Practice Essentials

Angioedema is the swelling of deep dermis, subcutaneous, or submucosal tissue due to vascular leakage. [1, 2] Acute episodes often involve the lip, eyes, and face (see the image below); however, angioedema may affect other parts of body, including respiratory and gastrointestinal (GI) mucosa. Laryngeal swelling can be life-threatening.

Signs and symptoms

Angioedema may affect many organ systems. Visible swelling is common in peripheral angioedema. It is often associated with local burning sensation and pain without pronounced itchiness or local erythema. The most commonly involved areas are:

-

Peripheral swelling: skin and urogenital area (e.g., eyelids or lips, tongue, hands, feet, scrotum, etc.)

-

Abdomen: Abdominal pain (sometimes it can be the only presenting symptom of angioedema)

-

Larynx: Throat tightness, voice changes, and breathing trouble (indicators of possible airway involvement), potentially life-threatening.

See Presentation for more detail.

Diagnosis

Examination in patients with suspected angioedema includes the following:

-

Dermatologic – Areas of swelling with or without erythematous skin, often with ill-defined margins; the face, extremities, and genitalia are most commonly affected [3]

-

GI – No specific findings may be present, even in severe cases of angioedema, or there may be abdominal distention and signs consistent with bowel obstruction; changes in bowel sounds and diffuse or localized tenderness may be present; the clinical picture may resemble that of an acute abdomen

-

Upper airway – Direct visualization of the uvula or tongue swelling; laryngoscopy is needed to assess laryngeal or vocal cord involvement; document swelling by means of physician notes, photographs, or both

Severe attacks of angioedema can herald the onset of systemic anaphylaxis, characterized initially by dyspnea. Many cases of angioedema occur in patients with urticaria.

Testing

Most mild cases of angioedema do not require laboratory testing. Suspected allergies to food, stinging insects, latex, and antibiotics can be screened and diagnosed. The value of aeroallergen screening for patients with angioedema is limited, except with regard to establishing atopic status.

For angioedema without urticaria (especially those with recurrent episodes), diagnostic tests should include the following:

-

C4 level

-

C1 esterase inhibitor (C1-INH) quantitative and functional measurements

-

C1q level

Screening laboratory studies have limited value in most cases. For chronic or recurrent angioedema without a clear trigger, clinicians may consider the following tests:

-

CBC with differential

-

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP) level

-

D-dimer level

-

Urinalysis

-

Comprehensive metabolic profile

-

Antinuclear antibody (ANA) testing

-

CH50 level

-

Thyroid studies, including levels of thyroid stimulating hormone, free T4, and thyroid autoantibodies (antimicrosomal and antithyroglobulin), particularly in women or in patients with a family history of thyroid disease or other autoimmune diseases

If the history and physical examination findings suggest specific problems, other tests that may be helpful include the following:

-

Stool analysis for ova and parasites

-

Helicobacter pylori workup

-

Hepatitis B and C virus workup

-

Rheumatoid factor

-

Cryoglobulin levels

-

Imaging studies

Imaging studies

Most angioedema patients do not need any imaging studies. However, when internal organ involvement is suspected, during acute attacks, the following studies can be performed:

-

Plain abdominal films – These may show a “stacked coin” or “thumbprint” appearance of the intestines [4]

-

Abdominal ultrasonography – This may show ascites.

-

Abdominal computed tomography – This may show severe edema of the bowel wall [1]

-

Chest radiography – This may show pleural effusion

-

Soft-tissue neck radiography – This may show soft-tissue swelling [5]

See Workup for more detail.

Management

The primary goal of medical treatment for angioedema is to reduce and prevent swelling, as well as to reduce discomfort and complication.

Most medications used in treating urticaria and anaphylaxis are also used in the management of many types of angioedema. Epinephrine should be used when laryngeal angioedema is suspected. In addition, supportive care should be provided, regardless of the etiology.

Pharmacotherapy

Medications used in the management of angioedema include the following:

-

Alpha- and beta-adrenergic agonist agents (eg, epinephrine)

-

First-generation antihistamines (eg, diphenhydramine, chlorpheniramine, cyproheptadine, hydroxyzine hydrochloride)

-

Second-generation antihistamines (eg, cetirizine, desloratadine, fexofenadine, levocetirizine, loratadine)

-

Histamine H2 antagonists (eg, ranitidine, cimetidine)

-

Leukotriene receptor antagonists (eg, montelukast, zafirlukast)

-

Tricyclic antidepressants (eg, doxepin)

-

Corticosteroids (eg, prednisone, methylprednisolone, prednisolone)

-

Androgen derivatives (eg, danazol, oxandrolone), progesterone-based birth control pills.

