Practice Essentials

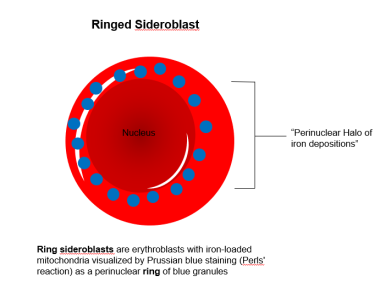

The sideroblastic anemias (SAs) are a group of inherited and acquired bone marrow disorders characterized by pathological iron accumulation in the mitochondria of red blood cell precursors (nucleated erythroblasts). [1, 2, 3] In affected erythroblasts, abnormal, iron-laden mitochondria appear to encircle the nucleus, giving rise to the defining morphologic feature of sideroblastic anemias, the ring sideroblast (RS). [4]

RSs can be detected in the bone marrow in a variety of clonal hematological and non-clonal disorders. Clonal conditions associated with the presence of RSs include myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS), myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPN) and MDS/MPN overlap syndromes. [5] Non-clonal conditions associated with the presence of RSs include alcoholism, lead poisoning, zinc overdose, copper or pyridoxine deficiency, and congenital sideroblastic anemias (CSAs). CSAs involve mutations in 1 of 3 mitochondrial pathways: heme synthesis, iron-sulfur cluster biogenesis, and protein synthesis.

Sideroblastic anemia is primarily a laboratory diagnosis, made on the basis of bone marrow examination with Prussian blue stain. The history and physical examination can provide certain clues, but they usually do not pin down the exact diagnosis. The workup may include a complete blood count (CBC), peripheral smear, iron studies (eg, ferritin and total iron-binding capacity [TIBC]), bone marrow aspiration and biopsy, and other studies as appropriate (see Workup).

Treatment of sideroblastic anemia may include the following:

-

Removal of toxic agents

-

Administration of pyridoxine, thiamine, or folic acid

-

Transfusion (along with antidotes if iron overload develops from transfusion)

-

Other medical measures

-

Bone marrow or liver transplantation

See Treatment.

Background

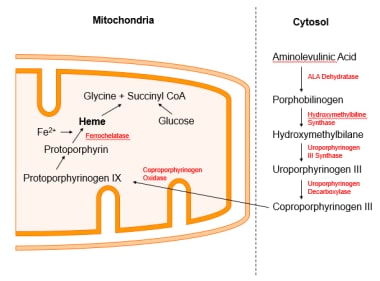

Adult human bone marrow synthesizes 4 × 1014 molecules of hemoglobin every second. [6] Heme and globin chains (alpha and beta) in adults are manufactured in separate cell compartments — mitochondria and cytoplasm, respectively — and then combined in cytoplasm in an amazingly accurate manner. Four major problems can manifest during this delicate process:

-

Qualitative defects of globin chain synthesis result in hemoglobinopathies such as sickle cell disease.

-

Quantitative defects of globin chain synthesis result in hemoglobinopathies such as thalassemia.

-

Defects in synthesis of the heme portion result in porphyrias.

-

Defects involving incorporation of iron into the heme molecule result in sideroblastic anemia.

In some instances, both the synthesis of heme and the incorporation of iron can be altered, and the result is a porphyria with sideroblasts (eg, erythropoietic protoporphyria). [7, 8]

Pathophysiology

Sideroblasts are not pathognomonic of any one disease but rather are a bone marrow manifestation of several diverse disorders. On a marrow stained with Prussian blue, a sideroblast is an erythroblast that has stainable deposits of iron in the cytoplasm. When abundant, these deposits form a ring around the nucleus, and the cells become ring sideroblasts (see the image below).

Under normal circumstances, this iron would have been used to make heme. The process occurs only in the bone marrow, because mature erythrocytes lack mitochondria, the nexus of heme synthesis (see the image below).

Congenital sideroblastic anemias

Congenital sideroblastic anemias generally involve lower hemoglobin levels, more microcytosis, and higher serum iron levels compared with myelodysplastic syndrome. [9]

Of the congenital sideroblastic anemias, X-linked sideroblastic anemias are further divided into pyridoxine-responsive (> 50%) and pyridoxine-resistant subtypes.

