Practice Essentials

Ptosis blepharoplasty is the surgical correction of an upper eyelid that is abnormally low in the relaxed primary position. [1] Ptosis can be classified in several ways. The author classifies it as congenital or acquired and as (1) aponeurotic, (2) myogenic, (3) neurogenic, or (4) mechanical.

Ptosis can be subdivided further by levator function into (1) poor (0-5 mm), (2) moderate (5-10 mm), or (3) good (≥ 11 mm).

The goal of ptosis surgery is to recreate as nearly perfect an anatomic result as possible by elevating the position of the lid or lids and by creating a lid fold, if necessary. Selection of surgical repair procedure is decided largely based upon the final classification and subdivision of the particular patient's condition. See the image below.

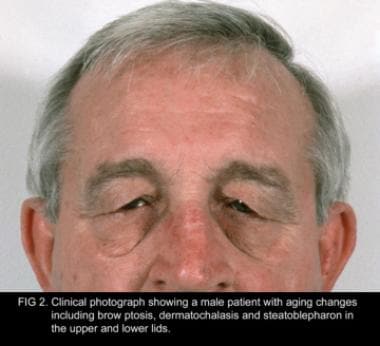

Clinical photograph showing a male patient with aging changes that include brow ptosis, dermatochalasis, and steatoblepharon in the upper and lower lids.

Clinical photograph showing a male patient with aging changes that include brow ptosis, dermatochalasis, and steatoblepharon in the upper and lower lids.

Workup in ptosis

Evaluation of ptosis includes the following:

-

Visual acuity testing

-

Orthoptic evaluation

-

Visual field assessment

-

Slit lamp examination

-

Refraction evaluation

-

Tear function testing

-

Ptosis measurements - Including simple observation and upper lid height

-

Lid contour, lash, and skin evaluation

Management of ptosis

Although many variations of technique and materials for the frontalis sling procedure exist, surgeons generally agree that autologous fascia lata or preserved fascia lata (as a second choice) placed as a double rhomboid, single rhomboid, or triangular sling from the frontalis to the lid produces the best result.

Problem

Congenital

Congenital ptosis is usually a result of fibrous and fatty tissue replacing the normal muscle fibers; these fibers are inelastic and lead to poor function and lagophthalmos on downgaze.

Deciding the best procedure for a patient is easiest when the patient has simple congenital ptosis, whether mild or severe. Patients with congenital ptosis are born with the problem; their ptosis remains relatively constant throughout the first few years of life or until surgery is performed, and their levator function is generally compatible with the degree of ptosis observed clinically.

In general, mild ptosis (1-2 mm) is accompanied by good levator function (>8 mm), moderate ptosis (3 mm) has fair levator function (5-7 mm), and severe ptosis (>4 mm) has poor levator function (< 4 mm).

Levator resection is the procedure of choice for patients with congenital ptosis when reasonable levator function is present. The amount of resection can be small (10-13 mm), medium (14-20 mm), or large (21-26 mm) and can be tailored to be smaller or larger depending on the levator function (ie, a patient with 7 mm of levator function and 3 mm of ptosis requires a smaller resection than a patient with 3 mm of ptosis and 5 mm of levator function).

At the time of surgery, the levator tendon is generally shortened until the lid is at the level the surgeon would like it to be postoperatively (much the way the lid level is set during the frontalis sling procedure). In patients with poorer levator function, setting the lid 1-2 mm higher may be appropriate, since these lids have a tendency to drop postoperatively. The amount of resection necessary in these patients is usually greater than 20 mm.

As a rule, the levators of patients with absent levator function, severe bilateral congenital ptosis, and blepharophimosis syndrome are so abnormal that a frontalis sling is necessary to obtain even passable results. In the past, 3 operative techniques for shortening the levator tendon were widely used. The choice depended on the degree of ptosis, the amount of existing levator action, and the personal preference of the surgeon.

In cases of severe ptosis with poor levator function, an anterior skin approach was used. If the ptosis was moderate and levator action fair or good, Iliff felt his modification of the Blaskovics conjunctival approach to advance the levator tendon was much simpler than the anterior skin approach and that it gave excellent results.

