Background

The origin of the name of the thymus gland is unclear. The name may have been derived from a perceived resemblance between the gland and the herb thyme; alternatively, it may have been derived from the Greek word thymos, meaning soul or heart, presumably in reference to the intimate anatomic relation between the thymus and the heart.

The first description of the thymus gland was by the Italian anatomist Giacomo da Capri (1470-1550). The Swiss physician Felix Platter reported the first case of suffocation due to hypertrophy of the thymus gland in 1614. The first indication of an association between myasthenia and the thymus gland was in 1901, when the German neurologist Hermann Oppenheim reported a tumor found growing from the thymic remnant at necropsy in a patient with myasthenia.

The report by Oppenheim led the German thoracic surgeon Ernst Sauerbruch to perform a cervical thymectomy in 1911 on a 20-year-old woman with a radiologically enlarged thymus who had myasthenia. He reported that the myasthenia was markedly improved after the surgery, but resection of thymomas in patients with myasthenia at that time was accompanied by a high mortality.

In 1936, Alfred Blalock performed a transsternal total thymectomy during a remission period from severe myasthenia. [1] By 1944, he had accumulated experience in 20 cases, firmly establishing the role of thymectomy in the treatment of these patients. [2]

Embryology

In mammals, the thymus gland develops from the ventral portion of the third branchial pouch as tubular primordia elongate caudally and fuse at the midline, losing their connection with the pharynx and leaving the definitive thymus in the mediastinum.

The thymus is the first lymphoid organ that develops. Normal peripheral lymph nodes depend on seeding by small lymphocytes from the thymus. The thymus reaches its greatest size at puberty, after which time it undergoes slow involution and both cortical and T lymphocytes are reduced in peripheral blood.

Anomalies of thymus

Cervical thymic cysts may form from persistent remnants of the tubular upper end of the primitive organ. [3] This is an extremely rare clinical condition.

Undescended thymus can be bilateral, but it is more commonly unilateral on the left side. Undescended thymus is usually diagnosed in childhood.

Accessory thymus body along the line of embryonic descent is common but is not clinically significant (it may be found in 25% of the population).

Thymic agenesis is an autosomal recessive disease often associated with agenesis of the parathyroid glands (DiGeorge syndrome), which leads to early death from infections or cardiac defects. Thymus and parathyroid transplant are the only possible treatments.

In thymic aplasia, the thymus is small. Usually, reticular cells and large lymphocytes are present without the small lymphocyte and Hassall bodies. Thymus and fetal liver implants to reconstitute T- and B-cell function have met with some success.

Anatomy

The thymus is composed of two distinct lobes, each of which is surrounded by a collagenous capsule with septa that extend into the corticomedullary junction, dividing the cortex further into lobules.

Arterial supply to the thymus varies. It could be derived from the internal mammary artery, from the inferior thyroid artery, or from these two plus the superior thyroid artery. A single vein frequently leaves each side of the medial lobe. The veins join to form a short, wide vein that drains into the left brachiocephalic vein. A lateral vein drains from the right side of the gland into the superior vena cava (SVC) and from the left side into the left brachiocephalic vein.

A hypothalamic-thymic neural pathway has been suggested to explain the numerous neurologic, social, psychological, and environmental factors that have been shown to influence the thymic hormones and the immune system.

Histology

The thymus gland contains the following three major cell populations:

-

Epithelial cells

-

Hematopoietic cells

-

Accessory cells

Epithelial cells

Epithelial cells are mainly responsible for the creation of the necessary microenvironments and their factors. They promote different steps of intrathymic T-cell differentiation and maturation. Previously, epithelial cells were referred to as pale and dark cells, with the cortex containing pale cells and the medulla containing both pale and dark cells. These cells are now categorized into the following six types, with intermediate gradation:

-

Type 1 - Subcapsular-perivascular cells

-

Type 2 - Pale epithelial cells, predominate in the outer cortex

-

Type 3 - Probably thymic nurse cells that have the unique feature of emperipolesis

