History of the Procedure

Mandible fractures are described in early Egyptian writings. Hippocrates advocated the use of bandages and interdental wiring for the treatment of mandibular fractures. In a 3-part article published during the Civil War, Gunning wrote of using dental splints attached to elaborate external appliances. In 1881, Gilmer first described the use of bars on both arches, fixed to the teeth and to each other with fine wire ligatures. [1]

The first mandibular bone plating is credited to Schede, who is said to have used a steel plate screwed to the mandible in the late 1880s. In 1934, Vorschutz described external fixation using transdermal bone screws and plaster. The Morris biphase is a refinement of that technique.

History of rigid internal fixation devices is ongoing, with a new theory and a corresponding set of devices appearing every few years. [2, 3, 4, 5, 6]

Problem

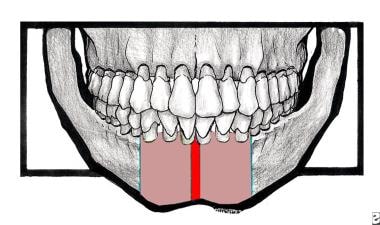

Fractures that occur in the midline of the mandible are classified as symphyseal. When teeth are present, the fracture line passes between the mandibular central incisors. Fractures occurring in the area of the mandible from cuspid to cuspid, but not in the midline, are classified as parasymphyseal (as seen in the image below). The treatment of these types of fractures differs little, if at all; therefore, they are discussed together.

Epidemiology

Frequency

In the United States, the incidence of facial fractures of the mandible is second only to that of the nose. Fractures of the symphysis/parasymphysis region account for approximately 10% of mandibular fractures, which makes this the fourth most common region to be fractured. [7]

A study by Morris et al found the proportion of various types of mandibular fractures (4143 fractures; 2828 patients) to be as follows [8] :

-

Angle (27%)

-

Symphysis (21.3%)

-

Condyle and subcondyle (18.4%)

-

Body (16.8%)

A study by Jung et al of 1172 mandibular fractures (735 patients) found the symphysis to be the most frequent fracture site, accounting for 431 fractures (36.8%). [9]

The major difference in mandible fractures in countries other than the United States concerns etiology of fractures. [10] In some locations, vehicular trauma is a lesser cause because of a relative lack of vehicular transportation. Interpersonal facial trauma tends to be of lower energy than vehicular trauma, thus resulting in generally less severe injuries. Most countries other than the United States have fewer incidents with civilian firearms and a correspondingly lower incidence of penetrating trauma.

Etiology

The etiology of symphyseal and parasymphyseal fractures is largely from trauma from interpersonal violence or motor vehicle accidents. Falls, industrial accidents, and sports injuries are lesser etiologies. Most trauma is blunt, but penetrating trauma is common with interpersonal violence and war injury.

Pathophysiology

Blunt trauma can injure any part of the mandible. A sharp blow applied anteriorly often fractures the symphyseal/parasymphyseal region and the condyle region or regions. Blunt force applied broadly across the body of the mandible may also result in a fracture of the symphyseal/parasymphyseal region.

Presentation

The patient has a history of trauma. Pain and tenderness are present about the anterior mandible, and the patient reports malocclusion. False motion of the mandible is usually evident.

Preoperative examinations are often impaired by tenderness and masticatory muscle spasm; therefore, a thorough reexamination of the face and oral cavity is performed prior to definitive therapy. The entire mandible is carefully inspected and palpated. All teeth are inspected and evaluated for injury and mobility. A survey of the dental arches is completed to detect any sockets missing teeth. The maxilla is examined to detect any previously missed injuries.

Indications

Presence of a symphyseal/parasymphyseal fracture is the indication for treatment. Mode of treatment varies among patients.

Relevant Anatomy

Fractures of the symphysis/parasymphysis are inherently unstable. Muscles of mastication insert into posterior portions of the mandible with a net effect of superior rotation about the axis of the temporomandibular joint. The suprahyoid muscles of the neck act directly on the anterior mandible, with a net effect of inferior rotation around the axis of the temporomandibular joint and scissoring motion around a vertical axis through the symphysis. The later action is from the mylohyoid muscles.

Fractures of the anterior mandible lack 2 of the stabilizing factors provided to fractures of the posterior tooth-bearing mandible: the splinting effects of the masseter and internal pterygoid muscles, which form a natural sling, and the interlocking cusps and fossae of bicuspid and molar teeth.

Contraindications

The only absolute contraindication to managing these fractures exists if the patient is not stable enough to undergo the needed treatment. A specific contraindication for maxillomandibular fixation (MMF) is poorly controlled seizures. Patients with uncleared cervical spines present limitations regarding which treatment for facial fractures is safe.

-

The broad red line indicates the symphyseal area. The pink area between the cuspid teeth, excepting the symphysis, indicates the parasymphyseal area.

-

The model on the left shows comminuted fractures. The model on the right has been repaired to facilitate preoperative contouring of a reconstruction plate.

-

Opposing lag screws have been used to treat a symphyseal fracture. This procedure requires precise technique and is not for the occasional operator.

-

Two miniplates are required for the symphysis/parasymphysis region because it is subjected to torsional forces, which would be poorly resisted by one miniplate.

-

Tension banding is required to prevent splaying of the fracture line at the superior surface of the mandible when using a dynamic compression plate. A mandibular arch bar can accomplish this. In this example, a miniplate is used.