Practice Essentials

The frontal sinus (FS) is extremely resilient to injury. However, high-velocity impacts, such as motor vehicle accidents and assaults, can result in FS fractures. The potential for intracranial injuries, aesthetic deformities, and late mucocele formation is high. Thin-cut axial and coronal computed tomography (CT) scans (1.5 mm) are the criterion standards for the evaluation of FS fractures. The treatment goals are an accurate diagnosis, avoidance of short- and long-term complications, return of normal sinus function, and reestablishment of the premorbid facial contour. The treating physician must have a concise algorithm for the diagnosis and treatment of these injuries. [1, 2]

See the image below.

Workup in frontal sinus fractures

Palpate the nasal bones for crepitus and comminution. Evaluate the integrity of the medial canthal tendon (MCT) by placing the thumb and index finger over the nasal root and carefully applying lateral tension to each lower lid. Normally, a defined end point to the maneuver is evident without palpable motion at the medial orbital rim. A lax MCT or medial orbital wall motion is consistent with a nasoorbitoethmoid (NOE) complex fracture.

With regard to CT scans, axial images reveal the location, severity, and degree of comminution of anterior and posterior table fractures, while coronal images reveal fractures of the FS floor and orbital roof. The beta-2 transferrin test is the definitive means of evaluation for cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) rhinorrhea, a sign of an NOE fracture.

Management of frontal sinus fractures

Treatment options for FS fractures include observation, open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF), sinus obliteration, sinus exenteration (ie, removal of anterior table, Reidel procedure), and sinus cranialization. Options according to the type of fracture include the following:

-

Nasofrontal recess (NFR) fractures - Displaced fractures usually require FS obliteration

-

Anterior table fractures - Nondisplaced fractures can generally be managed nonoperatively; displaced fractures greater than 1-2 mm have an increased risk of aesthetic deformity and mucocele formation, and ORIF of the fracture is indicated within 7-10 days

-

Posterior table fractures - In nondisplaced fractures, treatment can involve observation (if CSF leak is absent) or FS obliteration (if CSF leak is persistent), while in displaced fractures, sinus obliteration or cranialization may be employed.

Epidemiology

Frequency

Frontal sinus (FS) fractures account for 5-12% of all facial fractures. A multicenter study from Italy, by Salzano et al, suggested that the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic significantly affected the epidemiology and etiology of facial traumas. With regard to fracture sites, the prevalence of FS fractures between February 23 and May 23, 2019 and 2020 was 0.9% and 4.4%, respectively. [3]

Etiology

Motor vehicle accidents account for 71% of frontal sinus (FS) fractures, assaults account for 10%, industrial accidents account for 5%, recreational accidents account for 4%, and other causes (eg, gunshot) account for 6%.

In a retrospective study of pediatric facial fractures seen at an urban level 1 trauma center, Oleck et al reported that frontal sinus fractures were more frequently the product of falls than of other causes of injury. [4]

Pathophysiology

Isolated anterior table fractures account for 33-39% of frontal sinus (FS) fractures. Combined fractures of the anterior table, posterior table, and/or nasofrontal recess (NFR), also termed the nasofrontal outflow tract, appear in 55-67% of cases. Isolated posterior table injuries are rare (< 6%), but the status of the displacement of the fractures and the patency of the nasofrontal recess must still be accessed. [5]

As many as 33% of patients have an associated cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leak.

Presentation

Patients with frontal sinus (FS) fractures often have associated facial injuries or panfacial fractures. A thorough head and neck examination is imperative.

-

Symptoms of FS fractures include the following:

Forehead swelling

Forehead and nasal pain

Forehead paraesthesias

-

Signs of nasoorbitoethmoid (NOE) fractures include the following:

Forehead lacerations

Forehead tenderness

Concave frontal bone contour

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) rhinorrhea (see Lab Studies)

-

Perform an initial evaluation, as follows:

Assess airway, breathing, and circulation (ABCs).

Diagnose any associated injuries.

After the patient is stabilized, perform a thorough head and neck examination to evaluate injuries to the brain, spine, and orbits.

Serious injuries are associated with FS fractures in 75% of patients. Associated facial fractures are present in 66% of patients, initial loss of consciousness occurs in 76% of patients, and prolonged periods of unconsciousness occur in 23% of patients.

A team approach involving the otolaryngologist or plastic surgeon, neurosurgeon, and ophthalmologist is recommended. Consultation with an ophthalmologist is mandatory.

-

Conduct directed examination of the FS, as follows:

Displaced fractures of the anterior table without overlying lacerations may not be apparent on physical examination because of soft tissue swelling or hematoma.