In the pyridoxine-responsive subtype, point mutations on the X chromosome have been identified that result in a δ-amino levulinic acid synthase (ALAS-2) with very low enzymatic activity. [10] This development impairs the first crucial step in the heme synthesis pathway, the formation of δ-amino levulinic acid, resulting in anemia despite intact iron delivery to the mitochondrion and with a lack of heme in which iron is to be incorporated in the final step of this pathway. This is the most common of the hereditary sideroblastic anemias, followed by mitochondrial transporter defects such as SLC25A38 gene mutation discussed below. [11]

A prototype of pyridoxine-resistant X-linked sideroblastic anemia is the ABC7 gene mutation. [12, 13] ABC-7 is an adenosine triphosphate (ATP)-dependent transporter protein involved in the cytosolic transfer of iron-sulfur complexes. In contrast to pyridoxine-responsive sideroblastic anemia, the ABC7 defect has a nonprogressive cerebellar ataxia component with diminished deep-tendon reflexes, incoordination, and elevated free erythrocyte protoporphyrin. [14]

Autosomal recessive sideroblastic anemia has been described in conjunction with mitochondrial myopathy and lactic acidosis in Jews of Persian descent, resulting from pseudouridine synthase-1 (PUS1) mutations. [15] Pseudouridine is a nucleoside isomer of uridine that is used as a building block in mitochondrial RNA. The defect results in impaired oxidative phosphorylation, which explains the muscle and nerve manifestations, and sideroblastic anemia due to dysfunctional mitochondria, the center of heme synthesis.

An autosomal dominantly inherited form also exists but is extremely rare. [16]

Pearson (marrow-pancreas) syndrome, described in 1979, [17] is a juvenile multisystem disorder caused by deletions in mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) and manifested as severe, refractory sideroblastic anemia, neutropenia, vacuolated cells in bone-marrow precursors, exocrine pancreas insufficiency, malabsorption, and growth failure. [18]

Nonclonal acquired sideroblastic anemias

Copper deficiency, which can occur as a part of malabsorption, [19] nephrotic syndrome (loss of ceruloplasmin), [20] gastric surgery, [21] or as a consequence of excessive zinc intake (supplements), [22] can masquerade as myelodysplastic syndrome with sideroblastic anemia and leukopenia. [23] . Low serum copper and ceruloplasmin are typical. Copper replacement reverses the hematologic abnormalities. [24]

Vitamin B6 (pyridoxine) forms pyridoxal phosphate, which acts as a coenzyme in the first, rate-limiting step in heme formation catalyzed by δ-ALAS. [25] Deficiency of vitamin B6 causes sideroblastic anemia.

Lead poisoning has been known to cause sideroblastic anemia by inhibiting several enzymes involved in heme synthesis, including δ-aminolevulinate dehydratase, coproporphyrin oxidase, and ferrochelatase. [26]

Excessive alcohol consumption can cause several forms of anemia through nutritional deficiencies (eg, of iron or folate), hemolysis, splenic sequestration due to liver cirrhosis, direct bone marrow toxicity to erythroid precursors, [27] inhibition of pyridoxine, [28] lead contamination of wine, [29] and inhibition of ferrochelatase enzyme during heme formation. [30]

Drugs reported to cause sideroblastic anemia include diverse classes, such as the following:

-

Hormones (eg, progesterone [36] )

-

Pain medicines (eg, phenacetin [37] )

-

Chemotherapy agents (eg, busulfan, melphalan) [40]

In most cases of drug-induced sideroblastic anemia, stopping the drug reverses the sideroblastic changes.

Hypothermia has been reported to cause sideroblastic anemia with a marked reduction in normoblastic erythropoiesis and thrombocytopenia with normal megakaryocytes. The changes reverse in most cases with the normalization of temperature. [41]

Clonal acquired sideroblastic anemias

In the 2016 revised World Health Organization (WHO) classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia, two myeloid neoplasms synonymous with the presence of bone marrow RS were reclassified. Refractory anemia with ring sideroblasts (RARS) was classified under myelodysplastic syndrome with ring sideroblasts (MDS-RS) and RARS with thrombocytosis (RARS-T) was renamed MDS/MPN with RS and thrombocytosis (MDS/MPN-RS-T). [42]

MDS/MPN-RS-T is also frequently associated with mutations in the spliceosome gene SF3B1 and is often co-mutated with JAK2 V617F, or less frequently (< 10%) with CALR or MPL genes. [43] In the 2022 update of the WHO classification, MDS/MPN-RS-T is renamed MDS/MPN with SF3B1 mutation and thrombocytosis; however, the term MDS/MPN-RS-T was retained for cases with wild-type SF3B1 and ≥15% ring sideroblasts. [44]

Mutation of SF3B1 appears to be an early event in MDS pathogenesis, manifests a distinct gene expression profile, and correlates with a favorable prognosis. Contrary to its poor prognostic significance in chronic lymphocytic leukemia, in MDS this mutation appears to reduce transformation into acute leukemia. [45] This mutation is not found in congenital sideroblastic anemias. [9] Studies have shown that in cases of MDS with any ring sideroblasts, the actual percentage of ring sideroblasts is not prognostically relevant. [46]

