Practice Essentials

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is one of the two major types of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), along with Crohn disease (CD). Unlike Crohn disease, which can affect any part of the gastrointestinal tract, ulcerative colitis characteristically involves the large bowel (see the image below). Ulcerative colitis is a lifelong illness that has a profound emotional and social impact on the affected patients.

Signs and symptoms

Patients with UC predominantly complain of the following:

-

Rectal bleeding

-

Frequent stools

-

Mucous discharge from the rectum

-

Tenesmus (occasionally)

-

Lower abdominal pain and severe dehydration from purulent rectal discharge (in severe cases, especially in the elderly)

In some cases, UC has a fulminant course marked by the following:

-

Severe diarrhea and cramps

-

Fever

-

Leukocytosis

-

Abdominal distention

UC is associated with various extracolonic manifestations, as follows:

-

Uveitis

-

Pyoderma gangrenosum

-

Pleuritis

-

Erythema nodosum

-

Ankylosing spondylitis

-

Spondyloarthropathies

Other conditions associated with UC include the following:

-

Recurrent subcutaneous abscesses unrelated to pyoderma gangrenosum [1]

-

Multiple sclerosis [2]

-

Immunobullous disease of the skin [3]

Physical findings are typically normal in mild disease, except for mild tenderness in the lower left abdominal quadrant (tenderness or cramps are generally present in moderate to severe disease [4] ). In severe disease, the following may be observed:

-

Fever

-

Tachycardia

-

Significant abdominal tenderness

-

Weight loss

The severity of UC can be graded as follows:

-

Mild: Bleeding per rectum, fewer than four bowel motions per day

-

Moderate: Bleeding per rectum, more than four bowel motions per day

-

Severe: Bleeding per rectum, more than four bowel motions per day, and a systemic illness with hypoalbuminemia (< 30 g/L)

See Presentation for more detail.

Diagnosis

Laboratory studies are useful principally in determining the extent of the disease, excluding other diagnoses, and in assessing the patient’s nutritional status. They may include the following:

-

Serologic markers (eg, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies [ANCA], anti– Saccharomyces cerevisiae antibodies [ASCA])

-

Complete blood cell (CBC) count

-

Comprehensive metabolic panel

-

Inflammation markers (eg, erythrocyte sedimentation rate [ESR], C-reactive protein [CRP])

-

Stool assays

Diagnosis is best made with endoscopy and biopsy, on which the following are characteristic findings:

-

Abnormal erythematous mucosa, with or without ulceration, extending from the rectum to a part or all of the colon

-

Uniform inflammation, without intervening areas of normal mucosa (skip lesions tend to characterize Crohn disease)

-

Contact bleeding may also be observed, with mucus identified in the lumen of the bowel

The extent of disease is defined by the following findings on endoscopy:

-

Extensive disease: Evidence of UC proximal to the splenic flexure

-

Left-side disease: UC present in the descending colon up to, but not proximal to, the splenic flexure

-

Proctosigmoiditis: Disease limited to the rectum with or without sigmoid involvement

Imaging modalities that may be considered include the following:

-

Plain abdominal radiography

-

Double-contrast barium enema examination

-

Cross-sectional imaging studies (eg, ultrasonography, magnetic resonance imaging, computed tomography scanning)

-

Radionuclide studies

-

Angiography

See Workup for more detail.

Management

Medical treatment of mild UC includes the following:

-

Mild disease confined to the rectum: Topical mesalazine via suppository (preferred) or budesonide rectal foam

-

Left-side colonic disease: Mesalazine suppository and oral aminosalicylate (oral mesalazine is preferred to oral sulfasalazine)

-

Systemic steroids, when disease does not quickly respond to aminosalicylates

-

Oral budesonide

-

After remission, long-term maintenance therapy (eg, once-daily mesalazine)

Medical treatment of acute, severe UC may include the following:

-

Hospitalization

-

Intravenous high-dose corticosteroids

-

Alternative induction medications: Cyclosporine, tacrolimus, infliximab, adalimumab, golimumab

Indications for urgent surgery include the following:

-

Toxic megacolon refractory to medical management

-

Fulminant attack refractory to medical management

-

Uncontrolled colonic bleeding

Indications for elective surgery include the following:

-

Long-term steroid dependence

-

Dysplasia or adenocarcinoma found on screening biopsy

-

Disease being present for 7-10 years

Surgical options include the following [5, 6, 7] :

-

Total colectomy (panproctocolectomy) and ileostomy

-

Total colectomy

-

Ileoanal pouch reconstruction or ileorectal anastomosis

-

In an emergency, subtotal colectomy with end-ileostomy

See Treatment and Medication for more detail.

