Practice Essentials

African trypanosomiasis (sleeping sickness) is an illness endemic to sub-Saharan Africa. It is caused by 2 subspecies of the flagellate protozoan Trypanosoma brucei, which are transmitted to human hosts by bites of infected tsetse flies.

Signs and symptoms

Symptoms of stage 1 (early or hemolymphatic stage) disease may include the following:

-

Painful skin chancre

-

Intermittent fever (refractory to antimalarials and antipyretics)

-

General malaise, myalgia, arthralgias, and headache

-

Generalized or regional lymphadenopathy

-

Facial edema

-

Transient urticarial, erythematous, or macular rashes 6-8 weeks after onset

-

Skin lesions (trypanids)

Symptoms of stage 2 (late or neurologic stage) disease may include the following:

-

Persistent headaches (refractory to analgesics)

-

Daytime somnolence followed by nighttime insomnia

-

Behavioral changes, mood swings, or depression

-

Loss of appetite, wasting syndrome, and weight loss

-

Seizures (more common in children)

Physical findings in stage 1 (early or hemolymphatic stage) disease may include the following:

-

Indurated chancre at bite site

-

Trypanids (skin lesions) in light-skinned patients and irregular rash

-

Lymphadenopathy

-

Fevers, tachycardia, edema, and weight loss

-

Organomegaly, particularly splenomegaly

Physical findings in stage 2 (late or neurologic stage) disease may include the following:

-

CNS manifestations (irritability, tremors, increased muscle rigidity and tonicity, ataxia, hemiparesis)

-

Kerandel sign (delayed pain on compression of soft tissue)

-

Behavioral changes consistent with mania or psychosis, speech disorders, and seizures

-

Stupor and coma

-

Psychosis

-

Sensory disorders

See Presentation for more detail.

Diagnosis

Although general laboratory studies may be helpful, a definitive diagnosis of African trypanosomiasis requires actual detection of trypanosomes.

Significant laboratory abnormalities include the following:

-

Anemia

-

Thrombocytopenia

-

Elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR)

-

Hypergammaglobulinemia

-

Low complement levels

-

Hypoalbuminemia

Studies performed to detect trypanosomes include the following:

-

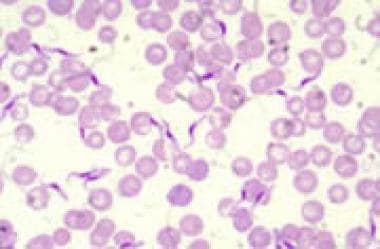

Blood smear (unstained or Giemsa-stained)

-

Chancre aspiration with microscopy

-

Lymph node aspiration with microscopy

-

Bone marrow aspiration with microscopy

-

Lumbar puncture and CSF assay

CSF assay is also done to measure white blood cell (WBC) counts, protein, and IgM in patients with parasitemia or positive serologies or symptoms.

The following studies also may be considered:

-

Computed tomography (CT) of the head

-

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the head

-

Electroencephalography (EEG)

See Workup for more detail.

Management

The type of drug treatment used depends on the type and stage of disease, as follows:

-

East African trypanosomiasis, stage 1 - Suramin

-

East African trypanosomiasis, stage 2 - Melarsoprol

-

West African trypanosomiasis, stage 1 - Pentamidine isethionate, suramin, or fexinidazole

-

West African trypanosomiasis, stage 2 - Nifurtimox and Eflornithine Combination Therapy (NECT), melarsoprol, or fexinidazole

No vaccine is available for African trypanosomiasis. Chemoprophylaxis is unavailable.

In both early- and late-stage trypanosomiasis, symptoms usually resolve after treatment, and the parasitemia clears on repeat blood smears.

Patients who have recovered from late-stage East African trypanosomiasis should undergo lumbar punctures every 3 months for the first year. Patients who have recovered from West African trypanosomiasis may no longer need to undergo lumbar punctures every 6 months for 2 years, depending on their treatment regimen. [1]

See Treatment and Medication for more detail.

