Background

The modern era of nasal reconstruction has brought significant advancements and offers unparalleled opportunities for reconstructive surgeons to maximize functional and aesthetic outcomes. The forehead flap has been used for many centuries and remains a workhorse flap for major nasal resurfacing. This article explores the history of forehead flap surgery, contemporary concepts in flap design, surgical steps, and potential complications.

History of the Procedure

Nasal reconstruction originated almost 3000 years ago in India, where large cheek flaps were developed to reconstruct noses. Nasal amputation was a common form of social punishment for various crimes, from theft to adultery, thus giving rise to a large group of individuals in need of total or subtotal nasal reconstruction. A seventh century Indian medical document, the Sushruta Samita, describes a technique using a flap from the forehead for nasal restoration. In the 15th century, Antonio Branca of Italy discovered an Arabic translation of the Sushruta Samita and is believed to be the first to perform a similar procedure outside of India. In Europe, Italian surgeons used a pedicled flap from the medial surface of the upper arm for nasal reconstruction.

In the late 18th century, JC Carpue found a description of this Indian technique, giving rise to the modern era of nasal resurfacing with the use of a pedicled forehead flap. Carpue first practiced these techniques on cadavers and later applied them to live patients, eventually publishing his results. His writings soon spread across Europe and to America, revolutionizing nasal reconstruction. Carpue's basic techniques laid the foundation for modern nasal reconstruction for the next century.

These techniques were modified further and popularized by other surgical giants. Kazanjian advanced the development of the forehead flap by advocating primary closure of the forehead donor site. [1] Millard, in the 1960s and 1970s, used a characteristic gull-wing design with lateral extensions for alar reconstruction and extended the pedicle incisions below the brow to provide greater flap length. [2, 3] Burget and Menick made further contributions to the design by emphasizing aggressive thinning of the skin paddle, narrowing the pedicle base for easier rotation and length, and modifying defects to follow aesthetic subunits of the nose. [4] The midline forehead flap is based on a narrow pedicle centered on the medial brow area, often capturing the proximal supratrochlear artery. The base of the pedicle is no more than 1.5 cm and often close to 1.2 cm.

The skin paddle can be positioned in the precise center of the forehead. An advantage of placing the skin paddle in the midline rather than paramedian is that the pedicle is slightly longer and the donor site scar is in a more aesthetic midline position. The vertical donor site scar can be more inconspicuous when centered in the midforehead area.

Problem

Nasal reconstruction poses the challenges of restoring aesthetics in a prominent area on the face while preserving function. A full-thickness defect requires a multilayered reconstruction that addresses each of the 3 separate layers of the nose (ie, cutaneous surface, internal lining, structural support). Once structural grafting is placed, its covering must be durable and of similar thickness and texture to native nasal skin and it must have its own blood supply. Ideally, this is accomplished with minimal donor site morbidity and with reproducible dependability.

Epidemiology

Frequency

Nasal defects may occur from a variety of etiologies, the most common being related to cutaneous malignancies and their excision. The incidence of nonmelanotic skin cancers is rising, with the estimation being that more than 3 million Americans per year are affected by these disorders. [5] Mohs surgical excision remains the procedure of choice for management of infiltrating or complex skin cancers, and it creates nasal defects of different sizes. Traumatic causes of nasal defects also occur and may require major repair with a forehead flap.

Indications

Numerous techniques are available for nasal reconstruction, but the forehead flap remains the criterion standard technique for large cutaneous defects. Not only does it provide the optimal color and texture match to the native nasal skin, but it carries its own vascular supply and can nourish underlying grafts and tenuous flaps. A single forehead flap can be used for resurfacing the entire nose, from ala to ala. Its dependability and consistent anatomy make the forehead flap a workhorse for major nasal restoration, setting the bar for an aesthetically inconspicuous reconstruction and restoration of function. The donor site on the forehead is similarly acceptable.

No absolute indications for a forehead flap exist because patient considerations may override the selection of this flap. The forehead flap is more complex and more involved than smaller local flaps, requiring a second stage at roughly 3 weeks after the original flap transfer. The overall health of the patient, including his/her surgical candidacy, must be reviewed.

