Practice Essentials

Influenza, one of the most common infectious diseases, is a highly contagious airborne disease that occurs in seasonal epidemics and manifests as an acute febrile illness with variable degrees of systemic symptoms, ranging from mild fatigue to respiratory failure and death. Influenza causes significant loss of workdays, human suffering, and mortality.

Preliminary in-season burden estimates for the 2022-2023 flu season were updated for the final time this season on May 26, 2023. An estimated 19,000 to 58,000 deaths have been attributed to influenza since October 2022. The CDC documented that seasonal influenza was responsible for 5,000 to 14,000 deaths during the 2021-2022 season. [1] Mortality was highest in infants and elderly persons.

Signs and symptoms

The presentation of influenza virus infection varies, but it usually includes many of the following signs and symptoms:

-

Fever

-

Sore throat

-

Myalgias

-

Frontal or retro-orbital headache

-

Nasal discharge

-

Weakness and severe fatigue

-

Cough and other respiratory symptoms

-

Tachycardia

-

Red, watery eyes

The incubation period of influenza is 2 days on average but may range from 1 to 4 days. Aerosol transmission may occur 1 day before the onset of symptoms [2] ; thus, it may be possible for transmission to occur via asymptomatic persons or persons with subclinical disease, who may be unaware that they have been exposed to the infection. [3, 4]

See Presentation for more detail.

Diagnosis

Influenza traditionally has been diagnosed on the basis of clinical criteria, but rapid diagnostic tests, which have a high degree of specificity but only moderate sensitivity, are becoming more widely used. The gold standard for diagnosing influenza A and B is a viral culture of nasopharyngeal samples or throat samples. In elderly or high-risk patients with pulmonary symptoms, perform chest radiography to exclude pneumonia.

Avian influenza

Avian influenza (H5N1) is rare in humans in developed countries. Unless advised by the CDC or regional health departments, clinicians do not routinely need to test for avian influenza.

See 12 Travel Diseases to Consider Before and After the Trip, a Critical Images slideshow, to help identify and manage infectious travel diseases.

See Workup for more detail.

Management

Prevention

Prevention of influenza is the most effective management strategy. Influenza A and B vaccine is administered each year before flu season. The CDC analyzes the vaccine subtypes each year and makes any necessary changes for the coming season on the basis of worldwide trends.

Traditionally, the vaccine was trivalent (ie, designed to provide protection against three viral subtypes, generally an A-H1, an A-H3, and a B). The first quadrivalent vaccines, which provide coverage against an additional influenza B subtype, were approved in 2012 and were made available for the 2013-2014 flu season. [5, 6] For the 2021-2022 influenza season, all flu vaccines are expected to be quadrivalent.

The FDA has approved a vaccine for H5N1 influenza. It is available only to government agencies and for stockpiles. [7] The following are influenza vaccine recommendations by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices [8] :

-

In the Northern Hemisphere, all persons aged 6 months or older should receive influenza vaccine annually by the end of October, if possible. Influenza vaccination should not be delayed to procure a specific vaccine preparation if an appropriate one is already available.

-

The approved age indication for the cell culture-based inactivated influenza vaccine, ccIIV4 [Flucelvax Quadrivalent], has been lowered to children ≥2 years

-

Those with a history of egg allergy who have experienced only hives after exposure to egg should receive influenza vaccine. A previous severe allergic reaction to any egg-based IIV, LAIV, or RIV of any valency is a precaution to administration of ccIIV4. A previous severe allergic reaction to a previous dose of any egg-based IIV, ccIIV, or LAIV of any valency is a precaution to administration of RIV4.

-

Regardless of allergy history, all vaccines should be administered in settings in which personnel and equipment for rapid recognition and treatment of anaphylaxis are available.

Treatment

In the United States, the following prescription antiviral drugs have been approved for treatment and/or chemoprophylaxis of influenza and are active against recently circulating subtypes of influenza:

-

Baloxavir marboxil

-

Oseltamivir

-

Peramivir

-

Zanamivir

See Treatment and Medication for more detail.