Background

African trypanosomiasis, also referred to as sleeping sickness, is an illness endemic to sub-Saharan Africa. It is caused by the flagellate protozoan Trypanosoma brucei, which exists in 2 morphologically identical subspecies transmitted to human hosts by bites of infected tsetse flies, which are found only in Africa, as follows:

-

Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense (East African or Rhodesian African trypanosomiasis) transmitted by infected tsetse flies ( Glossina morsitans).

-

Trypanosoma brucei gambiense (West African or Gambian African trypanosomiasis) transmitted by infected tsetse flies ( Glossina palpalis).

Tsetse flies inhabit rural areas, living in the woodlands and thickets that dot the East African savannah. In central and West Africa, they live in the forests and vegetation along streams. Tsetse flies bite during daylight hours. Unlike other vector-borne diseases, both male and female flies can transmit the infection. Even in areas where African trypanosomiasis is endemic, only a very small percentage of flies are infected. Although the vast majority of infections are transmitted by the tsetse fly, other modes of transmission are possible. Occasionally, a pregnant woman can pass the infection to her unborn baby. In theory, the infection can also be transmitted via blood transfusion or sexual contact, but such cases have rarely been documented.

In West African trypanosomiasis, the reservoirs of infection for these vectors are exclusively human. East African trypanosomiasis, however, is a zoonotic infection with animal vectors. African trypanosomiasis is very distinct from American trypanosomiasis, which is caused by Trypanosoma cruzi and has a different epidemiology, vectors, clinical manifestations, and therapies.

The major epidemiological factor in African trypanosomiasis is contact between humans and tsetse flies. This interaction is influenced by an increasing tsetse fly density, changing feeding habits, and expanding human development into tsetse fly–infested areas.

Pathophysiology and Etiology

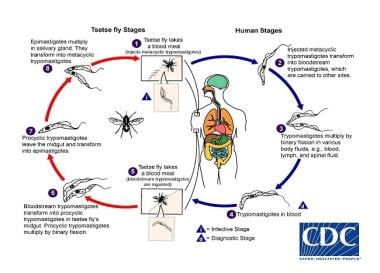

Trypanosomes are parasites with a two-host life cycle: mammalian and arthropod. The life cycle starts when the trypanosomes are ingested during a blood meal by the tsetse fly from either a human reservoir (West African trypanosomiasis) or an animal reservoir (East African trypanosomiasis). The trypanosomes multiply over a period of 2-3 weeks in the fly midgut; then, the trypanosomes migrate to the salivary gland.

Trypanosoma life cycle. Courtesy of the CDC Division of Parasitic Diseases and Malaria (DPDx at https://www.cdc.gov/dpdx/trypanosomiasisafrican/index.html).

Trypanosoma life cycle. Courtesy of the CDC Division of Parasitic Diseases and Malaria (DPDx at https://www.cdc.gov/dpdx/trypanosomiasisafrican/index.html).

Humans are infected with T brucei after a fly bite, which occasionally causes a painful skin chancre at the site 5-15 days later. The injected parasites further mature and divide in the blood and lymphatic system, causing malaise, intermittent fever, rash, and wasting. Eventually, the parasitic invasion reaches the central nervous system (CNS), causing behavioral and neurologic changes (eg, encephalitis and coma). Death may occur.

Innate immunity to trypanosomes results from apolipoprotein L-1 (APOL1), which bind to high-density lipoprotein (HDL) in serum. This protein causes lysis of the trypanosomes when taken up through endocytosis. Disease develops when resistance to APOL1 is acquired.

The parasites escape the host defense mechanisms through extensive antigenic variation of parasite surface glycoproteins (major variant surface glycoprotein [VSG]). This evasion of humoral immune responses contributes to virulence and leads to waves of parasitemia. During the parasitemia, most pathologic changes occur in the hematologic, lymphatic, cardiac, and central nervous systems. This may be the result of immune-mediated reactions against antigens on red blood cells, cardiac tissue, and brain tissue, resulting in hemolysis, anemia, pancarditis, and meningoencephalitis.