-

Antifibrinolytic agents (eg, aminocaproic acid, tranexamic acid)

-

Immunomodulators (eg, cyclosporine, mycophenolate, methotrexate, )

-

Agents for treatment or prophylaxis: C1 INH concentrates, ecallantide, lanadelumab, and icatibant.

Surgical option

In severe cases of laryngeal edema, a surgical airway must be created via cricothyrotomy or tracheotomy.

See Treatment and Medication for more detail.

Background

Angioedema, first described in 1586, [6] is usually defined by pronounced swelling of the deep dermis, subcutaneous or submucosal tissue, or mucous membranes as a result of vascular leakage. [3] Other terms, such as giant urticaria, [7] Quincke edema, [8] and angioneurotic edema, [9] have also been used in the past to describe this condition. Clinically, angioedema is usually nonpitting and nonpruritic. Involved skin often shows no change in color or may be slightly erythematous (see the image below).

Angioedema is most commonly observed affecting the lips and eyes (periorbital). Other commonly involved areas may include the face, hands, feet, and genitalia. However, this condition is not always visible, as in cases involving the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. [10] Depending on the area of swelling, pain can be absent or mild, as in most peripheral or facial swelling, or it can be very severe, as in GI angioedema. (See Presentation.)

Swelling that involves the tongue and upper airways is cause for greater concern than swelling involving other areas, owing to the potential of airway compromise. [11, 12] Laryngeal swelling is life-threatening and should be treated as a medical emergency.

Disfiguration, pain, and reduced function are common complaints in patients with angioedema, but this condition is also commonly associated with urticaria. When both angioedema and urticaria are evident during clinical presentation, the episode is primarily mast cell−mediated. [13] Affected patients describe subjective pruritus, sometimes associated with hypersensitivity to an offending agent (eg, a food or drug). However, the underlying triggers are often unidentifiable.

There are also a significant number of angioedema cases that present with angioedema alone. In such cases, the clinical presentation, trigger, cause, and response to treatment may be quite different from those in cases that present with both angioedema and urticaria; therefore, some experts believe that these patients may (at least in part) have different pathophysiologic mechanisms. [11] Many such cases do not respond to antihistamines. Vasoactive mediators other than histamine (eg, bradykinin) may be involved in the swelling. [11] (See Pathophysiology.)

Although angioedema can manifest as an episodic or self-limiting event, it can often be described as recurrent or chronic. Thus, classification is not always straightforward. Because most cases of angioedema are found to be associated with urticaria, those cases usually follow the classification of urticaria (ie, acute vs chronic or induced vs spontaneous). [14] For angioedema that is not associated with urticaria, other classifications have been suggested. [15, 11] (See Classification and Subtypes of Angioedema.) The most recent classification for recurrent angioedema without the presence of urticaria has also been proposed by an international angioedema work group. [16]

This article concentrates on angioedema without urticaria. For angioedema associated with urticaria, the treatment strategies are essentially the same as those for acute urticaria (see Acute Urticaria). Angioedema caused by decreased functional C1-esterase inhibitor (C1-INH) is covered elsewhere as well (see Hereditary Angioedema [HAE] and Acquired Angioedema [AAE]).

Pathophysiology

Angioedema is a result of the fast onset of an increase in local vascular permeability in subcutaneous or submucosal tissue. Histamine and bradykinin are the most recognized vasoactive mediators known to be critical in the pathologic process of angioedema; most cases of angioedema are primarily mediated by 1 of these 2 mediators, though some investigators indicate the possibility that both may be involved in certain cases. [17] (See Classification and Subtypes of Angioedema.)

Other vasoactive mediators are, at least in part, involved in the pathogenesis of various types of angioedema. Leukotrienes, for example, may play an important role in the onset of angioedema that is induced by nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). [18] Thus, factors influencing histamine release, bradykinin metabolism, and endothelial cell function or permeability may directly or indirectly regulate the process of angioedema.

Histamine- and bradykinin-mediated angioedema

For histamine-mediated angioedema (histaminergic angioedema), mast cells and basophils are the primary sources of histamine. The activation of mast cells or basophils with subsequent histamine release may be either mediated or unmediated by immunoglobulin E (IgE). IgE-mediated mast cell activation and degranulation, key elements of an allergic reaction, often manifest as urticaria and angioedema. Type I hypersensitivity reactions, such as food or drug allergies, are typically IgE-mediated.

