Background

Infection with Streptococcus pyogenes, a beta-hemolytic bacterium that belongs to Lancefield serogroup A, also known as the group A streptococci (GAS), causes a wide variety of diseases in humans. A ubiquitous organism, S pyogenes is the most common bacterial cause of acute pharyngitis, accounting for 15-30% of cases in children and 5-10% of cases in adults. [1] During the winter and spring in temperate climates, up to 20% of asymptomatic school-aged children may be group A streptococcus carriers. [2, 3]

An understanding of the diverse nature of infectious disease complications attributable to this organism is an important cornerstone of pediatric medicine. In addition to infections of the upper respiratory tract and the skin, S pyogenes can cause a wide variety of invasive systemic infections. Along with Staphylococcus aureus, group A streptococcus is one of the most common pathogens responsible for cellulitis. Infection with this pathogen is also causally linked to 2 potentially serious nonsuppurative complications: acute rheumatic fever (ARF) and acute glomerulonephritis. In addition, infection with S pyogenes has reemerged as an important cause of toxic shock syndrome (TSS) and of life-threatening skin and soft-tissue infections, especially necrotizing fasciitis.

Invasive soft tissue infection due to Streptococcus pyogenes. This child developed fever and soft-tissue swelling on the fifth day of a varicella-zoster infection. Leading edge aspirate of cellulitis grew S pyogenes. Although the patient responded to intravenous penicillin and clindamycin, operative débridement was necessary because of clinical suspicion of early necrotizing fasciitis.

Invasive soft tissue infection due to Streptococcus pyogenes. This child developed fever and soft-tissue swelling on the fifth day of a varicella-zoster infection. Leading edge aspirate of cellulitis grew S pyogenes. Although the patient responded to intravenous penicillin and clindamycin, operative débridement was necessary because of clinical suspicion of early necrotizing fasciitis.

Lancefield classification scheme

As originally described by Lancefield, beta-hemolytic streptococci can be divided into many groups based on the antigenic differences in group-specific polysaccharides located in the bacterial cell wall. More than 20 serologic groups have been identified and designated by letters (eg, A, B, C). Of the non–group A streptococci, group B is the most important human pathogen (the most common cause of neonatal sepsis and bacteremia), although other groups (particularly group G) have occasionally been implicated as causes of pharyngitis.

The emm classification scheme

The traditional Lancefield classification system, which is based on serotyping, has been replaced by emm typing, which has been used to characterize and measure the genetic diversity among isolates of S pyogenes. This system is based on a sequence at the 5' end of a locus (emm) that is present in all isolates. The targeted region of emm displays the highest level of sequence polymorphism known for an S pyogenes gene; more than 150 emm types have been described to date. [4] The emm gene encodes the M protein.

There are 4 major subfamilies of emm genes, which are defined by sequence differences within the 3' end, encoding the peptidoglycan-spanning domain. The chromosomal arrangement of emm subfamily genes reveals 5 major emm patterns, designated as emm patterns A through E. An example of the usefulness of emm typing is described by McGregor et al. [5]

Identification of GAS

Although serologic grouping by the Lancefield method is the criterion standard for differentiation of pathogenic streptococcal species, group A organisms can be identified more cost effectively by numerous latex agglutination, coagglutination, or enzyme immunoassay procedures.

Group A strains can also be distinguished from other groups by their sensitivity to bacitracin. A disc that contains 0.04U of bacitracin inhibits the growth of more than 95% of group A strains, whereas 80-90% of non–group A strains are resistant to this antibiotic. The bacitracin disc test is simple to perform and interpret in an office-based laboratory and is sufficiently accurate for presumptive identification of GAS.

Presumptive identification of a strain as a group A streptococcus can also be made on the basis of production of the enzyme L-pyrrolidonyl-beta-naphthylamide (PYRase). Among the beta-hemolytic streptococci isolated from throat culture, only group A isolates produce PYRase, which can be identified on the basis of the characteristic color change (red) after inoculation of a disk on an agar plate followed by overnight incubation.

