Practice Essentials

A hiatal hernia occurs when a portion of the stomach prolapses through the diaphragmatic esophageal hiatus. Most hiatal hernias are asymptomatic and are discovered incidentally, but rarely, a life-threatening complication may present acutely. The image below depicts a paraesophageal hiatal hernia.

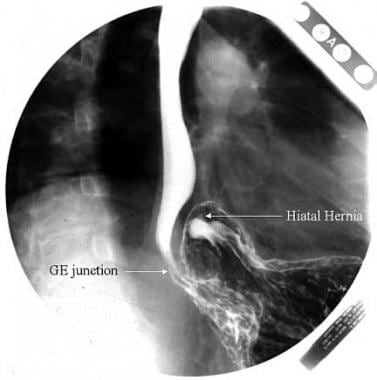

Hiatal Hernia. A paraesophageal hernia is seen on an upper gastrointestinal radiograph series. Note that the gastroesophageal (GE) junction remains below the diaphragm. Courtesy of David Y Graham, MD.

Hiatal Hernia. A paraesophageal hernia is seen on an upper gastrointestinal radiograph series. Note that the gastroesophageal (GE) junction remains below the diaphragm. Courtesy of David Y Graham, MD.

Signs and symptoms

Most people with hiatal hernias are asymptomatic. In a minority of individuals, hiatal hernias may predispose to reflux or worsen existing reflux.

Complications of hiatal hernia may include the following:

-

Intermittent bleeding from associated esophagitis, erosions (Cameron ulcers), or a discrete esophageal ulcer, leading to iron-deficiency anemia

-

Incarcerated hiatal hernia (rare; observed only with paraesophageal hernia)

The physical examination usually is unhelpful. Certain conditions may predispose to the development of hiatal hernia, including the following:

-

Muscle weakening and loss of elasticity with age

-

Pregnancy

-

Obesity

-

Abdominal ascites

Diaphragmatic hernias may be congenital or acquired. Acquired hiatal hernias are divided further into nontraumatic (more common) and traumatic hernias. Nontraumatically acquired hernias are divided yet further into two types: (1) sliding hiatal hernia and (2) paraesophageal hiatal hernia (a mixed variety is also possible).

See Presentation for more detail.

Diagnosis

The typical reason for evaluation is the presence of symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) or a chest radiograph suggesting a paraesophageal hernia.

A barium upper gastrointestinal series may yield the following findings:

-

Outpouching of barium at the lower end of the esophagus

-

A wide hiatus through which gastric folds are seen in continuum with those in the stomach

-

Occasionally, free reflux of barium

A barium study also helps distinguish a sliding from a paraesophageal hernia.

Upper GI endoscopy may be performed for the following purposes:

-

To diagnose hiatal hernia (though this is actually incidental)

-

To diagnose complications such as erosive esophagitis, ulcers in the hiatal hernia, Barrett esophagus, or tumor

-

To permit biopsy of any abnormal or suspicious area

See Workup for more detail.

Management

When symptoms are due to GERD, treatment goals include the following:

-

Prevention of reflux of gastric contents

-

Improved esophageal clearance

-

Reduction in acid production

In the majority of patients, these goals are achieved by means of a combination of the following:

-

Modifying lifestyle factors

-

Neutralizing acid or inhibiting acid-producing mechanisms

-

Enhancing esophageal and gastric motility

If iron-deficiency anemia occurs, it usually responds well to proton-pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy.

Surgical treatment involves removing the hernia sac and closing the abnormally wide esophageal hiatus. It is necessary only in the very few patients who have complications of GERD despite aggressive PPI treatment. Potential surgical candidates include the following:

-

Young patients with severe or recurrent complications of GERD (eg, strictures, ulcers, or bleeding) who cannot afford lifelong PPI treatment or prefer to avoid long-term pharmacotherapy

-

Patients with pulmonary complications (eg, asthma, recurrent aspiration pneumonia, chronic cough, or hoarseness linked to reflux disease)

The three major types of surgical procedures that may be considered are as follows:

-

Nissen fundoplication (or a variant, the Toupet procedure)

-

Belsey fundoplication

-

Hill repair

See Treatment and Medication for more detail.