Non–IgE-mediated mast cell activation or mediator release may explain certain autoimmune-mediated and idiopathic angioedema. [19] Numerous inflammatory mediators and cytokines and chemokines are known to influence histamine release and activation of mast cells and basophils. In addition, C3a and C5a are known to activate mast cells or basophils via an IgE-independent pathway.

Mast cells can also be activated by other non–IgE-mediated processes, such as the binding of IgG antibodies to IgE receptors on mast cells or basophils, leading to spontaneous mast cell activation and histamine release. Another example of non–IgE-mediated mast-cell activation is the reaction induced by intravenous (IV) contrast material.

Plasma and tissue factors, such as bradykinin, and certain components in the contact system or the fibrinolytic system are also found to play an important role in certain forms of angioedema. [20, 21] For angioedema without evidence of histamine involvement, bradykinin is likely the most important mediator. [11]

Hereditary angioedema (HAE), angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor–induced angioedema, and certain idiopathic angioedemas are examples of bradykinin-mediated angioedema; bradykinin levels are elevated during an episode of angioedema. [13] Accumulation of bradykinin, either from overproduction or from decreased breakdown, accounts for the pathogenesis of these types of angioedema. [20]

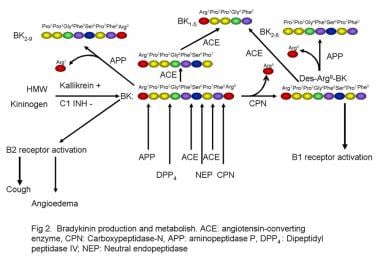

C1-INH is a serine protease that is involved in the regulation of bradykinin, a potent vasoactive substance. Low levels of this protease (either hereditary or acquired) results in unchecked activation of the kallikrein-kinin system, which leads to the overproduction of bradykinin (see the image below). [22] (See Hereditary Angioedema.)

Other mediators

Besides mast cells, many other cellular components (eg, macrophages, dendritic cells, lymphocytes, monocytes, eosinophils, and endothelial cells) are involved in the pathogenesis of angioedema. [3, 23] These contribute to the generation, maturation, and activation of mast cells and basophils and thereby exert an influence on histamine release. [24] Release of vasoactive substances causes vasodilatation of endothelial cells, as well as smooth muscle bowel contraction, [25] ultimately manifesting in the common clinical presentation of the disease.

Urticaria and angioedema

Urticaria is often discussed together with angioedema. In many cases, the 2 conditions are remarkably similar, both in their underlying etiologies and in the clinical management strategies employed to treat them. However, angioedema is also quite different from urticaria, in that it usually involves a deeper layer of skin (reticular dermis) or subcutaneous or submucosal tissue, whereas urticaria affects a more superficial layer of skin (papillary dermis and mid-dermis). In fact, mucosal involvement is observed only in angioedema but not in urticaria.

In addition, pruritus is the most prominent complaint in urticaria, but it is less troublesome or absent in angioedema. Furthermore, pain or tenderness is uncommon in urticaria but frequent or even severe in angioedema. Addressing these differences is necessary for successful treatment of angioedema.

Angioedema with and without urticaria

Angioedema associated with urticaria may represent hypersensitivity to an offending agent. Histamine is released into the bloodstream, resulting in increased endothelial cell permeability. Angioedema, generalized urticaria, and, in severe cases, anaphylaxis will occur. [26] The allergen binds to the mast cell, causing degranulation and histamine and tryptase release. Degranulations of mast cells have also been shown to be a direct result of anesthetics, contrast media, and opiates. [26]

Autoantibodies against the mast cell IgE receptor or mast cell−bound IgE (or basophils) are another common cause of histamine release. Additionally, proteases may activate the complement cascade associated with C3a, C4a, and C5a, which are considered anaphylactoids, and result in increased capillary permeability and extravasation of fluid. [25]

With respect to pathophysiology, angioedema without urticaria may differ substantially from angioedema with urticaria. In many cases, histamine is not involved or only minimally involved. Bradykinin is known to be the major mediator for HAE, acquired angioedema (AAE), ACE inhibitor–induced angioedema, and certain idiopathic angioedemas.

