Practice Essentials

Trench fever is a clinical syndrome caused by infection with Bartonella quintana; the condition was first described during World War I. Contemporary B quintana disease, commonly referred to as urban trench fever, is typically found in homeless, alcoholic, and poor populations.

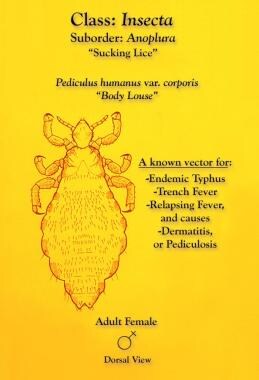

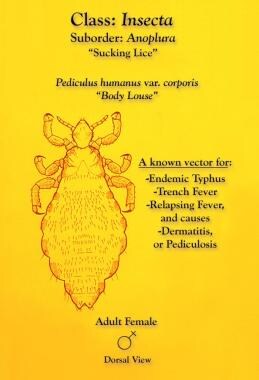

The human body louse Pediculus humanus var corporis is the major vector involved in trench fever transmission [1, 2] (see the image below).

Dorsal view of female body louse, Pediculus humanus var corporis. This louse is a known vector responsible for transmission of epidemic typhus, trench fever, and Asiatic relapsing fever; it also causes dermatitic condition known as pediculosis. Image courtesy of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Dorsal view of female body louse, Pediculus humanus var corporis. This louse is a known vector responsible for transmission of epidemic typhus, trench fever, and Asiatic relapsing fever; it also causes dermatitic condition known as pediculosis. Image courtesy of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Signs and symptoms

Classic symptoms of trench fever include the following:

-

Clinical incubation period of 3-48 days

-

Acute-onset fever in any of 3 distinct patterns, all of which are often associated with chills and diaphoresis: Abortive, relapsing (the most common pattern), or continuous

-

Acute-onset frontal or retro-orbital headache, often associated with a stiff neck and photophobia

-

Neuropsychiatric symptoms, such as weakness, depression, restlessness, and insomnia

-

Conjunctivitis

-

Dyspnea

-

Diffuse abdominal pain, often associated with anorexia, nausea, vomiting, weight loss, diarrhea, and constipation

-

Bone pain, particularly involving the shins; loin pain

-

Erythematous, macular rash

Urban trench fever typically includes 1 or more of these symptoms, but the presentation tends to be more variable.

Three additional syndromes are associated with B quintana infection, as follows:

-

Chronic lymphadenopathy – Enlarged cervical lymph nodes, without fever or other associated symptoms

-

Bacillary angiomatosis – characteristic skin lesions, with or without regional lymphadenopathy

-

B quintana endocarditis – Fever, new murmur, and heart failure; embolic phenomena

Characteristics of classic trench fever were fairly consistent, as follows:

-

Fever up to 104°F

-

Toxic initial appearance associated with prostration

-

Characteristic blanching, erythematous, macular rash

-

Conjunctivitis at the onset of illness

-

Paroxysmal tachycardia, paralleling the fever and exacerbated with exercise

-

Splenomegaly in more prolonged courses

-

Bone and muscle tenderness

-

Loss of Achilles reflex

-

Associated lice infestation

Physical findings of urban trench fever are more variable, but tend to include the following:

-

Presence of rash, fever, conjunctivitis, bone tenderness, splenomegaly, and neuropsychiatric signs vary, and the characteristic signs are generally less prevalent than in the classic cases

-

Nonspecific findings such as weight loss and weakness

Common findings in associated syndromes of urban trench fever are as follows:

-

Chronic lymphadenopathy – Lymphatic involvement of the cervical and mediastinal lymph nodes; afebrile and otherwise asymptomatic

-

Bacillary angiomatosis (immunocompetent) – Presence of one or more papules that progress to nodules that may be localized or disseminated; associated regional adenopathy; afebrile

-

Bacillary angiomatosis (immunocompromised) – Lesions are generally more widespread and are more likely to involve visceral organs than in the immunocompetent patient

-

B quintana endocarditis – Fever and murmur; typically involves the left-sided heart valves; embolic events; possible heart failure

Many patients with microbiologic or serologic evidence of B quintana infection are asymptomatic.

See Presentation for more details.

Diagnosis

B quintana infection is difficult to diagnose in the laboratory. The following studies may be useful:

-

Blood cultures

-

Immunofluorescent assays (IFAs) for immunoglobulin M (IgM) and immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibody levels for both B quintana and Bartonella henselae

-

Enzyme immunoassay (EIA) and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

-

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR)–based genomic assays and histochemical stains for direct detection of Bartonella DNA in both tissue and blood

-

Biopsy of skin, lymph node, cardiac valve, or other tissue

-

Metagenomic analysis via next-generation sequencing on infected tissue may have some value in identifying causes of culture-negative infective endocarditis by B quintana. [3]

See Workup for more details.

