Practice Essentials

Pericardial effusion is the presence of an abnormal amount of fluid and/or an abnormal character to fluid in the pericardial space. It can be caused by a variety of local and systemic disorders, or it may be idiopathic. See the image below.

Signs and symptoms

Signs and symptoms of pericardial effusion include the following:

-

Chest pain, pressure, discomfort

-

Light-headedness, syncope

-

Palpitations

-

Cough

-

Dyspnea

-

Hoarseness

-

Anxiety and confusion

-

Hiccoughs

See Clinical Presentation for more detail.

Diagnosis

Examination findings in patients with pericardial effusion include the following:

-

Classic Beck triad of pericardial tamponade: Hypotension, muffled heart sounds, jugular venous distention

-

Pulsus paradoxus

-

Pericardial friction rub

-

Tachycardia

-

Hepatojugular reflux

-

Tachypnea

-

Decreased breath sounds

-

Ewart sign: Dullness to percussion beneath the angle of left scapula

-

Hepatosplenomegaly

-

Weakened peripheral pulses, edema, and cyanosis

Lab tests

The following laboratory studies may be performed in patients with suspected pericardial effusion:

-

Electrolyte levels

-

CBC count with differential

-

Cardiac biomarker levels (eg, troponin, CK-MB, LDH)

-

Tests for other markers of inflammation (eg, ESR, CRP)

-

TSH level

-

Blood cultures

-

RF levels

-

Immunoglobulin complex tests

-

ANA tests

-

Complement levels

-

Pericardial fluid analysis

Early in the course of acute pericarditis, the ECG typically displays diffuse ST elevation in association with PR depression; the ST elevation may be present in all leads except for aVR, although in postmyocardial infarction pericarditis, the changes may be more localized.

Specific tests for infectious diseases or other conditions may also be warranted, based upon clinical suspicion, such as the following:

-

Viral cultures

-

Tuberculin skin testing or QuantiFERON-TB assay

-

Rickettsial antibodies

-

HIV serology

-

Adenosine deaminase levels

-

CEA levels

-

PCR

Imaging studies

Echocardiography is the imaging modality of choice for the diagnosis of pericardial effusion and includes the following techniques:

-

2-D echocardiography

-

M-mode echocardiography: Adjunct to 2-D echocardiography

-

Doppler echocardiography

-

Transesophageal echocardiography

-

Intracardiac echocardiography

Other radiologic studies used in the evaluation of pericardial effusion include the following:

-

Chest radiography

-

Chest CT Scanning and MRI: May be superior to echocardiography in detecting loculated pericardial effusions

Procedures

Procedures that may be used in patients with pericardial effusion include the following:

-

Diagnostic and/or therapeutic pericardiocentesis

-

Diagnostic pericardioscopy

-

Placement of a pulmonary artery catheter

See Workup for more detail.

Management

Most acute idiopathic or viral pericarditis occurrences are self-limited and respond to treatment with an NSAID. Colchicine or prednisone may be administered for severe inflammatory pericardial effusions or when NSAID treatment has failed. Colchicine is preferred over steroids (unless specifically indicated), as the latter is associated with an increassed incidence of recurrent pericarditis.

Autoimmune pericardial effusions may respond to treatment with anti-inflammatory medications. In general, selection of an agent depends on the severity of the patient's symptoms and the tolerability and adverse-effect profiles of the medications.

Pharmacotherapy for pericardial effusion includes use of the following agents, depending on the etiology:

-

NSAIDs (eg, indomethacin, ibuprofen, naproxen, diclofenac, ketoprofen, aspirin)

-

Corticosteroids (eg, prednisone, methylprednisolone, prednisolone)

-

Anti-inflammatory agents (eg, colchicine)

-

Antibiotics (eg, vancomycin, ceftriaxone, ciprofloxacin, isoniazid, rifampin, pyrazinamide, ethambutol)

-

Antineoplastic therapy (eg, systemic chemotherapy, radiation)

-

Sclerosing agents (eg, tetracycline, doxycycline, cisplatin, 5-fluorouracil)

Hemodynamic support for pericardial effusion includes the following:

-

Hemodynamic monitoring with a balloon flotation pulmonary artery catheter

-

IV fluid resuscitation

Surgical treatments for pericardial effusion include the following:

-

Pericardiostomy

-

Pericardotomy

-

Thoracotomy

-

Sternotomy

-

Pericardiocentesis

See Treatment and Medication for more detail.