A hypersensitivity reaction causes skin problems, including persistent urticaria, pruritus, and facial edema. Increased lymphocyte levels in the spleen and lymph nodes infested with the parasite lead to fibrosis but rarely to splenomegaly. Monocytes, macrophages, and plasma cells infiltrate blood vessels, causing endarteritis and increased vascular permeability.

The gastrointestinal (GI) system is also affected. Kupffer cell hyperplasia occurs in the liver, along with portal infiltration and fatty degeneration. Hepatomegaly is rare. A pancarditis may develop secondary to extensive cellular infiltration and fibrosis (particularly in the East African form). Arrhythmia or cardiac failure can cause death before the development of CNS manifestations (including perivascular infiltration into the interstitium in the brain and spinal cord, leading to meningoencephalitis with edema, bleeding, and granulomatous lesions.

In rare instances, parasitic transmission can result from blood transfusions. Accidental transmission in the laboratory has been implicated in a small number of cases.

Epidemiology

United States statistics

All cases of African trypanosomiasis in the United States are imported from Africa by travelers to endemic areas. Infections among travelers are rare (< 1 case/year among US travelers). Most of these infections are caused by T brucei rhodesiense and are acquired in East African game parks.

International statistics

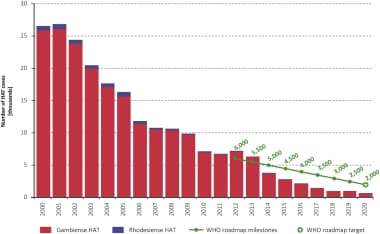

African trypanosomiasis has steadily decreased since 2000. [2]

The cases of Human African Trypanosomiasis (HAT) have decreased annually from 2000 to 2020. Courtesy of PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases [Franco JR, Cecchi G, Paone M, et al. The elimination of human African trypanosomiasis: Achievements in relation to WHO road map targets for 2020. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2022 Jan 18;16(1):e0010047. Online at: https://journals.plos.org/plosntds/article?id=10.1371/journal.pntd.0010047.]

The cases of Human African Trypanosomiasis (HAT) have decreased annually from 2000 to 2020. Courtesy of PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases [Franco JR, Cecchi G, Paone M, et al. The elimination of human African trypanosomiasis: Achievements in relation to WHO road map targets for 2020. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2022 Jan 18;16(1):e0010047. Online at: https://journals.plos.org/plosntds/article?id=10.1371/journal.pntd.0010047.]

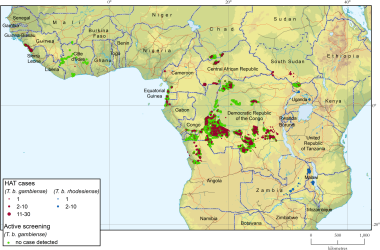

African trypanosomiasis is confined to tropical Africa between latitudes 15°N and 20°S, or from north of South Africa to south of Algeria, Libya, and Egypt. [3] The prevalence of African trypanosomiasis outside this area varies by country and region. In 2005, major outbreaks occurred in Angola, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Sudan. [4] In the Central African Republic, Chad, Congo, Côte d’Ivoire, Guinea, Malawi, Uganda, and Tanzania, African trypanosomiasis remains a major public health problem. [5, 6, 7]

Geographical distribution of human African trypanosomiasis. Courtesy of PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases [Franco JR, Cecchi G, Paone M, et al. The elimination of human African trypanosomiasis: Achievements in relation to WHO road map targets for 2020. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2022 Jan 18;16(1):e0010047. Online at: https://journals.plos.org/plosntds/article?id=10.1371/journal.pntd.0010047.]

Geographical distribution of human African trypanosomiasis. Courtesy of PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases [Franco JR, Cecchi G, Paone M, et al. The elimination of human African trypanosomiasis: Achievements in relation to WHO road map targets for 2020. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2022 Jan 18;16(1):e0010047. Online at: https://journals.plos.org/plosntds/article?id=10.1371/journal.pntd.0010047.]

Fewer than 50 new cases per year are reported in Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, Kenya, Mozambique, Nigeria, Rwanda, Zambia, and Zimbabwe. [8] In Benin, Botswana, Burundi, Ethiopia, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea Bissau, Liberia, Mali, Namibia, Niger, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Swaziland, and Togo, T brucei transmission seems to have stopped, and no new cases of African trypanosomiasis have been reported for several decades.