Background

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is one of the two major types of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), along with Crohn disease (CD). Unlike Crohn disease, which can affect any part of the gastrointestinal tract, ulcerative colitis characteristically involves the large bowel (see the images below). Ulcerative colitis is a lifelong illness that has a profound emotional and social impact on the affected patients.

Ulcerative Colitis. Single-contrast enema study in a patient with total colitis shows mucosal ulcers with a variety of shapes, including collar-button ulcers (yellow arrow), in which undermining of the ulcers occurs, and double-tracking ulcers (red arrow), in which the ulcers are longitudinally orientated.

Ulcerative Colitis. Single-contrast enema study in a patient with total colitis shows mucosal ulcers with a variety of shapes, including collar-button ulcers (yellow arrow), in which undermining of the ulcers occurs, and double-tracking ulcers (red arrow), in which the ulcers are longitudinally orientated.

The exact etiology of ulcerative colitis is unknown, but the disease appears to be multifactorial and polygenic. The proposed causes include environmental factors, immune dysfunction, and a likely genetic predisposition. Some have suggested that children of below-average birth weight who are born to mothers with ulcerative colitis have a greater risk of developing the disease. (See Etiology.)

Histocompatibility human leukocyte antigen (HLA)–B27 is identified in most patients with ulcerative colitis, although this finding is not causally associated with the condition and the finding of HLA-B27 does not imply a substantially increased risk for ulcerative colitis. Ulcerative colitis may also be influenced by diet, although diet is thought to play a secondary role. Food or bacterial antigens might exert an effect on the already damaged mucosal lining, which has increased permeability.

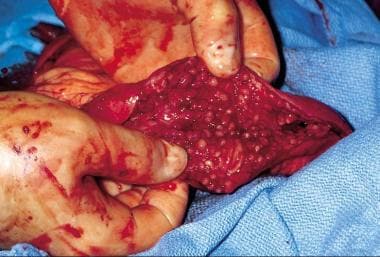

Grossly, the colonic mucosa appears hyperemic, with loss of the normal vascular pattern. The mucosa is granular and friable. Frequently, broad-based ulcerations cause islands of normal mucosa to appear polypoid, leading to the term pseudopolyp (see the image below).

The bowel wall is thin or of normal thickness, but edema, the accumulation of fat, and hypertrophy of the muscle layer may give the impression of a thickened bowel wall. The disease is largely confined to the mucosa and, to a lesser extent, the submucosa. Muscle-layer and serosal involvement is very rare; such involvement is seen in patients with severe disease, particularly toxic dilatation, and reflects a secondary effect of the severe disease rather than primary ulcerative colitis pathogenesis. Early disease manifests as hemorrhagic inflammation with loss of the normal vascular pattern, petechial hemorrhages, and bleeding. Edema is present, and large areas become denuded of mucosa. Undermining of the mucosa leads to the formation of crypt abscesses, which are the hallmark of the disease. (See Presentation.)

The diagnosis of ulcerative colitis is best made with endoscopy and mucosal biopsy for histopathology. Laboratory studies are helpful to exclude other diagnoses and assess the patient's nutritional status, but serologic markers can assist in the diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease. Radiographic imaging has an important role in the workup of patients with suspected inflammatory bowel disease and in the differentiation of ulcerative colitis from Crohn disease by demonstrating fistulae or the presence of small bowel disease seen only in Crohn disease. (See Workup.)

The initial treatment for ulcerative colitis includes mesalamine, corticosteroids, anti-inflammatory agents, antidiarrheal agents, and rehydration (see Medication). Surgery is considered if medical treatment fails or if a surgical emergency develops. (See Treatment.)