Background

A hiatal hernia occurs when a portion of the stomach prolapses through the diaphragmatic esophageal hiatus (see the images below). Although the existence of hiatal hernia has been described in earlier medical literature, it has come under scrutiny only in the last century or so because of its association with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and its complications. There is also an association between obesity and the presence of hiatal hernia.

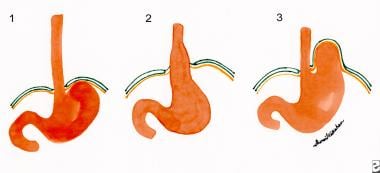

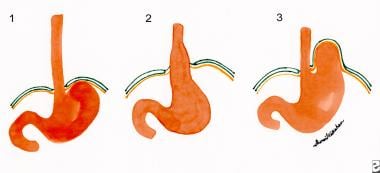

Hiatal Hernia. Figure 1 shows the normal relationship of the gastroesophageal (GE) junction, stomach, esophagus, and diaphragm. Figure 2 shows a sliding hiatal hernia, in which the stomach immediately below the GE junction is seen to prolapse through the diaphragmatic hiatus into the chest. Figure 3 shows a paraesophageal hernia in which the cardia or fundus of the stomach prolapses through the diaphragmatic hiatus, leaving the GE junction within the esophageal cavity.

Hiatal Hernia. Figure 1 shows the normal relationship of the gastroesophageal (GE) junction, stomach, esophagus, and diaphragm. Figure 2 shows a sliding hiatal hernia, in which the stomach immediately below the GE junction is seen to prolapse through the diaphragmatic hiatus into the chest. Figure 3 shows a paraesophageal hernia in which the cardia or fundus of the stomach prolapses through the diaphragmatic hiatus, leaving the GE junction within the esophageal cavity.

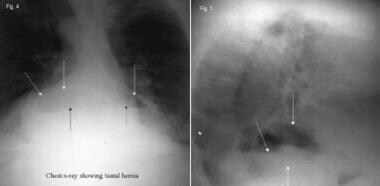

Hiatal Hernia. These anteroposterior (left) and lateral views (right) on a chest radiograph showing a large hiatal hernia. Courtesy of David Y Graham, MD.

Hiatal Hernia. These anteroposterior (left) and lateral views (right) on a chest radiograph showing a large hiatal hernia. Courtesy of David Y Graham, MD.

By far, most hiatal hernias are asymptomatic and are discovered incidentally. On rare occasion, a life-threatening complication, such as gastric volvulus or strangulation, may present acutely. See the following image.

Pathophysiology

The esophagus passes through the diaphragmatic hiatus in the crural part of the diaphragm to reach the stomach. The diaphragmatic hiatus itself is approximately 2 cm in length and chiefly consists of musculotendinous slips of the right and left diaphragmatic crura arising from either side of the spine and passing around the esophagus before inserting into the central tendon of the diaphragm. The size of the hiatus is not fixed, but narrows whenever intra-abdominal pressure rises, such as when lifting weights or coughing. [1]

The lower esophageal sphincter (LES) is an area of smooth muscle approximately 2.5-4.5 cm in length. The upper part of the sphincter normally lies within the diaphragmatic hiatus, while the lower section normally is intra-abdominal. At this level, the visceral peritoneum and the phrenoesophageal ligament cover the esophagus. The phrenoesophageal ligament is a fibrous layer of connective tissue arising from the crura, and it maintains the LES within the abdominal cavity. The A-ring is an indentation sometimes seen on barium studies, and it marks the upper part of the LES. Just below this is a slightly dilated part of the esophagus, forming the vestibule. A second ring, the B-ring, may be seen just distal to the vestibule, and it approximates the Z-line or squamocolumnar junction. The presence of a B-ring confirms the diagnosis of a hiatal hernia. Occasionally, the B-ring also is called the Schatzki ring.

