Practice Essentials

Lymphatic filariasis, which is colloquially known as elephantiasis, is a parasitic disease caused by the nematodes Wuchereria bancrofti (see the image below), Brugia malayi, and Brugia timori. The adult worms of the species W bancrofti have a predilection for the intrascrotal lymphatic vessels in hosts; thus, hydrocele is the most common manifestation of bancroftian filariasis. In endemic areas, filarial hydrocele is a major cause of disability and disfigurement, as well as a source of direct and indirect economic loss, social stigma, family discord, and sexual burden. [1]

The adult worms of Wuchereria bancrofti have a predilection for the intrascrotal lymphatic vessels, and lymphatic obstruction can result in a fluid collection within the tunica vaginalis of the scrotum. Hydrocele is the most common manifestation of chronic W bancrofti infection in males in endemic areas. In females, similar fluid collections can develop along the canal of Nuck. Filarial hydroceles are more difficult to excise surgically than idiopathic hydroceles, because of scarring and fibrosis.

Effective treatment for lymphatic filariasis is available, and since 2000 an international program to eliminate the disease has been in progress. Because of the recent advances in medical treatment with single-dose therapies, global elimination of lymphatic filariasis is now considered possible. To interrupt transmission, districts where lymphatic filariasis is endemic must be identified and community-wide programs must be implemented to treat the entire at-risk population. Community education programs are necessary to raise awareness in affected patients.

After more than 15 years of concerted effort, Haiti has successfully scaled up mass drug administration (MDA) to achieve 100% geographic coverage and is now carrying out World Health Organization (WHO)-recommended transmission assessment survey (TAS) to stop MDA across many areas of the country. [2]

In a study of 894 households in Nepal, the coverage of mass drug administration of DEC was 95.5%; however, compliance was only 71.6%. The researchers attributed the low compliance to concerns about adverse effects. The study recommended conducting increased public awareness campaigns to enhance trust in and compliance with the drug regimen. Along with the health workers and radio/TV that has been used traditionally, mobilization of female community health volunteers was encouraged. [3]

In 1998, the pharmaceutical company SmithKline Beecham (now Glaxo SmithKline) announced a massive donation program of albendazole (several billion doses) to support this effort. This donation was coupled with a decision by Merck & Co, Inc, to expand its ongoing ivermectin (Mectizan) donation program to include treatment of lymphatic filariasis.

Various surgical procedures have been developed to remove the edematous tissue in patients with genital elephantiasis. See Treatment and Medication.

Background

Filariasis has been a known disease for thousands of years. The first documentation of this disease was found in Egyptian papyrus prior to 5000 BC. In 1900, Sir Ronald Ross, a scientist from the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, reported that lymphatic filariasis is transmitted through mosquito bites. In 1902, Ross was awarded the Nobel Prize in medicine for his discovery that malaria is transmitted to humans through mosquito bites.

Pathophysiology

Humans are the definitive host of W bancrofti. Numerous species of mosquitoes from the genera Anopheles, Culex, Aedes, and Mansonia serve as the intermediate host. In infected humans, the adult W bancrofti worms are most commonly found in periaortic, inguinal, and intrascrotal lymphatic tissue.

The microfilariae produced by the female worms enter the bloodstream and are ingested by feeding mosquitoes. Once in the mosquito, the juvenile worms pass through 2 larval stages before development halts. Subsequent blood meals taken by the mosquitoes transmit the third-stage larvae into the human dermis. The juvenile worms then migrate to lymphatic tissue in the infected human, where maturation is completed.

While the adult female worms can continue to produce microfilariae in the human host, the adult worm burden cannot increase in the absence of the intermediate host. In endemic areas, filarial infection begins in childhood and the adult worm burden increases upon repeated exposures. Acute presentations most commonly occur in the fourth or fifth decade of life.

Death of the adult worm causes an inflammatory reaction that manifests as acute filarial lymphangitis (AFL). Granulomatous nodule formation and recurrent episodes of AFL impair lymphatic flow, predisposing the host to secondary bacterial infections, which result in fibrosis, lymphatic obstruction, and lymphedema. High-protein lymphedema causes further inflammation and tissue destruction. Once damage is sufficient to overwhelm the lymphatic system, chronic hydrocele ensues.

