History of the Procedure

The cricopharyngeus muscle, also known as the upper esophageal sphincter (UES), was first described by Valsalva in 1717. Over time, an association between dysfunction of the cricopharyngeus and pharyngeal diverticula was identified. [1] In 1946, Lahey proposed dilatation of the cricopharyngeus for the treatment of pharyngeal diverticula, which greatly added to physicians' understanding of upper esophageal dysphagia disorders. [2] In 1950, Asherson proposed the term cricopharyngeal achalasia to denote a persistent spasm of the UES that causes symptoms of dysphagia. Several subsequent authors have proposed cricopharyngeal myotomy for the management of upper esophageal and pharyngeal dysphagia in the setting of polio, degenerative neurologic disorders, and strokes and after head and neck surgery.

See the image below.

Problem

Cricopharyngeal myotomy, or surgical sectioning of the cricopharyngeus muscle, has been advocated for the treatment of cricopharyngeal spasm that causes cervical dysphagia.

Epidemiology

Frequency

The exact incidence of cervical dysphagia caused by cricopharyngeal dysfunction is unknown. The lack of epidemiologic data results from the significant controversy regarding the diagnostic criteria required for proper use of the term cricopharyngeal dysfunction (ie, achalasia); some authors base the diagnosis solely on symptoms, while others hinge the diagnosis on highly specialized radiologic and invasive probe studies. Although the exact incidence of cricopharyngeal dysfunction is unknown, the literature reports cricopharyngeal achalasia as the primary cause of or as a contributor to dysphagia in 5-25% of patients being evaluated for clinical symptoms of dysphagia.

Etiology

Cricopharyngeal achalasia may be primary or secondary. Primary cricopharyngeal achalasia implies that the abnormality that leads to the persistent spasm or failure of relaxation of the cricopharyngeus muscle is confined to the muscle, with no underlying neurologic or systemic cause. This primary group can be further subdivided into primary cricopharyngeal achalasia with no underlying cause (ie, idiopathic) or cricopharyngeal achalasia caused by intrinsic disorders of the cricopharyngeus muscle (eg, polymyositis, muscular dystrophy, hypothyroidism, inclusion body myositis).

In many instances, the cricopharyngeal spasm may be secondary to neurologic disorders such as polio, oculopharyngeal dysphagia, stroke, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). Peripheral neurologic disorders,such as diabetic neuropathy, myasthenia gravis, and peripheral neuropathies, can also cause cricopharyngeal dysfunction.

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of cervical dysphagia, as it relates to cricopharyngeal dysfunction, remains unclear. Three main theories have been proposed to explain the relationship between cricopharyngeal dysfunction and dysphagia. The most widely held theory reasons that the cricopharyngeus, which is normally in a state of tonic contraction, fails to relax to allow the passage of the food bolus into the cervical esophagus. This theory has been supported by radiologic and manometric data. Other investigators have identified patients with hypertensive cricopharyngeus muscles, which are abnormally hypertonic during the swallow. Finally, others have identified a relative lack of coordination between the pharyngeal propulsion and the cricopharyngeal relaxation.

These debates are likely to continue given that the full physiologic measurement of the cricopharyngeus during swallowing is difficult and invasive. Furthermore, the presence of the manometric catheter may actually stimulate cricopharyngeal hypertonicity because the catheter irritates the esophageal lumen. Finally, recent work has elucidated a potential role of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) as a cause for cricopharyngeal spasm.

Presentation

The clinical presentation of patients with cricopharyngeal achalasia may be quite variable. Most patients primarily experience food sticking or catching in the lower third of the neck. These patients often point to the cricoid region in their description of the dysphagia. Patients may also experience accompanying symptoms of heartburn, choking, and pain with swallowing. Less common symptoms include dysphonia, a globus sensation, and pressure in the neck during deglutition. Symptoms have often been present for months to years. In cases related to neurologic causes, the diagnosis of cricopharyngeal achalasia may postdate the neurologic event or diagnosis by several months or years. A history of pneumonia or aspiration pneumonia should be elicited.