When cultured on blood agar plates, the production of a characteristic zone of complete hemolysis (beta hemolysis) is another important clue to the classification of S pyogenes. (For example, Streptococcus pneumoniae generates a zone of only partial hemolysis [alpha hemolysis].)

Spectrum of diseases caused by group A streptococcal infections

In the preantibiotic era, streptococci frequently caused significant morbidity and were associated with significant mortality rates. However, in the postantibiotic period, diseases due to streptococcal infections are well-controlled and uncommonly cause death. GAS can cause a diverse variety of suppurative diseases and nonsuppurative postinfectious sequelae.

The suppurative spectrum of GAS diseases includes the following:

-

Pharyngitis - With or without tonsillopharyngeal cellulitis or abscess

-

Impetigo - Purulent, honey-colored, crusted skin lesions

-

Necrotizing fasciitis

-

Cellulitis

-

Streptococcal bacteremia

-

Sinusitis

-

Meningitis or brain abscess (a rare complication resulting from direct extension of an ear or sinus infection or from hematogenous spread)

The nonsuppurative sequelae of GAS infections include the following:

-

ARF - Defined by Jones criteria

-

Rheumatic heart disease - Chronic valvular damage, predominantly the mitral valve

A superantigen-mediated immune response may result in the development of scarlet fever or streptococcal TSS. Scarlet fever is characterized by an upper-body rash, generally following pharyngitis.

Streptococcal TSS is characterized by systemic shock with multiorgan failure, with manifestations that include respiratory failure, acute renal failure, hepatic failure, neurologic symptoms, hematologic abnormalities, and skin findings, among others. This is predominantly associated with M types 1 and 3 that produce pyrogenic exotoxin A, exotoxin B, or both. [6]

Pathophysiology

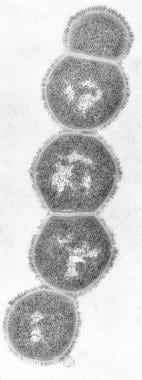

Streptococci are a large group of gram-positive, nonmotile, non–spore-forming cocci about 0.5-1.2µm in size. They often grow in pairs or chains and are negative for oxidase and catalase.

S pyogenes tends to colonize the upper respiratory tract and is highly virulent as it overcomes the host defense system. The most common forms of S pyogenes disease include respiratory and skin infections, with different strains usually responsible for each form.

The cell wall of S pyogenes is very complex and chemically diverse. The antigenic components of the cell are the virulence factors. The extracellular components responsible for the disease process include invasins and exotoxins. The outermost capsule is composed of hyaluronic acid, which has a chemical structure resembling host connective tissue, allowing the bacterium to escape recognition by the host as an offending agent. Thus, the bacterium escapes phagocytosis by neutrophils or macrophages, allowing it to colonize. Lipoteichoic acid and M proteins located on the cell membrane traverse through the cell wall and project outside the capsule.

Epithelial cell invasion

A characteristic of S pyogenes is the organism’s ability to invade epithelial cells. Failure of penicillin to eradicate S pyogenes from the throats of patients, especially those who are carriers of S pyogenes, has been increasingly reported. The results of one study strongly suggested that if the carrier state results from intraepithelial cell streptococci survival, the failure of penicillin to kill ingested S pyogenes may be related to a lack of effective penicillin entry into epithelial cells. [7] These observations may have clinical implications for understanding carriers and managing S pyogenes infection.

Bacterial virulence factors

The cell wall antigens include capsular polysaccharide (C-substance), peptidoglycan and lipoteichoic acid (LTA), R and T proteins, and various surface proteins, including M protein, fimbrial proteins, fibronectin-binding proteins (eg, protein F), and cell-bound streptokinase.

The C-substance is composed of a branched polymer of L-rhamnose and N -acetyl-D-glucosamine. It may have a role in increased invasive capacity. The R and T proteins are used as epidemiologic markers and have no known role in virulence. [8]

Another virulence factor, C5A peptidase, destroys the chemotactic signals by cleaving the complement component of C5A.