If the ptosis was slight and levator action good, the Fasanella Servat procedure, which excises the tarsus, conjunctiva, Müller muscle, and perhaps levator tendon, gained widespread popularity because of its relatively simple nature. Isolated Müller's muscle resection is a similar procedure that spares the conjunctiva in an effort to decrease the potential for dry eye symptomsis. [2] Some textbooks still discuss the use of the superior rectus muscle in ptosis surgery, but this procedure never should be performed. More recently, the aponeurotic technique for shortening the levator tendon has become the commonly accepted approach.

Congenital Marcus Gunn (jaw-winking) ptosis

Some forms of ptosis warrant individual consideration. Probably the most common and one of the most difficult to manage forms of ptosis is the jaw-winking syndrome (Marcus Gunn phenomenon). All patients with jaw-winking syndrome exhibit a variable degree of ptosis of the involved lid when the eyes are at rest in the primary position. The wink reflex consists of a rapid elevation and retraction of the lid to a higher level than that of the normal fellow lid and an almost equally rapid return to a less elevated level. The involved lid then may remain for a time at the height of the normal lid or may droop to the original ptotic position. The rapidity of the motion produces a bizarre appearance that is disturbing to the patient and observers.

The wink may be produced by sucking, swallowing, chewing, or lateral motion of the jaw to either side. The phenomenon is the result of an abnormal connection between the motor branches of the fifth cranial nerve (the pterygoid branch) and the superior division of the oculomotor nerve, which innervates the superior rectus-levator complex. Studies suggest that a central nervous system abnormality is underlying the anatomic defect in both the affected and clinically uninvolved sides.

The patient (if of appropriate age), parents, and ophthalmologist must decide whether the ptosis or the wink is responsible for the greater cosmetic blemish. If the ptosis is the more striking defect, elevate the lid by shortening the levator aponeurosis. However, this procedure is satisfactory only if the wink is a minimal part of the problem. Because the ptosis is usually mild to moderate, resection is a satisfactory procedure; however, the patient and parents must understand the mechanics of the problem and fully realize that shortening the levator, although improving the appearance of the ptosis in the primary position, also increases the height of excursion of the wink.

If the wink is the major cosmetic blemish, as it often is, it may be corrected in one of several ways. At this time, the most acceptable method of correcting the wink involves severing the levator tendon to destroy its action and then performing a fascia lata sling. Bilateral procedures, which cut the levator tendon of both the affected and the normal lids and suspend both lids from the frontalis muscle, yield a more attractive and symmetric result. Dryden and coworkers have advocated suturing the levator aponeurosis to the linea alba at the upper orbital rim to ensure its deactivation. This procedure does not destroy the levator tendon and muscle, which can be reactivated if, for some reason, reactivation is desired.

Surgery may be delayed for an observation period, since the Marcus Gunn phenomenon has been said to disappear in adulthood. This assumption apparently has been based on the impression that few adults are seen with the condition. In fact, such patients do exist; their apparent scarcity probably is because of prior surgery or a reluctance to continue visiting ophthalmologists for consultation about this problem. Although some decrease in the wink may occur, it does not universally disappear in adulthood.

Acquired

See the list below:

-

Traumatic and iatrogenic ptosis

Adults with acquired ptosis secondary to levator tendon disinsertion or dehiscence may develop the problem either spontaneously or after minor trauma, allergic reactions, or surgery (this is the cause of postoperative, or postcataract, ptosis). The degree may be mild, with only 1-1.5 mm of ptosis, or severe, with a complete ptosis in which the patient is unable to open the eye. Generally, levator function is relatively good, and the ptosis remains essentially the same in both upgaze and downgaze, which readily differentiates it from the inelastic levator muscle typical of congenital ptosis. The lid crease is generally present and is often slightly higher than on the uninvolved side. Additionally, the upper sulcus is frequently deeper than on the uninvolved side, also indicating the diagnosis.

Acquired ptosis with levator dehiscence requires a simple repair to restore normal lid position and function. This is accomplished by reattaching the dehisced edge of the levator aponeurosis to the normal position on the anterior tarsus without resecting any portion of its tendon. Resection of the levator tendon in the presence of a normal muscle leads to overcorrection of the lid position. Overcorrections are observed with some frequency in acquired ptosis because of levator dehiscence, whereas they are difficult to obtain in simple congenital ptosis.

