Practice Essentials

Testicular seminoma (see the image below) is a pathologic diagnosis in which only seminomatous elements are observed upon histopathologic review after a radical orchiectomy and in which the serum alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) level is within the reference range. Testicular cancer, although rare, is the most common malignancy in men aged 20-34 years; 95% of malignant tumors arising in the testes are germ cell tumors (GCTs), and seminomas are the most common type of testicular GCTs. [1] The risk of testis cancer is 10-40 times higher in patients with a history of cryptorchidism; 10% of patients with GCTs have a history of cryptorchidism. [2]

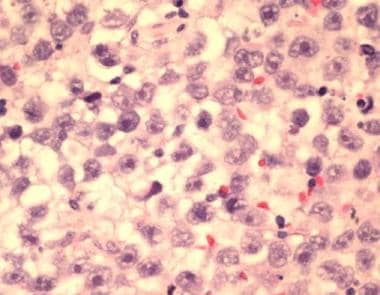

This is a classic testicular seminoma, high-power view, from a 37-year-old man with a painless mass in his right testis. Levels of serum beta-human chorionic gonadotropin and alpha-fetoprotein were within the reference range, and the metastatic workup findings were negative. Histopathology showed a pure seminoma. Metastatic workup showed no nodal or distant spread, T1N0M0 stage I. After orchiectomy, the patient underwent adjuvant external beam radiotherapy to the para-aortic nodes. At a 3-year follow-up study, the patient is disease free and has a greater than 95% chance of remaining disease free. See related image for a scrotal sonogram of this patient. Note here that tumor cells are uniform, have abundant clear cytoplasm, a large centrally located nucleus, and a variable mitotic pattern.

This is a classic testicular seminoma, high-power view, from a 37-year-old man with a painless mass in his right testis. Levels of serum beta-human chorionic gonadotropin and alpha-fetoprotein were within the reference range, and the metastatic workup findings were negative. Histopathology showed a pure seminoma. Metastatic workup showed no nodal or distant spread, T1N0M0 stage I. After orchiectomy, the patient underwent adjuvant external beam radiotherapy to the para-aortic nodes. At a 3-year follow-up study, the patient is disease free and has a greater than 95% chance of remaining disease free. See related image for a scrotal sonogram of this patient. Note here that tumor cells are uniform, have abundant clear cytoplasm, a large centrally located nucleus, and a variable mitotic pattern.

Signs and symptoms

The typical presentation in testicular seminoma is as follows:

-

A male aged 15-35 years presents with a painless testicular lump that has been noticeable for several days to months

-

Patients commonly have abnormal findings on semen analysis at presentation, and they may be subfertile [3]

-

Patients may present with a hydrocele, and scrotal ultrasonography may identify a nonpalpable testis tumor

Uncommon presentations include the following:

-

Testicular pain, possibly with an acute onset; may be associated with a hydrocele

-

A metastatic testis tumor may manifest as large retroperitoneal and/or chest lesions, while the primary tumor is nonpalpable

See Presentation for more detail.

Diagnosis

Laboratory studies for testicular seminoma are as follows:

-

An elevated AFP level rules out pure seminoma, despite possible contrary histopathologic orchiectomy findings

-

Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) is a less-specific marker for GCTs, but levels can correlate with overall tumor burden

-

Beta–human chorionic gonadotropin (beta-hCG) levels are elevated inn 5-10% of patients with seminomas; elevation may correlate with metastatic disease but not with overall survival

-

Placenta-like alkaline phosphatase levels can be elevated in patients with seminoma, especially as the tumor burden increases; however, those levels may also increase with smoking

Scrotal ultrasonography

-

Consider this study in any male with a palpable testicular mass that is suspicious or questionable.

-

Other indications may include acute scrotal pain (especially when associated with a hydrocele), nonspecific scrotal pain, or swelling.

-

If an asymptomatic hydrocele obscures physical examination of the testicle, this study may be appropriate prior to surgical intervention.

-

This study may also be appropriate for males who are at the peak age range for testicular cancer (ie, 15-35 years).

-

Scrotal ultrasonography commonly shows a homogeneous hypoechoic intratesticular mass.

-

Larger lesions may be more inhomogeneous.

-

Calcifications and cystic areas are less common in seminomas than in nonseminomatous tumors.