M protein, the major virulence factor, is a macromolecule incorporated in fimbriae present on the cell membrane projecting on the bacterial cell wall. It is the primary cause of antigenic shift and antigenic drift among GAS. [9, 10]

M protein binds the host fibrinogen and blocks the binding of complement to the underlying peptidoglycan. This allows survival of the organism by inhibiting phagocytosis. Strains that contain an abundance of M protein resist phagocytosis, multiply rapidly in human tissues, and initiate the disease process. After an acute infection, type-specific antibodies develop against M protein activity in some cases.

Although such antibodies protect against infection by a homologous M protein type, they confer no immunity against other M types. This observation is one of the factors representing a major theoretical obstacle to the S pyogenes vaccine design, because more than 80 M serotypes have been described to date.

Community-based outbreaks of particular streptococcal diseases tend to be associated with certain M types; therefore, M serotyping has been very valuable for epidemiologic studies.

Bacterial adherence factors

At least 11 different surface components of GAS have been suggested to play a role in adhesion. In 1997, Hasty and Courtney proposed that GAS express different arrays of adhesins in various environmental niches. Based on their review, M protein mediates adhesion to HEp-2 cells, but not to buccal cells, in humans, whereas FBP54 mediates adhesion to buccal cells, but not to HEp-2 cells. Protein F mediates adhesion to Langerhans cells, but not to keratinocytes.

One of the theories proposed with regard to the process of adhesion is a 2-step model. The initial step in overcoming the electrostatic repulsion of the bacteria from the host is mediated by LTA, which provides weak, reversible adhesion. The second step takes the form of firm, irreversible adhesion mediated by tissue-specific M protein, protein F, or FBP54, among others. Once adherence has occurred, the streptococci resist phagocytosis, proliferate, and begin to invade the local tissues. [11]

GAS show enormous and evolving molecular diversity, driven by horizontal transmission among various strains. This is also true when they are compared with other streptococci. Acquisition of prophages accounts for much of the diversity, conferring not only virulence via phage-associated virulence factors but also increased bacterial survival against host defenses.

Extracellular products and toxins

Various extracellular growth products and toxins produced by GAS are responsible for host cell damage and inflammatory response.

Hemolysins

S pyogenes elaborates 2 distinct hemolysins. These proteins are responsible for the zone of hemolysis observed on blood agar plates and are also important in the pathogenesis of tissue damage in the infected host. Streptolysin O is toxic to a wide variety of cell types, including myocardium, and is highly immunogenic. The determination of the antibody responses to this protein (antistreptolysin O [ASO] titer) is often useful in the serodiagnosis of recent infection.

Streptolysin S is another virulence factor capable of damaging polymorphonuclear leukocytes and subcellular organelles. However, in contrast to streptolysin O, it does not appear to be immunogenic.

Pyrogenic exotoxins

The family of streptococcal pyrogenic exotoxins (SPEs) includes SPEs A, B, C, and F. These toxins are responsible for the rash of scarlet fever. Other pathogenic effects caused by these substances include pyrogenicity, cytotoxicity, and enhancement of susceptibility to endotoxin. SPE B is a precursor of a cysteine protease, another determinant of virulence. [12]

Group A streptococcal isolates associated with streptococcal TSS encode certain SPEs (ie, A, C, F) capable of functioning as superantigens. These antigens induce a marked febrile response, induce proliferation of T lymphocytes, and induce synthesis and release of multiple cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor, interleukin-1 beta, and interleukin-6. This activity is attributed to the ability of the superantigen to simultaneously bind to the V-beta region of the T-cell receptor and to class II major histocompatibility antigens of antigen-presenting mononuclear cells, resulting in widespread, nonspecific T-cell proliferation and increased production of interleukin-2.

Nucleases

Four antigenically distinct nucleases (A, B, C, D) assist in the liquefaction of pus and help to generate substrate for growth.

Other products

Other extracellular products include NADase (leukotoxic), hyaluronidase (which digests host connective tissue, hyaluronic acid, and the organism's own capsule), streptokinases (proteolytic), and streptodornase A-D (deoxyribonuclease activity). [13]

Proteinase, amylase, and esterase are additional streptococcal virulence factors, although the role of these proteins in pathogenesis is not fully understood.