Any sudden increase in intra-abdominal pressure also acts on the portion of the LES below the diaphragm to increase the sphincter pressure. An acute angle, the angle of His, is formed between the cardia of the stomach and the distal esophagus and functions as a flap at the gastroesophageal junction and helps prevent reflux of gastric contents into the esophagus (see the image below).

Hiatal Hernia. Figure 1 shows the normal relationship of the gastroesophageal (GE) junction, stomach, esophagus, and diaphragm. Figure 2 shows a sliding hiatal hernia, in which the stomach immediately below the GE junction is seen to prolapse through the diaphragmatic hiatus into the chest. Figure 3 shows a paraesophageal hernia in which the cardia or fundus of the stomach prolapses through the diaphragmatic hiatus, leaving the GE junction within the esophageal cavity.

Hiatal Hernia. Figure 1 shows the normal relationship of the gastroesophageal (GE) junction, stomach, esophagus, and diaphragm. Figure 2 shows a sliding hiatal hernia, in which the stomach immediately below the GE junction is seen to prolapse through the diaphragmatic hiatus into the chest. Figure 3 shows a paraesophageal hernia in which the cardia or fundus of the stomach prolapses through the diaphragmatic hiatus, leaving the GE junction within the esophageal cavity.

The gastroesophageal junction acts as a barrier to prevent reflux of contents from the stomach into the esophagus by a combination of mechanisms forming the antireflux barrier. The components of this barrier include the diaphragmatic crura, the LES baseline pressure and intra-abdominal segment, and the angle of His. The presence of a hiatal hernia compromises this reflux barrier not only in terms of reduced LES pressure but also reduced esophageal acid clearance. Patients with hiatal hernias also have longer transient LES relaxation episodes particularly at night time. These factors increase the esophageal mucosa acid contact time predisposing to esophagitis and related complications.

Etiology

Predisposing factors include the following:

-

Muscle weakening and loss of elasticity as people age is thought to predispose to hiatus hernia, based on the increasing prevalence in older people. With decreasing tissue elasticity, the gastric cardia may not return to its normal position below the diaphragmatic hiatus following a normal swallow. Loss of muscle tone around the diaphragmatic opening also may make it more patulous.

-

Hiatal hernias are more common in women. This may relate to the intra-abdominal forces exerted in pregnancy.

-

Burkitt et al suggest that the Western, fiber-depleted diet leads to a state of chronic constipation and straining during bowel movement, which might explain the higher incidence of this condition in Western countries.

-

Obesity predisposes to hiatus hernia because of increased abdominal pressure.

-

Conditions such as chronic esophagitis may cause shortening of the esophagus by causing fibrosis of the longitudinal muscles and, therefore, predispose to hiatal hernia. However, which comes first, the hiatal hernia worsening the reflux or the reflux-induced shortening of the esophagus, remains unknown.

-

The presence of abdominal ascites also is associated with hiatal hernias.

-

Diaphragmatic hernias may be congenital or acquired. Acquired hiatal hernias are divided further into nontraumatic and traumatic hernias. The most common types of hernias are those acquired in a nontraumatic fashion. Hernias acquired in a nontraumatic fashion are divided into two types, (1) sliding hiatal hernia and (2) paraesophageal hiatal hernia. A mixed variety with coexisting sliding and paraesophageal components is possible.

Sliding hiatal hernia by far is the most common type of hiatal hernia. It occurs when the gastroesophageal junction, along with a portion of the stomach, migrates into the mediastinum through the esophageal hiatus (see the image below). The majority of patients with demonstrated hiatal hernias are asymptomatic. This type of hernia interferes with the reflux barrier mechanism in several ways. As the LES moves into the chest, it no longer is exposed to positive intra-abdominal pressure and, therefore, is less effective as a sphincter. In fact, the sphincter moves into an area of low pressure, which interferes with the sphincter activity. In addition, the widening hiatus affects the competence of the diaphragmatic crura. The angle of His is lost, making regurgitation of gastric contents more likely. These changes not only predispose to reflux of gastric contents into the esophagus, but also prolong the acid contact time with the epithelium of the esophagus.