Other imaging studies

-

Abdominal and pelvic CT scanning: Can be used to identify metastatic disease to the retroperitoneal lymph nodes, but results in understaging in approximately 15-20% of patients thought to be at stage I [4]

-

Chest CT scanning: Indicated only when abnormal findings are observed on a chest radiograph

-

Fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) PET scanning: May be useful in restaging assessments of residual masses following chemotherapy

Histologic findings

Seminomas can have 3 histologic variants, as follows [5] :

-

Classic seminoma (the most common histologic type)

-

Anaplastic seminoma (5-15% of patients)

-

Spermatocytic seminoma (a rare variant that occurs in older adults)

See Workup for more detail.

Management

In testicular seminoma, orchiectomy provides both diagnosis and therapy. Orchiectomy alone cures most stage I seminomas. To prevent relapse, the following are standard options in stage I disease [1] :

-

Surveillance

-

Single-agent carboplatin

-

Radiotherapy

Preferred treatments for more advanced stages are as follows [1] :

-

Stage IIA - Radiotherapy or chemotherapy with etoposide and cisplatin (EP) or bleomycin, etoposide, and cisplatin (BEP)

-

Stage IIB - Chemotherapy with EP or BEP (preferred) or radiotherapy

-

Stage IIC, III (good risk) - Chemotherapy with EP or BEP

-

Stage IIC, III (high risk) - Chemotherapy with EP or etoposide, mesna, ifosfamide and cisplatin (VIP)

After treatment, patients require lifelong follow-up. Surveillance includes the following, with the frequency determined by disease stage and duration of follow-up:

-

History and physical examination

-

Serum tumor markers (beta-hCG, LDH, AFP)

-

Chest radiography

-

CT scan of the abdomen, with or without CT scan of the pelvis

See Treatment and Medication for more detail.

For patient education information, see Testicular Cancer and Testicular Self-Exam.

Background

The study of testicular germ cell tumors (GCTs) is a unique area of urologic oncology, as treatment algorithms have benefited from numerous randomized prospective clinical trials (unlike prostate cancer) and because metastatic disease is highly responsive to multimodal treatment (unlike renal cell carcinoma). Seminoma is a histologic subtype of GCTs, which are discussed separately as nonseminomas in Germ Cell Tumors.

The interest in GCTs is disproportional to its incidence because of its fascinating pathologic subtypes, success of multimodal therapy (even for metastatic disease), and almost universal incidence in otherwise healthy males aged 15-35 years. Testicular GCTs have various pathologic subtypes, including seminoma, embryonal, yolk sac, teratoma, and choriocarcinoma. The most important clinical distinction is between seminoma and nonseminoma, two broad categories with different treatment algorithms: (1) Seminoma as a classification refers to pure seminoma upon histopathologic review, and (2) the presence of any nonseminomatous elements (even if seminoma is prevalent) changes the classification to nonseminoma.

Pathophysiology

Testicular seminoma is a pathologic diagnosis in which only seminomatous elements are observed upon histopathologic review after a radical orchiectomy and in which serum alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) is within the reference range. Any elevation of AFP levels or nonseminomatous elements in the testis specimen mandates diagnosis of nonseminomatous GCT (NSGCT) and an appropriate treatment change.

GCTs have the following subtypes and frequencies: seminoma (40%), embryonal (25%), teratocarcinoma (25%), teratoma (5%), and choriocarcinoma (pure; 1%). Seminomas can be further subdivided into one of three categories based on histology: classic, anaplastic, and spermatocytic (see Workup/Histologic Findings). [5]

Germ cell carcinoma in situ (CIS) is a premalignant condition with a natural history of progression to seminoma or embryonal cancer. Patients with infertility, intersex disorders, cryptorchidism, prior contralateral GCTs, or atrophic testes more commonly have CIS. Histologically, it demonstrates intratubular atypical germ cells within seminiferous tubules. Most patients with seminomas (except spermatocytic seminoma) and NSGCTs have CIS or severe atypia associated with the primary tumor. [6] In patients with GCTs, 5% of those with contralateral testes harbor CIS. [7]

