Practice Essentials

Phimosis

Phimosis is defined as the inability of the prepuce (foreskin) to be retracted behind the glans penis in uncircumcised males. Depending on the situation, this condition may be considered either physiologic or pathologic. Physiologic, or congenital, phimosis is a normal condition of the newborn male. In 90% of cases, natural separation allows the foreskin to retract by age 3 years. However, phimosis persisting into late adolescence or early adulthood need not be considered abnormal.

The entity of pathologic, or true, phimosis is far less common and can affect children or adults. This is associated with cicatricial scarring of the prepuce that is often white in appearance. Phimosis may occur after circumcision if redundant inner prepuce slides back over the glans, with subsequent cicatricial scarring and contraction. Adult phimosis (ie, pathologic or true phimosis) may be caused by poor hygiene or an underlying medical condition (eg, diabetes mellitus).

Uncomplicated pathologic phimosis is usually amenable to conservative medical treatment. Failure of medical treatment warrants surgical intervention, usually in the traditional form of a circumcision or preputioplasty.

Adult circumcision

Although phimosis is the most common indication for adult circumcision, [1] other reported indications include the following:

-

Balanitis without phimosis

-

Condyloma

-

Redundant foreskin

-

Disease prophylaxis (eg, HIV infection)

-

Patient choice

Studies suggest that circumcised boys are at a lower risk of urinary tract infections (UTIs). To put this in perspective, the approximate likelihood of a UTI occurring in the first year of life is 1 in 100 in uncircumcised boys and 1 in 1000 in circumcised boys. [2] A lower risk of malignancy is also reported in studies of circumcised men, although the incidence is also rare in uncircumcised men. Of note, this decreased risk seems to be associated only with infant circumcision and not with adult procedures.

The theory that circumcision contributes to prevention of sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) was encouraged by a 19th-century report of lower rates of syphilis in Jewish men. Studies have demonstrated that human papillomavirus (HPV) infection, including oncogenic HPV infection, is more prevalent in uncircumcised men, regardless of demographics and sexual history. [3]

Citing a link between the intact prepuce and sexually transmitted infection, some authorities have gone as far as suggesting that circumcision protects against prostate cancer. [4] Additionally, controlled studies by Tobian et al have shown the efficacy of circumcision in reducing the incidence of herpes simplex virus type 2 infection, and a follow-up study suggested that it may protect female partners from acquisition in men already infected. [5, 6]

Meta-analysis of three randomized controlled trials in South Africa, [7] Kenya, [8] and Uganda [9] has demonstrated that circumcision decreases the risk of HIV infection among heterosexual men by nearly 60%. [10] Data from a mathematical model suggested that routine circumcision in southern sub-Saharan Africa could prevent 2 million HIV infections over 10 years. [11]

The results of theses studies led the World Health Organization (WHO) and Joint United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS to recommended the use of voluntary medical male circumcision (MMC) to fight the spread of HIV infection in countries with a low male circumcision prevalence rate and a high HIV prevalence rate. [12]

Analysis of population-based surveys conducted from 1999 through 2013 in 45 rural Uganda communities lent support to this initiative, with findings that MMC coverage increased from 19% to 39% with an associated decrease in HIV incidence from 1.25 to 0.84 per 100 person-years in males. [13] Further evaluation of these trials has shown no deleterious effects on male erectile function or sexual satisfaction, and 97.1% of female partners reported no change or improved sexual enjoyment after circumcision of their male partner. [14]

The results of the African randomized trials also sparked speculative interest in male circumcision to reduce HIV infection in the United States, especially in areas such as New York City. [15] Pask et al have suggested that the protective benefit of circumcision against HIV infection may result from removal of Langerhans cells and that enhanced keratinization conferred by topical estrogen may therefore represent an alternative to circumcision. [16]

Other indications for circumcision exist. Genital lichen sclerosus appears to be a disease generally restricted to uncircumcised males and is often cured by circumcision. [17] Additionally, removal of foreskin remnants has shown to be an effective modality in select patients with premature ejaculation. [18]

Buried penis

Buried penis is a true congenital disorder in which a penis of normal size lacks the proper sheath of skin and lies hidden beneath the integument of the abdomen, thigh, or scrotum. The literature, on occasion, also refers to this condition as a hidden or concealed penis.

