Practice Essentials

A laryngeal fracture can occur following direct trauma to the neck region and may lead to life-threatening airway obstruction. For this reason, a patient suspected of having a fractured larynx should be treated in an emergent manner. [1, 2, 3]

A traumatically injured patient may present with many distracting injuries. Appropriate treatment of this patient requires that airway patency be the first priority. Injury to the larynx may range from simple mucosal tears to fractured and comminuted cartilage. Any combination of injuries along this continuum can result in a precipitous airway emergency.

Although advancements in imaging techniques have improved their diagnosis, the rarity of laryngeal fractures and the limited experience of otolaryngologists have made this a challenging entity to manage. An organized approach to laryngeal fractures can prevent misdiagnosis and inadequate management.

Signs and symptoms of laryngeal trauma

Common presenting symptoms in patients with laryngeal trauma include the following:

-

Hoarseness

-

Neck pain

-

Dyspnea

-

Dysphonia

-

Aphonia

-

Dysphasia

-

Odynophonia

-

Odynophagia

Common signs of laryngeal injury include the following:

-

Stridor

-

Subcutaneous emphysema

-

Hemoptysis

-

Hematoma

-

Ecchymosis

-

Laryngeal tenderness

-

Vocal cord immobility

-

Loss of anatomical landmarks

-

Bony crepitus

Workup in laryngeal fracture

Laryngeal fractures are usually suspected based on symptoms and physical findings, but direct visualization of the larynx is critical to define the extent and location of injury.

Computed tomography (CT) scanning is the imaging modality of choice to assess laryngeal anatomy. [4, 5, 6]

Generally, in the setting of a laryngeal fracture, chest and cervical spine radiographs are obtained as well, to exclude associated cervical injuries.

The following procedures are also used to evaluate patients with suspected laryngeal trauma:

-

Fiberoptic nasopharyngoscopy

-

Direct laryngoscopy

-

Bronchoscopy

-

Esophagoscopy

Management of laryngeal fracture

Medical therapy

For minor injuries in which edema, hematoma, or certain small insignificant mucosal tears are identified without evidence of other injury, medical treatment is appropriate. Mucosal tears of less than 2 cm have been treated effectively without surgical intervention. [7]

Bed rest is recommended for patients treated medically for laryngeal trauma, with the head of the bed elevated 30-45°. Voice rest is recommended to minimize edema, hematoma formation, and subcutaneous emphysema. Humidified air reduces crust formation and transient ciliary dysfunction.

Surgical therapy

Regardless of the operative method used, the goal of surgical intervention is to restore the three primary functions of the larynx: breathing, phonating, and swallowing.

Traditionally, wire sutures have been used to immobilize reduced laryngeal cartilage fractures. Many surgeons, however, now use metal alloy plates (miniplates) for repairing laryngeal fractures. Miniplates have been shown to effectively stabilize the laryngeal architecture and reshape the larynx back to its preinjury state. [8, 9]

Subsequently, the use of absorbable miniplates was introduced. These plates have been found to be just as safe, effective, and manageable as their alloy counterparts.

Epidemiology

Frequency

A laryngeal fracture is a rare condition, occurring in approximately 1 per 137,000 inpatient visits, [10] 1 patient per 14,000-42,000 emergency department visits, [11] and less than 1% of all blunt traumas. [12] Using the Nationwide Emergency Department Sample, Sethi et al determined that between 2009 and 2011, there were 3102 cases of laryngeal fracture diagnosed in US emergency departments. [13]

The rarity of this condition is likely due to the protected location of the larynx, with the rigid cervical spine posterior and the mandible hanging in a superior and anterior position. This protection is amplified in the pediatric population, secondary to the high position of the larynx and its elastic nature. In addition, the decrease in traumatic motor vehicle injuries because of increased seatbelt and supplemental restraint system use contributes to the rarity of laryngeal trauma. Less than 50% of all laryngeal traumas are thought to result in cricoid injury. [14] In older persons, a predisposition to comminuted fractures is attributed to calcification.