All forehead lacerations should be examined under sterile conditions to assess the integrity of the anterior table, posterior table, and dura.

Clean and examine the nasal cavity for the presence of a CSF leak. Query all conscious patients about the presence of watery rhinorrhea or salty postnasal drainage.

Palpate the nasal bones for crepitus and comminution.

Evaluate the integrity of the medial canthal tendon (MCT) by placing the thumb and index finger over the nasal root and carefully applying lateral tension to each lower lid. Normally, a defined end point to the maneuver is evident without palpable motion at the medial orbital rim. A lax MCT or medial orbital wall motion is consistent with an NOE complex fracture.

Relevant Anatomy

Development

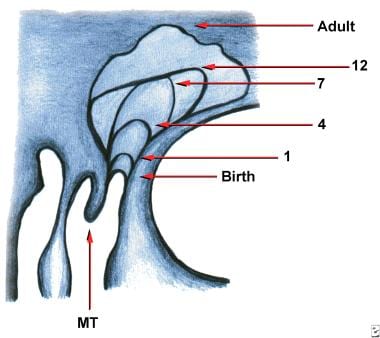

The frontal sinus (FS) is absent at birth. The anterior ethmoid cells invade the frontal bone at 2 years of age, and the FS attains adult size at approximately 15 years of age. The image below is a diagram of frontal sinus development.

The FS measures 30 mm tall, 25 mm wide, and 19 mm deep in the average adult, demonstrated in the image below. Average FS volume is 10 cm3.

Anterior and lateral views of the frontal sinus. These figures demonstrate the relative thickness of the anterior and posterior tables, as well as the relationship of the frontal sinus to the orbits, ethmoid sinuses, and anterior cranial fossa.

Anterior and lateral views of the frontal sinus. These figures demonstrate the relative thickness of the anterior and posterior tables, as well as the relationship of the frontal sinus to the orbits, ethmoid sinuses, and anterior cranial fossa.

The FS is most commonly bilateral, asymmetric, and pyramidal in shape.

-

The pyramidal base is located inferiorly, and the apex is located superiorly. The floor of the sinus forms the medial portion of the orbital roof.

-

The FS usually is divided by one or more intersinus separations. A unilateral, rudimentary, or absent FS is present in 20% of individuals.

Anterior table

The anterior table forms part of the forehead, brow, and glabella. It averages 4 mm in thickness but can be as thick as 12 mm. The anterior table is more resistant to fracture than any other facial bone.

Posterior table

The posterior table abuts the anterior cranial fossa. The thickness of the posterior table ranges from 0.1-4.8 mm, and it is much less resistant to injury than the anterior table.

Frontal sinus ostia

The FS has 2 ostia located on the posterior inferior aspect of the sinus floor. They are positioned anterior to the anterior ethmoid air cells, medial to the orbit, lateral to the intersinus septum, and posterior to the frontal bone.

Each ostium is approximately 3-4 mm in diameter and represents the sole drainage site for the FS.

The true ostium is the narrowest point of an hourglass configuration. The FS infundibulum is located cephalad to the ostia (the upper part of the hourglass) and narrows down to the true ostia. The NFR widens out below the ostia (the lower part of the hourglass) and enters into the ethmoid infundibulum.

The NFR is extremely short in 85% of individuals and, thus, is more accurately described as a recess rather than a true duct.

Neurovascular supply

The supraorbital and supratrochlear vessels provide arterial supply to the FS. Venous drainage occurs through 3 pathways: the facial vein, the ophthalmic vein/cavernous sinus, and the foramina of Breschet/subarachnoid space.

Sensory innervation of the FS comes from the ophthalmic branch of the trigeminal nerve.

-

Diagram of frontal sinus development.

-

Anterior and lateral views of the frontal sinus. These figures demonstrate the relative thickness of the anterior and posterior tables, as well as the relationship of the frontal sinus to the orbits, ethmoid sinuses, and anterior cranial fossa.

-

The fascial planes of the forehead and temple. The temporal branch of the facial nerve runs within the superficial temporal fascia (ie, temporoparietal fascia).

-

The compressive force of frontal bone as the bone is deformed from a convex shape to a concave shape.

-

Intraoperative photograph of a single miniscrew (located between miniplates) placed in the anterior table bone to reduce/stabilize the fracture fragments while rigid fixation was applied.

-

A frontal sinus template can be cut from blank radiographic film and sterilized for intraoperative localization of the front sinus. Note the lateral wings paralleling the orbital rims, which help to correctly orient the template over the sinus.

-

Sagittal CT scan demonstrating frontal sinus floor depressed fracture obstructing nasofrontal outflow tract.