This condition is usually identified in neonates or obese prepubertal boys; however, it can also be seen in adults and has been observed in both circumcised and uncircumcised individuals. Marginal cases may not be diagnosed until adulthood, when increased fat deposition accentuates the problem. In most congenital pediatric cases, the buried penis is self-limited. In untreated adults, however, the condition tends to worsen as the abdominal pannus continues to grow.

Other conditions to consider include the following:

-

Trapped penis is a condition in which the penis becomes inconspicuous secondary to a cicatricial scar, usually after overzealous circumcision.

-

Webbed penis is characterized by obscuration of the penile shaft by scrotal skin webs at the penoscrotal junction.

-

Micropenis (also known as microphallus) represents a penis less than 2 standard deviations below the mean in length when measured in the stretched state.

-

Diminutive penis is a penis that is small, malformed, or both secondary to epispadias, exstrophy, severe hypospadias, chromosomal abnormalities, or intersex conditions.

For patient education information, see the Men's Health Center, as well as Foreskin Problems and Circumcision FAQ.

Background

Circumcision

Circumcision is one of the earliest elective operations known to man. Historically, this procedure has been performed for various religious reasons, social reasons, or both. The practice is considered a commandment in Jewish law and a rule of cleanliness in Islam, although it is not mentioned in the Quran. Female circumcision, better termed female genital mutilation (FGM), has been practiced for centuries by some cultures but is an unacceptable practice and without medical benefit.

Potential psychological and surgical complications have led to closer scrutiny of routine neonatal circumcision. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) does not recommend routine neonatal circumcision but has concluded that the health benefits of newborn male circumcision outweigh the risks and justify access to this procedure for families who choose it. Specific benefits from male circumcision were identified for the prevention of urinary tract infections, acquisition of HIV, transmission of some sexually transmitted infections, and penile cancer. [19]

The American Urological Association (AUA) recommends that circumcision should be presented as an option for health benefits that include prevention of phimosis, paraphimosis, and balanoposthitis, and decreased risk for cancer of the penis. In addition, the AUA noted that for the first 3 to 6 months of life, the incidence of urinary tract infections is at least 10 times higher in uncircumcised than circumcised boys. [2]

Evidence suggests that infant circumcision seems to decrease the risk of penile cancer, [20] whereas later circumcision does not. Penile cancer is a rare disease in the United States, with an incidence of 1.5 per 100,000 males. In developing countries, the incidence is higher; the disease accounts for up to 10% of malignancies in some African and South American nations. Although primarily a disease of older men, penile cancer has been reported in children. The lowest incidence has been reported in Jews, with a similar incidence in Muslims; both groups have high rates of neonatal circumcision.

The main medical indication for circumcision in children is pathologic phimosis. Infants may present with paraphimosis if their parents have retracted the prepuce and failed to pull it forward thereafter. Reduction of the foreskin under sedation is almost always possible. However, in some situations, a dorsal slit or circumcision is required (see Paraphimosis).

In a prospective long-term study, 40% of boys treated for phimosis were found to have balanitis xerotica obliterans (BXO), which has been linked to the development of penile squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). [21] Although potent topical steroids may allow improvement and slow progression, total circumcision is the treatment of choice for BXO and may be curative.

Recurrent balanoposthitis, which affects 1% of boys, is also considered a relative indication for circumcision. However, this condition tends to be self-limited, and even if balanoposthitis is recurrent, preputioplasty and topical steroids represent alternatives to circumcision. [22, 23, 24, 25] In patients with balanoposthitis who are sufficiently troubled to warrant surgical intervention, circumcision is always curative.

Circumcision is generally not performed in children born prematurely or those with blood dyscrasias. It should not be performed in children with congenital penile anomalies such as the following:

-

Hypospadias

-

Epispadias

-

Chordee

-

Penile webbing

-

Buried penis

Adult circumcision for phimosis is described in textbooks dating from the early 19th century. Paraphimosis results from abuse or accident, not disease, of the foreskin and can be seen at any age. It represents the second most common indication for adult circumcision. Unrecognized chronic paraphimosis or delay in diagnosis may result in urinary retention or even penile autoamputation.

Other indications for circumcision that are less common include small preputial tumors, multiple preputial cysts or condylomas, and penile lymphedema. A reasonable case may be made for circumcising boys with vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) who suffer from urinary tract infections. In addition, the foreskin may be removed to perform a biopsy of lesions hidden under the prepuce or for definitive radiation therapy for penile cancer.

Occasions arise in which urethral instrumentation — in the form of a cystoscopy or Foley catheterization — is necessary. This may be quite problematic in an adult affected by severe phimosis. In such instances, an emergency bedside dorsal slit can be performed safely and expeditiously. After being discharged, the patient may proceed to undergo formal circumcision.