For more information, go to Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Crohn Disease.

For more Clinical Practice Guidelines, go to Guidelines.

Additional information can be found at Colitis Foundation of America (CCFA).

Anatomy

Ulcerative colitis (UC) extends proximally from the anal verge in an uninterrupted pattern to involve part or the entire colon. The rectum is involved in more than 95% of cases; some authorities believe that the rectum is always involved in untreated patients. Rectal involvement occurs even when the rest of the colon is spared.

Ulcerative colitis occasionally involves the terminal ileum, as a result of an incompetent ileocecal valve. In these cases, which may constitute as many as 10% of patients, the reflux of noxious inflammatory mediators from the colon results in superficial mucosal inflammation of the terminal ileum, called backwash ileitis. [8, 9] Up to about 30 cm of the terminal ileum may be affected.

Pathophysiology

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a diffuse, nonspecific inflammatory disease whose etiology is unknown. [10] The colonic mucosa proximal from the rectum is persistently affected, frequently involving erosions and/or ulcers, as well as involving repeated cycles of relapse and remission and potential extraintestinal manifestations. [10]

A variety of immunologic changes have been documented in ulcerative colitis. Subsets of T cells accumulate in the lamina propria of the diseased colonic segment. In patients with ulcerative colitis, these T cells are cytotoxic to the colonic epithelium. This change is accompanied by an increase in the population of B cells and plasma cells, with increased production of immunoglobulin G (IgG) and immunoglobulin E (IgE). [11]

Anticolonic antibodies have been detected in patients with ulcerative colitis. A small proportion of patients with ulcerative colitis have antismooth muscle and anticytoskeletal antibodies.

Microscopically, acute and chronic inflammatory infiltrate of the lamina propria, crypt branching, and villous atrophy are present in ulcerative colitis. Microscopic changes also include inflammation of the crypts of Lieberkühn and abscesses. These findings are accompanied by a discharge of mucus from the goblet cells, the number of which is reduced as the disease progresses. The ulcerated areas are soon covered by granulation tissue. Excessive fibrosis is not a feature of the disease. The undermining of the mucosa and an excess of granulation tissue lead to the formation of polypoidal mucosal excrescences, which are known as inflammatory polyps or pseudopolyps.

Etiology

The exact etiology of ulcerative colitis (UC) is unknown, but certain factors have been found to be associated with the disease, and some hypotheses have been presented. Etiologic factors potentially contributing to ulcerative colitis include genetic factors, immune system reactions, environmental factors, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) use, low levels of antioxidants, psychological stress factors, a smoking history, and consumption of milk products. Certain types of food composition and the use of oral contraceptives may be associated with this condition. [10]

Some evidence exists to indicate smoking may be protective of ulcerative colitis, but a causal association remains unclear. [10] A systematic review and meta-analysis that evaluated the association between smoking and need for surgery in patients with inflammatory bowel disease found that current smokers with Crohn disease had an increased risk of intestinal resection surgery compared to their never-smoking counterparts, whereas in patients with ulcerative colitis, current and never smokers had similar rates of colectomy. [12] However, there was an increased risk for colectomy in former smokers with ulcerative colitis.

Genetics

The current hypothesis is that genetically susceptible individuals have abnormalities of the humoral and cell-mediated immunity and/or generalized enhanced reactivity against commensal intestinal bacteria, and that this dysregulated mucosal immune response predisposes to colonic inflammation. [13]

A family history of ulcerative colitis (observed in 1 in 6 relatives) is associated with a higher risk for developing the disease. Disease concordance has been documented in monozygotic twins. [14] Genetic association studies have identified multiple loci, [10] including some that are associated with both ulcerative colitis and Crohn disease; one relatively recently identified locus is also associated with the susceptibility to colorectal cancer (CDH1). [15]

Chromosomes are thought to be less stable in patients with ulcerative colitis, as measured with telomeric associations in peripheral leukocytes. [16] This phenomenon may also contribute to the increased cancer risk. Whether these abnormalities are the cause or the result of the intense systemic inflammatory response in ulcerative colitis is unresolved.