MDS-RS cases will be subdivided into cases with single lineage dysplasia (MDS-RS SLD), which was previously classified as refractory anemia with ring sideroblasts; and cases with multilineage dysplasia (MDS-RS MLD), which were previously classified as refractory cytopenia with multilineage dysplasia. [5]

Etiology

Non-clonal sideroblastic anemia

The most common form of congenital sideroblastic anemia (CSA) is caused by mutation of erythroid-specific 5-aminolevulinate synthase (ALAS2), the first enzyme of heme synthesis in erythroid cells. [9] Other CSAs include SLC25A38-related sideroblastic anemia, [47] glutaredoxin 5 (GLRX5)–related sideroblastic anemia, [48] and X-linked sideroblastic anemia with ataxia–ABCB7 mutations.

The syndromic CSA phenotypes include the following:

-

Mitochondrial myopathy with lactic acidosis and sideroblastic anemia (MLASA) caused by PUS1 mutation [49]

-

Sideroblastic anemia, B-cell immunodeficiency, periodic fevers, and developmental delay (SIFD) caused by TRNT1 mutation

-

Pearson marrow-pancreas syndrome (PMPS) [18]

Congenital sideroblastic anemia caused by respiratory insufficiency and loss of complex I stability and activity in patient-derived fibroblasts due to NDUFB11 mutations has been reported. [4]

Causes of non-clonal acquired sideroblastic anemia include the following:

-

Nutritional deficiencies (copper, vitamin B-6)

-

Lead poisoning

-

Zinc overdose

-

Alcohol

-

Drugs (eg, antituberculous agents, antibiotics, progesterone, chelators, phenacetin, busulfan)

-

Hypothermia [51]

-

Idiopathic

The medications most often associated with acquired sideroblastic anemia are the antibiotics isoniazid and chloramphenicol. [51] Other implicated antibiotics are linezolid, pyrazinamide, and pristinamycin. [52, 51] There is a report of acquired sideroblastic anemia caused by dolutegravir, an antiretroviral integrase strand transfer inhibitor (INSTI) used in the treatment of HIV. [53]

Clonal sideroblastic anemia

Clonal conditions associated with ring sideroblasts (RS) include myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS), myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPN) and MDS/MPN overlap syndromes. The WHO classification of these conditions is as follows [42, 5] :

Clonal RS myelodysplastic syndromes (MDSs)

-

MDS with ring sideroblasts and single-lineage dysplasia (MDS-RS SLD)

-

MDS with ring sideroblasts and multilineage dysplasia (MDS-RS-MLD)

-

MDS with excess blasts and ring sideroblasts

-

MDS, unclassifiable, with ring sideroblasts

Clonal RS myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs)

-

Essential thrombocythemia with ring sideroblasts

-

Primary myelofibrosis with ring sideroblasts

Clonal RS MDS/MPN overlap syndromes

-

MDS/MPN with ringed sideroblasts and thrombocytosis (MDS/MPN-RS-T)

-

Chronic myelomonocytic anemia with ring sideroblasts

-

Unclassified MDS/MPN with ring sideroblasts

Non-syndromic CSA

This type of CSA is a form of SA that will present as SA alone rather than as part of a clinical syndrome. The various types include the following:

- SIDBA1 is due to various forms of mutations such as missense, nonsense, and promoter/enhanger region mutations. [11] All the mutations within this class show an X-linked inheritence pattern. ALAS2 is the gene most commonly implicated in this type of non-syndromic CSA.

- SIDBA2 is caused by nonsense, frameshift, and missense mutations in SLC25A38, [47] which is needed to transport glycine into the mitochondria. The condensation of glycine with succinyl-coenzyme A (succinyl-CoA) to produce 5-aminolevulinate (ALA) is the first enzymatic step in heme biosynthesis. Thus, the mutations in SLC25A38 result in decreased production of heme.

- SIDBA3 is due to a mutation in the gene GLRX5. This type of SA is very rare, having been reported in only two families to date. It is caused by a homozygous mutation that interferes with the splicing of GLRX5 mRNA, thereby reducing the gene's ability to produce iron-sulfur clusters, which are transporters than help move iron into the cytosol of the mitochondria during heme synthesis. [54]

- SIDBA4 is caused by a mutation of HSPA9. Various mutations occur as in previous types including missense, nonsense, frameshift, and in-frame deletion mutations. The absence of HSPA9 in erythroid cell lines is reported to inhibit the differentiation of erythroid cells

Syndromic CSA

This type of CSA presents as part of a clinical syndrome.