Buried Penis

The first description of the buried penis was in 1919 by Keyes. The first attempted surgical correction of this problem was by Schloss in 1959; in 1968, successful correction was performed in an adult by Glanz. Since then, numerous techniques to correct buried penis have been developed.

The primary reason that children are referred for correction of the buried penis is cosmesis. In the neonate, observation seems to be a viable option. Children younger than 3 years have a 58% chance of spontaneous resolution. Some pediatric urologists insist that this condition is a developmental stage that will resolve by puberty and feel that correction should therefore be deferred. Evidence has shown, however, that spontaneous resolution does not always occur. Also, in men and adolescents, measures such as diet and exercise are unlikely to be effective.

Others feel that, after age 3 years, buried penis requires correction. The primary reason cited is the importance of being able to void while standing during the period of toilet training. There are numerous other indications for repair. For example, a concealed penis can hamper proper hygiene, trap urine, and complicate voiding. This can lead to repeated infections, secondary phimosis, or even urinary retention. In addition, numerous investigators feel that children with buried penis are at risk for psychological and social trauma, even from an early age. Obese boys with a buried penis may be ostracized by their peers and withdraw socially. Surgery often relieves anxiety and may improve self-image.

In adults, buried penis tends to worsen over time as they accumulate more fat. The cicatricial scar does not loosen on its own over time. Urinary and sexual complications can greatly affect daily life. Therefore, surgery is likely necessary in these patients.

Relevant Anatomy

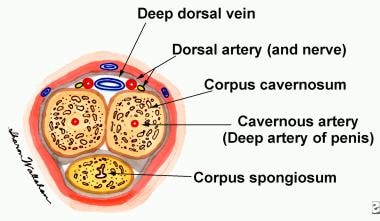

The penis is composed of paired corpora cavernosa, the crura of which are attached to the pubic arch, and the corpus spongiosum (see image below). The proximal portion of the corpus spongiosum is referred to as the bulb of the penis, and the glans represents the distal expansion. The urethra traverses the corpus spongiosum to exit at the meatus. The cavernosal bodies produce the male erection when they are engorged with blood.

The fascial layers of the penis are continuous with the fascial layers of the perineum and lower abdomen. Dartos fascia represents the superficial penile fascia. Deep to this lies the Buck fascia, which covers the tunica albuginea of the penile bodies. Proximally, the Buck fascia is in continuity with the suspensory ligament of the penis, which attaches to the symphysis pubis.

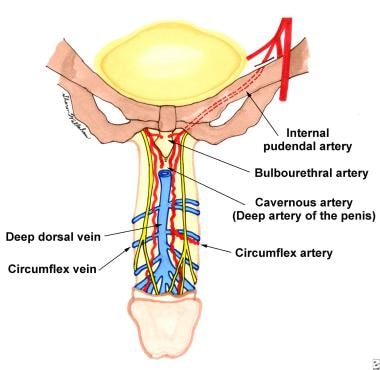

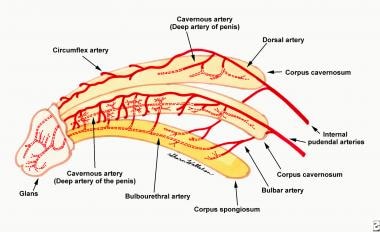

The penis is supplied by a superficial system of arteries that arise from the external pudendal arteries and a deep system of arteries that stem from the internal pudendal arteries (see images below). The superficial blood supply lies in the superficial penile fascia and supplies the penile skin and prepuce. The internal pudendal artery, which arises from the hypogastric artery, gives rise to the penile artery. The penile artery then gives rise to the bulbourethral artery, the urethral artery, and the cavernous artery (deep artery of the penis) before terminating as the dorsal artery of the penis.

The arterial blood supply of the penis arises from the internal pudendal artery. The internal pudendal artery gives off branches to the bulbar artery, cavernosal artery, and dorsal penile artery. The bulbar artery continues on as the bulbourethral artery to supply the urethra. The cavernosal artery gives rise to the helicine arteries that are end arteries. The dorsal artery of the penis gives branches off to the circumflex arteries.

The arterial blood supply of the penis arises from the internal pudendal artery. The internal pudendal artery gives off branches to the bulbar artery, cavernosal artery, and dorsal penile artery. The bulbar artery continues on as the bulbourethral artery to supply the urethra. The cavernosal artery gives rise to the helicine arteries that are end arteries. The dorsal artery of the penis gives branches off to the circumflex arteries.