Background

Influenza, one of the most common infectious diseases, is a highly contagious airborne disease that occurs in seasonal epidemics and manifests as an acute febrile illness with variable degrees of systemic symptoms, ranging from mild fatigue to respiratory failure and death. Influenza causes significant loss of workdays, human suffering, and mortality.

Although the seasonal strains of influenza virus that circulate in the annual influenza cycle constitute a substantial public health concern, far more lethal influenza strains than these have emerged periodically. These deadly strains produced three global pandemics in the last century, the worst of which occurred in 1918. Called the Spanish flu (though cases appeared earlier in the United States and elsewhere in Europe), this pandemic killed an estimated 20 to 50 million persons, with 549,000 deaths in the United States alone. [9]

Influenza also infects a variety of animal species. Some of these influenza strains are species-specific, but new strains may spread from other animals to humans (see Pathophysiology). The term avian influenza, in this context, refers to zoonotic human infection with an influenza strain that primarily affects birds. Swine influenza refers to infections from strains derived from pigs. The 2009 influenza pandemic was a recombinant influenza involving a mix of swine, avian, and human gene segments (see H1N1 Influenza [Swine Flu]).

The signs and symptoms of influenza overlap with those of many other viral upper respiratory tract infections (URIs). A number of viruses, including human parainfluenza virus, adenoviruses, enteroviruses, and paramyxoviruses, may initially cause influenzalike illness. The early presentation of mild or moderate cases of flavivirus infections (eg, dengue) may initially mimic influenza. For example, some cases of West Nile fever acquired in New York in 1999 were clinically misdiagnosed as influenza. [3] (See DDx.)

When influenza viruses are circulating in the community, clinicians can often diagnose influenza on the basis of clinical criteria alone (see Presentation). Rapid diagnostic tests for influenza that can provide results within 30 minutes can help confirm the diagnosis.

It should be kept in mind, however, that these rapid tests have limited sensitivities and predictive values; false-negative results are common, especially when influenza activity is high, and false-positive results can also occur, especially when influenza activity is low. [10] Nevertheless, influenza virus testing may be considered if the results will change the clinical care of the patient (especially if the patient is hospitalized or has a high-risk condition) or influence the care of other patients. [10]

The gold standard for confirming influenza virus infection is reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) testing or viral culture of nasopharyngeal or throat secretions. However, culture may require 3 to 7 days, yielding results long after the patient has left the clinic, office, or emergency department, and well past the time when drug therapy could be efficacious.

Prevention of influenza is the most effective strategy. Each year in the United States, a vaccine that contains antigens from the strains most likely to cause infection during the winter flu season is produced. The vaccine provides reasonable protection against immunized strains, becoming effective 10 to 14 days after administration. Antiviral agents are also available that can prevent some cases of influenza; when given after the development of influenza, they can reduce the duration and severity of illness.(See Treatment.)

For information on influenza in children, see Pediatric Influenza. For patient education information, see Colds, Flu in Adults, and Flu in Children.

Pathophysiology

Influenza viruses are enveloped, negative-sense, single-stranded RNA viruses of the family Orthomyxoviridae. The core nucleoproteins are used to distinguish the three types of influenza viruses: A, B, and C. Influenza A viruses cause most human and all avian influenza infections. The RNA core consists of eight gene segments surrounded by a coat of 10 (influenza A) or 11 (influenza B) proteins. Immunologically, the most significant surface proteins include hemagglutinin (H) and neuraminidase (N).

Hemagglutinin and neuraminidase are critical for virulence, and they are major targets for the neutralizing antibodies of acquired immunity to influenza. Hemagglutinin binds to respiratory epithelial cells, allowing cellular infection. Neuraminidase cleaves the bond that holds newly replicated virions to the cell surface, permitting the infection to spread. [11]

Major typing of influenza A occurs through identification of both H and N proteins. Seventeen H and nine N types have been identified. All hemagglutinins and neuraminidases infect wild waterfowl, and the various combinations of H and N yield 144 potential subtypes of influenza.