Management

Current antibiotic recommendations for each of the identified clinical syndromes associated with B quintana in immunocompetent patients are as follows:

-

Trench fever/urban trench fever – Doxycycline 100 mg PO twice daily for 28 days plus gentamicin 3 mg/kg/day IV for 14 days; macrolides and ceftriaxone are also effective

-

Chronic B quintana bacteremia – Doxycycline 100 mg PO twice daily for 28 days and gentamicin 3 mg/kg/day IV for 14 days; in some cases, longer therapy (up to 4 years) may be required; serial cultures demonstrating eradication of the bacteremia are pivotal in determining duration of therapy

-

Chronic lymphadenopathy – Erythromycin 500 mg PO 4 times daily for 3 months (first-line therapy) or doxycycline 100 mg PO twice daily for 3 months (alternative); in difficult cases, gentamicin 3 mg/kg/day IV for 14 days can be added

-

Bacillary angiomatosis – Erythromycin 500 mg PO 4 times daily for 3 months (first-line therapy) or doxycycline 100 mg PO twice daily for 3 months (alternative); in refractory cases, gentamicin 3 mg/kg/day IV for 14 days can be added; fluoroquinolones and ceftriaxone may also be considered

-

B quintana endocarditis – Doxycycline 100 mg PO twice daily for 6 weeks plus gentamicin 3 mg/kg/day IV for 14 days; if culture results are negative, ceftriaxone should be added

Valve replacement surgery is required in most cases of B quintana endocarditis.

See Treatment and Medication for more details.

Background

Trench fever is a clinical syndrome caused by infection with Bartonella quintana. The condition was first described during World War I, when it affected nearly 1 million soldiers. [4, 5, 1, 2] It has been known by several different names, including quintan fever, 5-day fever, shin bone fever, tibialgic fever, Wolhynia fever, and His-Werner disease.

DNA studies have demonstrated that many soldiers in Napoleon’s Grand Army at Vilnius in the 19th century were infected with B quintana. In addition, B quintana DNA was found in a 4000-year-old human tooth in Roaix, France. [6, 7] Reports of trench fever outbreaks stopped after World War I and then reappeared transiently on the Eastern Front in Europe during World War II.

By the end of World War I, the human body louse Pediculus humanus was recognized as the likely vector for trench fever transmission. [1, 2] Rickettsia -like organisms in the body and feces of P humanus were postulated to be the cause. In 1969, Vinson et al successfully cultivated the causative organism (then called Rickettsia quintana) from a sick patient and reproduced the disease by inoculating healthy volunteers. [8] The organism was briefly placed in the genus Rochalimaea before being reclassified as Bartonella quintana in 1993.

During World War I, trench fever was characterized by the abrupt onset of fever, malaise, myalgias, headache, transient macular rashes of the torso, pain in the long bones of the leg (shins), and splenomegaly. [9, 10, 1, 2, 4, 5, 11, 12] Typical periodic cycles of fever, chills, and sweats occurred at 5-day intervals, resulting in prolonged disability lasting 3 months or longer in young soldiers. However, no deaths attributable to trench fever have ever been reported.

Over the past 3 decades, Bartonella species have emerged as a cause of bacteremia, angioproliferative disease (eg, bacillary angiomatosis), and endocarditis in patients with and without HIV infection. In 1995, B quintana was found to cause bacteremia in 10 homeless, HIV-negative alcoholics. [13] In 1999, B quintana endocarditis was described in 3 HIV-negative homeless alcoholic men. [14] These cases suggest that B quintana disease is not limited to wartime outbreaks or immunocompromised persons.

Subsequently, sporadic cases and small clusters of B quintana infection have been described worldwide and appear to be associated with poor sanitation, poor hygiene, alcoholism, and malnutrition—all of which are commonly seen in both classic and urban trench fever cases. Seroprevalence studies suggest that B quintana infection is more common than is clinically recognized and that many infections are subclinical.

The term urban trench fever is applied to contemporary B quintana disease. Urban trench fever is typically found in homeless, alcoholic, and poverty-stricken populations, among whom poor personal hygiene is common. The infection affects both immunocompetent and immunocompromised persons. Some (but not all) persons with urban trench fever have evidence of louse infestation.

The spectrum of disease associated with B quintana infection includes asymptomatic infection, urban trench fever, angioproliferative disease, chronic lymphadenopathy, bacteremia, and endocarditis. [10, 15, 16]

Pathophysiology

The human body louse P humanus var corporis is the major vector involved in trench fever transmission (see the image below). [1, 2]

Dorsal view of female body louse, Pediculus humanus var corporis. This louse is a known vector responsible for transmission of epidemic typhus, trench fever, and Asiatic relapsing fever; it also causes dermatitic condition known as pediculosis. Image courtesy of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Dorsal view of female body louse, Pediculus humanus var corporis. This louse is a known vector responsible for transmission of epidemic typhus, trench fever, and Asiatic relapsing fever; it also causes dermatitic condition known as pediculosis. Image courtesy of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