Other considerations include patients' aesthetic expectations (recognizing that simpler methods may leave contour problems), poor color match, or some degree of alar base distortion and contraction. These outcomes can be anticipated when using a skin graft for a deeper defect or when pushing the limits of a local nasal flap (creating excessive tension). When these aesthetic results from these simpler flaps are unacceptable, the forehead flap is indicated. For most large or complex nasal defects, the forehead flap provides the most dependable and aesthetically acceptable reconstruction.

Generally, cutaneous defects involving the nasal tip fare poorly with skin grafts, even thicker ones, and either a local flap or a forehead flap is indicated. Conversely, native nasal skin of the upper third is much thinner and amenable to grafts. Defects larger than 1.5 cm may exceed the limits of a local flap and often do better with the interpolated forehead flap. Defect size is influenced by the consideration of the aesthetic nasal subunits that are often excised when involved with the primary defect. Finally, any reconstruction that requires structural grafting necessitates a resurfacing flap that has its own blood supply; this represents a common indication for the forehead flap.

Relevant Anatomy

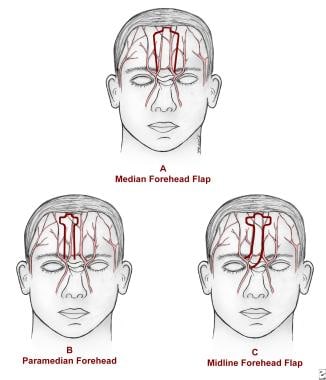

Forehead flaps are based on the robust vasculature to the forehead via the supraorbital, supratrochlear, and terminal branches of the angular and dorsal nasal vessels. The first anatomic point involves forehead flap terminology. The median forehead flap is harvested from the mid forehead and has a wide pedicle based in the center of the forehead, which originally captured both supratrochlear vessels as seen in the image below.

A is a median forehead flap over the forehead vasculature. B is the paramedian forehead flap over the forehead vasculature. C is the midline forehead flap over the forehead vasculature.

A is a median forehead flap over the forehead vasculature. B is the paramedian forehead flap over the forehead vasculature. C is the midline forehead flap over the forehead vasculature.

The paramedian forehead flap is designed around a narrower pedicle based on the medial brow area over the superior/medial orbital rim. The skin paddle and pedicle are aligned vertically, with the supratrochlear notch in the paramedian position of the forehead as seen in the image above. The resultant donor scar is oriented vertically and aligns with the medial brow. [6]

The midline forehead flap is a hybrid of median and paramedian flaps, with the skin paddle harvested from the precise center of the forehead. The associated pedicle runs obliquely and is based on a unilateral supratrochlear vessel and collaterals from the medial brow area as seen in the image above. Collateral flow from the angular artery can contribute to significant perfusion pressure at the pedicle base. The body of the midline flap is harvested from the precise center of the forehead, allowing a less conspicuous donor scar that is more consistent with facial aesthetic units. The pedicle may be based on either side, allowing choices between flap length and the arc of pedicle rotation.

The primary blood supply to the forehead flap comes from both the supratrochlear artery and the collateral flow at the medial brow region (terminal branch of the angular artery). This is a rich anastomoses among the supratrochlear, dorsal nasal, and angular arteries, providing a robust perfusion pressure; thus, it drives the vascular design of the forehead flap. The pedicle base is usually narrow but captures this complex anastomosis at the superior/medial orbital rim. A prominent central vein should be incorporated into the pedicle design. The precise anatomic anastomosis between the named major vessels in the medial brow region varies.

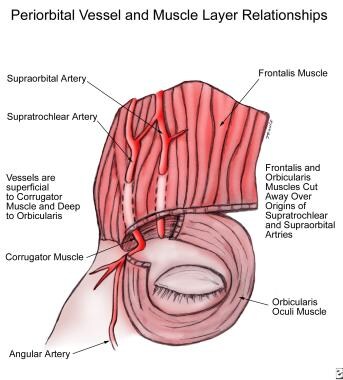

The supratrochlear artery exits at the superior and medial corner of the bony orbit, approximately at the medial point of the eyebrow. It passes superficial to the corrugator muscle and deep to the orbicularis, ascending in a paramedian position for approximately 2 cm before piercing the frontalis muscle as seen in the image below.

The anatomic relationship of the supratrochlear vessels and the periorbital and forehead musculature.