Testicular microcalcifications observed on scrotal sonograms were long held to be implicated in the development of testicular carcinoma. However, an analysis of 83 patients with asymptomatic microcalcifications observed for 5 years demonstrated only one with testicular carcinoma development over the interim. This represented an odds ratio for the study population of 317 (95% CI, 36-2756), with over 98% of men with asymptomatic microcalcifications having a benign course. A recommendation of continued monthly self-examination without further intervention was given for management of this indolent finding. [8]

Etiology

Risk of testis cancer is 10 to 40 times higher in patients with a history of cryptorchidism; 10% of patients with germ cell tumors (GCTs) have a history of cryptorchidism. [2] Risk is greater for the abdominal versus inguinal location of undescended testis. An abdominal testis is more likely to be seminoma, while a testis surgically brought to the scrotum by orchiopexy is more likely to be a nonseminomatous SGCT. Orchiopexy allows for earlier detection by physical examination but does not alter the risk of GCT.

Other risk factors include trauma, mumps, and maternal estrogen exposure. Hemminki and colleagues demonstrated a familial risk for testicular cancer, with a 4-fold increased risk in a male with a father who had a GCT and a 9-fold increased risk if a brother was affected. [9]

Environmental exposures including organochlorines, polychlorinated biphenyls, polyvinyl chlorides, phthalates, marijuana, and tobacco have been shown to increase the incidence of testicular cancer. [10]

Genetic changes in the form of amplifications and deletions are observed mainly in the 12p11.2-p12.1 chromosomal regions. [11] A gain of 12p sequences is associated with invasive growth of both seminomas and NSGCTs. In contrast, spermatocytic seminoma shows a gain of chromosome 9, while most infantile yolk sac tumors and teratomas show no chromosomal changes.

Somatic mutations of the KIT gene occur in approximately 5% of all testicular GCTs. Of these, Coffey and colleagues (2008) demonstrated that only seminomas contain activating mutations of the KIT gene. [12]

Epidemiology

United States

Testicular cancer is relatively uncommon and accounts for < 1% of all male tumors. The American Cancer Society estimates that approximately 9190 new cases of testicular cancer will be diagnosed in 2023, but only 470 men will die of the disease. [13] In the United States, testicular seminoma is the most common subtype of testicular cancer, accounting for 55% of cases. [10]

International

The incidence of testis cancer increased from the early 1960s to the mid 1980s. Nonwhite populations have a lower incidence than white populations. The highest rates of testis cancer are in Denmark (11.5 cases per 100,000 persons per year), Norway (9 cases per 100,000 persons per year), and Switzerland (11 cases per 100,000 persons per year). Rates vary across Europe. [14]

A review by Bray and colleagues (2006) of 41 cancer registries in 14 countries found the seminoma rates to be highest in Denmark and Switzerland (9 cases per 100,000 persons per year) and the lowest rates in Japan, Israel, and Finland (1-3 cases per 100,000 persons per year). [15]

Race- and Age-related Demographics

Established data sets have consistently demonstrated a higher incidence of GCTs in whites than in African Americans—as high as a 5:1 ratio. A 2005 analysis by McGlynn et al of 9 registries of the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database from 1973-2001 found an increasing incidence among African Americans starting in the 1990s. The increased incidence was 100% for GCTs overall—124% for seminoma and 64% for nonseminoma. The reasons for this increase are unclear, and the authors' review of the data suggests environmental or nonperinatal factors (occupation, physical activity, diet) rather than early screening as the predominant cause. [16]

A study using data from the SEER program and the National Program of Cancer Registries found that rates of seminoma changed little between 1999 and 2012. These authors forecast that seminoma rates will decrease in Black, White, and Asian/Pacific Islander men, but will increase in Hispanic men, equaling rates in White men by 2026. [17]

Testicular GCTs represent the most common malignancy in men aged 20-34 years. [1]

Prognosis

Mortality rates from testicular seminomas increased until the 1970s but have since declined greatly as a result of advances in treatment. Currently, all stages have at least a 90% cure rate. [18]

In a review of testicular GCT patients diagnosed in Norway from 1953-2012, Kvammen et al found that although relative survival has improved in recent decades, it generally continues to decline with increasing follow-up time, particularly beyond 15-30 years, regardless of disease extent at diagnosis. Relative survival was lower in patients diagnosed before 1980 or after age 40. These authors proposed that the likely main cause is treatment-induced late effects, with the continued use of adjuvant radiotherapy in seminomas until the year 2000 as the suspected culprit. [19]

Cure rates by stage are as follows:

-

Stage I: 98%-100%

-

Stage II (B1/B2 nonbulky): 98%-100%

-

Stage II (B3 bulky) and stage III: 90% complete response to chemotherapy and 86% durable response rate to chemotherapy.

