They are normal commensals in humans and are found in the skin, the GI tract, and the female genital tract. The most common species is Candida albicans, but the incidence of non-albicans candidal infections (eg, Candida tropicalis) is increasing, including species with antifungal resistance (eg, Candida krusei and Candida glabrata).

Involvement of the CNS usually follows hematogenous dissemination. The most important predisposing risks for acquiring disseminated candidal infection appear to be iatrogenic (eg, the administration of broad-spectrum antibiotics and the use of indwelling devices such as urinary and vascular catheters). Prematurity in neonates is considered a predisposing risk factor as well. Infection also may follow neurosurgical procedures, such as placement of ventricular shunts.

Sporothrix schenckii is an endemic dimorphic fungus that often is isolated from soil, plants, and plant products. Human infections are characteristically lymphocutaneous. Extracutaneous manifestations of sporotrichosis may occur, though meningeal sporotrichosis, which is the most severe form, is a rare complication. AIDS is a reported underlying risk factor in many described cases and is associated with a poor outcome.

Infection with free-living amoebas is an infrequent but often life-threatening human illness, even in immunocompetent individuals. N fowleri is the only species of Naegleria recognized to be pathogenic in humans, and it is the agent of primary amebic meningoencephalitis (PAM). The parasite has been isolated in lakes, pools, ponds, rivers, tap water, and soil.

Infection occurs when a person is swimming or playing in contaminated water sources (eg, inadequately chlorinated water and sources associated with poor decontamination techniques). The N fowleri amebas invade the CNS through the nasal mucosa and cribriform plate.

PAM occurs in 2 forms. The first is characterized by an acute onset of high fever, photophobia, headache, and altered mental status, similar to bacterial meningitis, occurring within 1 week after exposure. Because it is acquired via the nasal area, olfactory nerve involvement may manifest as abnormal smell sensation. Death occurs in 3 days in patients who are not treated. The second form, the subacute or chronic form, consists of an insidious onset of low-grade fever, headache, and focal neurologic signs. Duration of illness is weeks to a few months.

Acanthamoeba and Balamuthia cause granulomatous amebic encephalitis, which is a subacute opportunistic infection that spreads hematogenously from the primary site of infection (skin or lungs) to the CNS and causes an encephalitis syndrome. These cases can be difficult to distinguish from culture-negative meningitis.

Angiostrongylus cantonensis, the rat lungworm, can cause eosinophilic meningitis (pleocytosis with more than 10% eosinophils) in humans. The adult parasite resides in the lungs of rats. Its eggs hatch, and the larval stages are expelled in the feces. The larvae develop in the intermediate host, usually land snails, freshwater prawns, and crabs. Humans acquire the infection by ingesting raw mollusks.

Gnathostoma spinigerum, a GI parasite of wild and domestic dogs and cats, may cause eosinophilic meningoencephalitis. Humans acquire the infection after ingesting undercooked infected fish and poultry.

Baylisascaris procyonis is an ascarid parasite that is prevalent in the raccoon populations in the United States and rarely causes human eosinophilic meningoencephalitis. Human infections occur after accidental ingestion of food products contaminated with raccoon feces.

Additional causes of meningitis

Congenital malformation of the stapedial footplate has been implicated in the development of meningitis. Head and neck surgery, penetrating head injury, comminuted skull fracture, and osteomyelitic erosion infrequently may result in direct implantation of bacteria into the meninges. Skull fractures can tear the dura and cause a CSF fistula, especially in the region of the frontal ethmoid sinuses. Patients with any of these conditions are at risk for bacterial meningitis.