The hemagglutinin and neuraminidase variants are used to identify influenza A virus subtypes. For example, influenza A subtype H3N2 expresses hemagglutinin 3 and neuraminidase 2. The most common subtypes of human influenza virus identified to date contain only hemagglutinins 1, 2, and 3 and neuraminidases 1 and 2. H3N2 and H1N1 are the most common prevailing influenza A subtypes that infect humans. Each year, the trivalent vaccine used worldwide contains influenza A strains from H1N1 and H3N2, along with an influenza B strain. The quadrivalent vaccine contains an additional influenza B strain.

Because the viral RNA polymerase lacks error-checking mechanisms, the year-to-year antigenic drift is sufficient to ensure that there is a significant susceptible host population each year. However, the segmented genome also has the potential to allow reassortment of genome segments from different strains of influenza in a coinfected host.

Influenza A is a genetically labile virus, with mutation rates as high as 300 times that of other microbes. [12] Changes in its major functional and antigenic proteins occur by means of two well-described mechanisms: antigenic drift and antigenic shift.

Antigenic drift is the process by which inaccurate viral RNA polymerase frequently produces point mutations in certain error-prone regions in the genes. These mutations are ongoing, and they are responsible for the ability of the virus to evade annually acquired immunity in humans. Drift can also alter the virulence of the strain. Drift occurs within a set subtype (eg, H2N2). For example, AH2N2 Singapore 225/99 may reappear with a slightly altered antigen coat as AH2N2 New Delhi 033/01.

Antigenic shift is less frequent than antigenic drift. In a shift event, influenza genes between two strains are reassorted, presumably during coinfection of a single host. Segmentation of the viral genome, which consists of 10 genes on eight RNA molecules, facilitates genetic reassortment. Because pigs have been susceptible to both human and avian influenza strains, many experts believe that combined swine and duck farms in some parts of Asia may have facilitated antigenic shifts and the evolution of previous pandemic influenza strains.

The reassortment of an avian strain with a mammalian strain may produce a chimeric virus that is transmissible between mammals; such mutation products may contain H or N proteins that are unrecognizable to the immune systems of mammals. This antigenic shift results in a much greater population of susceptible individuals in whom more severe disease is possible.

Such an antigenic shift can result in a virulent strain of influenza that possesses the triad of infectivity, lethality, and transmissibility and can cause a pandemic. Three major influenza pandemics have been recorded:

-

The Spanish influenza pandemic of 1918 (H1N1)

-

The pandemic of 1957 (H2N2)

-

The pandemic of 1968 (H3N2)

Smaller outbreaks occurred in 1947, 1976, 1977, and 2009.

Transmission and infection

Transmission of influenza from poultry or pigs to humans appears to occur predominantly as a result of direct contact with infected animals. The risk is especially high during slaughter and preparation for consumption; eating properly cooked meat poses no risk. Avian influenza can also be spread through exposure to water and surfaces contaminated by bird droppings. [13]

Influenza viruses spread from human to human via aerosols created when an infected individual coughs or sneezes. Infection occurs after an immunologically susceptible person inhales the aerosol. If not neutralized by secretory antibodies, the virus invades airway and respiratory tract cells.

On April 18, 2024, the World Health Organization (WHO) published a global technical consultation report that introduced updated terminology for pathogens that are transmitted through the air. These include those that cause COVID-19, influenza, measles, Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS), severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), and tuberculosis.

During 2021-2023, the WHO collaborated with experts from various disciplines and specialties as well as Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention; Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention; European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control; and United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [14]

Their work “addressed a lack of common terminology” regarding transmission of pathogens through the air that highlighted issues associated with the term “airborne transmission.”

The groups reached consensus on the term ‘infectious respiratory particles,’ which describes pathogens of various particle sizes that can be spread through the air at short and long ranges. “Transmission through the air” may be used as an umbrella term to describe spread of IRPs through the air by either airborne transmission or direct deposition modes.

Once the virus is within host cells, cellular dysfunction and degeneration occur, along with viral replication and release of viral progeny. As in other viral infections, systemic symptoms result from release of inflammatory mediators.