-

Type 4 - Dark cells that are typical in the medulla

-

Type 5 - Undifferentiated cells that are typical in the medulla

-

Type 6 - Large medullary cells that are found around and in the Hassall corpuscles, characteristic of the medulla; may contain (in addition to epithelial cells) various cell types and have the ability to accumulate antigen

Hematopoietic cells

Three main morphologically distinct types of lymphoid cells of the adult human thymus exist,as follows:

-

Subcapsular

-

Cortical

-

Medullary

These seem to correspond to the three functional subsets of thymocytes recognized by the identification of cluster of differentiation antigens (ie, classes I, II, and III). The human thymus, especially in the fetus, supports erythropoiesis and granulopoiesis. Mast cells are formed in the thymus throughout life.

Accessory cells

Macrophages secrete a thymocyte-differentiating factor that is mitogenic and induces functional maturation of the thymocyte. Interdigitating cells have a role in determining which T-cell precursors (helper or killer) are activated during an immunologic challenge. Myoid cells demonstrate acetylcholine receptors and have a possible role in myasthenia gravis (MG). They may have a role in expelling thymocytes from the glands.

Physiology

The lymphocytes are attracted to the thymus by chemotactic factors of epithelial origin. After they colonize the epithelium, they may be bathed constantly by circulating self-antigens. These antigens enter the thymus via a transcapsular route, a step believed to be critical in the processes of learning and self-recognition.

The thymic epithelium provides the principal signals of differentiation through direct cell contact (presentation of major histocompatibility complex [MHC] antigens) and the mediation of multiple hormones, including the following:

-

Thymopoietin - This hormone depresses neuromuscular transmission, induces T-cell markers, and has a role in the generation of cytotoxic T cells and prevention of autoimmunity [4]

-

Thymulin - This hormone stimulates most T-cell functions, provided that they are not too immature, in which case they would need concomitant direct contact with the thymic epithelium

-

Thymosin alpha 1

Thymic Hyperplasia

Hyperplasia is an increase in the volume of the thymus gland deriving from the formation of new cellular elements in a normal microscopic arrangement. Two morphologic types exist: true hyperplasia and lymphofollicular hyperplasia.

True hyperplasia

True hyperplasia is characterized by an increase in both the size and the weight of the thymus. Thymic hyperplasia is a very rare pathology that presents clinically or radiologically as a mediastinal mass. It is divided into three clinicopathologic subtypes, as follows:

-

Massive thymic hyperplasia

-

Thymic rebound in childhood and adolescence

-

Other

Massive thymic hyperplasia is a rare pathologic finding, with only a few well-documented cases. Enlargement of the thymus, however, is common in infancy. The cause is unknown; it may be due to thymic hyperfunction or dysfunction related to the endocrine activity of the gland. Patients usually present with symptoms of irritation of the mediastinal structures; symptoms may range from none to respiratory distress.

Thymic rebound in childhood and adolescence is described in numerous settings (eg, during recovery from severe thermal burns, [5] after cardiac surgery, in tuberculosis, after treatment for different malignancies, and after discontinuance of oral steroids).

The functionally active thymus in childhood and adolescence may be susceptible to the fluctuation in corticosteroid levels, which is thought to be a causative factor in thymic hyperplasia (reversal of elevated endogenous corticosteroids in severe burns, withdrawal of exogenous corticosteroids in malignancy treatment).

Patient age ranges from 2 to 12 years. All reported cases were detected on routine chest radiography with no other clinical or laboratory positive finding.

After malignancy, thymic hyperplasia could be confused radiologically with recurrence or metastasis.

Finally, thymic hyperplasia has been reported in association with sarcoidosis and endocrine abnormalities (thyrotoxicosis, hypothyroidism, Addison disease, acromegaly).

Workup

Leukocytosis, lymphocytosis, and hypogammaglobulinemia were reported, but blood test results may be completely normal. Chest radiography shows widening of the mediastinum; computed tomography (CT) shows the enlarged thymus.