Somatic nerve supply to the penis comes by way of the pudendal nerves, which eventually produce the dorsal nerves of the penis on each side. Although cutaneous innervation to the penis is primarily from branches of the pudendal nerve, the proximal portion is supplied by the ilioinguinal nerve after it leaves the superficial inguinal ring. The prepuce has somatosensory innervation by the dorsal nerve of the penis and branches of the perineal nerve. The glans is primarily innervated by free nerve endings and has poor fine-touch discrimination.

Pathophysiology

Phimosis

The foreskin of an uncircumcised child should not be forcefully retracted. This may result in significant bleeding, as well as glanular excoriation and injury. Consequently, dense fibrous adhesions may form during the healing process, leading to true pathologic phimosis.

Adult phimosis may be caused by repeated episodes of balanitis or balanoposthitis. Such infections are commonly due to poor personal hygiene (failure to regularly clean under the foreskin).

Phimosis may be a presenting symptom of early diabetes mellitus. When the residual urine of a patient with diabetes mellitus becomes trapped under the foreskin, the combination of a moist environment and glucose in the urine may lead to a proliferation of bacteria, with subsequent infection, scarring, and eventual phimosis.

Buried penis

The penis is properly formed by 16 weeks' gestation. Congenital buried penis is caused by a developmental anomaly in which the dartos fascia has not developed into the normal elastic configuration to allow the penile skin to move freely over the deeper tissues of the penile shaft. Instead, the dartos layer is inelastic, which prevents the forward extension of the penis and holds it buried under the pubis.

Other possible contributing factors to congenital buried penis include excess prepubic fat, scrotal webbing, deficient penile skin, loose skin, an abnormally low position at which the crura separate, abnormal attachments between the Buck fascia and the tunica albuginea, and insufficient attachment of dartos fascia and skin to the Buck fascia.

The pathophysiology of buried penis in adults differs from that in children and includes iatrogenically induced scar contracture with concurrent descent of the abdominal fat pad. Because the penis is suspended from the pubis by the suspensory ligament, it remains fixed, unlike the prepubic fat. As fat descends over the penis, excessive moisture and bacterial overgrowth may occur. Chronic infection may lead to skin maceration and more scar contracture, further aggravating the problem. In many children, this condition is self-limited. However, in adults, total body fat content typically increases with age, causing the buried penis to worsen over time.

Etiology

Phimosis

Physiologic phimosis is the rule in newborn males. Formation of the prepuce is complete by 16 weeks' gestation. The inner prepuce and glans penis share a common, fused mucosal epithelium at birth. This epithelium separates via desquamation over time as the proper hormonal and growth factors are produced. Thus, neonatal circumcision is a surgical treatment of normal anatomy.

Pathologic, or true, phimosis has several different etiologies. The most common cause is infection, such as posthitis, balanitis, or a combination of the two (balanoposthitis). Diabetes mellitus may predispose to such infections.

Adult circumcision is most commonly performed to correct phimosis. When circumcision is performed for phimosis, 25%-46% of removed foreskins are histologically normal. Other indications for adult circumcision include the following:

-

Infection without phimosis

-

Paraphimosis

-

Bowen disease

-

Carcinoma

-

Condylomas (warts)

-

Trauma

-

Religious or social reasons

-

Disease prophylaxis (eg, HIV infection)

-

Personal preference

Buried penis

Various etiologic factors have been proposed to explain congenital buried penis. Recent literature favors dysgenetic dartos tissue with abnormal attachments proximally and to the dorsal cavernosum. A prominent prepubic fat pad is also a common primary factor, in addition to dysgenetic dartos fascia. Secondary buried penis may be the result of an overzealous circumcision with subsequent cicatricial scar (trapped penis), a large hernia, or a hydrocele.

Adults with buried penis are commonly obese and often have a history of trauma or surgery. There is an observed association with diabetes mellitus, which may aggravate the pathologic process. Another additive factor in select patients includes the significant laxity of abdominal skin following gastric bypass. [26] Adults with this condition may have undergone abdominoplasty with overzealous release of attachments between the scarpa and dartos fasciae, penile-lengthening procedures, or other genitoinguinal surgeries.