Epidemiology

Epidemiology of bacterial meningitis

The incidence of meningitis varies according to the specific etiologic agent, as well as in conjunction with a nation’s medical resources. The incidence is presumed to be higher in developing countries because of less access to preventive services, such as vaccination. In these countries, the incidence has been reported to be 10 times higher than that in developed countries. Meningitis affects people of all races. In the United States, Black people have a higher reported rate of meningitis than White people and Hispanic people

With almost 4100 cases and 500 deaths occurring annually in the United States, bacterial meningitis continues to be a significant source of morbidity and mortality. The annual incidence in the United States is 1.33 cases per 100,000 population

During a 1998-2007 survey, the incidence of meningitis fell by 31%, a decrease that can be credited to vaccination programs. The rate of bacterial meningitis declined by 55% in the early 1990s when Hib conjugate vaccine for infants was introduced. The number of cases of invasive H influenzae disease among children younger than 5 years that were reported to the CDC declined from 20,000 in 1987 to 255 in 1998. This shift has reportedly been less dramatic in developing countries, where the use of Hib vaccine is not as widespread. [7]

Pneumococcal vaccine and universal screening of pregnant women for group B streptococcus have further decreased the incidence of meningitis among young children but the burden of bacterial meningitis is now borne by older adults.

Table 4. Changing Epidemiology of Acute Bacterial Meningitis in United States* (Open Table in a new window)

Bacteria |

1978-1981 |

1986 |

1995 |

1998-2007 |

|

Haemophilus influenzae |

48% |

45% |

7% |

6.7% |

|

Listeria monocytogenes |

2% |

3% |

8% |

3.4% |

|

Neisseria meningitidis |

20% |

14% |

25% |

13.9% |

|

Streptococcus agalactiae (group B streptococcus) |

3% |

6% |

12% |

18.1% |

|

Streptococcus pneumoniae |

13% |

18% |

47% |

58% |

|

*Nosocomial meningitis is not included; these data include only the 5 major meningeal pathogens. |

|||||

In England and Wales the annual incidence of pneumococcal meningitis remained unchanged after PCV7 introduction but dropped by 48% after PCV13 replaced PCV7. The greatest decline in pneumococcal meningitis incidence (70%) was observed among children < 5 years of age. By 2015–16, PCV13-serotype meningitis was rare, and nearly all cases were caused by non-PCV13 serotypes. PCV has reduced pneumococcal infections caused by vaccine strains, most of which were resistant, by more than 90% in children. Since PCV introduction among US children in 2000, the rates of antibiotic-resistant invasive pneumococcal infections caused by vaccine strains decreased by 97% among children younger than 5 years and by more than 60% among adults. [8]

Meningococcal disease occurs worldwide, with the highest incidence of disease found in the meningitis belt of sub-Saharan Africa. Following a mass vaccination campaign with a monovalent serogroup A meningococcal conjugate vaccine, epidemic due to serogroup A was eliminated but now more epidemics are primarily due to serogroup C and W. In the United States, meningococcal disease incidence has steadily declined since 1995 (1.20 cases/100,000 persons) to a historic low of 0.11 cases/100,000 persons in 2017. [13] The rates of disease are highest in children younger than 1 year, with a second peak in adolescence. N meningitidis causes approximately 4 cases per 100,000 children aged 1 to 23 months. Among adolescents and young adults, those aged 16 through 23 years have the highest rates of meningococcal disease. Historically, most meningococcal disease outbreaks on university campuses in the United States were caused by serogroup C. However, serogroup B has caused all known US university-based outbreaks since 2011, likely in part because of high Men ACWY coverage in adolescents. [14, 15] The risk for secondary meningitis is 1% for family contacts and 0.1% for daycare contacts. The rate of meningitis caused by S pneumoniae is 6.5 cases per 100,000 children aged 1 to 23 months.

Epidemiology of Aseptic and Viral meningitis

Viruses are the major cause of aseptic meningitis.

Aseptic meningitis has a reported incidence of 10.9 cases per 100,000 person-years. It occurs in individuals of all ages but is more common in children, especially during summer. No racial differences are reported.

The incidence of viral meningitis has been estimated to range from 0.26 to 17 cases per 100,000 people. During 1988-1999, viral meningitis accounted for 50.2% of all meningitis-associated hospitalization in the United States. In 2006, more than half (54.6 percent) of all meningitis-related hospitalizations were attributed to a virus, whereas bacterial meningitis accounted for 21.8 percent of all meningitis-related hospital stays. Most (71%) of viral meningitis hospitalizations occurred from May to October. In a study from the United Kingdom, the incidence of viral meningitis from September 2011 to 2014 was 2.73 per 100,000 and that of bacterial meningitis was 1.24 per 100,000.