Management

A child with a newly recognized anterior mediastinal mass could be observed carefully if he or she is thriving and most of the alternative diagnosis possibilities have been ruled out by appropriate clinical and laboratory examinations.

A brief course of steroids could be attempted if a corticosteroid-sensitive tumor could be ruled out. Steroids often shrink a hyperplastic thymus. If the steroid test is inconclusive or if hyperplasia persists for more than 2 years, a diagnostic mediastinoscopy is necessary. In a case involving a symptomatic or calcified mass, complete resection is needed to make the diagnosis and to rule out malignancy.

Lymphofollicular thymic hyperplasia

Lymphofollicular thymic hyperplasia is characterized by its histologic appearance, which is composed of lymph follicles with germinal centers similar to those in the lymph nodes in the medulla of a normal-sized thymus. The number of these follicles varies considerably from one patient to another and within different parts of the same gland, which explains why the diagnosis may be overlooked on single section or small biopsies.

Lymphofollicular thymic hyperplasia has been categorized in the following manner:

-

Chronic disseminated infections

-

Endocrinopathies

-

Autoimmune diseases - MG, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), scleroderma, rheumatoid arthritis (RA), periarteritis nodosa, Hashimoto thyroiditis, autoimmune anemia, Behçet disease, ulcerative colitis (UC), multiple sclerosis (MS), hepatic cirrhosis

Classification of Thymic Neoplasms

The histologic classification system proposed in 1999 by the World Health Organization (WHO) recognized the following six different types of thymic tumors [6] :

-

Type A - Neoplastic spindle-shaped epithelial cells without atypia or neoplastic lymphocytes

-

Type AB - Tumors similar to type A but with a focus of neoplastic lymphocytes

-

Type B1 - Tumors that resemble normal thymic cortex with areas similar to thymic medulla

-

Type B2 - Scattered neoplastic epithelial cells with vesicular nuclei

-

Type B3 - Composed predominantly of epithelial cells that exhibit mild atypia

-

Type C - Thymic carcinoma

Previously, all of these tumors had been designated as thymomas. Subsequently, they came to be divided into two distinct categories, thymomas and thymic carcinomas. [7]

The WHO classification was revised in 2015, with the addition of an International Thymic Malignancy Interest Group (ITMIG) consensus statement aimed at refining the criteria for each subcategory. [8]

Thymomas

A thymoma is a neoplasm consisting of cytologically bland thymic epithelial cells. [9] Thymoma is the most common primary neoplasm of the mediastinum, accounting for 15% of all mediastinal masses. Patients are aged 40-60 years, with equal incidence in males and females. Thymomas present in 50% of the cases as anterior-superior mediastinal masses discovered incidentally on routine chest radiograph.

Clinical presentation

Some 25% of patients describe vague chest problems. Patients may present with symptoms of thoracic structural displacement (cough, dyspnea, palpitation, dysphagia, SVC syndrome, or substernal aching pain). In a few reported cases, thymoma presented as one of various paraneoplastic syndromes, such as MG, pure erythroid aplasia (poor prognosis), or acquired hypogammaglobulinemia. Rarely, thymoma occurs in an ectopic location (posterior mediastinum, pulmonary parenchyma, and the base of the neck). [10]

Workup

Imaging studies

Posteroanterior and lateral chest radiographs show a small, rounded mediastinal mass. Approximately 15% of thymomas show calcification, usually amorphous patches. Clearly defined tumors smaller than 5 cm in diameter are likely to be noninvasive. On the other hand, more than 50% of tumors are larger than 8 cm, flat, irregular or poorly defined, and invasive.

