Practice Essentials

In Barrett esophagus, healthy esophageal epithelium is replaced with metaplastic columnar cells—the result, it is believed, of damage from prolonged exposure of the esophagus to the refluxate of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). The inherent risk of progression from Barrett esophagus to adenocarcinoma of the esophagus has been established.

Signs and symptoms

The classic picture of a patient with Barrett esophagus is a middle-aged (55 yr) white man with a chronic history of gastroesophageal reflux—for example, pyrosis, acid regurgitation, and, occasionally, dysphagia. Some patients, however, deny having any symptoms.

The features of GERD in relation to long-segment Barrett esophagus (LSBE, >3 cm) and short-segment Barrett esophagus (SSBE, < 3 cm) are quite different.

GERD in LSBE

-

Patients with LSBE tend to have a longer duration of reflux symptoms

-

When undergoing 24-hour esophageal pH monitoring, they have severe, combined patterns of reflux (supine and erect) and reduced lower esophageal sphincter (LES) pressures

-

Patients also tend to be less sensitive to direct acid exposure

GERD in SSBE

Patients are more sensitive to acid exposure but have had symptoms for a shorter duration, with normal LES pressures and only upright reflux on 24-hour esophageal pH testing.

See Presentation for more detail.

Diagnosis

The following techniques are used in the diagnosis and assessment of Barrett esophagus:

-

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD): The procedure of choice for the diagnosis of Barrett esophagus

-

Biopsy: The diagnosis of Barrett esophagus requires biopsy confirmation of specialized intestinal metaplasia (SIM) in the esophagus

-

Ultrasonography: When high-grade dysplasia or cancer is found on surveillance endoscopy, endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) is advisable to evaluate for surgical resectability

The Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology recommends that patients with long-standing GERD symptoms (>5 yr), particularly those aged 50 years or older, have an upper endoscopy to detect or screen for Barrett esophagus.

See Workup for more detail.

Management

Once Barrett esophagus has been identified, patients should undergo periodic surveillance endoscopy to identify histologic markers for increased cancer risk (dysplasia) or cancer that is at an earlier stage and is amenable to therapy. Dysplasia is the best histologic marker for cancer risk.

The management options for high-grade dysplasia include the following:

-

Surveillance endoscopy, with intensive biopsy at 3-month intervals until cancer is detected

-

Endoscopic ablation: In most major medical centers, ablation is first-line therapy

-

Surgical resection: While studies have shown surgery to be efficacious in the control of GERD symptoms, no good evidence indicates that surgical therapy provides regression in Barrett esophagus

Pharmacologic treatment for Barrett esophagus should be the same as that for GERD, although most authorities agree that treatment should employ a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) instead of an H2-receptor antagonist, due to the relative acid insensitivity of patients with Barrett esophagus. While PPIs have been found to be better than H2-receptor antagonists at reducing gastric acid secretion, the evidence as to whether PPIs induce regression of Barrett esophagus remains inconclusive.

Diet

The diet for patients with Barrett esophagus is the same as that recommended for patients with GERD. Patients should avoid the following:

-

Fried or fatty foods

-

Chocolate

-

Peppermint

-

Alcohol

-

Coffee

-

Carbonated beverages

-

Citrus fruits or juices

-

Tomato sauce

-

Ketchup

-

Mustard

-

Vinegar

-

Aspirin and other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

See Treatment and Medication for more detail.

Background

Barrett esophagus (BE) is well recognized as a complication of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). Prolonged exposure of the esophagus to the refluxate of GERD can erode the esophageal mucosa, promote inflammatory cell infiltrate, and ultimately cause epithelial necrosis. This chronic damage is believed to promote the replacement of healthy esophageal epithelium with the metaplastic columnar cells of Barrett esophagus (see the image below). Why only some people with GERD develop Barrett esophagus is not clear.