HAE and AAE

The following 3 types of HAE have been identified:

-

Type I – C1-INH deficiency

There are no reliable diagnostic tests to establish the diagnosis of type III HAE; rather the patient’s family history and clinical presentation are key diagnostic components. Originally described as affecting women only, type III HAE was subsequently reported in a few men as well. [34] Orofacial involvement seems to be the most common presentation for type III HAE, but abdominal attacks are seen less frequently in this variant. The new classification has proposed to combine HAE Type I and II and name it as C1-IHN HAE, whereas HAE Type III is to be differentiated into FXII-HAE and U-HAE. [16]

AAE (now preferred to be named as C1-INH-AAE) is classified as either type I or type II. [13]

C1-INH-AAE Type I is associated with B-cell proliferative disorders and is characterized by hypercatabolization of C1-INH. Immune complexes are formed between antibodies and abnormal immunoglobulins on the cell surface of B cells. The complement cascade hyperreacts, producing large amounts of C1. C1-INH is then consumed in attempts to prevent the activation of the continuously activated C1. As a result, levels of serum C1q are decreased in patients with C1-INH-AAE, but not in those with C1-INH-HAE (see Laboratory Studies).

The relative deficiency of C1-INH causes increased activation of the kallikrein-kinin system. [35, 25] Enzymatic cleavage by kallikrein is increased with consumption of kininogen, and subsequently, the production of bradykinin increases. The end result of this intricate molecular cascade is vasodilation meditated by the interaction of kinins with the endothelial cell receptors B1R and B2R. [36]

Type II AAE is associated with autoantibodies (IgG, and less often, IgM) directed against the C1-INH molecule. [25] Depletion of C1-INH results in the production of large amounts of bradykinin and other vasoactive substances, which causes the signs and symptoms of angioedema.

Etiology

More than 40% of chronic angioedema is idiopathic. Trauma, surgical procedures, and stress are common nonspecific triggers for angioedema attacks.

Angioedemas with identifiable etiologies include those caused by the following:

-

Hypersensitivity (eg, food, drugs, or insect stings)

-

Physical stimuli (eg, cold or vibrations)

-

Autoimmune disease or infection

-

ACE inhibitors

-

NSAIDs

-

C1-INH deficiency (hereditary and acquired)

Angioedemas with unidentifiable etiologies include idiopathic angioedema (histaminergic or nonhistaminergic).

Angioedema has also been associated with certain conditions or syndromes, such as the following:

-

Cytokine-associated angioedema syndrome (ie, Gleich syndrome or episodic angioedema with eosinophilia) [37]

-

Well syndrome or eosinophilic cellulitis (ie, granulomatous dermatitis with eosinophilia) [38]

Hypersensitivity angioedema

Hypersensitivity (allergic) angioedema is often associated with urticaria. It is typically observed within 30 minutes to 2 hours after exposure to the allergen. Mast cell–mediated angioedema or urticaria may be triggered by food, drugs, animal bites, stings (eg, from Hymenoptera), preservatives, or food coloring. [13] Food coloring and preservatives may cause angioedema with or without urticaria. [25]

Allergic angioedema may be associated with urticaria and anaphylaxis. In an Australian study of all anaphylaxis presentations to an adult emergency department (ED) in a single year, angioedema was present in 40% of the 142 cases (49.3% of those with urticaria). [39] In a Korean study, 69.4% of 138 patients who had anaphylaxis were found to have angioedema. [40]

Pseudoallergic angioedema

“Pseudoallergic” angioedema (PAE) is not mediated by IgE; that is, the angioedema is caused by a nonallergic or nonimmunologic reaction. However, its clinical course and presentation are very similar to those of allergic angioedema. Typical examples are angioedema induced by NSAIDs and that induced by intravenous (IV) contrast material; aspirin (ASA) is the most common culprit.

True IgE-mediated reactions to ASA or other NSAIDs are uncommon. The angioedema (with or without urticaria) reflects the pharmacologic properties of the drugs. By inhibiting cyclooxygenase (COX), ASA and NSAIDs cause overproduction of proinflammatory and vasoactive leukotrienes. COX-2 inhibitors and acetaminophen (APAP) do not usually cause angioedema.

Nonallergic angioedema

Nonallergic angioedema does not involve IgE or histamine and is generally not associated with urticaria. The 5 types of nonallergic angioedema are as follows [20] :

-

HAE

-

AAE

-

Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS)-blocker-induced angioedema (RAE)

-

PAE

-

IAE

Hereditary angioedema

HAE, a rare autosomal dominant disorder, is perhaps the prototype of nonallergic angioedema. [27] Most patients report a family history of disease, but approximately 20–25% of cases are the result of spontaneous mutations. More than 150 mutations in the C1 INH gene on the long arm of chromosome 11 have been associated with HAE. [41] As noted (see Pathophysiology), 3 types of HAE have been identified.