CT of the thorax with contrast demonstrates the extension of the thymoma to the mediastinum or pleura. Noninvasive thymomas appear as round or oval, well-circumscribed masses within the thymus. Invasive tumors appear as irregular, ill-defined masses with obliteration of the tissue planes defined by mediastinal fat. About 30% of thymomas are invasive. CT is the best nonsurgical method of detecting extension to the pleura and transpleural spread and should encompass the whole thorax to the most inferior extent of the posterior diaphragmatic sulci and the abdomen, in case of diaphragmatic involvement. [11]

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is superior to CT in its ability to image coronal and sagittal planes in addition to the axial plane. Pneumomediastinography, venography, and arteriography are rarely used in current practice. Bone scanning identifies bone metastases. Gallium-67 citrate is taken by lymphoma and may help in the differential diagnosis.

Procedures

Fine-needle aspiration (FNA) biopsy (FNAB) may allow an outpatient diagnosis for planning definite treatment or nonoperative therapy in patients who are poor candidates for anesthesia. A high success rate has been reported, with a pneumothorax rate as low as 6%. Nevertheless, in predominantly lymphocytic and spindle cell thymomas, ruling out a malignant small cell lymphoma and mesenchymal lesions may be difficult.

Mediastinoscopy can be performed on an outpatient basis. It provides larger tissue samples.

Histology

Thymomas have a well-defined fibrous capsule with internal septation. They are composed of varying proportions of neoplastic epithelial cells and lymphocytes. Mitotic activity usually is scanty, and atypical mitoses are absent. Thymomas are divided into the following three types:

-

Predominantly lymphocytic

-

Mixed lymphoepithelial

-

Predominantly epithelial (a special variant is spindle cell thymoma)

The most important factor in predicting the behavior of a thymoma is the clinical stage. The Masaoka-Koga system has been widely used and includes the following stages:

-

Stage I - Intact capsule

-

Stage II - Local invasion into the surrounding tissue

-

Stage IIa - Macroscopic invasion into surrounding fat or pleura

-

Stage IIb - Microscopic invasion into the capsule

-

Stage III - Gross invasion of the surrounding organs

-

Stage IVa - Disseminated disease, intrathoracic

-

Stage IVb - Lymphogenous or hematogenous extrathoracic metastasizing thymomas (extremely rare [< 5%]; supposedly caused by embolic spread to the cervical lymph nodes, bones, liver, and brain)

Genetics

Epidermal growth factor (EGF) receptor (EGFR) expression was found to be present in 83% of patients with thymomas and 50% of those with thymic carcinomas. C-kit was found to be positive in 73% of patients with thymic carcinomas and 5% of those with thymomas. p53 protein accumulation is present in 75% of patients with thymic carcinomas and correlates with more advanced stages and less resectability; however, mutations are infrequent.

These findings are valuable as prognostic and, potentially, preventive tools. They could also form a base for novel diagnostic and therapeutic approaches. Cases of dramatic response to imatinib in patients with metastatic thymic carcinoma and strong kit expression have already been reported. [12]

Treatment

Surgical resection is the mainstay of treatment. [13, 14, 15]

Procedural details

Thymic tumors are occasionally associated with pancytopenia, red cell hypoplasia, Cushing syndrome, Addison disease, and hypogammaglobulinemia. A proper workup should include investigation and correction of these abnormalities. Determining if the airway is compromised is important in considering the anesthetic technique. Neoadjuvant treatment before exploration should be considered if concern exists that a complete excision cannot be accomplished. [14]

For confirmed thymoma, a median sternotomy is the incision of choice. Transcervical thymectomies were reported mostly for tumors that were discovered at the time of surgery. Lateral thoracotomies are appropriate for anterior large lateralized thymomas where controlling the pulmonary hilum is necessary. In selected patients, minimally invasive thymectomy can be safe and effective. [16, 17]

Noninvasive thymomas are cured by surgical excision alone in 85-90% of cases. Invasive thymoma is diagnosed by the surgeon's assessment of evidence of invasion by the tumor into the adjacent tissues. Adherent pericardium, pleura, or lung should be resected with the thymoma. Radical exenteration of the anterior mediastinum has been strongly recommended for thymomas without MG. Special attention should be paid to avoid tumor spillage.