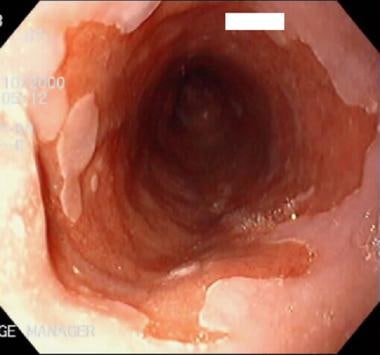

Barrett esophagus (BE). The salmon-pink area has specialized intestinal metaplasia. The white area is squamous epithelium.

Barrett esophagus (BE). The salmon-pink area has specialized intestinal metaplasia. The white area is squamous epithelium.

Histologic characteristics

The definition of Barrett esophagus (BE) has evolved considerably over the past 100 years. In 1906, Tileston, a pathologist, described several patients with "peptic ulcer of the oesophagus" in which the epithelium around the ulcer closely resembled that normally found in the stomach. The debate for the next 4 decades centered on the anatomic origin of this mucosal anomaly. Many investigators, including Barrett in his treatise published in 1950, supported the view that this ulcerated, columnar-lined organ was, in fact, the stomach tethered within the chest by a congenitally short esophagus. [1]

In 1953, Allison and Johnstone argued that the columnar organ was more likely esophagus, because the intrathoracic region lacked a peritoneal covering, contained submucosal glands and muscularis propria characteristic of the esophagus, and could harbor islands of squamous cells within the columnar segment. [2] In 1957, Barrett agreed and suggested that the condition that bears his name be referred to as "lower esophagus lined by columnar epithelium." [3] For the next 2 decades, descriptions of the histology of Barrett esophagus varied considerably from acid-secreting, fundic-type epithelium to intestinal-type epithelium with goblet cells.

Finally, in 1976, Paull et al published a report on the histologic spectrum of Barrett esophagus in which they used manometric guidance for their biopsies. [4] The study's patients had one or a combination of three types of columnar epithelium; ie, a gastric fundic-type, a junctional type, and a distinctive type of intestinal metaplasia the investigators called "specialized columnar epithelium." This specialized intestinal metaplasia (SIM), complete with goblet cells, has become the sine qua non for the diagnosis of Barrett esophagus.

Endoscopic characteristics

Although Paull et al's study clarified the nature of the histologic lesion, the endoscopic definition of Barrett esophagus has continued to evolve. Many people believed that the distal esophagus could contain a normal region of columnar mucosa. In addition, determining the exact location of the esophagogastric junction (EGJ) in patients with Barrett esophagus often is difficult. To avoid false-positive diagnoses, investigators selected arbitrary lengths of columnar-lined esophagus to establish a diagnosis for their studies. Eventually, community endoscopists embraced this practice, and biopsy of the so-called normal distal columnar-lined esophagus was avoided.

Convincing evidence indicates that SIM, the hallmark histologic lesion of Barrett esophagus, predisposes to dysplasia and cancer regardless of the endoscopic location. Thus, the definition of Barrett esophagus currently is the finding of SIM anywhere within the tubular esophagus.

Etiology

As previously stated, Barrett esophagus is well recognized as a complication of GERD. Patients with GERD who develop Barrett esophagus tend to have a combination of clinical features, including hiatal hernia, reduced lower esophageal sphincter (LES) pressures, delayed esophageal acid clearance time, and duodenogastric reflux (as documented by the presence of bile in the esophageal lumen).

Increasing trends for obesity and its associations with GERD and Barrett esophagus are risk factors for esophageal adenocarcinoma. [5] Abdominal obesity independently increases the risk of Barret esophagus. [5, 6]

Pathogenesis of GERD

An understanding of the pathogenesis of GERD is necessary to understand the relationship between GERD and Barrett esophagus. Esophageal defense mechanisms against the noxious substances in the refluxate include an antireflux barrier, an efficient clearing mechanism, and epithelial defense factors.

The antireflux barrier is a high-pressure zone at the EGJ that is generated by tonic contraction of the LES coupled with extrinsic compression by the right crus of the diaphragm. The phrenoesophageal ligament, intra-abdominal location of the LES, and maintenance of an acute angle of entry into the stomach help to reinforce this barrier.