Suppurative disease spectrum

Streptococcal pharyngitis

S pyogenes causes up to 15-30% of cases of acute pharyngitis. [14] Frank disease occurs based on the degree of bacterial virulence after colonization of the upper respiratory tract. Accurate diagnosis is essential for appropriate antibiotic selection.

Impetigo

Pyoderma is the most common form of skin infection caused by GAS. Also referred to as streptococcal impetigo or impetigo contagiosa, it occurs most commonly in tropical climates but can be highly prevalent in northern climates as well, particularly in the summer months. Risk factors that predispose to this infection include low socioeconomic status; low level of overall hygiene; and local injury to skin caused by insect bites, scabies, atopic dermatitis, and minor trauma. Colonization of unbroken skin precedes the development of pyoderma by approximately 10 days.

Streptococcal pyoderma may occur in children belonging to certain population groups and in overcrowded institutions. The modes of transmission are direct contact, environmental contamination, and houseflies. The strains of streptococci that cause pyoderma differ from those that cause exudative tonsillitis.

The bacterial toxins cause proteolysis of epidermal and subepidermal layers, allowing the bacteria to spread quickly along the skin layers and thereby cause blisters or purulent lesions. The other common cause of impetigo is Staphylococcus aureus.

Pneumonia

Invasive GAS can cause pulmonary infection, often with rapid progression to necrotizing pneumonia.

Necrotizing fasciitis

Necrotizing fasciitis is caused by bacterial invasion into the subcutaneous tissue, with subsequent spread through superficial and deep fascial planes. The spread of GAS is aided by bacterial toxins and enzymes (eg, lipase, hyaluronidase, collagenase, streptokinase), interactions among organisms (synergistic infections), local tissue factors (eg, decreased blood and oxygen supply), and general host factors (eg, immunocompromised state, chronic illness, surgery).

As the infection spreads deep along the fascial planes, vascular occlusion, tissue ischemia, and necrosis occur. [15] Although GAS is often isolated in cases of necrotizing fasciitis, this disease state is frequently polymicrobial.

Otitis media and sinusitis

These are common suppurative complications of streptococcal tonsillopharyngitis. They are caused by the spread of organisms via the eustachian tube (otitis media) or by direct spread to the sinuses (sinusitis).

Nonsuppurative disease spectrum

Acute rheumatic fever

ARF is a delayed, nonsuppurative sequela of GAS tonsillopharyngitis. Following the pharyngitis, a latent period of 2-3 weeks passes before the signs or symptoms of ARF appear. The disease presents with various clinical manifestations, including arthritis, carditis, chorea, subcutaneous nodules, and erythema marginatum.

Rheumatic fever may be the result of host genetic predisposition. The disease gene may be transmitted either in an autosomal-dominant fashion or in an autosomal-recessive fashion, with limited penetrance. However, the disease gene has not yet been identified.

Considerable evidence supports the link between group A streptococcal infections of the upper respiratory tract and ARF, although only certain M-group serotypes (ie, 1, 3, 5, 6, 18, 24) are associated with this complication. Very mucoid strains, particularly strains of M type 18, have appeared in numerous communities prior to the appearance of rheumatic fever. Rheumatic fever is most frequently observed in children aged 5-15 years (the age group most susceptible to GAS infections).

The attack rate following upper respiratory tract infection is approximately 3% for individuals with untreated or inadequately treated infection. The latent period between the GAS infection and the onset of rheumatic fever varies from 2-4 weeks. In contrast to poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis (PSGN), which may follow either pharyngitis or streptococcal pyoderma, rheumatic fever can occur only after an infection of the upper respiratory tract.

Despite the depth of knowledge that has been accumulated about the molecular microbiology of Streptococcus pyogenes, the pathogenesis of ARF remains unknown. A direct effect of a streptococcal extracellular toxin, in particular streptolysin O, may be responsible for the pathogenesis of ARF, according to some hypotheses. Observations that streptolysin O is cardiotoxic in animal models support this hypothesis, but linking this toxicity to the valvular damage observed in ARF has been difficult.