Indications

The indications for cricopharyngeal myotomy in the treatment of cervical dysphagia are usually based on a combination of patient symptoms, findings from radiologic studies, and, less frequently, manometric information. Before surgical intervention, if possible, aggressively manage underlying etiologies such as neurologic disorders and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). Myotomy may be considered if conservative measures fail and radiologic evidence exists on the video fluoroscopic swallowing study (VFSS) of cricopharyngeal dysfunction that leads to a hesitation of bolus passage.

Manometry may also lend some information, and those patients with clear-cut cricopharyngeal spasm with manometric evidence of hypertonic contraction of the cricopharyngeus tend to have better outcomes. Cricopharyngeal myotomy may also be considered in the absence of clear-cut radiologic data when patients present with significant aspiration or weight loss caused by clinically evident cervical dysphagia, especially when other methods of treatment have failed.

Relevant Anatomy

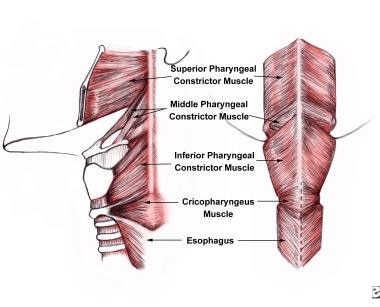

The cricopharyngeus muscle is a true sphincter composed of striated muscle. Arising from the lateral borders of the cricoid cartilage, the muscle fibers form a sling around the wall of the superior aspect of the cervical esophagus. The cricopharyngeus muscle is bordered superiorly by the inferior constrictor muscle and merges inferiorly with the muscular layers of the cervical esophagus. The muscle is innervated primarily by the vagus nerve, both by branches from the pharyngeal plexus and by neuronal branches from the recurrent laryngeal nerve. Therefore, the recurrent laryngeal nerves lie in close proximity within the surgical.

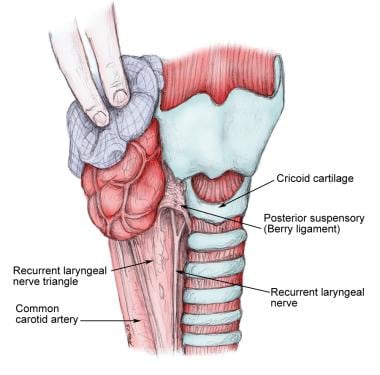

The main trunk of the recurrent laryngeal nerve lies in a triangle bound laterally by the common carotid artery, the internal jugular vein, and the vagus nerve and medially by the trachea and esophagus. The recurrent nerve passes under the posterior suspensory ligament of Berry (located on either side of the trachea, extending from the cricoid cartilage and the first 2 tracheal rings to the posteromedial aspect of the thyroid gland), before entering the larynx (see the image below).

For more information about the relevant anatomy, see Vagus Nerve Anatomy and Esophagus Anatomy.

Contraindications

Cricopharyngeal myotomy is contraindicated when the patient has a known tumor that involves the cervical esophagus or an otherwise correctable mucosal disease that involves the cervical esophagus or hypopharynx. Cricopharyngeal myotomy is also relatively contraindicated in patients who have undergone radiation therapy for head and neck cancer because the cricopharyngeus may be fibrotic and less apt to release when sectioned. Other authors consider cricopharyngeal myotomy to be relatively contraindicated in patients with progressive neurologic disorders such as bulbar palsy.

Traditionally, cricopharyngeal myotomy has been thought to afford limited success in the setting of oculopharyngeal muscular dystrophy. However, recent data suggest that it can be effective for several years after surgery with acceptable rates of recurrent dysphagia at 3 years. [3] Finally, cricopharyngeal myotomy may also be relatively contraindicated in the setting of significant gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). Although this is controversial, massive reflux may predispose the patient to significant laryngopharyngitis and subsequent dysphonia.

-

Anatomic location of the cricopharyngeus muscle.

-

Typical appearance on swallowing videofluoroscopy of cricopharyngeal achalasia. Note the prominent posterior indentation in the barium column at the level of the larynx.

-

Relation of the recurrent laryngeal nerve to the cricoid cartilage.