Hiatal Hernia. Figure 1 shows the normal relationship of the gastroesophageal (GE) junction, stomach, esophagus, and diaphragm. Figure 2 shows a sliding hiatal hernia, in which the stomach immediately below the GE junction is seen to prolapse through the diaphragmatic hiatus into the chest. Figure 3 shows a paraesophageal hernia in which the cardia or fundus of the stomach prolapses through the diaphragmatic hiatus, leaving the GE junction within the esophageal cavity.

Hiatal Hernia. Figure 1 shows the normal relationship of the gastroesophageal (GE) junction, stomach, esophagus, and diaphragm. Figure 2 shows a sliding hiatal hernia, in which the stomach immediately below the GE junction is seen to prolapse through the diaphragmatic hiatus into the chest. Figure 3 shows a paraesophageal hernia in which the cardia or fundus of the stomach prolapses through the diaphragmatic hiatus, leaving the GE junction within the esophageal cavity.

In paraesophageal hernia, also called rolling-type hiatal hernia, the widened hiatus permits the fundus of the stomach to protrude into the chest, anterior and lateral to the body of the esophagus; however, the gastroesophageal junction remains below the diaphragm (see Figure 3 of the image above). This causes the stomach to rotate in a counter-clockwise direction. As the hiatus widens, increasing amounts of the greater curvature of the stomach and, sometimes, the gastric-colic omentum, follow. The fundus eventually comes to lie above the gastroesophageal junction, with the pylorus being pulled towards the diaphragmatic hiatus. In this type of hernia, the anatomic relation of the stomach to the lower end of the esophagus (angle of His) tends to remain unchanged, so gross acid reflux does not occur. There is about a 1% per year risk of urgent intervention in a 65 year old and patients should be made aware of this. [2] Few are completely asymptomatic, most patients have some (at least mild) obstructive or reflux symptoms; a few have GI bleeding from Cameron ulcers. Patients with symptoms impairing their quality of life should have surgery, which is usually laparoscopic.

Epidemiology

United States data

Hiatal hernias are more common in Western countries. The frequency of hiatus hernia increases with age, from 10% in patients younger than 40 years to 70% in patients older than 70 years.

International data

Burkitt et al suggest that the Western, fiber-depleted diet leads to a state of chronic constipation and straining during bowel movement, which could explain the higher incidence of this condition in Western countries. [3]

Sex- and age-related demographics

Hiatal hernias are more common in women than in men. This might relate to the intra-abdominal forces exerted in pregnancy.

Muscle weakening and loss of elasticity as people age is thought to predispose to hiatus hernia, based on the increasing prevalence in older people. With decreasing tissue elasticity, the gastric cardia may not return to its normal position below the diaphragmatic hiatus following a normal swallow. Loss of muscle tone around the diaphragmatic opening also may make it more patulous.

Morbidity/Mortality

Paraesophageal hernias generally tend to enlarge with time, and sometimes the entire stomach is found within the chest. The risk of these hernias becoming incarcerated, leading to strangulation or perforation, is approximately 5%. This complication is potentially lethal, and surgical intervention is necessary. Because of the high mortality associated with this condition, elective repair often is advised wherever a paraesophageal hernia is found. [4, 5]

Sihvo et al examined the mortality associated with adult paraesophageal hernia in a Finnish retrospective, population-based study. [4] Five hundred sixty-three patients received surgical intervention and 67 received conservative treatment for paraesophageal hernia. Death occurred in 32 patients, of whom 29 had concomitant diseases.

Of the 563 patients in the surgical group, the overall mortality was 2.7% (15 patients), of whom 3 died following elective repair. [4] Of the 67 patients in the conservative treatment group, 16.4% (11 patients) died; 13% (4 patients) of the deaths might have been avoided with elective surgical intervention. Of the 32 patients who died, over half had type III (16 patients; 50%) or type IV (9 patients; 28.1%) had hiatal hernias; 4 patients (12.5%) had had type II hiatal hernias, with the remaining 3 deceased having an unknown type. The causes of death were primarily from incarceration (24 patients; 75%), followed by surgical complications (6 patients; 18.8%) and bleeding ulcer (2 patients; 6.2%). [4]