A more popular hypothesis is that an abnormal host immune response to some component of the group A Streptococcus is responsible. The M protein of GAS shares certain amino acid sequences with some human tissues, and this has been proposed as a source of cross-reactivity between the organism and human host that could lead to an immunopathologic immune response. Also, antigenic similarity between the group-specific polysaccharide of S pyogenes and glycoproteins found in human and bovine cardiac valves has been recognized, and patients with ARF have prolonged persistence of these antibodies compared with controls with uncomplicated pharyngitis. Other GAS antigens appear to cross-react with cardiac sarcolemma membranes. [16]

During the course of the host's immune response to the GAS, the host's antigens may, as a result of this molecular mimicry, be mistaken as foreign; this leads to an inflammatory cascade with resultant tissue damage. In patients with ARF with Sydenham chorea, common antibodies to antigens found in the S pyogenes cell membrane and the caudate nucleus of the brain are present, further supporting the concept of an aberrant autoimmune response in the development of ARF.

Interest in whether such autoimmune responses play a role in the pathogenesis of the syndrome known as pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infections (PANDAS) has been considerable, although further work is necessary to establish the link between streptococcal infections and these syndromes.

Poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis

Glomerulonephritis can follow group A streptococcal infections of either the pharynx or the skin, and incidence varies with the prevalence of so-called nephritogenic strains of group A streptococci in the community. Type 12 is the most frequent M serotype that causes PSGN after pharyngitis, and M type 49 is the serotype most commonly related to pyoderma-associated nephritis. The latent period between GAS infection and the onset of glomerulonephritis varies from 1-2 weeks.

Pathogenesis appears to be immunologically mediated. Immunoglobulins, complement components, and antigens that react with streptococcal antisera are present in the glomerulus early in the course of the disease, and antibodies elicited by nephritogenic streptococci are postulated to react with renal tissue in such a way as to promote glomerular injury. In contrast to acute rheumatic fever, recurrences of PSGN are rare. Diagnosis of PSGN is based on clinical history, physical examination findings, and confirmatory evidence of recent streptococcal infection.

Toxic shock syndrome

Severe GAS infections associated with shock and organ failure have been reported with increasing frequency, predominantly in North America and Europe.

Considerable overlap occurs between streptococcal TSS and streptococcal necrotizing fasciitis, insofar as most cases occur in association with soft-tissue infections. However, streptococcal TSS may also occur in association with other focal streptococcal infections, including pharyngeal infection.

The pathogenesis of streptococcal TSS appears to be related in part to the ability of certain (ie, A, C, F) streptococcal pyogenic exotoxins (SPEs) to function as superantigens.

Scarlet fever

When a fine, diffuse, erythematous rash is present in the setting of acute streptococcal pharyngitis, the illness is called scarlet fever. The rash of scarlet fever is caused by the pyrogenic exotoxins (ie, SPE A, B, C, and F). The rash highly depends on toxin expression; preexisting humoral immunity to the specific SPE toxin prevents the clinical manifestations of scarlet fever.

Scarlet fever has apparently become less common and less virulent than in past decades; however, incidence is cyclic, depending on the prevalence of toxin-producing strains and the immune status of the population. Modes of transmission, age distribution of cases, and other epidemiologic features are similar to those for streptococcal pharyngitis.

Central nervous system diseases

The primary evidence for poststreptococcal autoimmune central nervous system (CNS) disease is provided by studies of Sydenham chorea, the neurologic manifestation of rheumatic fever. Reports of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), tic disorders, and other neuropsychiatric symptoms occurring in association with group A beta-hemolytic streptococcal infections suggest that various CNS sequelae may be triggered by poststreptococcal autoimmunity. [17]

Etiology

S pyogenes is highly communicable and can cause disease in healthy people of all ages who do not have type-specific immunity against the specific serotype responsible for infection. The streptococcus can be present on healthy skin for at least a week before lesions appear.

S pyogenes is primarily spread through person-to-person transmission, although foodborne and waterborne outbreaks have been documented. Neither spread of organisms by fomites nor transmission from animals (eg, family pets) appears to play a significant role in contagion.