Acquired angioedema

Acquired angioedema, now known as C1-INH-AAE is a rare disorder caused by accelerated consumption of C1-INH or the production of autoantibodies to C1-INH. Onset is usually in the fourth decade of life. C1-INH-AAE is often associated with autoimmune diseases and lymphoproliferative disorders. [25]

ACE inhibitor–induced angioedema (ACEI-AAE or AIIA)

ACE inhibitors can precipitate attacks of angioedema by directly interfering with the degradation of bradykinin, thereby potentiating its vasoactive effect. ACE inhibitor–induced angioedema (AIIA or ACEI-AAE) is bradykinin-mediated, as in cases of HAE and AAE. ACEI-AAE occurs when ACE inhibitors interfere with the degradation of bradykinin, a potent vasoactive nonapeptide.

In a multicenter study, ACEI-AAE accounted for almost one-third of angioedema cases treated in the ED; however, it remains a rare ED presentation. [42] Most ACEI-AAE is observed in the first week after starting the medicine; in as many as 30% of cases, however, onset occurs after months, or even years, of taking the medicine. [30, 42] In later-onset cases, the ACE inhibitor can easily be overlooked as a cause of angioedema.

The most common sites of ACEI-AAE are the face, lip, and tongue, but abdominal involvement has been reported as well. [3] Abdominal computed tomography (CT) can be informative in cases with GI involvement. [2]

Genetic screening for ACE polymorphism may help identify the population at risk for ACEI-AAE. In 0-9.2% of cases, patients with ACEI-AAE may develop angioedema when switching to an angiotensin II receptor blocker (ARB). [30]

Physically induced angioedema

Physically induced angioedema is caused by physical agents, such as cold, heat pressure, vibration, and ultraviolet radiation. [25] This manifestation may occur with or without urticaria. Cold-induced angioedema and urticaria have been reported in association with cryoglobulins, cold agglutinin disease, cryofibrinogenemia, and paroxysmal cold hemoglobinuria. (See Anaphylaxis, Urticaria, and Acute Urticaria.)

Idiopathic angioedema

The causes of IAE are, by definition, not identifiable. Furthermore, the exact mechanisms are unclear, though nonspecific mast cell activation and degranulation are suspected. [43, 26] On the basis of responses to medication, some cases are thought to be mediated by mast cell activation, albeit independent of IgE. Some cases may be associated with urticaria. Common triggers include heat, cold, emotional stress, and exercise.

Other causes

The link between infection and angioedema is vague at best. Helicobacter pylori infection has been found to be associated with HAE exacerbation, and treatment of H pylori infection has led to clinical improvement of chronic urticaria and angioedema. [28] Systemic viral, bacterial, or parasitic infection may stimulate the immune system and cause improper activation or inflammatory changes.

C1-INH functions normally in estrogen-dependent angioedema. [44] This has been proposed as HAE type III. The exact mechanism of angioedema in these patients is still unclear. [31] In some of the affected patients, factor XII (FXII) point mutation results in a gain of function that can potentially affect the metabolism of bradykinin. [45]

Patients with Gleich syndrome exhibit elevated eosinophil levels with angioedema. Gleich syndrome, which responds well to corticosteroids, is thought to be related to hypereosinophilic syndrome. [46] In addition to the elevated eosinophil count, immunoglobulin G (IgG) autoantibody against endothelial cells has been identified.

Thyroid autoantibodies are found in 14-28% of patients with chronic urticaria or angioedema, and IgG autoantibodies to either the high-affinity receptor for IgE (FceRI) or to IgE are found in 30-50% of these patients. [43, 28] In affected individuals, autoantibody (IgG) has been found to crosslink FceRI on mast cells, resulting in mast cell activation and release of histamine, cytokines, and other proinflammatory mediators. Immunomodulatory drugs may be beneficial for this type of angioedema. [47]

Epidemiology

United States statistics

The reported incidence or prevalence of angioedema varies depends on the study population and the method of study (eg, patient reported vs physician diagnosed). The World Allergy Organization (WAO) notes that urticaria and angioedema affects up to 20% of the population. [14] It is estimated that approximately 10-20% of population may experience at least 1 episode of angioedema during their lifetime. [43, 26]

Approximately 40-50% of patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria have angioedema, and about 10% have angioedema alone. [13, 14] Up to 1% of the population has chronic urticaria. [43] With these data in mind, up to 0.5% of the population is estimated to have chronic or recurrent angioedema.