Traumatic ptosis may have 3 possible etiologies. Mild degrees of trauma associated with edema or hemorrhage may produce a levator disinsertion that can be readily repaired using an aponeurotic approach, as described above. Lacerations of the lid may sever the levator tendon, leading to scarring and secondary mechanical ptosis. This problem is best managed by careful repair of the levator aponeurosis at the time of primary repair of the lid injury. If this is not accomplished, often the orbit can be explored at a later time and the levator muscle identified and repaired.

The third major variety of traumatic ptosis involves damage to the nerve supply of the levator muscle. Since the levator and the superior rectus muscle are commonly innervated, such injuries may affect the elevation of the eye, including Bell phenomenon. In this situation, allow at least 6 months to 1 year to pass prior to performing any surgery, since some degree of regeneration often occurs. After this period, a levator resection or sling procedure can be performed, depending on the severity of ptosis and the degree of return of levator muscle function.

If aberrant regeneration is present (as often occurs after damage to the oculomotor nerve) and lid function is significantly abnormal, consider a procedure similar to that described for Marcus Gunn ptosis; however, exercise caution because the abnormal ocular motility may predispose the patient to corneal exposure related to the expected postoperative lagophthalmos.

-

Neurogenic/myogenic ptosis

Acquired ptosis that is not associated with levator tendon dehiscence or trauma is a difficult problem. Myasthenia gravis, ocular-pharyngeal syndrome, idiopathic late-onset familial ptosis, progressive external ophthalmoplegia, and other neurogenic entities fall into this category. The ptosis of myasthenia gravis is usually managed medically and is not discussed in further detail.

The ptoses in the myogenic group are generally progressive and have a high frequency of recurrence despite repeated surgery, including levator resections. When additional surgery is contemplated for patients who have adequate tear secretion and orbicularis muscle function, consider a frontalis sling procedure. Surgery should be performed in these patients with the patient under local anesthesia whenever possible to allow intraoperative adjustment of the lid position with consideration of the degree of lagophthalmos that can be tolerated in that individual. Consider purposeful undercorrection in these patients.

-

Mechanical ptosis: Many patients with tumors of the lid or orbit may present with ptosis, and the surgeon should be aware of such problems when evaluating any patient with acquired ptosis.

-

Blepharophimosis ptosis syndrome

The last major subgroup that presents some difficulty in management is the autosomal dominant–inherited syndrome of blepharophimosis ptosis. Patients with this syndrome have blepharophimosis, severe ptosis (usually with no levator function), epicanthus inversus, and ectropion of the lateral portions of the lower lids. The ptosis is corrected by frontalis fixation at an early age. Canthoplasties may be performed to improve the blepharophimosis. The considerable epicanthus is usually best left until early adolescence, since the degree of this problem tends to diminish with time, and the skin becomes more supple and easy to move. The author has found Mustarde double Z-plasty the most effective method of correcting this problem.

The ectropion of the lateral portion of the lower lids is due to a paucity of skin in the vertical direction and may require skin grafting to repair. A lateral tarsal strip may be necessary in addition to skin grafting to effect proper tightening and elevation in the reconstruction of these lids. If available, although it rarely is in these patients, upper lid skin may be used. Otherwise, a retroauricular skin graft provides the best donor site.

Epidemiology

Frequency

Aponeurotic senile ptosis is the most frequent cause of ptosis, increasing steadily with age. Congenital ptosis is the second most frequent cause. The other causes are relatively infrequent in comparison.

According to statistics from the American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery, in 2016 blepharoplasty was the fourth most commonly performed cosmetic surgical procedure in the United States (173,883 procedures). [3]

Etiology

See Problem.

Presentation

Ptosis is an easily visible phenomenon, and patients often present because of cosmetic concerns. Patients may also present because of a decrease in superior visual field and an inability to read because of severe ptosis in downgaze.

Indications

In most instances, the primary reason for correcting congenital ptosis is cosmetic. Most surgeons agree that significant congenital ptosis should be repaired by age 5 years or before the child begins regular school. An exception to this timing is found in patients with severe bilateral ptosis that interferes with the child's ability to learn how to walk. The levator action in these children is always so poor that a frontalis sling procedure is necessary. Another exception is found in patients with unilateral congenital ptosis of such severity that normal visual development is compromised by total occlusion of the visual axis, in which instance surgical intervention may be indicated shortly after birth. Finally, patients who previously managed bilateral congenital ptosis using a chin-up head position may decompensate with discontinuation of the head-up position; this a sign of development of amblyopia, which must be treated urgently with surgical correction of the ptosis and amblyopia management.

