Practice Essentials

Subglottic stenosis, partial or complete narrowing of the subglottic area, may be congenital or acquired. The problem is rare and challenging, affecting soft tissue and cartilage support.

Iatrogenic injuries cause most of the problems seen. Often, subglottic stenosis has an insidious onset, and early manifestations are usually mistaken for other disorders (eg, asthma, bronchitis).

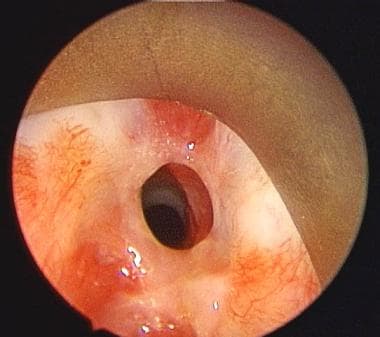

An image depicting subglottic stenosis can be seen below.

Workup in subglottic stenosis

Laboratory studies

In the absence of a history of prior trauma or when suggested by other findings, evaluate for inflammatory or infectious causes, including the following:

-

Wegener granulomatosis

-

Relapsing polychondritis

-

Syphilis

-

Tuberculosis

-

Sarcoidosis

-

Leprosy

-

Diphtheria

-

Scleroma

Imaging studies

Standard chest radiographs can often provide a great deal of information regarding the tracheal air column. Radiographic anteroposterior filtered tracheal views and lateral soft tissue views of the neck provide specific information regarding the glottic/subglottic air column.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is useful in evaluating length and width of the stenotic region by means of coronal and sagittal views.

Computed tomography (CT) scanning is not as helpful as MRI because its views are generally only in the axial plane. Thin cuts (1 mm) with sagittal and/or coronal reconstructions may be helpful, however.

Other

Videostrobolaryngoscopy is extremely helpful in evaluating the glottic and supraglottic larynx for possible concomitant injury.

Visualization of the larynx by flexible fiberoptic or rigid telescopic (90- or 70-degree scopes) in the clinic is crucial to the evaluation of airway lesions.

Management of subglottic stenosis

Medical therapy

Antireflux management includes the following

-

Proton pump inhibitor (eg, omeprazole, 20 mg PO bid or equivalent)

-

Ranitidine, 300 mg PO bid-qid, if proton pump inhibitor is not an option

-

Dietary and lifestyle modification

Transcervical or transoral (via a channeled scope) injection of steroids such as triamcinolone acetonide (Kenalog-40) is being used by many centers, with good early results in the control of subglottic inflammation and, in some cases, diminution of the subglottic scar.

Surgical therapy

Surgical procedures for subglottic stenosis include the following:

-

Long-term tracheostomy

-

Long-term intraluminal stent

-

Endoscopic repair

-

Open repair

-

Anterior cricoid division with interposition graft (eg, hyoid-sternohyoid muscle, split clavicle muscle, rib)

-

Anterior and/or posterior cricoid split with stenting

-

Anterior laryngofissure with anterior lumen augmentation

-

Resection of stenotic segment with end-to-end repair

-

Staged free-graft repair

Etiology

Congenital

Stenosis is said to be congenital in the absence of a history of intubation or other acquired causes. Congenital laryngeal webs account for approximately 5% of congenital anomalies of the larynx, with 75% occurring at the glottic level and the rest occurring at the subglottic or supraglottic level. Most severe cases are diagnosed in childhood.

Acquired

Trauma is the most common cause of stenosis in both children and adults. Approximately 90% of all cases of acquired chronic subglottic stenosis in children and adults result from endotracheal intubation. The reported rate of stenosis following intubation ranges from 0.9-8.3%.

Intubation causes injury at the level of the glottis due to pressure between the arytenoid cartilages. Intubation causes injury in the subglottis due to the complete cartilaginous ring or can cause injury distally in the trachea. Pressure and/or motion of the tube against the cartilage framework may cause ischemia and necrosis.

Duration of intubation is the most important factor in the development of stenosis. Severe injury has been reported after 17 hours, but it may occur much sooner. A 7-10 day period of ICU intubation is acceptable, but the risk of laryngotracheal injury increases drastically after that.

Size of the tube is also important. Tubes should be no larger than 7-8 mm in internal diameter for adult males. Tubes should be no larger than 6-7 mm in internal diameter for adult females. The size of the endotracheal tube needed correlates best with the patient's height.

Stenosis could also be secondary to foreign body, infection, inflammation, or chemical irritation. Respiratory epithelium is susceptible to injury. Initial edema, vascular congestion, and acute inflammation can progress to ulceration and local infection with growth of granulation tissue. Finally, fibroblast proliferation, scar formation, and contracture can occur and result in stenosis.

Systemic factors may increase the risk of injury and include the following:

-

Gastric acid reflux

-

Chronic illness

-

Immunocompromised patient

-

Anemia

-

Neutropenia

-

Toxicity

-

Poor perfusion

-

Radiation therapy

Other causes include the following:

-

External trauma, penetrating and blunt

-

Tracheotomy, especially a high tracheotomy or cricothyroidotomy

-

Percutaneous tracheotomy (This has an emerging role as a cause.) [1]

-

Chondroradionecrosis after radiation therapy; may occur up to 20 years later

-

Chronic infection

Chronic inflammatory diseases include the following:

-

Sarcoidosis

-

Relapsing polychondritis

-

Chronic inflammation secondary to gastroesophageal reflux and other conditions

-

Neoplasm

A retrospective study by Fang et al found that among 41 patients with idiopathic subglottic stenosis who underwent esophageal pH impedance testing, 19 (46.3%) had gastroesophageal reflux disease, including 15 (36.6%) who had a predominantly upright reflux condition. [2]

A study by Gnagi et al found that time to diagnosis differed significantly between patients with acquired subglottic stenosis and those with idiopathic subglottic and tracheal stenosis. While 32% of the acquired stenosis patients were diagnosed within 3 months of symptom onset, just 2% of the other group were diagnosed within this time. The study involved a total of 160 patients. [3]

Pathophysiology

Congenital stenosis has two main types, membranous and cartilaginous.