The incubation period of influenza ranges from 1 to 4 days. Aerosol transmission may occur 1 day before the onset of symptoms [2] ; thus, it may be possible for transmission to occur via asymptomatic persons or persons with subclinical disease, who may be unaware that they have been exposed to the disease. [3, 4, 15]

Viral shedding

Viral shedding occurs at the onset of symptoms or just before the onset of illness (0-24 hours) and continues for 5 to 10 days. Young children may shed virus longer, placing others at risk of contracting infection. In highly immunocompromised persons, shedding may persist for weeks to months. [15]

H5N1 avian influenza

To date, avian influenza (H5) remains a zoonosis. The vast majority of cases of avian influenza have been acquired from direct contact with live poultry, with no sustained human-to-human transmission. Hemagglutinin type 5 attaches well to avian respiratory cells and thus spreads easily among avian species. However, attachment to human cells and resultant infection is more difficult.

Avian viruses tend to prefer sialic acid alpha(2-3) galactose, which, in humans, is found in the terminal bronchi and alveoli. Conversely, human viruses prefer sialic acid alpha(2-6) galactose, which is found on epithelial cells in the upper respiratory tract. [16] Although this results in a more severe respiratory infection, it probably explains why few, if any, definite human-to-human transmissions of avian influenza have been reported: infection of the upper airways is probably required for efficient spread via coughing and sneezing.

Most human deaths from bird flu have occurred in Indonesia. Sporadic outbreaks among humans have continued elsewhere, including China, Egypt, Thailand, and Cambodia. [17]

In theory, however, mutation of the hemagglutinin protein through antigenic drift could result in a virus capable of binding to upper and lower respiratory epithelium, creating a strain that is easily transferred from human to human and thus could cause a worldwide pandemic.

Etiology

Influenza results from infection with one of three basic types of influenza virus: A, B, or C. Influenza A is generally more pathogenic than influenza B. Epidemics of influenza C have been reported, especially in young children. [18] Influenza viruses are classified within the family Orthomyxoviridae.

In the United States, influenza A(H3N2) was the predominant strain during the 2021-2022 flu season.

Avian influenza (ie, human infection with avian H5N1 influenza virus) is transmitted primarily through direct contact with diseased or deceased birds infected with the virus. Contact with excrement from infected birds or contaminated surfaces or water are also considered mechanisms of infection. Close and prolonged contact of a caregiver with an infected person is believed to have resulted in at least one case. Other specific risk factors are not apparent, given the few cases to date.

Epidemiology

In tropical areas, influenza occurs throughout the year. In the Northern Hemisphere, the influenza season typically starts in early fall, peaks in mid-February of the following year, and ends in the late spring. The duration and severity of influenza epidemics vary, however, depending on the virus subtype involved.

The WHO estimates that 1 billion influenza cases, 3 to 5 million severe cases, and 290,000 to 650,000 influenza-related respiratory deaths occur each year worldwide. [19] In the United States, individual cases of seasonal flu and flu-related deaths in adults are not reportable illnesses; consequently, mortality is estimated by using statistical models. [1]

The CDC estimates that flu-associated deaths in the United States ranged from about 3000 to 49,000 annually between 1976 and 2006. The CDC notes that the often-cited figure of 36,000 annual flu-related deaths was derived from years when the predominant virus subtype was H3N2, which tends to be more lethal than H1N1. [1]

Unlike adult flu-related deaths, pediatric flu-related deaths are reportable in the United States. (See Pediatric Influenza.) For the 2019-2020 influenza season, the CDC reports an estimated 35 million influenza-associated illnesses, 16 million influenza-related medical visits, 380,000 flu-associated hospitalizations, and 20,000 influenza-related deaths. A total of 486 children aged 0 months to 17 years died during the 2019-2020 influenza season. [1]

The following statistics are offered for comparison:

-

The 1918 H1N1 influenza pandemic caused 500,000-700,000 deaths in the United States—almost 200,000 of them in October 1918 alone—and an estimated 30-40 million deaths worldwide, mostly among people aged 15-35 years

-

The 1957 H2N2 influenza pandemic (Asian flu) caused an estimated 70,000 deaths in the United States and 1-2 million fatalities worldwide