Background

Pericardial effusion is the presence of an abnormal amount of and/or an abnormal character to fluid in the pericardial space. It can be caused by a variety of local and systemic disorders, or it may be idiopathic. (See Etiology.)

Pericardial effusions can be acute or chronic, and the time course of development has a great impact on the patient's symptoms. Treatment varies, and is directed at removal of the pericardial fluid and alleviation of the underlying cause, which usually is determined by a combination of fluid analysis and correlation with comorbid illnesses (see the image below). (See Presentation, Workup, Treatment, and Medication.)

This image is from a patient with malignant pericardial effusion. Note the "water-bottle" appearance of the cardiac silhouette in the anteroposterior (AP) chest film.

This image is from a patient with malignant pericardial effusion. Note the "water-bottle" appearance of the cardiac silhouette in the anteroposterior (AP) chest film.

Embryology

In the human embryo, the pericardial cavity develops from the intraembryonic celom during the fourth week. The pericardial cavity initially communicates with the pleural and peritoneal cavities, but during normal development these are separated by the eighth week.

The visceral and parietal pericardium are derived from the mesoderm, albeit from different parts of the embryo. The visceral pericardium develops from splanchnic mesoderm, as cells originating from the sinus venous spread out over the myocardium. The parietal pericardium derives from lateral mesoderm that covers and accompanies the developing pleuropericardial membrane, which will eventually separate the pleural and pericardial cavities. In healthy subjects, the pericardium covers the heart and great vessels, with the exception of only partially covering the left atrium.

Congenital absence of the pericardium can occur and can be either partial or complete. This condition is often clinically silent, but it can potentially lead to excessive cardiac motion (in the case of complete absence), causing vague chest pain or dyspnea, or, in the case of partial absence with significant defects, strangulation of heart muscle and possible death. [1]

Physiology

The pericardial space normally contains 15-50 mL of fluid, which serves as lubrication for the visceral and parietal layers of the pericardium. This fluid is thought to originate from the visceral pericardium and is essentially an ultrafiltrate of plasma. Total protein levels are generally low; however, the concentration of albumin is increased in pericardial fluid owing to its low molecular weight.

The pericardium and pericardial fluid provide important contributions to cardiac function, including the following:

-

The parietal pericardium contributes to resting diastolic pressure, and is responsible for most of this pressure in the right atrium and ventricle

-

Through their ability to evenly distribute force across the heart, the pericardial structures assist in ensuring uniform contraction of the myocardium

The normal pericardium can stretch to accommodate a small amount of fluid without a significant change in intrapericardial pressure, although once this pericardial reserve volume is surpassed, the pressure-volume curve becomes steep. With slow increases in volume, however, pericardial compliance can increase to lessen the increase in intrapericardial pressure.

Pathophysiology

Clinical manifestations of pericardial effusion are highly dependent on the rate of accumulation of fluid in the pericardial sac. Rapid accumulation of pericardial fluid may cause elevated intrapericardial pressures with as little as 80 mL of fluid, while slowly progressing effusions can grow to 2 L without symptoms.

Understanding the properties of the pericardium can help to predict changes within the heart under physiologic stress.

By distributing forces across the heart, the pericardium plays a significant role in the physiologic concept of ventricular interdependence, whereby changes in pressure, volume, and function in one ventricle influence the function of the other.

The pericardium plays a pivotal role in cardiac changes during inspiration. Normally, as the right atrium and ventricle fill during inspiration, the pericardium limits the ability of the left-sided chambers to dilate. This contributes to the bowing of the atrial and ventricular septums to the left, which reduces left ventricular (LV) filling volumes and leads to a drop in cardiac output. As intrapericardial pressures rise, as occurs in the development of a pericardial effusion, this effect becomes pronounced, which can lead to a clinically significant fall in stroke volume and eventually progress to the development of pericardial tamponade.

The pericardium plays a beneficial role during hypervolemic states by limiting acute cardiac cavitary dilatation.