Respiratory droplet spread is the major route for transmission of strains associated with upper respiratory tract infection, although skin-to-skin spread is known to occur with strains associated with streptococcal pyoderma. Impetigo serotypes may colonize the throat.

Children with untreated acute infections spread organisms by airborne salivary droplet and nasal discharge. The incubation period for pharyngitis is 2-5 days. Children are usually not infectious within 24 hours after appropriate antibiotic therapy has been started, an observation that has important implications for return to the daycare or school environment.

Individuals who are streptococcal carriers (chronic asymptomatic pharyngeal and nasopharyngeal colonization) are not usually at risk of spreading disease to others because of the generally small reservoir of often-avirulent organisms.

Fingernails and the perianal region can harbor streptococci and can play a role in disseminating impetigo.

Multiple streptococcal infections in the same family are common. Impetigo and pharyngitis are more likely to occur among children living in crowded homes and in suboptimal hygienic conditions.

Epidemiology

As of March 2021, CDC estimates approximately 11,000 to 24,000 cases of invasive group A strep disease occur each year in the United States. Each year between 1,200 and 1,900 people die due to invasive group A strep disease.

Globally, the burden from group A strep infections is even greater. For example, the World Health Organization estimates:

-

111 million children in the developing world have impetigo

-

470,000 new cases of acute rheumatic fever occur each year

-

282,000 new cases of rheumatic heart disease occur each year

-

15.6 million persons have rheumatic heart disease

Group A strep infections can occur any time during the year. However, some infections are more common in the United States in certain seasons:

-

Strep throat and scarlet fever are more common in the winter and spring.

-

Impetigo is more common in the summer.

Anyone can get a group A strep infection, but some infections are more common in certain age groups:

-

Strep throat and scarlet fever are most common in children between the ages of 5 and 15 years.

-

Impetigo is most common in children between the ages of 2 and 5 years.

The most frequent manifestations are pharyngitis, with >616 million incident cases per year, and skin infections, with an estimated 162 million prevalent cases of impetigo. At least 18 million new cases of severe GAS diseases (RHD, ARF, glomerulonephritis, and invasive infections) are estimated to occur annually. Rheumatic heart disease (RHD) alone is responsible for a very large burden of chronic disability and deaths, mostly in adolescents and young adults, particularly pregnant women. The global prevalence of RHD cases was estimated to be 33 million in 2015. Globally, GAS disease and its complications have been reported to cause 500 000 annual deaths, of which 319 000 are due to RHD. [18]

Global mortality due to RHD has somewhat declined since 1990, but no significant decline has been observed in the regions that carry the highest disease burden.

Race- and sex-related demographics

GAS infections are observed worldwide. Streptococcal pyoderma is a more common complication closer to tropical regions of the world. Otherwise, no racial or ethnic predispositions to infection with this organism are recognized.

GAS infections have no sex predilection, although rheumatic mitral stenosis is more common in females.

Age-related demographics

GAS infections may be observed in people of any age, although the prevalence of infection is higher in children, presumably because of the combination of multiple exposures (in school or daycare) and little immunity. Group A streptococcal pharyngitis is particularly common in school-aged children. Strep throat is more common in school-aged children and teens.

Disease in neonates is uncommon, probably in part because of the effect of protective, transplacentally acquired antibody. Prevalence of pharyngeal infection is highest in children older than 3 years. Indeed, group A streptococcal pharyngitis has been described as a hazard in school-aged children. [19] S pyogenes also has the potential to produce outbreaks of disease in younger children in daycare.

Rheumatic fever is most frequently observed in the age group most susceptible to group A streptococcal infections (ie, children aged 5-15 y). The attack rate following upper respiratory tract infection is approximately 3% in individuals with untreated or inadequately treated infection.

ARF is commonly seen in young adults or children aged 4-9 years, while PSGN is more common in persons older than 60 years and in children younger than 15 years.

Prognosis

Acute proliferative PSGN carries a good prognosis, as more than 95% of patients recover spontaneously within 3-4 weeks with no long-term sequelae. With appropriate treatment, pharyngitis and skin infections also have a good prognosis.

