Background

The word ascites is of Greek origin (askos) and means bag or sac. Ascites describes the condition of pathologic fluid collection within the abdominal cavity (see the image below). Healthy men have little or no intraperitoneal fluid, but women may normally have as much as 20 mL, depending on the phase of their menstrual cycle. [1] This article focuses only on ascites associated with cirrhosis.

Pathophysiology

The accumulation of ascitic fluid represents a state of total-body sodium and water excess, but the event that initiates the unbalance is unclear. Although many pathogenic processes have been implicated in the development of abdominal ascites, about 75% likely occur as a result of portal hypertension in the setting of liver cirrhosis, with the remainder due to infective, inflammatory, and infiltrative conditions. [2]

Three theories of ascites formation have been proposed: underfilling, overflow, and peripheral arterial vasodilation.

The underfilling theory suggests that the primary abnormality is inappropriate sequestration of fluid within the splanchnic vascular bed due to portal hypertension and a consequent decrease in effective circulating blood volume. This activates the plasma renin, aldosterone, and sympathetic nervous system, resulting in renal sodium and water retention.

The overflow theory suggests that the primary abnormality is inappropriate renal retention of sodium and water in the absence of volume depletion. This theory was developed in accordance with the observation that patients with cirrhosis have intravascular hypervolemia rather than hypovolemia.

The peripheral arterial vasodilation hypothesis includes components of both of the other theories. It suggests that portal hypertension leads to vasodilation, which causes decreased effective arterial blood volume. As the natural history of the disease progresses, neurohumoral excitation increases, more renal sodium is retained, and plasma volume expands. This leads to overflow of fluid into the peritoneal cavity. The vasodilation theory proposes that underfilling is operative early and overflow is operative late in the natural history of cirrhosis.

Although the sequence of events that occurs between the development of portal hypertension and renal sodium retention is not entirely clear, portal hypertension apparently leads to an increase in nitric oxide levels. Nitric oxide mediates splanchnic and peripheral vasodilation. Hepatic artery nitric oxide synthase activity is greater in patients with ascites than in those without ascites.

Regardless of the initiating event, a number of factors contribute to the accumulation of fluid in the abdominal cavity. Elevated levels of epinephrine and norepinephrine are well-documented factors. Hypoalbuminemia and reduced plasma oncotic pressure favor the extravasation of fluid from the plasma to the peritoneal fluid, and, thus, ascites is infrequent in patients with cirrhosis unless both portal hypertension and hypoalbuminemia are present.

Etiology

Normal peritoneum

Portal hypertension (serum-ascites albumin gradient [SAAG] >1.1 g/dL)

-

Hepatic congestion, congestive heart failure, constrictive pericarditis, tricuspid insufficiency, Budd-Chiari syndrome

-

Liver disease, cirrhosis, alcoholic hepatitis, fulminant hepatic failure, massive hepatic metastases

Hypoalbuminemia (SAAG < 1.1 g/dL)

-

Nephrotic syndrome

-

Protein-losing enteropathy

-

Severe malnutrition with anasarca

Miscellaneous conditions (SAAG < 1.1 g/dL)

-

Chylous ascites (11%) [3] : The extent of abdominal surgery is the main predictor for the risk of chylous ascites

-

Pancreatic ascites

-

Bile ascites

-

Nephrogenic ascites

-

Urine ascites

-

Ovarian disease

Diseased peritoneum (SAAG < 1.1 g/dL)

Infections

-

Bacterial peritonitis

-

Tuberculous peritonitis

-

Fungal peritonitis

-

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-associated peritonitis

Malignant conditions

-

Peritoneal carcinomatosis

-

Primary mesothelioma

-

Pseudomyxoma peritonei

-

Hepatocellular carcinoma

Other rare conditions

-

Vasculitis

-

Granulomatous peritonitis

-

Eosinophilic peritonitis

Epidemiology

The prevalence of chronic liver disease and cirrhosis in the United States is estimated to be 4.5 million. [4] The incidence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) is expected to rise, leading to an increased incidence of cirrhosis. [5]

Prognosis

The prognosis for patients with ascites due to liver disease depends on the underlying disorder, the degree of reversibility of a given disease process, and the response to treatment.

Morbidity/mortality

Worldwide, cirrhosis accounts for an estimated 1 million deaths per year. [6] Ambulatory patients with an episode of cirrhotic ascites have a 3-year mortality rate of 50%. The development of refractory ascites carries a poor prognosis, with a 1-year survival rate of less than 50%. [7]

Complications

The most common complication of ascites is the development of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (ascitic fluid with PMN count of >250 μ L). Note the following:

-

Performing repeated physical examinations and paying particular attention to abdominal tenderness may be the best way to become aware of the possible development of this complication. In a study of 133 hospitalized patients with ascites, abdominal pain and abdominal tenderness were more common in patients with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (P< 0.01), but no other physical sign or laboratory test could separate spontaneous bacterial peritonitis cases from other cases. [8]

-

Any patient with ascites and fever should have a paracentesis with bedside blood culture inoculation and cell count. Patients with a protein level of less than 1 g/dL in ascitic fluid are at high risk for the development of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Prophylactic antibiotic therapy with a quinolone is often recommended.

Complications of paracentesis include infection, electrolyte imbalances, bleeding, and bowel perforation. Bowel perforation should be considered in any patient with recent paracentesis who develops a new onset of fever and/or abdominal pain. All patients with long-standing ascites are at risk of developing umbilical hernias. Large-volume paracentesis often results in large intravascular fluid shifts. This can be avoided by administering albumin replacement if more than 5 L is removed.

Acute kidney injury in the setting of ascites and cirrhosis is a medical emergency, requiring prompt diagnosis and multimodal management. [9]

Patient Education

The most important aspect of patient education is determining when therapy is failing and recognizing the need to see a physician. Unfortunately, in most cases, liver failure has a dismal prognosis. All patients must be taught which complications are potentially fatal and the signs and symptoms that precede them.

Abdominal distention and/or pain despite maximal diuretic therapy are common problems, and patients must realize the importance of seeing a physician immediately.

-

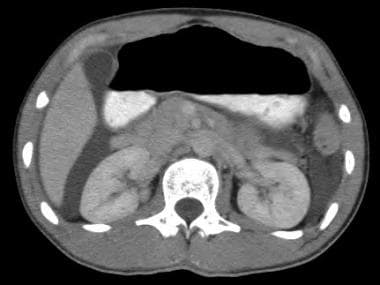

Ascites. This computed tomography scan demonstrates free intraperitoneal fluid due to urinary ascites.

-

Ascites. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS).

-

Ascites. Massive ascites.