The most common associated injuries with laryngeal fractures are intracranial injuries (13%), open neck injuries (9%), cervical spine fractures (8%), and esophageal injuries (3%). [10] A retrospective study by Passias et al, using the National (Nationwide) Inpatient Sample, found that injuries commonly occurring concurrently with traumatic cervical spine fractures include fractures of the rib, sternum, larynx, and trachea, with an incidence of 19.6% between 2005 and 2013. [15]

Sex

Females tend to have slimmer, longer necks, predisposing them to a higher susceptibility to laryngeal injury, in particular supraglottic injury. Overall, males (77% vs 33%) tend to present with the highest percentage of traumatic laryngeal injuries, [10] likely secondary to greater participation in violent sports and other activities such as fighting. [16]

The aforementioned study by Sethi et al found that 85.5% of the emergency room visits between 2009 and 2011 for laryngeal fracture involved males. [13]

Age

A retrospective study by McCormick et al indicated that among pediatric patients, laryngotracheal trauma occurs more often in older children. Out of 106 pediatric admissions for fractures or open wounds of the larynx and trachea, the mean patient age was 15.9 years, with 79% of the patients being male. The injuries were associated with a mean hospital stay of 8.4 days. [17]

Etiology

Laryngeal fractures can be categorized as either penetrating or blunt injuries, which can be further categorized as either high or low velocity. [18] Most commonly, trauma to the larynx occurs as a result of a motor vehicle accident (MVA) or clothesline injury. A small percentage of causes include direct blows sustained during assaults, sport injuries, hanging, manual strangulation, and iatrogenic causes. [19, 20, 21, 22]

Pathophysiology

The mechanism of injury reflects the causative agent. Inherent in any injury resulting in a laryngeal fracture is the possibility of skeletal disruption, specifically, cricothyroid and cricoarytenoid dislocations.

Laryngeal fractures from MVAs may occur in an unrestrained passenger when the extended neck impacts the steering wheel or dashboard during rapid deceleration. The anterior force compresses the larynx against the cervical vertebrae, resulting in injury.

Clothesline injuries occur when an individual in motion strikes a stationary object. The result is a crush injury to the larynx against the cervical spine.

Manual strangulation is a low-velocity, high-amplitude injury that commonly results in multiple fractures without significant displacement of cartilage, early presentation of hematoma, or endolaryngeal mucosal tears.

Common to all traumatic mechanisms is the direct transfer of severe forces to the larynx. These forces have the potential to produce many devastating injuries, including mucosal tears, dislocations, and fractures. Edema, hematoma, cartilage necrosis, voice alteration, cord paralysis, aspiration, and airway loss may accompany these injuries.

Laryngeal injuries vary by anatomical location.

-

Supraglottis: Traumatic forces commonly produce horizontal fractures of the thyroid alae and disruption of the hyoepiglottic ligament with subsequent superior and posterior displacement of the epiglottis. Repositioning of the epiglottis may result in the creation of a false lumen anterior to the epiglottis. This lumen may tunnel into the larynx or pass anterior to the thyroid cartilage and cause cervical emphysema.

-

Glottis: Traumatic force results in cruciate fractures of the thyroid cartilage near the attachment of the true vocal cords.

-

Subglottis: Crushing forces to the cricoid cartilage cause injury to the cricothyroid joint and may result in bilateral vocal cord paralysis from recurrent laryngeal nerve damage.

-

Cricoarytenoid joint: Traumatic forces that displace the thyroid alae medially or cause compression of the larynx against the cervical vertebrae often result in cricoarytenoid dislocation. This injury generally occurs unilaterally.

-

Cricothyroid joint: Injury occurs when traumatic forces to the anterior portion of the neck cause the inferior cornu of the thyroid cartilage to be displaced posterior to the cricoid cartilage. This dislocation limits cricothyroid muscle function and therefore pitch control. Injury to the recurrent laryngeal nerve may also contribute to vocal cord paralysis.