A systematic review and meta-analysis by Papadimas et al suggested that for nonmyasthenic patients with early-stage thymoma, partial thymectomy is oncologically equivalent to complete thymectomy, with the additional advantages of reduced postoperative complications and a shorter hospital stay. [18]

Postoperative care

Adjuvant radiation therapy (RT) remains controversial. [13, 15, 19, 20] The series that address this issue are retrospective reviews, and the role of RT in these cases remains unclear. Some recommend it for tumors larger than 5 cm or for stage II and III tumors that have been completely resected. The benefit for a patient with a stage I tumor is marginal, at best. RT appears to decrease the recurrence rate of incompletely resected tumors. [14]

Several series suggest that multimodality treatment (preoperative chemotherapy, surgery, and postoperative chemotherapy or RT) of stage III and IVa thymic tumors allows good long-term outcome; the neoadjuvant chemotherapy improves resectability and survival rates in these cases. [13, 21]

Metastasizing thymomas usually are treated solely with chemotherapy with cisplatin-based combination chemotherapy (doxorubicin, vincristine, cyclophosphamide, cisplatin). No consensus has been reached on the best approach in these cases.

Recurrent tumors are treated by reexcision, in addition to both chemotherapy and radiation therapy [22] (7-year survival rate, 70%).

Bulky unresectable masses are treated primarily with chemotherapy, surgical debulking, and radiation therapy. Some studies show improved survival (especially at 5 years) with debulking, while other authors argue that this provides no additional benefit over biopsy. [23, 15]

Follow-up

CT is recommended as a baseline test and periodically after resection to evaluate for recurrence.

Prognosis

Patients older than 60 years have a higher mortality as a result of tumor growth. Pure spindle cell neoplasms seem to act as benign tumors, rarely causing death. No neoplasms smaller than 5 cm were reported to cause recurrence or death. Patients with tumors 10 cm or larger have a higher mortality. The presence of mediastinal displacement symptoms is a poor prognostic indicator.

The 10-year survival rate for stage I thymoma is 85-100%. The 10-year survival rate for stage II thymoma is 60-84%. The reported 10-year survival rate for stage III is 21-77%. Thoracic relapses after radiation occurred in 15%. The reported 10-year survival rate for stage IV is 26-47%. Thoracic relapses after radiation occurred in 50% of patients, and 90% of these relapses were outside of the radiation field.

Thymic Carcinomas

Thymic carcinomas are cytologically malignant. They are rare tumors, and there are few specific pathologic findings to distinguish them from other histologically similar metastatic neoplasms (large cell lymphoma, seminoma, embryonal carcinoma, and sarcoma).

Clinical presentation

Most patients present with advanced disease (stage III or IV) that manifests as mediastinal masses. These masses are revealed by routine chest radiographs. They are associated more frequently with symptoms of mediastinal structural displacement and extrathoracic metastasis. MG, erythroid hypoplasia, and hypogammaglobulinemia have not been reported with thymic carcinoma.

Workup

Alpha fetoprotein (AFP) and beta human chorionic gonadotropin (β-hCG) help in distinguishing the differential diagnosis of germ cell tumors.

Chest radiography is indicated. CT or MRI in addition to positron emission tomography (PET) is indicated in all patients with a suspected mass. [11] FNAB and core needle biopsy (CNB) are indicated. Mediastinoscopy provides a large tissue sample.

Immunohistochemistry provides the most useful method to differentiate thymic carcinoma from other similar neoplasms. Thymic carcinomas are typically rubbery or gritty and gray-white with areas of hemorrhage and necrosis. Cystic changes were reported in some cases. Several distinctive microscopic variants are recognized, as follows:

-

Lymphoepitheliomalike squamous carcinoma

-

Keratinizing squamous carcinoma

-

Basaloid squamous carcinoma

-

Clear cell thymic carcinoma

-

Sarcomatoid carcinoma

-

Mucoepidermoid carcinoma

Treatment

Complete surgical resection, if technically feasible, has the best long-term result. [14] Involved structures (anterior pericardium, lung) should be resected en bloc with the tumor. Widely invasive tumors are best treated with RT, with or without cytotoxic drugs.