African trypanosomiasis threatens millions of people in 36 countries of sub-Saharan Africa. The current situation is difficult to assess in numerous endemic countries, because of a lack of surveillance and diagnostic expertise.

In 1986, a panel of experts convened by the World Health Organization (WHO) estimated that 70 million people lived in areas where transmission of African trypanosomiasis is possible. In 1998, almost 40,000 cases of the disease were reported, but in view of the remoteness of the affected regions and the focal nature of the disease, it was clear that this number did not reflect the true situation. It was estimated that 300,000-500,000 more cases were undiagnosed and thus went untreated.

During some epidemic periods, prevalence reached 50% in several villages in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Angola, and South Sudan. African trypanosomiasis was considered the first or second greatest cause of mortality in those communities, even ahead of HIV infection and AIDS. By 2005, surveillance had been reinforced, and the number of new cases reported throughout the continent had been substantially reduced; between 1998 and 2004, the figures for both forms of African trypanosomiasis together fell from 37,991 to 17,616.

In 2009 the World Health Organization (WHO) indicated that the number of new African trypanosomiasis cases dropped below 10 000 for the first time in 50 years, and in 2019 there were with 992 and 663 cases reported in 2019 and 2020 cases recorded respectively. [9]

Age, sex, and race-related demographics

Exposure can occur at any age. Congenital African trypanosomiasis occurs in children, causing psychomotor retardation and seizure disorders. African trypanosomiasis has no sexual or racial predilection.

Prognosis

In early (stage 1) trypanosomiasis, most patients recover fully after treatment. In late (stage 2) trypanosomiasis, the CNS manifestations are ultimately fatal if untreated. The cure rate approaches 95% with drugs that work inside the CNS (eg, melarsoprol).

The symptoms of East African trypanosomiasis develop more quickly (starting 1 month after a bite) than the symptoms of West African trypanosomiasis, which can begin months to a year after the first bite.

Both types of African trypanosomiasis cause the same generalized symptoms, including intermittent fevers, rash, and lymphadenopathy. Notably, individuals with the East African form are more likely to experience cardiac complications and develop CNS disease more quickly, within weeks to a month. The CNS manifestations of behavioral changes, daytime somnolence, nighttime insomnia, stupor, and coma result in death if untreated.

In West African trypanosomiasis, the asymptomatic phase may precede onset of fevers, rash, and cervical lymphadenopathy. If unrecognized, the symptoms then progress to weight loss, asthenia, pruritus, and CNS disease with a more insidious onset. Meningismus is rare. Death at this point is usually due to aspiration or seizures caused by CNS damage.

-

African trypanosomiasis (sleeping sickness). Human trypanosomes blood smear.

-

Trypanosoma life cycle. Courtesy of the CDC Division of Parasitic Diseases and Malaria (DPDx at https://www.cdc.gov/dpdx/trypanosomiasisafrican/index.html).

-

Trypanosoma brucei in a thin blood smear stained with Giemsa. Courtesy of the CDC Division of Parasitic Diseases and Malaria (DPDx at https://www.cdc.gov/dpdx/trypanosomiasisafrican/index.html).

-

Geographical distribution of human African trypanosomiasis. Courtesy of PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases [Franco JR, Cecchi G, Paone M, et al. The elimination of human African trypanosomiasis: Achievements in relation to WHO road map targets for 2020. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2022 Jan 18;16(1):e0010047. Online at: https://journals.plos.org/plosntds/article?id=10.1371/journal.pntd.0010047.]

-

The cases of Human African Trypanosomiasis (HAT) have decreased annually from 2000 to 2020. Courtesy of PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases [Franco JR, Cecchi G, Paone M, et al. The elimination of human African trypanosomiasis: Achievements in relation to WHO road map targets for 2020. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2022 Jan 18;16(1):e0010047. Online at: https://journals.plos.org/plosntds/article?id=10.1371/journal.pntd.0010047.]