This system is imperfect due to the existence of physiologic transient LES relaxations (TLESRs). TLESRs occur primarily after meals but in the absence of a preceding swallow. Studies indicate that about 95% of reflux episodes in healthy controls occur during the TLESR. Most reflux in patients with GERD occurs via this same mechanism. The duration of esophageal acidification, and not the frequency, correlates best with presence of erosive esophagitis.

A healthy individual clears the esophagus through various means, including gravity, bicarbonate secretion from the salivary and esophageal glands, and peristalsis. Dysfunctional esophageal motility with failed or weak peristalsis is a contributing factor in 34-48% of patients with GERD.

An acid (pH < 4) contact time of 1-2 hours per day is considered normal in the distal esophagus. This physiologic reflux occurs in completely asymptomatic individuals. The esophagus, therefore, must have additional local means of protection.

The esophagus is composed of a thick epithelial layer, with cells joined by tight junctions with lipid-rich intercellular spaces. This arrangement resists the diffusion of noxious substances by limiting entry of H+ into cells and intercellular spaces. In addition, scattered submucosal glands in the distal esophagus that secrete bicarbonate and have an adequate blood supply to deliver bicarbonate and remove H+ help to maintain tissue acid-base balance.

The aggressors in the GERD battle reside in the refluxate. Mucosal injury depends on the pH of the refluxate and the duration of contact with the esophageal mucosa. Lower pH of the refluxate and extended contact with the esophagus increases the time required for intraesophageal pH to return to normal and increases the risk for mucosal injury.

Refluxate exposure and Barrett esophagus

Prolonged exposure of the esophagus to the refluxate can erode the esophageal mucosa, promote inflammatory cell infiltrate, and ultimately cause epithelial necrosis. This chronic damage is believed to promote the replacement of healthy esophageal epithelium with the metaplastic columnar cells of Barrett esophagus, the cellular origin of which remains unknown. This likely is an adaptive response of the esophagus, which, if not for the increased risk of cancer, would have been beneficial. GERD symptoms and strictures are less common in the columnarized segment.

Interestingly, the features of GERD in relation to long-segment Barrett esophagus (LSBE >3 cm) and short-segment Barrett esophagus (SSBE < 3 cm) are quite different. Patients with LSBE tend to have a longer duration of reflux symptoms, and, when undergoing 24-hour esophageal pH monitoring, they have severe, combined patterns of reflux (both supine and erect) and low LES pressures. They also tend to be less sensitive to direct acid exposure. On the other hand, patients with SSBE are more sensitive to acid exposure but have had symptoms for a shorter duration, with normal LES pressures and only upright reflux on 24-hour esophageal pH testing.

Current clinical practice guidelines recommend screening for Barrett esophagus in patients with GERD who have had long-standing symptoms (>5 y); this is especially recommended in white males who are older than 50 years, have central obesity, and symptoms. [7]

Oral bisphosphonate use and Barrett esophagus

Use of oral bisphosphonates was associated with an increased risk of Barrett esophagus, especially among patients with GERD, in a case-control analysis of US veterans, including 285 with definitive Barrett esophagus, 1,122 endoscopy controls, and 496 primary care controls. [8, 9] Overall, 54 (2.8%) of the study participants had filled prescriptions for oral bisphosphonates.

More patients with Barrett esophagus (4.6%) than controls combined (2.5%) had filled prescriptions for any oral bisphosphonate, and significantly more patients with Barrett esophagus (4.2%) than controls (2.2%) had alendronate prescriptions. [8, 9] In a model adjusted for age, sex, race, proton-pump (PPI) inhibitor use, hiatal hernia, H pylori infection, and GERD symptoms, oral bisphosphonates were associated with a significant 2.33-fold increase in the risk of Barrett esophagus. This association increased to 3.29-fold when analyses were limited to patients with GERD symptoms, but there was no association among patients without GERD symptoms. [8, 9] Similarly, the risk was increased 2.71-fold among PPI users, but it was not significantly increased in patients without PPI use.