-

The 1968 H3N2 influenza pandemic (Hong Kong flu) caused an estimated 34,000 deaths in the United States and 700,000 to 1 million fatalities worldwide

In contrast to typical influenza seasons, the 2009-2010 influenza season was affected by the H1N1 (“swine flu”) influenza epidemic, the first wave of which hit the United States in the spring of 2009, followed by a second, larger wave in the fall and winter; activity peaked in October and then quickly declined to below baseline levels by January 2010, but small numbers of cases were reported through the spring and summer of 2010. [20]

In addition, the effect of H1N1 influenza across the lifespan differed from that of typical influenza. Disease was more severe among people younger than 65 years than in nonpandemic influenza seasons, with significantly higher pediatric mortality and higher rates of hospitalizations in children and young adults. Of the 477 reported H1N1-associated deaths from April to August 2009, 36 were in children younger than 18 years; 67% of those children had one or more high-risk medical conditions. [20]

No cases of the highly pathogenic H5N1 influenza have been reported in humans or birds in the United States. Frequently updated information on H5N1 avian influenza cases and pandemic flu preparedness is available from the CDC. [21] Two case reports describe humans infected with another avian influenza virus, H7N2, one in Virginia in 2002 and the other in New York in 2003. The patients had no characteristic symptoms, but the first had positive serologic results and the second had mild respiratory symptoms.

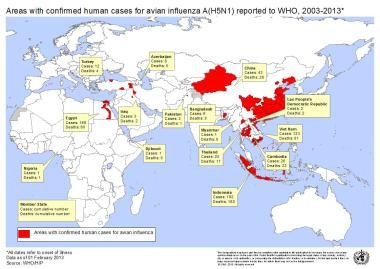

As of 2021, 862 cases of avian influenza had been reported by the World Health Organization (WHO) worldwide, with 455 deaths. [17] Reporting from areas with poor access to health care may be limited to clinically severe cases; illness that does not fulfill WHO diagnostic criteria is not reported. [22]

Most cases have been in eastern Asia; some cases have been reported in Eastern Europe and North Africa. Underreporting has been a concern, particularly in China, but the prevailing attitude about the need to suspect, test, and report cases of avian influenza is growing. In 2013, cases were reported in Cambodia, Vietnam, China, Egypt, and Bangladesh.

Prognosis

In patients without comorbid disease who contract seasonal influenza, the prognosis is very good. However, some patients have a prolonged recovery time and remain weak and fatigued for weeks. Mortality from seasonal influenza is highest in infants and the elderly.

The prognosis for patients with avian influenza is related to the degree and duration of hypoxemia. Cases to date have exhibited a 60% mortality; however, Wang et al suggest that this may be an overestimate stemming from the underreporting of mild cases. [22]

The risk for mortality from avian influenza depends on the degree of respiratory disease rather than on the bacterial complications (pneumonia). Mortality is significantly lower among patients cared for in more-developed nations. Little evidence is available regarding the long-term effects of disease among survivors.

Diabetes increases the risk for severe flu-related illness. In a cohort study of 166,715 individuals in Manitoba, Canada, Lau and colleagues found that adults with diabetes were at significantly greater risk for serious illness related to influenza compared with those without diabetes; this justifies guideline recommendations for influenza vaccination in this population. After controlling for age, sex, socioeconomic status, location of residence, comorbidities, and vaccination, adults with diabetes had a significant increase (6%) in all-cause hospitalizations associated with influenza (P = .044). Only 16% of the patients with diabetes in the cohort and 7% of the patients without diabetes had been vaccinated. [23, 24]

-

Countries where avian influenza has been reported. Image courtesy of the World Health Organization.

-

Colorized transmission electron micrograph shows avian influenza A H5N1 viruses (gold) grown in MDCK cells (green). Image courtesy of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

-

Transmission electron micrograph (original magnification 150,000X) shows ultrastructural details of an avian influenza A (H5N1) virion, a subtype of avian influenza A. Note the stippled appearance of the roughened surface of the proteinaceous coat encasing the virion. Image courtesy of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.