Another possible cause of buried penis in the adult is genital lymphedema. This may be idiopathic, iatrogenic (from prior surgery), or acquired due to filariasis. [27] When massive scrotal lymphedema infection is the cause of buried penis, it is most likely secondary to infection that causes obstruction or aplasia of the draining lymphatic system. This massive lymphedema encases the penis. The most common infections are lymphogranuloma venereum and filarial infestation with Wuchereria bancrofti, which are seen in African and Asian populations but rarely in the United States or Europe. [28]

Epidemiology

Approximately 1 in 6 men in the world are circumcised. In the United States, the estimated prevalence of circumcision in men and boys aged 14 to 59 years was 80.5%, based on data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys 2005-2010. [29] The annual incidence rate of adult circumcision in the US has been calculated at approximately 98 per 100,000 person-years. [1]

Nearly all males are born with physiologic phimosis. Data have shown that the foreskin is retractable in 90% of boys by age 3 years. Only 1% of boys have physiologic phimosis that persists until age 17 years. Thus, most healthy adult men should not have phimosis; the presence of the disorder in an adult male should raise the suspicion of balanitis (infection of the foreskin), balanoposthitis (infection of glans and foreskin), diabetes, [30] or malignancy.

Congenital buried penis is uncommon. The incidence of buried penis in adulthood is unknown, but it is highly likely that many cases go unreported.

Prognosis

Phimosis does not recur after proper circumcision. If too much penile skin is left, a repeat circumcision may be necessary for medical or cosmetic reasons. In adults, some permanent skin-color discrepancy along the suture line of the circumcision may occur. Overall, careful attention to proper surgical technique will allow for a pleasing cosmetic result.

Reported results of buried-penis repair in pediatric and adult cases have generally been good. Surgery often provides immediate excellent cosmetic results with low rates of complications. Brisson et al (2001) contend that both patients and their parents derive psychological benefits from the procedure. [31] This assertion seems to be confirmed by postoperative surveys. In addition to improved confidence, improvement in personal hygiene and voiding result from buried-penis repair in both pediatric and adult patients. Adult patients often also report improved sexual performance.

-

Phimotic foreskin. The distal foreskin is edematous, with cracked fissures. The patient was unable to retract the foreskin.

-

Dorsal-slit technique. The redundant foreskin is clamped at the 12-o'clock position for 2 minutes for hemostasis.

-

In the dorsal-slit technique, the clamped foreskin is incised sharply between the 2 hemostats.

-

The dorsal slit is being completed, and the circumscribing incision (proximal skirt) has been made.

-

Dorsal-slit technique. Redundant foreskin has been excised. The distal circumcision incision is 1 cm from the coronal sulcus.

-

Dorsal-slit technique. Proximal and distal skirts are approximated circumferentially with absorbable sutures in an interrupted fashion.

-

In the sleeve technique, the circumcision is started by making a circumscribing proximal incision. The incision is carried down to the Buck fascia.

-

In the sleeve technique, a distal incision is made 1 cm proximal to the coronal sulcus.

-

Sleeve technique. Redundant foreskin is clamped at the 12-o'clock position with 2 straight hemostats. Next, the foreskin is incised between the 2 hemostats.

-

Sleeve technique. The excess foreskin is peeled off. The shaft of the penis is displaced downward using a stack of sponges as the redundant foreskin is removed.

-

Sleeve technique. Excess foreskin has been removed completely.

-

Sleeve technique. The edges of the penile skin are approximated with absorbable sutures.

-

Sleeve technique. The circumcision is completed with excellent cosmetic result.

-

The arterial blood supply of the penis arises from the internal pudendal artery. The internal pudendal artery gives off branches to the bulbar artery, cavernosal artery, and dorsal penile artery. The bulbar artery continues on as the bulbourethral artery to supply the urethra. The cavernosal artery gives rise to the helicine arteries that are end arteries. The dorsal artery of the penis gives branches off to the circumflex arteries.

-

Dorsal view of the arterial and venous blood supply of the penis.

-

Cross-section through the body of the penis.

-

Preoperative photo of a buried penis in an adult.

-

Same patient after penile reconstruction and removal of the pannus. Note the elliptical incision and marked improvement in perceived penile length.

-

Same patient at the conclusion of the procedure. Although not seen in this picture, a Foley catheter may be left in place after the operation.

-

Concealed penis secondary to a scrotal web.

-

Repair in this patient involved releasing the scrotal web and degloving the penis. This patient was found to have deficient penile skin for reconstruction.

-

Same patient after application of a split-thickness skin graft that was harvested from the left thigh.