In a study from Denmark, the incidence of viral meningitis hospitalization was highest after birth, with a secondary peak at age 5 years. Khetsuriani et al reported average US annual hospitalization rates of 213 per 100,000 infants, 14 per 100,000 children aged 1 to 4 years, and 14 per 100,000 youth aged 5 to 19 years. [16, 17, 18, 19, 20]

Nonpolio Enteroviruses (NPEVs) include the coxsackieviruses, echoviruses, and newer numbered EVs (a total of 67 distinct serotypes). In the United States alone, the NPEVs cause an estimated 10 to 15 million symptomatic infections annually.

Prognosis

Patients with bacterial meningitis who present with an impaired level of consciousness, hypotension, or seizures are at increased risk for neurologic sequelae or death. [11]

In bacterial meningitis, several risk factors are associated with death and with neurologic disability. A risk score has been derived and validated in adults with bacterial meningitis. This score includes the following variables, which are associated with an adverse clinical outcome:

-

Older age

-

Increased heart rate

-

Lower Glasgow Coma Scale score

-

Cranial nerve palsies

-

CSF leukocyte count lower than 1000/μL

-

Gram-positive cocci on CSF Gram stain

Even with effective antimicrobial therapy, significant neurologic complications occur in as many as 30% of survivors of bacterial meningitis. Close monitoring for the development of these complications is essential.

Mortality for bacterial meningitis is highest in the first year of life, decreases in midlife, and increases again in old age. Bacterial meningitis is fatal in 1 in 10 cases, and 1 of every 7 survivors is left with a severe handicap, such as deafness or brain injury.

Among bacterial pathogens, S pneumoniae causes the highest mortality (20-30% in adults, 10% in children) and morbidity (15%) in meningitis. If severe neurologic impairment is evident at the time of presentation (or if the onset of illness is extremely rapid), mortality is 50-90% and morbidity is even higher, even with immediate medical treatment. Meningitis caused by L monocytogenes or gram-negative bacilli also has a higher case-fatality rate than meningitis caused by other bacterial agents.

Reported overall mortality for meningitis from specific bacterial organisms is as follows:

-

S pneumoniae - 19-26%

-

H influenzae - 3-6%

-

N meningitidis - 3-13%

-

L monocytogenes - 15-29%

Patients with meningococcal meningitis have a better prognosis than do those with pneumococcal meningitis, with a mortality of 4-5%; however, patients with meningococcemia have a poor prognosis, with a mortality of 20-30%.

Advanced bacterial meningitis can lead to brain damage, coma, and death. In 50% of patients, several complications may develop in the days to weeks after infection. Long-term sequelae are seen in as many as 30% of survivors and vary with etiologic agent, patient age, presenting features, and hospital course. Patients usually have subtle CNS changes.

Serious complications include the following:

-

Hearing loss

-

Cortical blindness

-

Other cranial nerve dysfunction

-

Paralysis

-

Muscular hypertonia

-

Ataxia

-

Multiple seizures

-

Mental motor impairment

-

Focal paralysis

-

Ataxia

-

Subdural effusions

-

Hydrocephalus

-

Cerebral atrophy

Risk factors for hearing loss after pneumococcal meningitis are female sex, older age, severe meningitis, and infection with certain pneumococcal serotypes (eg, 12F). [21] Delayed complications include the following:

-

Decreased hearing or deafness

-

Delayed cerebral thrombosis [22]

-

Other cranial nerve dysfunctions

-

Multiple seizures

-

Focal paralysis

-

Subdural effusions

-

Hydrocephalus

-

Intellectual deficits

-

Ataxia

-

Blindness

-

Waterhouse-Friderichsen syndrome

-

Peripheral gangrene

Seizures are a common and important complication, occurring in approximately one fifth of patients. The incidence is higher in patients younger than 1 year, reaching 40%. Approximately one half of patients with this complication have repeated seizures. Patients may die as a result of diffuse CNS ischemic injury or systemic complications.