The anatomic relationship of the supratrochlear vessels and the periorbital and forehead musculature.

The supratrochlear artery then travels superiorly in the subcutaneous plane, above the galea/frontalis muscle, maintaining numerous anastomoses with the contralateral vessels. The terminal angular artery may ascend the forehead as a distinct vessel or communicate with the ipsilateral supratrochlear artery. The paired dorsal nasal arteries usually merge to form a single central artery of the forehead.

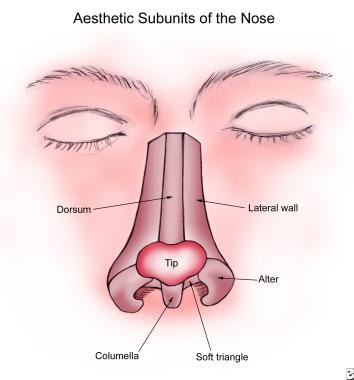

Forehead flap design is influenced by nasal anatomy. The thickness and mobility of the nasal skin varies across different anatomic sites. The skin overlying the dorsum and sidewalls is thin and mobile, whereas the skin of the nasal tip and nasal alae is thicker and less mobile. Nasal topography is a combination of convex and concave surfaces that provide the foundation of nasal aesthetic subunits as seen in the image below. These subunits are the block images the casual eye detects upon viewing a nose. These images are then synthesized into the expected and familiar nose shape. Borders between these subunits tend to be inconspicuous, and they provide optimal scar-concealment areas.

When planning a nasal defect reconstruction, one often replaces the entire involved aesthetic subunit rather than just filling in the original hole. Strategically controlling the shape of the defect, flap shape, and, ultimately, the resultant scars, leaves the optimal reconstruction that is as inconspicuous as possible.

Contraindications

A contraindication to the forehead flap may be anatomic issues relating to the axial blood supply to the skin paddle. Deep, horizontal scars across the base of the forehead may preclude the successful mobilization of this flap. One must inspect the mid-forehead area closely, especially because most patients have a history of prior cutaneous malignancies (and are at risk for future recurrences). Small superficial scars may be acceptable, but scars that extend to the galea create a significant barrier to the blood supply through the pedicle.

A history of previous forehead flaps is not necessarily a contraindication. Certainly, one would base the flap on contralateral side if one previous flap has been elevated. Even if both sides have been used, one may mobilize a third flap due to the robust collateral blood supply at the medial brow area and the angular artery.

Additional contraindications are based on the patient's comorbidities and his or her ability to tolerate surgery. Potential clotting problems or easy bruising indicates a potential surgical risk. Additionally, the patient's general health status may indicate an anesthetic risk and should be fully considered.

Patient expectations are a significant consideration. Some patients may not be particularly concerned with their appearance and want little or no intervention. They may prefer to keep the reconstruction as simple as possible at the expense of the aesthetic appearance or even function.

Emphasize the significant postoperative care needed for the pedicle. A strong possibility of poor patient compliance may contraindicate surgery.

-

A is a median forehead flap over the forehead vasculature. B is the paramedian forehead flap over the forehead vasculature. C is the midline forehead flap over the forehead vasculature.

-

The anatomic relationship of the supratrochlear vessels and the periorbital and forehead musculature.

-

Aesthetic subunits of the nose.

-

Photograph on left depicts a nasal defect following Mohs surgery. Center photograph shows the defect defined in terms of subunits involving the ala, nasal tip, and cheek. Photograph on right shows the completion of the aesthetic subunits and advancement of the cheek flap up to the nasal facial sulcus.

-

A is a nasal defect template (from suture package). B is the template transferred to the precise midline of the forehead.

-

A is a flap elevation in the subcutaneous plan, superficial to the frontalis muscle. B is a selective thinning to best match normal nasal skin thickness.

-

Periosteum incorporated into the pedicle base.

-

Midline forehead flap transferred to the nose.

-

The left photograph is the planned pedicle division. The right photograph is the pedicle stump partially inset into the glabella.

-

The left photograph shows a 2-year postoperative frontal view. The right photograph is an oblique view of the same patient.

-

Large nasal defect following excision of skin malignancy.

-

Frontal postoperative view.

-

Aesthetic units drawn.

-

Midline forehead flap outlined.

-

Close oblique postoperative view.