Background

In the English literature, portal vein obstruction was first reported in 1868 by Balfour and Stewart, who described a patient presenting with an enlarged spleen, ascites, and variceal dilatation. [1]

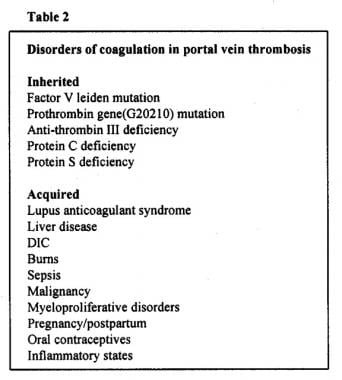

The vast majority of cases are due to primary thrombosis of the portal vein; most of the remaining cases are caused by a malignant obstruction. See the images below.

Portal vein thrombosis with cavernous transformation. The long arrow indicates the splenic vein at the junction with the superior mesenteric vein just below the site of the thrombosis. The short arrow points to a serpiginous mass consistent with periportal collaterals, the so-called cavernous transformation of the portal vein.

Portal vein thrombosis with cavernous transformation. The long arrow indicates the splenic vein at the junction with the superior mesenteric vein just below the site of the thrombosis. The short arrow points to a serpiginous mass consistent with periportal collaterals, the so-called cavernous transformation of the portal vein.

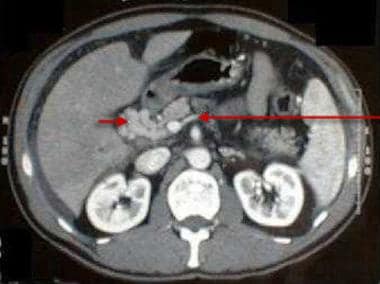

Hepatocellular carcinoma with portal vein thrombosis. The short arrow indicates the tumor thrombus with an abrupt cut off of the portal vein. The long arrow points to a compensatory, prominent left hepatic arterial branch.

Hepatocellular carcinoma with portal vein thrombosis. The short arrow indicates the tumor thrombus with an abrupt cut off of the portal vein. The long arrow points to a compensatory, prominent left hepatic arterial branch.

Pathophysiology

The portal vein forms at the junction of the splenic vein and the superior mesenteric vein behind the pancreatic head, and it can become thrombosed or obstructed at any point along its course. In cirrhosis and hepatic malignancies, the thromboses usually begin intrahepatically and spread to the extrahepatic portal vein. In most other etiologies, the thromboses usually start at the site of the origin of the portal vein. Occasionally, thrombosis of the splenic vein propagates to the portal vein, most often resulting from an adjacent inflammatory process such as chronic pancreatitis.

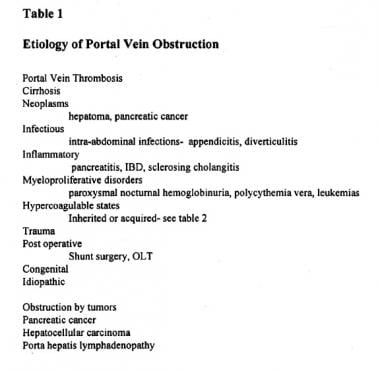

Inherited and acquired disorders of the coagulation pathway are frequent causes of portal vein thrombosis. Inherited disorders include factor V Leiden deficiency and mutations in the prothrombin gene G20210A as well as deficiencies of various intrinsic anticoagulation factors, such as protein C and protein S, and activated protein C resistance. Acquired disorders include antithrombin III deficiency resulting from malnutrition, sepsis, disseminated intravascular coagulation, inflammatory bowel disease, liver disease, or estrogen use. See the image below.

Stasis is another major category for portal vein thrombosis. The global resistance to hepatic blood flow produced by cirrhosis is a common cause. Sclerotherapy for esophageal varices has been postulated as a possible mechanism though not proven thus far. The portal vein or its tributaries can be obstructed by adjacent tumor compression or invasion. Infectious and inflammatory processes may also lead to venous thrombosis.

Portal vein obstruction does not affect the liver function unless the patient has an underlying liver disease such as cirrhosis. [2] This is partially due to a rapid arterial buffer response, with compensatory increased flow of the hepatic artery, maintaining the total hepatic blood flow. Formation of collaterals occurs rather rapidly as well, and they have been described as early as 12 days after an acute thrombosis, though the average time to formation is approximately 5 weeks.

The development of collateral circulation, with its attendant risk of variceal hemorrhage, is responsible for most of the complications and is the most common manifestation of portal vein obstruction. The other sequelae of the subsequent portal hypertension, such as ascites, are less frequent. Rarely, the thrombosis extends from the portal vein to the mesenteric arcades, leading to bowel ischemia and infarction.