It is likely that the great majority of cases of chronic or recurrent angioedema are idiopathic. [43, 26] HAE has an estimated prevalence of 1:10,000 to 1:50,000. [48] The prevalence of AAE is very low; until 2006, only about 136 cases had been reported in the literature. [29] The reported incidence of ACE inhibitor–induced angioedema ranges from 0.1% to 6%. [30]

International statistics

International occurrence rates are believed to be similar to those reported in the United States. However, in a Danish population survey, the lifetime prevalence of angioedema was 7.4%, and approximately 50% of cases were chronic angioedema (non-HAE). [35] In this study, 35.5% of angioedema patients had urticaria. The basis for the inconsistency between these findings and those of other studies is not clear.

Age-related demographics

Angioedema can affect people of all ages. Persons who are predisposed to angioedema have an increase in frequency of attacks after adolescence, with the peak incidence in the third decade of life. There is a continuous increase in the rate of hospital admissions for angioedema (3.0% per year). [14] The rate of hospitalization is highest in persons aged 65 years and older. [14]

Allergic reactions to food are more common in children. For patients with HAE, the onset of symptoms is often around puberty. The average age for angioedema induced by ACE inhibitors is 60 years. IAE is more common among persons aged 30-50 years than among other age groups. [43]

Sex-related demographics

Estrogen may exacerbate certain forms of angioedema. In HAE, affected women tend to have more frequent attacks and run more severe clinical courses. Oral contraceptives containing estrogen are often linked to exacerbation of swelling attacks. Chronic idiopathic angioedema is more common in females than in males. [43] Other types of angioedema do not show a strong sex preponderance.

Race-related demographics

No specific racial predilection exists for angioedema. However, black individuals are more susceptible to angioedema induced by ACE inhibitors. Compared with white persons, the adjusted relative risk for black persons is about 3.0 to 4.5. [30] Other forms of angioedema have no clear association between race and the disease frequency or severity.

Prognosis

The prognosis for patients with angioedema depends on the etiology and varies as follows:

-

Angioedema with identifiable causes – If the trigger(s) can be identified and avoided, angioedema can be prevented

-

Angioedema without identifiable causes – There is a tremendously variable clinical course, ranging from mild to severe and a few days to many years; the response to conventional treatment is less unpredictable

-

HAE – Lifelong treatment is often required

-

AAE – Outcome depends on the treatment of underlying lymphoproliferative or autoimmune disorders

Patient Education

Individuals with allergies to food, venom, or medications need to be educated regarding allergen avoidance. Patients must also be educated regarding the indications for and proper technique of epinephrine autoinjector use and the need to seek further medical assistance afterward.

For patient education information, see the Allergies Center and the Skin Conditions and Beauty Center, as well as Hives and Angioedema, Severe Allergic Reaction (Anaphylactic Shock), Food Allergy, and Drug Allergy.

Other recommended Websites include the following:

-

Food Allergy Research and Education (FARE) (formerly Food Allergy and Anaphylaxis Network [FAAN])

-

Photographic documentation of swelling.

-

Bradykinin production and metabolism.

-

Classification of angioedema without urticaria based on clinical or etiopathologic features. AAE = acquired angioedema; ACEI = angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; HAE = hereditary angioedema; Specific triggers = food, drug, insect bite, environmental allergen, or other physical stimulus. Based on data from Zingale LC, Beltrami L, Zanichelli A, et al. Angioedema without urticaria: a large clinical survey. CMAJ. Oct 24 2006; 175(9): 1065–70.

-

Angioedema secondary to angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors.

-

Types of angioedema.

-

Pathways for production of prostaglandins and leukotrine from mobilized arachidonic acid.

Tables

What would you like to print?

- Overview

- Presentation

- DDx

- Workup

- Treatment

- Medication

- Medication Summary

- Alpha/Beta-Adrenergic Agonists

- Antihistamines, 1st-Generation

- Antihistamines, 2nd Generation

- Histamine H2 Antagonists

- Leukotriene Receptor Antagonists

- Tricyclic Antidepressants

- Corticosteroids

- Androgens

- Antifibrinolytic Agents

- Immunomodulators

- Monoclonal Antibodies, Anti-asthmatics

- Show All

- Questions & Answers

- Media Gallery

- References