In patients with acquired or secondary ptosis (eg, involutional or traumatic cases, ptosis associated with generalized disease or tumor), surgery often is recommended when the patient's daily activities are compromised by occlusion of the visual axis, superior visual field is lost, or extreme fatigability occurs while reading, among other difficulties. [4]

Vision may be affected in patients with secondary ptosis and sometimes in patients who have slight ptosis. During the preoperative evaluation, the physician must determine if visual or asthenopic components of the ptosis are present that indicate the need for surgery. Thorough documentation of symptoms, field defects, and submission of clinical photographs are now required routinely by third-party payers. [5]

Relevant Anatomy

For purposes of surgery and reconstruction, the lid structures may be divided into anterior and posterior lamellae.

The anterior lamella is the portion of the lid found anterior to the orbital septum and is composed primarily of the skin and the orbicularis oculi muscle. The orbital septum, which originates from the periosteum at the anterior-inferior edge of the orbital rim, hangs down as a curtain across the entire lid to fuse with the levator aponeurosis approximately 3 mm from the upper edge of the tarsus.

The posterior lamella is composed of tarsus, levator aponeurosis, Müller muscle, and conjunctiva. The levator muscle becomes tendinous at approximately the level of the superior rectus muscle insertion and extends anteriorly and then inferiorly to insert into the lower third of the anterior tarsal surface. The Whitnall ligament (superior suspensory ligament of the orbit) is a condensation of connective tissue fibers at the level of the junction of levator muscle and its aponeurosis, which in most instances is anterior to the levator, but it sometimes surrounds the muscle like an envelope. The Whitnall ligament is often missed by the ophthalmic surgeon at the time of surgery. It extends temporally to the lateral orbital rim through the orbital lobe of the lacrimal gland and nasally to the trochlear fascia.

The levator aponeurosis, as it passes inferiorly, fans out nasally and temporally to form the nasal and temporal horns. The temporal horn separates the palpebral from the orbital lobe of the lacrimal gland. These horns must often be cut at the time of surgery, especially when they act as check ligaments to the levator action.

At about the level of the upper border of the tarsus, aponeurotic fibers arise that extend through the orbicularis muscle to insert into the dermis. These fibers produce the lid crease. A few aponeurotic fibers also extend to the conjunctiva of the upper cul-de-sac to provide its support and to allow for conjunctival retraction with upward rotation of the eye. The levator tendon is separated from the orbital septum by the preaponeurotic fat, which is an important landmark in the exposure of the tendon during ptosis surgery. The tendon may be somewhat variable in length, usually measuring 14-20 mm.

The Müller muscle arises from the inferior surface of the levator originating at the level of the Whitnall ligament and lying between the aponeurosis and the conjunctiva. It passes anteroinferiorly to insert in the upper edge of the tarsus. The Müller muscle is thin and has a slightly darker color than the levator aponeurosis and levator muscle when seen during surgery.

In addition, the peripheral arcade of vessels at the upper edge of the tarsus courses through the Müller muscle and marks its anatomic location. The levator muscle is innervated by a branch of the superior division of the oculomotor nerve (cranial nerve III), which courses through the belly of the superior rectus muscle found beneath it. In congenital ptosis, histologic evidence of muscular dystrophy is present, and fatty tissue and fibrosis replace the levator muscle fibers. As the degree of fibrosis increases, the ptosis becomes more severe. Absence of muscle fibers in patients with congenital ptosis has been documented.

Contraindications

Some ophthalmologists feel that the presence or absence of Bell phenomenon is of significant importance in ptosis surgery. In most circumstances, its absence is not a contraindication to surgery in patients with congenital ptosis. However, exercise extreme caution in patients with processes (eg, thyroid myopathy, progressive external ophthalmoplegia) or dystrophies in which a poor Bell phenomenon, decreased random eye movements during sleep, and poor orbicularis muscle function may exist and produce lagophthalmos and corneal exposure. Loss of the blink reflex or corneal sensitivity, paralysis of the orbicularis, and significant keratitis sicca are definite contraindications to surgery.

-

Clinical photograph showing a male patient with aging changes that include brow ptosis, dermatochalasis, and steatoblepharon in the upper and lower lids.