Etiology

The cause of abnormal fluid production depends on the underlying etiology, but it is usually secondary to injury or insult to the pericardium (ie, pericarditis). Transudative fluids result from obstruction of fluid drainage, which occurs through lymphatic channels. Exudative fluids occur secondary to inflammatory, infectious, malignant, or autoimmune processes within the pericardium.

In up to 60% of cases, pericardial effusion is related to a known or suspected underlying process. Therefore, the diagnostic approach should give strong consideration to coexisting medical conditions.

Idiopathic

In many cases, the underlying cause is not identified. However, this often relates to the lack of extensive diagnostic evaluation.

Infectious

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection can lead to pericardial effusion through several mechanisms, including the following:

-

Secondary bacterial infection

-

Opportunistic infection

-

Malignancy (Kaposi sarcoma, lymphoma)

-

"Capillary leak" syndrome, which is associated with effusions in other body cavities

The most common cause of infectious pericarditis and myocarditis is viral. Common etiologic organisms include coxsackievirus A and B, and hepatitis viruses. Other forms of infectious pericarditis include the following:

-

Pyogenic - Pneumococci, streptococci, staphylococci, Neisseria, Legionella species

-

Tuberculous

-

Fungal - Histoplasmosis, coccidioidomycosis, Candida

-

Syphilitic

-

Protozoal

-

Parasitic

Neoplastic

Neoplastic disease can involve the pericardium through the following mechanisms:

-

Direct extension from mediastinal structures or the cardiac chamber

-

Retrograde extension from the lymphatic system

-

Hematologic seeding

Malignancies with the highest prevalence of pericardial effusion include lung (37% of malignant effusions) and breast (22%) malignancies, as well as leukemia/lymphoma (17%). However, patients with malignant melanoma or mesothelioma also have a high prevalence of associated pericardial effusions.

Postoperative/postprocedural

Pericardial effusions are common after cardiac surgery. In 122 consecutive patients studied serially before and after cardiac surgery, effusions were present in 103 patients; most appeared by postoperative day 2, reached their maximum size by postoperative day 10, and usually resolved without sequelae within the first postoperative month.

In a retrospective survey of more than 4,500 postoperative patients, only 48 were found to have moderate or large effusions by echocardiography; of those, 36 met diagnostic criteria for tamponade. The use of preoperative anticoagulants, valve surgery, and female sex were associated with a higher prevalence of tamponade. [2]

Early chest tube removal following cardiac surgery, around midnight on the day of surgery, may be associated with an increased risk of postoperative pleural and/or pericardial effusions requiring invasive treatment. [88] This may occur even if chest tube output during the last 4 hours is below 150 mL compared with removal of the tubes next morning.

Symptoms and physical findings of significant postoperative pericardial effusions are frequently nonspecific, and echocardiographic detection and echo-guided pericardiocentesis, when necessary, are safe and effective; prolonged catheter drainage reduces the recurrence rate. [3]

Pericardial effusions in cardiac transplant patients are associated with an increased prevalence of acute rejection. [4]

Other

Less common causes of pericardial effusion include the following:

-

Uremia

-

Myxedema

-

Severe pulmonary hypertension

-

Radiation therapy

-

Acute myocardial infarction - Including the complication of free wall rupture

-

Aortic dissection - Leading to hemorrhagic effusion from leakage into the pericardial sac

-

Trauma

-

Hyperlipidemia

-

Chylopericardium

-

Familial Mediterranean fever

-

Whipple disease

-

Hypersensitivity or autoimmune related -Systemic lupus erythematosus, [5] rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, rheumatic fever, scleroderma, sarcoidosis, Wegener granulomatosis

-

Drug associated - Eg, procainamide, hydralazine, isoniazid, minoxidil, phenytoin, anticoagulants, methysergide

Epidemiology

Occurrence in the United States

Few large studies have characterized the epidemiology of pericardial effusion; however, the available data consistently show that pericardial effusion is more prevalent than is clinically evident. A higher incidence of it is associated with certain diseases.