Prognosis

The mortality is higher than 85% in reported cases; median survival among patients with incompletely resected tumors is 12-36 months. RT and chemotherapy have offered little therapeutic benefit.

Other Thymic Tumors

Neuroendocrine tumors

Thymic carcinoid tumors are rare (150-200 cases have been reported). About 30% of thymic carcinoid tumors are associated with Cushing syndrome. Inappropriate ectopic production of antidiuretic hormone, hypertrophic osteoarthropathy, and Lambert-Eaton syndrome also has been reported.

Thymic oat cell carcinoma is very rare (20% of neuroendocrine tumors). Most apparent oat cell carcinomas are metastatic tumors from an occult bronchogenic neoplasm, which must be ruled out clinically.

Thymic germ cell tumors

These include the following:

-

Teratomas

-

Seminomas

-

Embryonal carcinomas

-

Yolk sac tumors

-

Teratocarcinomas

-

Choriocarcinomas

Thymic lymphomas

Hodgkin lymphoma is more common; the nodular sclerosing type is the most common variant. Non-Hodgkin lymphoma has also been observed.

Myasthenia Gravis

MG is an autoimmune disorder of neuromuscular transmission in which antibodies reduce the number of acetylcholine receptors at the neuromuscular junction. The condition was first recognized by Wilks in 1877, and the term myasthenia gravis pseudoparalytica was used first by Jolly a few years after. No effective therapy existed until 1934, when Walker used physostigmine, followed by Blalock's introduction of surgical therapy. [24]

Classification

MG develops in both adults and children. Pediatric MG may be subclassified as follows:

-

Neonatal (1%) - Self-limited and due to placental transfer of antibodies from the myasthenic mother

-

Juvenile (9%) - Permanent

Adult MG may be subclassified as follows:

Ocular (20%)

-

Mild generalized (30%)

-

Moderate generalized (20%)

-

Acute fulminating (11%) - Prominent respiratory symptoms

-

Late severe (9%) - Progress after 2 years of mild disease

Epidemiology

The incidence of MG is 0.5-5 cases per 100,000 population, and the prevalence has been on the rise for the past several decades. All ages are at risk. The peak age at onset is 20-30 years in women and older than 50 years in men. The female-to-male ratio is 3:2 in the general population and 5:1 in young patients.

Pathophysiology and etiology

The pathophysiology involves antibody-mediated destruction of the acetylcholine receptors by induction of cross-linking of the receptors, resulting in accelerated endocytosis and subsequent degradation of the receptors, with a possible role for complement-mediated end-plate destruction and simple binding and blockage of the receptors by the antibodies.

Although the source of autoantibodies in MG is unknown, the thymus is thought to have a major role in the pathology of this disease. The thymic myoid cells, with their resemblance to embryonic muscle cells, serve as the antigen source for the development of these antibodies.

The role of the thymus is suspected on the basis of the following:

-

The thymus gland is abnormal in 80% of patients (60% have follicular lymphoid hyperplasia, 10-20% have thymoma)

-

About 30-60% of patients with thymoma have (or subsequently develop) MG

-

Acetylcholine receptor antibodies and antibodies to striated muscle have been demonstrated in the thymus of patients with MG

-

Thymectomy has a proven beneficial therapeutic role for these patients

Clinical presentation

Weakness or fatigability occurs with repetitive exercise and resolves with rest. The clinical course is unpredictable and characterized by frequent spontaneous remission and relapses.

The muscle groups involved and the degree of their involvement vary considerably over time. Ocular muscles are the most frequently involved, resulting in ptosis and diplopia, which can be exaggerated by a sustained upward gaze. Proximal muscle groups are involved more frequently than the distal groups. Deep tendon reflexes are preserved.

Workup

No single test result is uniformly positive, but combination of these tests with the clinical picture establishes the diagnosis in most patients.