Immune reactions

Immune reactions that compromise the integrity of the intestinal epithelial barrier may contribute to ulcerative colitis. Serum and mucosal autoantibodies against intestinal epithelial cells may be involved. The presence of antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA) and anti– Saccharomyces cerevisiae antibodies (ASCA) is a well-known feature of inflammatory bowel disease. [17, 18, 19, 20, 21]

In addition, an immune modulatory abnormality has been assumed to be responsible for the lower incidence of ulcerative colitis in patients who have undergone previous appendectomy. The incidence of previous appendectomy is lower in patients with ulcerative colitis (4.5%) than in control subjects (19%), and a further protective effect is observed if the appendectomy was performed before the patient was age 20 years. [22] Also, patients in whom appendectomy was performed for inflammatory disorders (eg, appendicitis or mesenteric adenitis) seem to have a lower incidence of ulcerative colitis than patients who undergo appendectomy for other disorders such as nonspecific abdominal pain. [23]

Environmental factors

Environmental factors also play a role. For example, sulfate-reducing bacteria, which produce sulfides, are found in large numbers in patients with ulcerative colitis, and sulfide production is higher in patients with ulcerative colitis than in other people. Sulfide production is even higher in patients with active ulcerative colitis than in patients in remission. The bacterial microflora is altered in patients with active disease. [24] A decrease in Klebsiella species is seen in the ileum of patients relative to control subjects. This difference disappears after proctocolectomy.

NSAID use

NSAID use is higher in patients with ulcerative colitis than in control subjects, and one third of patients with an exacerbation of ulcerative colitis report recent NSAID use. This finding leads some clinicians to recommend avoidance of NSAID use in patients with ulcerative colitis. [25]

Other etiologic factors

Other factors that may be associated with ulcerative colitis include the following:

-

Vitamins A and E, both considered antioxidants, are found in low levels in as many as 16% of children with ulcerative colitis exacerbation. [26]

-

Psychological and psychosocial stress factors can play a role in the presentation of ulcerative colitis and can precipitate exacerbations. [23]

-

Smoking is negatively associated with ulcerative colitis (although some evidence appears to show it having a protective effect [10] ). This relationship is reversed in Crohn disease.

-

Milk consumption may exacerbate the disease.

Epidemiology

United States statistics

In the United States, about 1 million people are affected with ulcerative colitis (UC). [27, 28] The annual incidence is 10.4-12 cases per 100,000 people, and the prevalence rate is 35-100 cases per 100,000 people. Ulcerative colitis is three times more common than Crohn disease.

Ulcerative colitis occurs more frequently in white persons than in black persons or Hispanics. The incidence of ulcerative colitis is reported to be 2-4 times higher in Ashkenazi Jews. However, population studies in North America do not completely support this assertion.

Ulcerative colitis is slightly more common in women than in men. The age of onset follows a bimodal pattern, with a peak at 15-25 years and a smaller one at 55-65 years, although the disease can occur in people of any age. [29] Ulcerative colitis is uncommon in those younger than 10 years. Two of every 100,000 children are affected; however, 20%-25% of all cases of ulcerative colitis occur in persons aged 20 years or younger.

International statistics

Ulcerative colitis is more common in the Western and Northern hemispheres; the incidence is low in Asia and the Far East. [4]

In Japan, there are more than 160,000 patients with ulcerative colitis (about 27 per 100,000 people) and, unlike Western nations, a male predominance exists. [10]

Prognosis

In a systematic review and meta-analysis to evaluate patient-reported outcomes for rectal bleeding and stool frequency in 2132 patients with ulcerative colitis (UC) in endoscopic remission, investigators noted that most of these individuals who had normal rectal bleeding and stool frequency subscores attained endoscopic remission, although many had no rectal bleeding. [30] However, despite endoscopic remission, many patients had abnormal stool frequencies.

Ulcerative colitis may result in disease-related mortality. However, overall mortality is not increased in patients with ulcerative colitis, as compared to the general population. An increase in mortality may be observed among elderly patients with the disease. Mortality is also increased in patients who develop complications (eg, shock, malnutrition, anemia). Evidence suggests that mortality is increased in patients with ulcerative colitis who undergo any form of medical or surgical intervention.