The prognosis in patients with meningitis caused by opportunistic pathogens depends on the underlying immune function of the host. Many patients who survive the disease require lifelong suppressive therapy (eg, long-term fluconazole for suppression in patients with HIV-associated cryptococcal meningitis).

The mortality for viral meningitis without encephalitis is less than 1%. In patients with deficient humoral immunity (eg, agammaglobulinemia), enteroviral meningitis may have a fatal outcome. Patients with viral meningitis usually have a good prognosis for recovery. The prognosis is worse for patients at the extremes of age (ie, < 2 or >60 years) and those with significant comorbidities and underlying immunodeficiency.

Patient Education

Patients and parents of young children should be educated about the benefits of vaccination in preventing meningitis. Vaccination against N meningitidis is recommended for all US college students.

Close contacts of patients with known or suspected N meningitidis or Hib meningitis may require education regarding the need for prophylaxis. All contacts should be instructed to come to the emergency department immediately at the first sign of fever, sore throat, rash, or symptoms of meningitis. Rifampin prophylaxis only eradicates the organism from the nasopharynx; it is ineffective against invasive disease.

For patient education information, see the Brain and Nervous System Center and the Children’s Health Center, as well as Meningitis in Adults, Meningitis in Children, Brain Infection, and Spinal Tap.

-

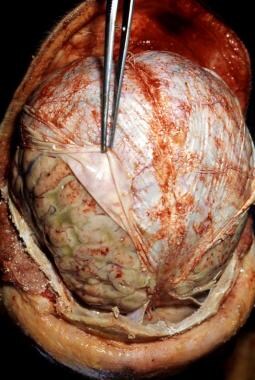

Pneumococcal meningitis in a patient with alcoholism. Courtesy of the CDC/Dr. Edwin P. Ewing, Jr.

-

Acute bacterial meningitis. This axial nonenhanced computed tomography scan shows mild ventriculomegaly and sulcal effacement.

-

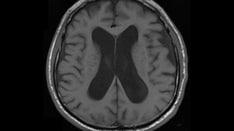

Acute bacterial meningitis. This axial T2-weighted magnetic resonance image shows only mild ventriculomegaly.

-

Acute bacterial meningitis. This contrast-enhanced, axial T1-weighted magnetic resonance image shows leptomeningeal enhancement (arrows).

-

Chronic mastoiditis and epidural empyema in a patient with bacterial meningitis. This axial computed tomography scan shows sclerosis of the temporal bone (chronic mastoiditis), an adjacent epidural empyema with marked dural enhancement (arrow), and the absence of left mastoid air.

-

Subdural empyema and arterial infarct in a patient with bacterial meningitis. This contrast-enhanced axial computed tomography scan shows left-sided parenchymal hypoattenuation in the middle cerebral artery territory, with marked herniation and a prominent subdural empyema.

Tables

What would you like to print?

- Overview

- Presentation

- DDx

- Workup

- Treatment

- Approach Considerations

- Treatment of Subacute Meningitis

- Treatment of Bacterial Meningitis

- Treatment of Viral Meningitis

- Treatment of Fungal Meningitis

- Treatment of Tuberculous Meningitis

- Treatment of Syphilitic Meningitis

- Treatment of Parasitic Meningitis

- Treatment of Lyme Meningitis

- Prevention

- Consultations

- Long-Term Monitoring

- Show All

- Guidelines

- Medication

- Medication Summary

- Sulfonamides

- Tetracyclines

- Carbapenems

- Fluoroquinolones

- Antibiotics, Miscellaneous

- Glycopeptides

- Aminoglycosides

- Penicillins, Amino

- Penicillins, Natural

- Cephalosporins, 3rd Generation

- Antivirals, CMV

- Antivirals, Other

- Antifungals, Systemic

- Antituberculous Agents

- Vaccines, Inactivated, Bacterial

- Corticosteroids

- Diuretics, Osmotic Agents

- Diuretics, Loop

- Anticonvulsants, Hydantoins

- Anticonvulsants, Barbiturates

- Anticonvulsants, Other

- Show All

- Questions & Answers

- Media Gallery

- Tables

- References