A retrospective study by Buch et al found, among laryngeal fractures observed in 55 patients, that thyroid cartilage fractures made up the largest proportion of these injuries (82%), with cricoid cartilage fractures being the next most frequent (24%). Soft tissue abnormalities (defined here as including focal hematoma, edema with non-focal hemorrhage, and additional penetrating injuries) were seen in association with all of the cricoid fractures. Of the 22% of fractures that included multiple sites, thyroid-cricoid fractures were the most common (67%). [25]

Presentation

Suspect upper-airway injury in any patient who has signs of cervical trauma. Common presenting symptoms in patients with laryngeal trauma include hoarseness, neck pain, dyspnea, dysphonia, aphonia, dysphasia, odynophonia, and odynophagia; however, no single symptom correlates well with the severity of laryngeal injury.

A thorough physical examination is vital to the appropriate management of laryngeal injury. Before progressing to other areas of physical examination, the cervical spine must first be cleared of injury. Common signs of laryngeal injury include stridor, subcutaneous emphysema, hemoptysis, hematoma, ecchymosis, laryngeal tenderness, vocal cord immobility, loss of anatomical landmarks, and bony crepitus. Suspect an acute fracture if tenderness is present upon palpation of the larynx. Assess for supraglottic airway obstruction if inspiratory stridor is present and lower airway injury if expiratory stridor is evident. Further examination of the glottis is necessary if a combination of inspiratory and expiratory stridor is present. [26]

Indications

After completing a thorough clinical examination and review of radiologic studies, laryngeal damage can be staged as described below. This classification system can then be used to direct management of the patient and to predict morbidity and mortality.

Management of Laryngeal Trauma

Table. (Open Table in a new window)

Group |

Symptoms |

Signs |

Management |

Group 1 |

Minor airway symptoms |

Minor hematomas Small Lacerations No detectable fractures |

Observation Humidified air Head of bed elevation |

Group 2 |

Airway compromise |

Edema/hematoma Minor mucosal disruption No cartilage exposure |

Direct laryngoscopy Esophagoscopy |

Group 3 |

Airway compromise |

Massive edema Mucosal tears Exposed cartilage Vocal cord immobility |

Tracheostomy Direct laryngoscopy Esophagoscopy Exploration/repair No stent necessary |

Group 4 |

Airway compromise |

Massive edema Mucosal tears Exposed cartilage Vocal cord immobility |

Tracheostomy Direct laryngoscopy Esophagoscopy Exploration/repair Stent required |

Relevant Anatomy

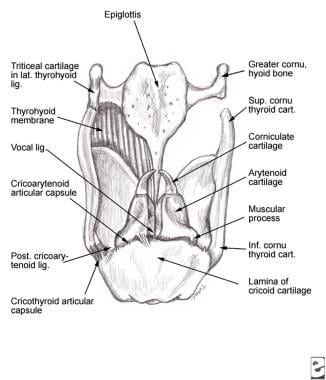

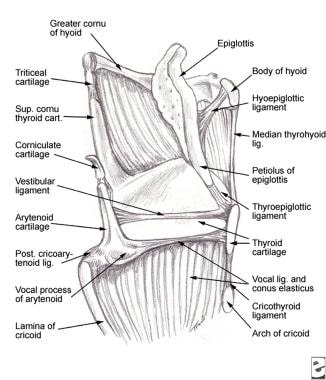

Collectively, the hyoid bone, the thyroid and cricoid cartilages, and the cricothyroid and thyrohyoid membranes form the laryngeal architecture. The arytenoid, corniculate, and cuneiform cartilages also contribute to the laryngeal structure. Membranes, ligaments, and muscles connect the entire framework. The images below represent the relevant anatomy of the laryngeal structures.