Epidemiology

The average age of patients with Barrett esophagus is 55-65 years. The condition occurs in a 3:1 male-to-female ratio, with white males making up more than 80% of cases. Some studies indicate a higher prevalence of smoking, alcohol intake, and obesity in persons with the disease. [5, 10]

Estimates of the prevalence of Barrett esophagus vary considerably and range from 0.9-10% of the general adult population.

A study from Sweden by Ronkainen and colleagues estimated the prevalence to be approximately 2% in the adult population. [11] This particular study is believed to be one of the more reliable because of the means by which the epidemiologic data could be assessed in Sweden. In US population terms, this prevalence would equate to approximately 3 million adults with Barrett esophagus.

The prevalence of long-segment Barrett esophagus (LSBE) in patients undergoing endoscopy for any clinical indication has been reported at 0.3-2% but is much higher, 5-15%, in patients with symptoms of GERD. [12] A study conducted at the Mayo Clinic showed an autopsy prevalence about 17 times higher than a clinically matched population, suggesting that most cases of LSBE are asymptomatic and thus unrecognized. In patients undergoing endoscopy, the prevalence of SSBE ranges from 5-30%. The combined prevalence of SSBE and cardia-SIM is 7-8 times greater than LSBE, but the prevalence of dysplasia and cancer is much less.

In a study of 120 young patients (range, 16-19 years; mean age, 16.5 ± 1.4 years) treated for esophageal atresia, Barrett esophagus was associated with esophageal atresia without fistula, previous multiple antireflux surgery, esophageal dilation, suspicion of BE at endoscopy, and histologic esophagitis. [13]

Prognosis

The most significant morbidity associated with Barrett esophagus is the development of adenocarcinoma in the esophagus. [5] However, most patients with Barrett esophagus will not develop esophageal cancer, with the risk of progression to adenocarcinoma of the esophagus being estimated at approximately 0.5% per year in patients without dysplasia on initial surveillance biopsies.

Even so, the incidence of esophageal adenocarcinoma is rising faster than that of any other cancer in the United States. From 1926-1976, 4 large surgical series reported that only 0.8-3.7% of esophageal cancers were adenocarcinomas. [14] From 1979-1992, this increased to 54-68%. The rate of Barrett esophagus increased 50% in adults aged 45 to 64 years between 2012 and 2019, and the rate esophageal cancer nearly doubled. [15]

Blot et al, in a review of data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results program of the National Cancer Institute, determined that the incidence of esophageal adenocarcinoma in 1988-1990 was 3 times that in 1976-1978. [16]

In Olmstead County, Minnesota, Pera et al conducted a population-based study and found that the incidence of esophageal adenocarcinoma rose from 0.13 cases per 100,000 person-years in 1935-1971 to 0.74 cases per 100,000 person-years in 1974-1989. [17] The incidence of adenocarcinoma of the cardia rose from 0.25 to 1.34 cases per 100,000 person-years in the same time period, an increase of more than 5-fold for both locations. Patients with long-segment Barrett esophagus (LSBE) have the greatest risk for development of dysplasia and adenocarcinoma of the esophagus.

Studies report the prevalence of dysplasia in LSBE at 20-35%, in SSBE at 6-8%, and in cardia-SIM at 0-6%, with the prevalence of adenocarcinoma being 7-15 times greater in LSBE than in SSBE and cardia-SIM. However, the total number of patients with SSBE and cardia-SIM is 7-8 times that of LSBE. Thus, even with a higher prevalence of dysplasia and cancer in the LSBE population, a greater total number of patients are likely to develop cancer from within the SSBE and EGJ-SIM group.

-

Barrett esophagus (BE). The salmon-pink area has specialized intestinal metaplasia. The white area is squamous epithelium.

-

Cryoablation of esophageal lining in Barrett esophagus (BE). This is one of the newest experimental ablative therapies for the esophagus performed at the author's laboratory.

-

Blistering of the esophageal mucosal layer after cryoablation in Barrett esophagus (BE).