As reported by the CDC in April 2008, invasive GAS infections carry an overall mortality rate of 10-15%, with streptococcal TSS and necrotizing fasciitis carrying fatality rates of over 35% and approximately 25%, respectively.

GAS infections and adverse consequences are estimated to cause about 0.5 million annual deaths, in all age ranges, mostly in young adults. [18]

The global prevalence of RHD cases was estimated to be 33 million in 2015. Globally, GAS disease and its complications have been reported to cause 500 000 annual deaths, of which 319 000 are due to RHD. [18]

Complications

Suppurative complications from the spread of streptococci to adjacent structures were very common in the preantibiotic era. Cervical adenitis, peritonsillar abscess, retropharyngeal abscess, otitis media, mastoiditis, and sinusitis still occur in children in whom the primary illness has gone unnoticed or in whom treatment of the pharyngitis has been inadequate because of noncompliance. [20]

Acute hematogenous osteomyelitis is an important complication of streptococcal infection. Isolated bacteremia, meningitis, and endocarditis are described but appear to be rare manifestations of acute infection. [21]

Streptococcal TSS may cause organ system failure (including renal impairment in approximately 80% of patients, and hepatic dysfunction in 65% of patients), while necrotizing fasciitis may result in amputation. [22]

Puerperal sepsis follows abortion or delivery when streptococci that colonize the genital tract invade the endometrium and enter the bloodstream. Pelvic cellulitis, septic pelvic thrombophlebitis, pelvic abscess, and septicemia can occur. Peripartum genital tract infections with group B streptococci are relatively more common, but fatal peripartum GAS infections have been reported. [23]

Empyema develops in 30-40% of pneumonia cases. Other complications of pneumonia include mediastinitis, pericarditis, pneumothorax, and bronchiectasis.

The nonsuppurative complications of GAS tonsillopharyngitis include ARF, rheumatic heart disease, and acute glomerulonephritis.

Patient Education

For patient education resources, see the Infections Center, the Women's Health Center, and the Ear, Nose, and Throat Center, as well as Sore Throat, Toxic Shock Syndrome, and Strep Throat.

-

Invasive soft tissue infection due to Streptococcus pyogenes. This child developed fever and soft-tissue swelling on the fifth day of a varicella-zoster infection. Leading edge aspirate of cellulitis grew S pyogenes. Although the patient responded to intravenous penicillin and clindamycin, operative débridement was necessary because of clinical suspicion of early necrotizing fasciitis.

-

Streptococcus group A infections. Beta hemolysis is demonstrated on blood agar media.

-

Streptococcus group A infections. M protein.

-

Streptococcus group A infections. Erysipelas is a group A streptococcal infection of skin and subcutaneous tissue.

-

Streptococcus group A infections. White strawberry tongue observed in streptococcal pharyngitis. Image courtesy of J. Bashera.

-

Streptococcus group A infections. Streptococcal rash. Image courtesy of J. Bashera.

-

Group A Streptococcus on Gram stain of blood isolated from a patient who developed toxic shock syndrome.

-

Streptococcus group A infections. Necrotizing fasciitis of the left hand in a patient who had severe pain in the affected area.

-

Streptococcus group A infections. Patient who had had necrotizing fasciitis of the left hand and severe pain in the affected area (from Image 8). This photo was taken at a later date, and the wound is healing. The patient required skin grafting.

-

Streptococcus group A infections. Gangrenous streptococcal cellulitis in a patient with diabetes.

-

Erythema secondary to group A streptococcal cellulitis.

-

Invasive soft tissue infection due to Streptococcus pyogenes. This child developed fever and soft-tissue swelling on the fifth day of a varicella-zoster infection. Leading edge aspirate of cellulitis grew S pyogenes. Although the patient responded to intravenous penicillin and clindamycin, operative débridement was necessary because of clinical suspicion of early necrotizing fasciitis.

-

Streptococcus group A infections. Necrotizing fasciitis rapidly progresses from erythema to bullae formation and necrosis of skin and subcutaneous tissue.

-

Throat swab. Video courtesy of Therese Canares, MD; Marleny Franco, MD; and Jonathan Valente, MD (Rhode Island Hospital, Brown University).