After B quintana is introduced into the human body, it invades erythrocytes and endothelial cells, where it is protected from the host’s humoral immune response. [17] Intraerythrocytic B quintana colonization is largely limited to human beings, [10, 15] while the invasion of vascular endothelial cells is less species-specific. [18] Monocytes from homeless individuals with chronic B quintana bacteremia have been shown to overproduce interleukin (IL)–10, resulting in an attenuated immune response that may facilitate the bacterial persistence. [19] These same patients generate a poorer humoral response than patients with endocarditis, in whom the inflammatory response is more dramatic and bacteremia less frequent. [20]

Once the organism invades and begins to multiply within endothelial cells, proinflammatory cytokines are activated, apoptosis suppressed, and vascular proliferation initiated. [21] These changes result in systemic symptoms, bacteremia, endovascular infection, and lymphatic enlargement. The relationship between the endothelial vascular proliferation and the destructive valvular lesions of B quintana endocarditis is unknown. A potential connection might be the presence of variably expressed outer-membrane proteins in some strains of B quintana. These proteins induce secretion of vascular endothelial growth factor and are associated with increased rates of invasion. [22]

Despite this possible immunologic association, the histologic features of these two clinical variants differ. [10] The pathogenesis of B quintana –associated disease suggests that bacteremia is an early occurrence common to all of the various syndromes attributed to it. In some patients, the bacteremia lasts for a few days, whereas, in others, it lasts for months to years. [15]

Etiology

B quintana causes both trench fever and urban trench fever. [10, 8] Humans are the predominant reservoir of the pathogen, although infection has been documented in some nonhuman primates and in cats. [23, 24, 25, 26] In infected persons, the organisms can be found in human blood, tissues (particularly skin), and urine. [10]

B quintana bacteremia may be intermittent or prolonged for years, suggesting that blood-sucking arthropods are efficient transmitters of B quintana infection. [17, 15] External parasitic infestations are also associated with conditions of squalor. Although the body louse P humanus is the major vector for both trench fever and urban trench fever, its presence is not always demonstrated in patients with urban trench fever. [8, 14, 27]

Breaks in the skin contaminated by louse feces and arthropod bites are documented portals of entry. Other possible vectors include mites, ticks, and fleas. [10] A 2014 study showed that cat fleas (Ctenocephalides felis) can ingest B quintana and release viable bacteria into their feces. [28] Contamination of mucous membranes, transfusion, transplantation, and IV drug abuse are also potential avenues of entry. Human-to-human transmission of trench fever has not been described.

Epidemiology

Predisposing factors for B quintana infection include war, famine, malnutrition, homelessness, alcoholism, intravenous (IV) drug abuse, and poor hygiene.

United States statistics

B quintana was found in the lice of 33.3% of body lice–infested and 25% of head lice–infested homeless persons in California. [29] In one study, 20% of the patients in a downtown Seattle clinic that serves a homeless indigent population had microimmunofluorescent antibody titers of 1:64 or greater to Bartonella species. [30] Multivariate analysis of these patients revealed that alcohol abuse was the only independent variable associated with seropositivity. It is difficult, however, to ascertain the true incidence of urban trench fever, as most infected individuals are asymptomatic. Moreover, the disease occurs sporadically and in small clusters of homeless persons.

International statistics

B quintana–related illness has been found on every continent except Antarctica. Well-performed seroprevalence studies have identified patients with B quintana antibodies in France, Greece, Sweden, Japan, Brazil, Croatia, and Peru. [20, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36] Cases of culture-negative endocarditis with antibody titers positive for B quintana have been reported in Europe, Australia, Japan, Tunisia, and India. [37, 38, 39, 40, 41]

Age-, sex-, and race-related demographics

Whereas trench fever described during wartime typically affected young soldiers, urban trench fever typically affects middle-aged adults. Rare cases of Bartonella endocarditis and central nervous system (CNS) infection have been described in children.

Because trench fever was historically an infection of soldiers, most of the cases documented during World Wars I and II were in males. Cases of urban trench fever described since 1995 have also predominantly involved males, reflecting the disproportionate representation of males in the homeless alcoholic population.

No convincing data suggest that urban trench fever or other syndromes caused by B quintana infection have a racial or ethnic predilection.

Prognosis

In most immunocompetent hosts, B quintana infection is self-limited unless endocarditis occurs. In immunocompromised hosts, however, B quintana infection tends to be more severe and may result in death.

During World War I, trench fever resulted in significant morbidity and prolonged disability but no recognized mortality. Contemporary descriptions of B quintana endocarditis in homeless alcoholic males have found mortality rate to be as high as 12%, with most deaths related to complications of endocarditis or to the surgery used in its treatment. [42, 43]

Patient Education

Patients should be educated about practicing good personal hygiene and improving their living conditions. Vector control of the body louse should also be explained.

-

Dorsal view of female body louse, Pediculus humanus var corporis. This louse is a known vector responsible for transmission of epidemic typhus, trench fever, and Asiatic relapsing fever; it also causes dermatitic condition known as pediculosis. Image courtesy of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.