Involvement of the muscularis propria in the most severe cases can lead to damage to the nerve plexus, resulting in colonic dysmotility, dilatation, and eventual infarction and gangrene. This condition is termed toxic megacolon and is characterized by a thin-walled, large, dilated colon that may eventually become perforated. Chronic ulcerative colitis is associated with pseudopolyp formation in about 15%-20% of cases. Chronic and severe cases can be associated with areas of precancerous changes, such as carcinoma in situ or dysplasia.

The most common cause of death of patients with ulcerative colitis is toxic megacolon. Colonic adenocarcinoma develops in 3%-5% of patients with ulcerative colitis, and the risk increases as the duration of disease increases. Patients with extensive ulcerative colitis over a long period have a significantly increased risk of colorectal cancer. [10] The risk of colonic malignancy is higher in cases of pancolitis and in cases in which disease onset occurs before age 15 years. Benign stricture rarely causes intestinal obstruction.

-

Ulcerative Colitis. Increased postrectal space is a known feature of ulcerative colitis.

-

Ulcerative Colitis. Plain abdominal radiograph from a patient with known ulcerative colitis who presented with an acute exacerbation of his symptoms. The image shows thumbprinting in the region of the splenic flexure of the colon.

-

Ulcerative Colitis. Double-contrast barium enema study shows pseudopolyposis of the descending colon.

-

Ulcerative Colitis. Single-contrast enema study in a patient with known ulcerative colitis in remission shows a benign stricture of the sigmoid colon.

-

Ulcerative Colitis. Plain abdominal radiograph in a 26-year-old with a 10-year history of ulcerative colitis shows a long stricture/spasm of the ascending colon/cecum. Note the pseudopolyposis in the descending colon.

-

Ulcerative Colitis. Single-contrast enema study in a patient with total colitis shows mucosal ulcers with a variety of shapes, including collar-button ulcers (yellow arrow), in which undermining of the ulcers occurs, and double-tracking ulcers (red arrow), in which the ulcers are longitudinally orientated.

-

Ulcerative Colitis. Double-contrast barium enema study shows total colitis. Note the granular mucosa in the cecum/ascending colon and multiple strictures in the transverse and descending colon in a patient with a more than a 20-year history of ulcerative colitis.

-

Ulcerative Colitis. Single-contrast barium enema study shows burnt-out ulcerative colitis.

-

Ulcerative Colitis. Intravenous urogram in the same patient as in Image 11 shows features of ankylosing spondylitis.

-

Ulcerative Colitis. Lateral radiograph of the lumbar spine in the same patient as in Images 10-11 shows a bamboo spine.

-

Ulcerative Colitis. Single-contrast barium enema study in a patient with Shigella colitis.

-

Ulcerative Colitis. Postevacuation image obtained after a single-contrast barium enema study shows extensive mucosal ulceration resulting from Shigella colitis.

-

Ulcerative Colitis. Double-contrast barium enema studies show granular mucosa associated with Campylobacter colitis.

-

Ulcerative Colitis. Ulcerative colitis as visualized with a colonoscope.

-

Ulcerative Colitis. Inflamed colonic mucosa demonstrating pseudopolyps.

Tables

What would you like to print?

- Overview

- Presentation

- DDx

- Workup

- Treatment

- Guidelines

- Guidelines Summary

- European Crohn's and Colitis Organisation (2022)

- Ulcerative Colitis Clinical Practice Guidelines (ASCRS, 2021)

- WSES-AAST Inflammatory Bowel Disease Emergency Management Clinical Practice Guidelines (2021)

- ECCO Clinical Practice Guidelines on Infections in Inflammatory Bowel Disease (2021)

- American Gastroenterological Association Guidelines (2020)

- American Gastroenterological Association Guidelines (2019)

- American College of Gastroenterology Guidelines (2019)

- British Society of Gastroenterology Guidelines (2019)

- Show All

- Medication

- Questions & Answers

- Media Gallery

- Tables

- References