Treatment-related disease in long-term survivors

Patients with testicular cancer are at an increased risk of secondary cancers because of their young age at diagnosis, high cure rate, and exposure to radiation, chemotherapy, or both. In a study of a cohort of 14 population-based tumor registries in Europe and North America totaling 40,576 patients, Travis et al reported that survivors of testicular cancer are at a significantly increased risk of solid tumors for at least 35 years after treatment. [20]

Tumors included malignant mesothelioma and those of the lung, colon, bladder, pancreas, and stomach. The relative risk increases were the same for seminoma and nonseminoma, and with treatment with radiation, chemotherapy, or both. For patients diagnosed with seminoma at age 35 years, the cumulative risk 40 years later was 36%, compared with 23% for the general population. [20]

Zagars et al reported on long-term follow-up involving 477 men with low-stage seminoma treated with orchiectomy and adjuvant radiation at a single institution. They compared long-term cancer-specific survival with cardiac-specific survival and performed a risk analysis in relation to standard US data for males. No differences were seen in the first 15 years, but, after 15 years, the relative risk of secondary cancer deaths was increased. [21]

In summary, these two long-term follow-up studies demonstrate that, although many men with seminoma are cured, they require counseling and long-term follow-up to minimize the risk of excess mortality from secondary cancers.

Increased risk for cardiac disease has also been observed in seminoma survivors. [20, 1] However, a population-based study in 9193 patients with stage I testicular seminoma by Beard et al found no increase in deaths from cardiovascular disease after radiotherapy. Deaths from second malignant neoplasms were elevated, but at a rate considerably lower than reported in historical series. [22]

-

Testicular seminoma. A 57-year-old man presents with abdominal pain of slow onset. CT scanning shows a large 25-cm retroperitoneal lesion encompassing the aorta and renal vasculature and displacing the right kidney laterally. The patient had a history of cryptorchidism repaired at age 8 years. Testes were normal and descended; however, ultrasonography showed a small 5-mm lesion on the right testis, which proved to be pure seminoma at orchiectomy. The beta-human chorionic gonadotropin level was 70 mIU/mL (reference range, < 5 mIU/mL), and the alpha-fetoprotein level was within the reference range; no metastatic lesions were observed above the diaphragm, indicating stage IIb (bulky), T1N3M0. The patient was referred for 4 cycles of cisplatin-based chemotherapy.

-

Testicular seminoma. This scrotal ultrasound of a 37-year-old man with a painless mass in his right testis shows a right testis with hypoechoic solid masses compared to the homogeneous, more hyperechoic, healthy left testis. Levels of serum beta-human chorionic gonadotropin and alpha-fetoprotein were within the reference range, and the metastatic workup findings were negative. Histopathology showed a pure seminoma. Metastatic workup showed no nodal or distant spread, T1N0M0 stage I. After orchiectomy, the patient underwent adjuvant external beam radiotherapy to the para-aortic nodes. At a 3-year follow-up study, the patient is disease free and has a greater than 95% chance of remaining disease free.

-

Testicular seminoma. This is a classic seminoma at low power. Uniform tumor cells are observed with mild inflammatory response (lymphocytes). Other seminoma findings not seen could include a fibrovascular stroma, syncytiotrophoblastic cells, and multinucleated histiocytes.

-

This is a classic testicular seminoma, high-power view, from a 37-year-old man with a painless mass in his right testis. Levels of serum beta-human chorionic gonadotropin and alpha-fetoprotein were within the reference range, and the metastatic workup findings were negative. Histopathology showed a pure seminoma. Metastatic workup showed no nodal or distant spread, T1N0M0 stage I. After orchiectomy, the patient underwent adjuvant external beam radiotherapy to the para-aortic nodes. At a 3-year follow-up study, the patient is disease free and has a greater than 95% chance of remaining disease free. See related image for a scrotal sonogram of this patient. Note here that tumor cells are uniform, have abundant clear cytoplasm, a large centrally located nucleus, and a variable mitotic pattern.