Sihvo et al recommended of the paraesophageal hernia, at least in symptomatic patients, except for those at high surgical risk. [4]

In a Swiss study, Larusson et al investigated the predictive factors for postoperative morbidity and mortality in patients undergoing laparoscopic hernia repair. [5] Of 354 laparoscopic paraesophageal hernia repairs, age at 70 years or older was significantly associated with postoperative morbidity (24.4%) and mortality (2.4%) relative to those younger than 70 years (10.1% postoperative morbidity, P = 0.001; 0% mortality, P = 0.045). Similar age findings were noted with gastropexy but not with fundoplication. [5] In addition, high-risk patients had significantly higher morbidity but not mortality.

Larusson et al concluded that age, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score, and type of operation are significant predictive factors in patients undergoing laparoscopic paraesophageal hernia repair. [5] The investigators advised caution in balancing surgical indications with each patient's comorbidities, age, symptoms, and potentially life-threatening complications. [5]

Cardiac complications such as cardiac tamponade have been reported to occur following laparoscopic Nissen repair of large hiatal hernia. [6]

Patient Education

Educate patients about the potential for complications of each type of hernia, including the following:

-

Complications of the hernia itself: Paraesophageal hernia may strangulate.

-

Complications from reflux disease: Heartburn, strictures, Barrett esophagus, and esophageal cancer may occur in a minority of patients with hiatal hernias.

Instruct patients to seek medical attention if new symptoms develop or if GERD symptoms are poorly controlled.

For patient education resources, see the Digestive Disorders Center. Also see the patient education article Hiatal Hernia.

-

Hiatal Hernia. Figure 1 shows the normal relationship of the gastroesophageal (GE) junction, stomach, esophagus, and diaphragm. Figure 2 shows a sliding hiatal hernia, in which the stomach immediately below the GE junction is seen to prolapse through the diaphragmatic hiatus into the chest. Figure 3 shows a paraesophageal hernia in which the cardia or fundus of the stomach prolapses through the diaphragmatic hiatus, leaving the GE junction within the esophageal cavity.

-

Hiatal Hernia. These anteroposterior (left) and lateral views (right) on a chest radiograph showing a large hiatal hernia. Courtesy of David Y Graham, MD.

-

Hiatal Hernia. This barium study shows a sliding hiatal hernia: The gastric folds can be seen extending above the diaphragm. GE = gastroesophageal. Courtesy of David Y Graham, MD.

-

Hiatal Hernia. A paraesophageal hernia is seen on an upper gastrointestinal radiograph series. Note that the gastroesophageal (GE) junction remains below the diaphragm. Courtesy of David Y Graham, MD.

-

Hiatal Hernia. A paraesophageal hernia is seen on a barium upper gastrointestinal radiograph series. The mucosal folds are seen going up into the chest, next to the esophagus. GE = gastroesophageal. Courtesy of David Y Graham, MD.

-

Hiatal Hernia. This image is a barium radiograph view of a large paraesophageal hernia. GE = gastroesophageal. Courtesy of David Y Graham, MD.

-

Hiatal Hernia. This barium radiograph shows a large paraesophageal hernia in which the entire stomach is seen in the chest cavity. Courtesy of David Y Graham, MD.

-

Hiatal Hernia. These barium studies show gastric volvulus as the herniated stomach undergoes rotation. This situation requires surgical intervention. Courtesy of David Y Graham, MD.

-

Hiatal Hernia. A retrograde view of a hiatal hernia seen at endoscopy shows the gastric folds to the left of the scope shaft extending up into the hernia. Courtesy of David Y Graham, MD.

-

Hiatal Hernia. Inderpal S Sarkaria, MD, discusses the options for paraesophageal hernia repair. Courtesy of Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center.

-

Hiatal Hernia. This image shows a Linx device in place during laparoscopic surgery. Courtesy of Shawn S Groth, MD, MS, FACS.

-

Hiatal Hernia. This image demonstrates a Linx device in place on x-ray. Courtesy of Shawn S Groth, MD, MS, FACS.