The thyroid cartilage is the largest cartilage of the larynx. The shieldlike shape of this cartilage provides protection to the internal components of the larynx. Its 2 quadrilateral plates (right and left lamina) meet to form the laryngeal prominence (Adam's apple). The superior portion of this protuberance forms the superior thyroid notch. Inferiorly, the laryngeal prominence forms the inferior thyroid notch.

Superior and inferior cornua project from the posterior margin of each side. The lower cornu articulates with the lateral edges of the cricoid cartilage and forms the cricothyroid joint. The thyrohyoid ligament connects the upper thyroid cornu to the greater cornu of the hyoid bone. The thyrohyoid membrane extends between the hyoid bone and the upper surface of the thyroid cartilage. The cricothyroid membrane extends between the thyroid and cricoid cartilages. The oblique line, the attachment site for the sternothyroid, thyrohyoid, and inferior pharyngeal constrictor muscles, is located on the outer surface of the thyroid cartilage.

Like the thyroid cartilage, the cricoid cartilage also protects the internal laryngeal structures. The cricoid cartilage is the only true supporting structure of the laryngeal skeleton and is shaped like a signet ring. Anteriorly, this cartilage forms a relatively narrow band, while posteriorly it forms a larger lamina that is approximately 2-3 cm high. The cricothyroid articulation occurs at each junction of the lamina and arch. The inferior horn of the thyroid cartilage articulates with each side of the cricoid cartilage.

The hyoid bone provides additional support to the larynx. The membrane attached to the hyoid bone elevates the larynx to prevent aspiration. The anterior body and the 2 greater cornua are directed posteriorly, and the 2 lesser cornua project superiorly.

The epiglottis is a flexible, leaflike, elastic, cartilaginous structure that tapers inferiorly to become a stalklike extension called the petiole. The petiole is the attachment site for the thyroepiglottic ligament, which connects the epiglottis to the laryngeal prominence. The superior part of the epiglottis is located posterior to the tongue and anterior to the laryngeal aditus and is not protected by the thyroid cartilage. Laterally, the aryepiglottic folds attach the epiglottis to the arytenoid cartilage. The hyoepiglottic and thyroepiglottic ligaments help stabilize the epiglottic cartilage.

The paired arytenoid cartilages are located on the superior-posterior border of the cricoid cartilage lamina. The triangular base of each arytenoid cartilage has 3 surfaces (posterior, anterolateral, medial) for the attachment of muscles and ligaments. The transverse arytenoid muscle attaches to the posterior surface. The vestibular ligament and the thyroarytenoid and vocalis muscles attach to the anterolateral surface. The medial surface contains laryngeal mucous glands. The base of each arytenoid also has a posterolateral muscular process (to which the posterior and lateral cricoarytenoid muscles attach) and an anterior caudal vocal process (to which the vocal ligaments attach). A cricoarytenoid joint is situated at the base of each arytenoid cartilage.

The corniculate cartilages (of Santorini) are located superior to the arytenoid cartilages. The cuneiform cartilages (of Wrisberg) are located lateral and superior to the corniculate cartilages. The triticeous cartilage is located in the thyrohyoid ligament.

The quadrangular membrane is elastic tissue that forms the intrinsic ligaments of the larynx—one of which is the vocal ligament. The quadrangular membrane attaches posteriorly to the upper arytenoid and corniculate cartilages. It then travels across the upper larynx to the lateral margin of the epiglottis. The lower margin of this membrane is the ventricular ligament, and the superior margin supports the aryepiglottic fold.

The conus elasticus (cricothyroid membrane) bridges the space between the cricoid and thyroid cartilages. Posteriorly, the conus elasticus attaches to the arytenoid cartilage and vocal process on each side. The vocal processes project outward to form the vocal ligaments, which join anteriorly to form the anterior commissure. The ventricular ligaments attach to the superior part of the arytenoid cartilage and then across the larynx to attach to the thyroid cartilage just superior to the vocal ligaments. The ventricular ligament forms the lower free margin of the quadrangular membrane and also forms part of the plica ventricularis.