In membranous stenosis, fibrous soft tissue thickening is caused by increased connective tissue or hyperplastic dilated mucus glands with absence of inflammation. Membranous stenosis is usually circumferential and may extend upward to include the true vocal folds.

In cartilaginous stenosis, a thickening or deformity of the cricoid cartilage most commonly occurs, causing a shelflike plate of cartilage and leaving a small posterior opening. Cartilaginous stenosis is less common than membranous stenosis.

Acquired subglottic stenosis is secondary to localized trauma to subglottic structures. Usually, injury is caused by endotracheal intubation or high tracheostomy tube placement. If irritation persists, the original edema and inflammation progress to ulceration and granulation tissue formation. This may or may not involve chondritis with destruction of the underlying cricoid cartilage and loss of framework support.

When the source of irritation is removed, healing occurs with fibroblast proliferation, scar formation, and contracture, leading to stenosis or complete occlusion of the airway.

A study by D’Oto et al indicated that in patients with idiopathic subglottic stenosis, the rates of tobacco use and type 2 diabetes mellitus are higher in persons aged 65 years or older than in younger individuals. This may demonstrate that idiopathic subglottic stenosis has a different pathophysiology in older patients than it does in persons below age 65 years. Nonetheless, although type 2 diabetes has been linked to delayed and aberrant wound healing, the investigators admit that because the incidence of diabetes tends to be higher in older individuals in general, those results may have limited clinical significance. However, the greater rate of current and former tobacco use in the elderly may also indicate aberrant healing as a source of the stenosis. [4]

Presentation

Adults with mild congenital stenosis are usually asymptomatic, and they are diagnosed after a difficult intubation or while undergoing endoscopy for other reasons.

Patients with acquired stenosis are diagnosed from a few days to 10 years or more following initial injury. The majority of cases are diagnosed within a year. Symptoms include the following:

-

Dyspnea (may be on exertion or with rest, depending on severity of stenosis)

-

Stridor

-

Hoarseness

-

Brassy cough

-

Recurrent pneumonitis

-

Cyanosis

Many patients would have been diagnosed with asthma and recurrent bronchitis prior to discovery of stenosis. A high index of suspicion is warranted with the onset of respiratory symptoms following intubation, regardless of the duration of intubation.

Indications

Indications for treatment are to improve compromised airways and progress toward decannulation. Speedy intervention prior to cartilage damage or scar contracture is preferred when the diagnosis is made early.

Relevant Anatomy

The subglottic area is circumferentially bound by the cricoid cartilage, which is part of the larynx. The adult trachea is 10-13 cm long and 17-24 mm in diameter and extends from the inferior border of the cricoid cartilage to the carinal spur.

The first tracheal cartilage is partly inset in the lower border of the cricoid and, on occasion, may be fused with it. All of the tracheal rings are incomplete posteriorly.

Primarily, arterial supply to the larynx comes from branches of the superior and inferior thyroid arteries. The superior thyroid artery sends a superior laryngeal branch through the thyrohyoid membrane. The inferior thyroid artery sends an inferior laryngeal branch with the recurrent laryngeal nerve to enter the larynx near the cricothyroid joint.

The tracheal blood supply is segmental. Branches of the inferior thyroid artery supply the upper trachea. Branches of the bronchial arteries, with contributions from subclavian, supreme intercostal, internal thoracic, and innominate arteries, supply the lower trachea. The branches arrive to the trachea via lateral pedicles.

Sensory innervation to the subglottic mucosa is by the recurrent laryngeal nerve. The thyroid gland is adherent to the trachea at the second and third tracheal rings, but the lateral lobes overlie the cricoid cartilage and can approximate the lower lateral thyroid laminae.

Contraindications

Most contraindications are relative and include the following:

-

General medical state of the patient precluding general anesthesia

-

Factors affecting wound healing (eg, diabetes mellitus)

-

Active inflammatory state (eg, Wegener granulomatosis); relative contraindication to surgical intervention and warrants medical treatment

-

Any active infection at the site; should be medically managed

Contraindications specific to long-term tracheostomy are debatable and include the following:

-

Circumferential scarring with cicatricial contracture

-

A scar greater than 1 cm in vertical height

-

Loss of cartilage

-

History of severe bacterial infection associated with tracheostomy

-

Posterior glottic stenosis with arytenoid fixation

-

Prior radiotherapy (relative contraindication)

Contraindications reported for open repair include the following:

-

Contraindication to general anesthesia

-

Need for tracheotomy

-

Significant gastroesophageal reflux

-

Preoperative view of subglottic stenosis via an endoscopic approach.

-

Postoperative view of subglottic stenosis after 4-quadrant carbon dioxide laser division and endoscopic balloon dilation. Note the excellent view of distal airway.