Elevated acetylcholine receptor antibody titers are highly specific for MG. The sensitivity ranges from 64% in patients with only ocular symptoms to 89% in patients with generalized disease.

Imaging studies that may be helpful include chest radiography and CT to exclude the presence of thymoma.

The results of single-fiber electromyography (EMG) have been shown to be positive in 60-75% of patients with ocular MG, in 90% of patients with mild generalized MG, and in 100% of those with moderate-to-severe disease.

Short-acting cholinesterase medications, such as edrophonium, could be used as a diagnostic test for MG. When administered intravenously (IV), they produce significant improvement in muscle strength, usually within 30-60 seconds. The sensitivity of this test is approximately 85% for ocular MG and 95% for generalized disease.

Differential diagnosis

Conditions to be considered in the differential diagnosis include the following:

-

Muscular atrophy

-

Psychoneurosis

-

Organophosphate intoxification, snakebites, and drug-induced (penicillamine, procainamide, and aminoglycoside) myasthenia

-

Eaton-Lambert syndrome (associated with malignancy)

Medical therapy

Pharmacologic therapy

Only a few drugs are available for pharmacologic treatment of MG. Cholinesterase inhibitors decrease hydrolysis of acetylcholine, thereby increasing the amount of acetylcholine available in the synaptic cleft and providing symptomatic relief. They have no effect on the course of MG.

Optimal dosage varies widely; dosing should be adjusted on a personal basis by using the minimal dose necessary to achieve an effect while avoiding muscarinic adverse effects (abdominal cramping, diarrhea, excessive salivation, diaphoresis, and bradycardia). A feared adverse effect is cholinergic crisis, which produces a depolarizing-type neuromuscular blockade that could be confused clinically with myasthenic crisis.

Specific agents include the following:

-

Pyridostigmine - Long-duration action (adverse effects may include nausea/vomiting, sweating, diarrhea, weakness, muscle cramps, psychosis, miosis)

-

Neostigmine - More rapid onset and shorter duration of action (insensitivity to this drug may develop)

-

Edrophonium - Very rapid onset and short duration of action; used for diagnostic purposes

Corticosteroids are usually reserved for patients who fail to respond to or do not tolerate anticholinesterase therapy. They also have been used to prepare patients for thymectomy. They provide symptomatic improvement in as many as 80% of the patients, but relapse is common after discontinuance. The risk associated with long-term steroid use is always a matter of concern.

Immunosuppression with azathioprine is used for patients who do not respond to or do not tolerate anticholinesterase therapy. The response rate is 70-80%. Adverse effects are common.

IV immunoglobulin (IVIg) 1 g/kg has been shown to be effective in the treatment of exacerbations of MG; however, other studies did not find this approach to be superior to plasmapheresis [25] (see below) or oral steroid therapy. Similarly, there has been insufficient evidence to suggest that IVIg is efficacious in the treatment of chronic MG. [26]

Plasma exchange

Antibody removal by plasmapheresis produces symptomatic relief in as many as 90% of patients. It is extremely effective when dramatic and rapid response is necessary, with a response rate superior to that of IVIg. [25] Five exchanges are required. The effects last a few weeks; thus, the use of plasmapheresis is limited to the short term, such as during myasthenic crisis and in the perioperative period.

Radiation therapy

Total-body irradiation has been used successfully in thymectomized patients who were refractory to other treatments, with clinical improvement lasting more than 2 years in 40% of the reported cases. [27]

Surgical therapy

The benefit of thymectomy is based on observation. [28] The mechanism is still unknown, as is which patients are more likely to respond. A prospective randomized international trial to assess the role of thymectomy in MG is under way. [29]

Patients are usually considered for thymectomy when they do not respond to treatment with cholinesterase inhibitors or when the adverse effects limit the benefit of this treatment.