The boundaries of the laryngeal aditus include the epiglottis anteriorly, the corniculate cartilages posteriorly, and the aryepiglottic folds laterally. The inferior border of the larynx is the cricoid cartilage. The larynx is divided into the supraglottis (vestibule), glottis (ventricle), and subglottis regions.

The supraglottis extends from the laryngeal inlet to the vestibular folds. The vestibular folds (ie, false vocal cords, superior vocal cords) are attached anterior to the thyroid cartilage just inferior to the attachment site for the epiglottis. Posteriorly, the folds attach to the arytenoid cartilages. The ventricle of the larynx (ventricle of Morgagni) is the space between the vestibular and true vocal folds. The anterior segment of this ventricle extends into a diverticulum known as the laryngeal saccule or appendix of the laryngeal ventricle. The true vocal cords are located inferior to the ventricle.

The area between the true vocal cords is known as the glottis. The glottis is considered to be the narrowest portion of the larynx. The glottic slit (rima glottidis) is the slit that separates the true vocal cords from the arytenoid cartilages. The subglottic area extends from the glottis to the cricoid cartilage. The conus elasticus forms the lateral boundary of the subglottis.

The true vocal cord consists mainly of the thyroarytenoid muscle. The thyroarytenoid muscles connect the arytenoid cartilage to the inner aspect of the thyroid cartilage. The medial and lateral bellies of each muscle parallel each other. The medial belly is called the vocalis muscle, and the lateral belly extends superiorly and inserts in the thyroid cartilage.

The cricoarytenoid muscles are important for proper laryngeal function. The lateral cricoarytenoid muscle stretches from the muscular process of the arytenoid to the upper lateral cricoid cartilage. The posterior cricoarytenoid muscle stretches from the muscular process of the arytenoid to the posterior portion of the cricoid. This muscle is the only muscle that can abduct the vocal cords. The interarytenoid muscles attach one arytenoid to the other. The lateral cricoarytenoid and the interarytenoid muscles mediate adduction of the vocal cords. The interarytenoid muscles are the only laryngeal muscles to have bilateral innervation from the recurrent laryngeal nerves. Recurrent laryngeal nerves innervate all of the other intrinsic muscles. The cricothyroid muscle is the only extrinsic laryngeal muscle innervated by the external branch of the superior laryngeal nerve (a branch of cranial nerve X). This muscle originates from the lower thyroid cartilage and attaches to the cricoid cartilage.

Innervation and blood supply

The vagus nerve provides the primary sensory innervation to the larynx. The internal laryngeal branch of the superior laryngeal nerve (of the vagus nerve) provides sensory innervation above the vocal cords, including the taste buds. The recurrent laryngeal nerve provides sensory innervation below the vocal cords. All of the intrinsic laryngeal muscles are innervated by the recurrent laryngeal nerve, and the extrinsic muscles (cricothyroideus) are innervated by the external branch of the superior laryngeal nerve.

The blood supply to the larynx parallels the nerves and consists primarily of the superior laryngeal artery (branch of the superior thyroid artery) and the inferior laryngeal branch of the inferior thyroid artery. The cricothyroid branch of the superior thyroid artery also supplies the larynx. The inferior laryngeal artery, a branch of the inferior thyroid artery, accompanies the recurrent laryngeal nerve to the larynx. The superior and inferior laryngeal veins supply venous drainage from the larynx. These veins are branches of the superior and inferior thyroid veins, respectively.

-

Thyroid fracture.

-

Hematoma of the false vocal fold.

-

Stent placement.

-

Posterior view of the laryngeal cartilages and ligaments.

-

Sagittal view of the laryngeal cartilages and ligaments.

-

Management protocol for laryngeal trauma.

-

Fractured thyroid cartilage closed with wires.

-

Laceration repair.

-

Various methods for laryngeal cartilage stabilization.