Etiology

Children

In children and neonates, the most common etiology is intra-abdominal infection, accounting for 50% of all cases in this age group. Neonatal sepsis with umbilical catheter placement has been reported to be the cause of portal vein thrombosis in 10-26% of cases.

Appendicitis is a commonly reported risk factor in children with portal vein thrombosis.

Congenital anomalies of the portal venous system, often associated with cardiovascular anomalies (eg, ventricular and atrial septal defects, deformed inferior vena cava) and biliary tract abnormalities, have been reported in 20% of children with portal vein obstruction and thrombosis.

Adults

In adults, cirrhosis is the major etiology, accounting for 24-32% of cases of portal vein thrombosis.

Neoplasms are another major cause, accounting for 21-24% of cases of portal vein obstruction, with hepatocellular carcinoma and pancreatic carcinoma causing most of these cases. [3] These tumors can cause compression or direct invasion of the portal vein or lead to thrombosis by inducing a hypercoagulable state. [4] Local ablative therapies for hepatocellular carcinoma or metastatic disease have been linked to its development.

Although less common than in children, infections (predominantly intra-abdominal) still play an important role, with a particular association with Bacteroides fragilis bacteremia.

Myeloproliferative disorders and inherited or acquired hypercoagulable disorders account for 10-12% of cases in adults.

Approximately 8-15% of cases have been reported to be idiopathic in the recent literature. For other less common etiologies, such as abdominal trauma, surgery, and inflammatory bowel disease, see the image below.

Epidemiology

United States statistics

Portal vein obstruction is a relatively rare condition with an overall incidence of 0.05-0.5% in autopsy studies. [5] The incidence varies, depending on the group of patients studied (eg, general population vs patients with cirrhosis) and the method used to diagnose portal vein obstruction (eg, autopsy studies, angiography studies, noninvasive radiological screening).

The incidence of portal vein obstruction in people with cirrhosis has been reported to vary from 5-18%. However, these were patients referred for transplantation and were at an advanced stage of liver disease. No large autopsy studies are available. Extrahepatic portal vein obstruction is estimated to be responsible for 5-10% of all cases of portal hypertension.

International statistics

In Japan, the frequency of portal vein obstruction in autopsy studies was reported to be 0.05%. [5] In an angiography surveillance study of patients with cirrhosis, the incidence was 0.5%, which is much lower than the reported incidence in the Western literature.

In India, extrahepatic portal vein obstruction is reported more frequently; in one study, the incidence even exceeded reported cases of cirrhosis. Of all cases of portal hypertension in developing countries, 40% are attributed to portal vein obstruction, presumably secondary to an increased incidence of pylephlebitis associated with abdominal infections.

Sex- and age-related demographics

No sex differences have been reported overall, except for a slight male predominance in patients whose obstruction is secondary to cirrhosis.

The distribution of the age at presentation of portal vein thrombosis reflects the demographics of the underlying disease process. Primary portal vein thrombosis from coagulopathies occurs with equal frequency in adults and children. [6] The frequency of portal vein obstruction from tumor compression or invasion is greater in adults.

Prognosis

The overall prognosis is good, with 75% of patients alive after 10 years and an overall mortality rate of less than 10%. [7]

In the presence of cirrhosis and malignancy, the prognosis is understandably worse and is dependent upon the underlying condition.

Mortality/Morbidity

In the absence of cirrhosis, the 2 year bleeding risk from esophageal varices is reported to be 0.25% and of those that bleed the mortality rate is approximately 5%. Those with cirrhosis and varices have a 20-30% 2 year bleeding risk with a mortality rate of 30-70%. This difference is primarily a consequence of the normal hepatic function in the noncirrhotic patient. The variceal size is the major predictive factor for bleeding.

In adults with portal vein thrombosis, the 10-year survival rate has been reported to be 38-60%, with most of the deaths occurring secondary to the underlying disease (eg, cirrhosis, malignancy).

In children with portal vein thrombosis, the prognosis is much better overall, with a 10-year survival rate greater than 70%, which is attributable to the low incidence of an underlying malignancy and cirrhosis.

Complications

Complications of portal vein obstruction include the following:

-

Variceal hemorrhage

-

Ascites

-

Mesenteric infarction

-

Hypersplenism

-

Hepatic encephalopathy (rare)

-

Worsening hepatic function in patients with cirrhosis

-

Death

-

The etiology of portal vein obstruction.

-

Coagulation disorders in portal vein thrombosis.

-

Portal vein thrombosis with cavernous transformation. The long arrow indicates the splenic vein at the junction with the superior mesenteric vein just below the site of the thrombosis. The short arrow points to a serpiginous mass consistent with periportal collaterals, the so-called cavernous transformation of the portal vein.

-

Hepatocellular carcinoma with portal vein thrombosis. The short arrow indicates the tumor thrombus with an abrupt cut off of the portal vein. The long arrow points to a compensatory, prominent left hepatic arterial branch.