- XLSA/A is caused by a mutation in the ATP-binding cassette transporter (ABCB7). ABCB7 is involved in iron-sulfur cluster biogenesis, which helps to transport iron to the cytosol during heme production. A missense mutation in this gene leads to X-linked sideroblastic anemia with cerebellar ataxia. [54]

- PMPS is due to a deletion of mitochondrial DNA. This causes a defect of the respiratory chain of the mitochondria, [55] which leads (through an unclear mechansim) to refractory sideroblastic anemia and exocrine pancreatic insufficiency. [17]

- TRMA is caused by a mutation of the SLC19A2 gene, which codes for thiamine transporter 1, a protein located on the cell surface that works to bring thiamine into the cell. Thiamine is needed for the production of succinyl CoA, and deficient thiamine leads to megaloblastic anemia, diabetes mellitus, and deafness. [54]

- MLSA1 is due to a missense mutation of PUS1, which helps in the translation of the respiratory chain in the mitochondria. It is not known why it causes sideroblastic anemia. [54]

- MLSA2 is due to a mutation in the YAR2 gene, which encodes mitochondrial tyrosyl transfer RNA synthase. The cause of sideroblastic anemia is also unknown with this type. [54]

- SFID is due to a mutation of the TRNT1 gene, which encodes CCA-adding transfer RNA nucleotidyltransferase. The pathology of sideroblastic anemia in this disorder is unknown. [54]

- NDUFB11 deficiency is due to a deletion of 3 nucleotides in the NDUFB11 gene, leading to phenylalanine deletion in the NDUFB protein and causing normocytic sideroblastic anemia and lactic acidosis. [56]

Epidemiology

In a study of bone marrow biopsies performed in 25 children (age 11 days to 12 years) with unexplained anemia, the prevalence of ringed sideroblasts was 8%. [57]

In France, the prevalence of ringed sideroblasts was 57% in patients with primary MDS. [58] In the United Kingdom, among healthy volunteers undergoing bone marrow biopsy, siderotic granules (not ring sideroblasts) were present in 29% of men and 19% of women. [59]

Although usually manifesting in childhood, congenital X-linked sideroblastic anemia due to ALAS mutation can remain undiagnosed and then present late in the fourth to eighth decades of life. [60, 61] The median age of occurrence of primary acquired sideroblastic anemia is 74 years. [62]

X-linked recessive types of sideroblastic anemia occur more commonly in males. A female would have to inherit an abnormal chromosome from each parent to acquire the disease. Progesterone and pregnancy have been reported to induce relapse of anemia. [63]

No racial predominance is reported in sideroblastic anemia.

Prognosis

The prognosis of patients with sideroblastic anemia is highly variable. Cases with reversible causes such as alcohol or drugs do not appear to carry long-term sequelae. On the other hand, patients with transfusion dependence, those with conditions unresponsive to pyridoxine and other therapies, and those with MDS that develops into acute leukemia have a less bright prognosis.

In congenital sideroblastic anemias, mitochondrial abnormalities may produce neuromuscular dysfunction. In acquired sideroblastic anemias, mortality and morbidity is obviously variable, as some of the causes are reversible. The anemia itself is usually moderate, with hematocrit in the 20-30% range. [64] In idiopathic sideroblastic anemia with MDS, median survival is 38 months, as compared with 60 months in pure sideroblastic anemia (with dyserythropoiesis only, without abnormal megakaryocytic and granulocytic precursors). [65]

Major causes of death in cases of sideroblastic anemia are secondary hemochromatosis from transfusions and leukemia. The patients who die of acute leukemia tend to have a more severe anemia, a lower reticulocyte count, an increased transfusion requirement, and thrombocytopenia.

Thrombocytosis appears to be a relatively good prognostic sign. [66] Patients with no need for blood transfusions are very likely to be long-term survivors, whereas those who become transfusion dependent are at risk of death from the complications of secondary hemochromatosis. [67]

Patient Education

Genetic counseling and an antenatal diagnosis of sideroblastic anemia have in recent years become of practical relevance to families with known cases of congenital sideroblastic anemia. Careful documentation of the clinical outcome of these cases and of other family members is invaluable. [68] .

For patient education resources, see Anemia.

-

Ring sideroblast.

-

Heme synthesis.

-

Sideroblastic anemias: etiologic classification. DIDMOAD = diabetes insipidus, diabetes mellitus, optic atrophy, deafness.

-

Iron and total iron-binding capacity in physiology and pathology.

-

Ringed sideroblast.

-

Heme synthesis pathway.

-

Normochromic vs hypochromic red blood cell (RBC).

-

Pappenheimer bodies seen on giemsa stain.

-

Basophilic stippling in lead poisoning.