Observation suggests that patients with short duration of symptoms are most likely to benefit from the operation, which is the rationale for early consideration of patients with generalized symptoms for surgery. [30]

Some studies report similar results with patients with isolated ocular symptoms. In these patients, thymectomy prevented the progression to generalized disease. Given the low morbidity of the transcervical approach, some surgeons recommend transcervical thymectomy for these patients.

If thymoma is present, surgery should be performed as soon as symptoms can be controlled.

Procedural details

Symptoms must be controlled medically before surgery, with special attention to optimizing the respiratory mechanics. Paralyzing agents should be used with caution for anesthesia. They have a rapid onset and more marked neuromuscular block, which decreases their safety margin. In addition, the rate of recovery from the block is not enhanced by neostigmine.

Transcervical thymectomy carries low morbidity, with remission and response rates that are comparable with those of transsternal thymectomy. Transsternal thymectomy ensures the removal of all the adjacent cervical and mediastinal fat, which may contain aberrant thymic tissue.

Complete thoracoscopic thymectomy has been shown to be feasible with comparable midterm results and less morbidity. [31, 32, 33] No prospective randomized study is available to compare it with the transsternal and transcervical approaches.

As an ideal technology for dissection in a small anatomic area, robotic thymectomy [34] has the potential to offer minimally invasive surgery with the same result as from the more invasive "maximal thymectomy" approach. [35] Additional advantages include minimizing pain and improving cosmesis. Five groups reported short-term results, totaling 200 cases. Operating time was 2-5.2 hours, morbidity was 2-10%, median hospital stay was 2-5 days, and no mortality was reported. Long-term outcomes have yet to be demonstrated. [36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41] Complications may be fewer with a left-side as opposed to a right-side approach. [42]

An analysis utilizing data from the Society of Thoracic Surgeons General Thoracic Surgery Database assessed perioperative complications of open and minimally invasive thymectomy techniques in MG patients and found that minimally invasive (video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery [VATS] and robotic VATS) and transcervical thymectomies were associated with fewer perioperative complications than transthoracic thymectomies when performed for nonthymomatous MG. [43]

Postoperative care

Aggressive pulmonary care is provided. Anticholinesterase medication (the same as is used preoperatively) is continued after extubation. The benefit of the procedure may not be apparent for years. Mild cases may be exacerbated after thymectomy. Reoperation should be considered if incomplete resection is suspected.

Prognosis

A few decades ago, 25% of patients with MG died of the condition. Current treatments provide a normal life expectancy for patients.

Age younger than 45 years, hyperplastic gland, and female sex have been reported as predictors of improvement after thymectomy. The presence of thymoma is associated with higher likelihood of more severe symptoms and with less improvement after thymectomy. The complete remission rate after thymectomy is 33% in general and 17% in patients with isolated ocular symptoms, compared with 8% after medical treatment, with a survival advantage after thymectomy. Symptomatic improvement was reported in 80-94% of patients after thymectomy. A small percentage of patients fare worse after thymectomy or have recurrence after improvement.

The Myasthenia Gravis Foundation of America standardized the description of surgical approach into the following:

-

T-1 Transcervical (a) basic (b) extended

-

T-2 Videoscopic (a) classic (b) video-assisted thorascopic extended thymectomy (VATET)

-

T-3 Transsternal (a) standard (b) extended

-

T-4 Transsternal and transcervical

Evidence supports superior results with T-3b (50%) and T-4 (81%) techniques compared to T-1a (32%). In one study, all 15 reoperations after T-1a and T-3a revealed residual thymus, with symptomatic improvement after complete resection in 13 of these patients. [44, 45]

-

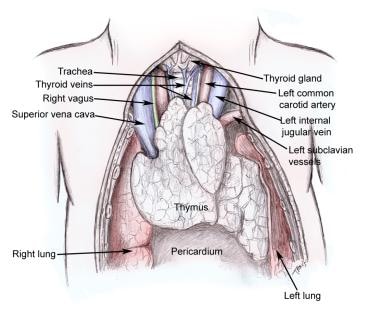

Thymus gland and surrounding structures.