Research has implicated the endosymbiotic bacteria Wolbachia as a possible trigger in the immune reaction following the death of adult worms. [4, 5] Release of these obligate intracellular bacteria by the dead adult W bancrofti worm increases the host’s plasma levels of interleukin (IL)–6, IL-10, lipopolysaccharide-binding protein (LBP), and soluble tumor necrosis factor (TNF)–alpha receptors. The exact role of Wolbachia in lymphatic filariasis and the possibility of novel targets for prevention and treatment, including tetracycline antibiotics, have not been fully studied.

Lymphatic filariasis tends to aggregate in families, independent of household and environment, and studies have shown that genetic factors in the host influence susceptibility to lymphatic filariasis and chronic lymphedema from it. A genome-wide association study conducted by Grover et al identified two independent genetic variants near the genes HLA-DQB2 (rs7742085) and HLA-DQA1 (rs4959107), estimated to account for 24-42% of inherited susceptibility to lymphatic filariasis susceptibility. [6]

Etiology

Eight main species of nematodes (roundworms) can cause filariasis; however, the most common is W bancrofti (100 X 0.3 mm), followed by Brugia organisms. The nematodes can live for several years in the lymphatic vessels and lymph nodes. The female worms produce microfilariae (200-300 µm), which circulate in the blood. The microfilariae infect biting Culex pipiens mosquitoes (less commonly Anopheles, Aedes, and Mansonella species).

In the mosquitoes, the microfilariae develop into the infective filariform larvae within 1-2 weeks. When the mosquitoes subsequently bite humans, the larvae infect those hosts and migrate to the lymphatic tissues, where they develop into adult worms within a year.

Epidemiology

Frequency

United States

Bancroftian filariasis is endemic in tropical regions throughout the world. In the United States, the disease may be seen in immigrants from these regions and in military personnel returning from extended deployment to these areas.

International

The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that 882 million people in 44 countries and territories are at risk for lymphatic filariasis. As of 2018, however, 51.4 million people were infected, which represents a 74% decline since the start of the WHO’s Global Programme to Eliminate Lymphatic Filariasis in 2000. More than 90% of the infections are due to W bancrofti, and of those cases, 25 million involve hydrocele. [7]

India bears the greatest burden of this disease, with more than 550 million people at risk. Other endemic areas include the sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia, parts of Latin America, and the Pacific Islands.

Prevalence rates of lymphatic filariasis and filarial hydrocele vary. A sample of nearly 5,000 people from 37 districts in Nepal reported a lymphatic filariasis prevalence of up to 40%. [8] A similar study of migrant workers in Myanmar found a prevalence of 2.4%. In endemic countries of Asia and Africa, the prevalence of filarial hydrocele in men older than 45 years commonly exceeds 50%.

Race

No racial predilection for filarial infection has been shown.

Sex

The sexual prevalence of filarial infection varies by region, possibly because of variable exposure in cultural or employment patterns that result in contact with vector species of mosquito.

Age

All ages are susceptible to microfilarial infection. Clinical manifestation and acute presentations of lymphatic filariasis increase in prevalence with age. The prevalence of filarial hydrocele also increases with age.

Prognosis

Established filarial lymphedema is a progressive condition that tends to follow a stable course within 10-15 years of clinical presentation. No medical treatment has been proven to reverse this pathology; therefore, early diagnosis and treatment are of utmost importance.

A review of surgical reconstruction techniques of 48 patients over 10 years demonstrates excellent outcomes. [9]

-

Filarial infection causing enlarged pubic lymph nodes.

-

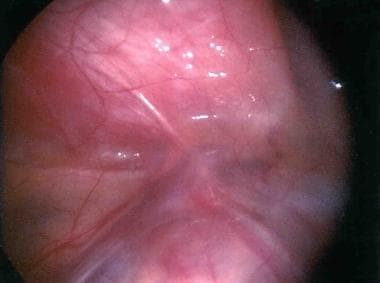

Laparoscopic view of enlarged lymphatics secondary to filarial infection.

-

Lymphocele of the right spermatic cord.

-

Microfilaria of Wuchereria bancrofti in a peripheral blood smear.

-

Unilateral left hydrocele and testicular enlargement secondary to Wuchereria bancrofti infection in a man who also was positive for microfilariae.

-

Bilateral hydrocele, testicular enlargement, and inguinal lymphadenopathy secondary to Wuchereria bancrofti infection in a man who also was microfilaremic.