Small pericardial effusions are often asymptomatic, and pericardial effusion has been found in 3.4% of subjects in general autopsy studies. When associated with community-acquired pneumonia (CAP), small pericardial effusion is an independent predictor of adverse events including longer and more complicated hospital stays as well as increased mortality. [6]

A wide variety of malignant neoplasms and hematologic malignancies can lead to pericardial effusion. Data on the prevalence varies, with some studies showing the presence of pericardial effusion as high as 21% in such patients. A large study by Bussani et al showed cardiac metastases (9.1%) and pericardial metastases (6.3%) in cases of death from all causes in individuals with an underlying carcinoma at autopsy. [7] As previously mentioned, malignancies with the highest prevalence of pericardial effusion include lung (37% of malignant effusions) and breast (22%) malignancies, as well as leukemia/lymphoma (17%).

Patients with HIV, with or without acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), are also found to have an increased prevalence of pericardial effusion. [8] Studies have shown the prevalence of pericardial effusion in these patients to range from 5-43%, depending on the inclusion criteria, with 13% having moderate to severe effusion. The incidence of pericardial effusion in patients infected with HIV has been estimated at 11%; however, it appears that highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) may have reduced the incidence of HIV-associated effusions. [9]

Race- and age-related demographics

No consistent difference among races is reported in the literature. AIDS patients with pericardial effusion are more likely to be white.

Pericardial effusion is observed in all age groups. The mean occurrence is in the fourth or fifth decades, although it is earlier than this in patients with HIV. [8]

Prognosis

Most patients with acute pericarditis recover without sequelae. Predictors of a worse outcome include the following:

-

Fever greater than 38°C

-

Symptoms developing over several weeks in association with immunosuppressed state

-

Traumatic pericarditis

-

Pericarditis in a patient receiving oral anticoagulants

-

A large pericardial effusion (>20 mm echo-free space or evidence of tamponade)

-

Failure to respond to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

In a series of 300 patients with acute pericarditis, 254 (85%) did not have any of the high-risk characteristics and had no serious complications. Of these low-risk patients, 221 (87%) were managed as outpatients and the other 13% were hospitalized when they did not respond to aspirin.

Patients with symptomatic pericardial effusions from HIV/AIDS or cancer have high short-term mortality rates.

Morbidity and mortality

The morbidity and mortality of pericardial effusion is dependent on etiology and comorbid conditions. Idiopathic effusions are well tolerated in most patients. As many as 50% of patients with large, chronic effusions (effusions lasting longer than 6 months) have been found to be asymptomatic during long-term follow-up.

Pericardial effusion is the primary or contributory cause of death in 86% of cancer patients with symptomatic effusions. The survival rate for patients with HIV and symptomatic pericardial effusion is 36% at 6 months and 19% at 1 year.

Pericardial tamponade

Pericardial tamponade, which is heralded by the equalization of diastolic filling pressures, can lead to severe hemodynamic compromise and death. It is treated with expansion of intravascular volume (small amounts of crystalloids or colloids may lead to improvement, especially in hypovolemic patients) and urgent pericardial drainage. Positive-pressure ventilation should be avoided, if possible, as this decreases venous return and cardiac output. Vasopressor agents are of little clinical benefit.

-

This image is from a patient with malignant pericardial effusion. Note the "water-bottle" appearance of the cardiac silhouette in the anteroposterior (AP) chest film.

-

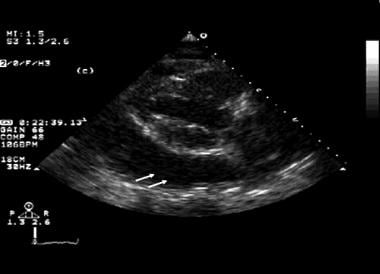

Echocardiogram (parasternal, long axis) of a patient with a moderate pericardial effusion.

-

This image is from a patient with malignant pericardial effusion. The effusion is seen as an echo-free region to the right of the left ventricle (LV).

-

This electrocardiogram (ECG) is from a patient with malignant pericardial effusion. The ECG shows diffuse low voltage, with a suggestion of electrical alternans in the precordial leads.

-

Subcostal view of an echocardiogram that shows a moderate to large amount of pericardial effusion.

-

This echocardiogram shows a large amount of pericardial effusion (identified by the white arrows).