Sleep-Disordered Breathing

Snoring, excessive daytime somnolence, restless sleep, and apnea are manifestations of sleep-disordered breathing. Understanding of the pathophysiology related to these problems has led to some successes in nonsurgical and surgical interventions.

Numerous sleep disorders are organized in the International Classification of Sleep Disorders by the American Sleep Disorders Association. The primary disorders that may warrant surgical intervention include snoring and obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). The surgical management of OSA is discussed below.

Apnea is obstructive only when polysomnography reveals a continued inspiratory effort, evidenced by abdominal and thoracic muscle contraction. [1] In central apnea, absence of airflow accompanies a lack of inspiratory effort, and this condition is not amenable to surgical correction. At times, apnea may be mixed, occurring with obstructive and central apnea symptoms. Patients with this condition present a therapeutic challenge to the surgeon.

Go to Obstructive Sleep Apnea for more complete information on this topic.

Associated morbidity

Snoring is an undesirable sound that originates from the soft tissues of the upper airway during sleep. It is usually a source of contention for patients and their bed or dwelling partners, and it may be a harbinger of something more serious, such as OSA.

OSA is a sleep disorder in which airflow is repeatedly reduced or ceased. The disorder may vary in severity and is often associated with other physiologic problems. These problems include, among others, the following:

-

Altered mood and behavior (depression, lethargy, cognitive and memory impairment)

-

Morning headaches

-

Decreased libido

-

Systemic and pulmonary hypertension

-

Congestive heart failure

-

Sleep-related arrhythmias

Regarding the third item above, a study by Budweiser et al demonstrated an independent correlate between obstructive sleep apnea and erectile dysfunction. [2]

Studies have demonstrated that an apnea index of 20 or more, even in asymptomatic patients, is associated with an increased mortality rate. The author spends a significant amount of time educating patients about treatment options and the risks of untreated OSA (eg, hypertension, stroke, cardiovascular disease). [3] As an indication of the link between OSA and cardiovascular disease, a study by Jung et al reported that the severity of OSA, as measured via the respiratory disturbance index, the Epworth Sleepiness Scale, and least oxygen saturation, significantly correlates with C-reactive protein levels. [4]

Surgical management

Many surgical procedures for OSA are available, but uvulopalatopharyngoplasty (UPPP, or UP3) is the most frequently performed operation. Further investigation into the pathophysiology of OSA and the long-term efficacy of current surgical therapy is indicated and ongoing. (See Surgical Treatment of OSA.)

Indications for Surgery

Surgical management of snoring and OSA is indicated when a surgically correctable abnormality is believed to be the source of the problem and the patient has tried continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) without success. In addition, many patients opt for surgical treatment after noninvasive forms of treatment have proven ineffective or difficult to tolerate.

Surgical alteration of the upper airway usually involves 1 or more structures, such as the nasal septum, inferior nasal turbinates, adenoids, tonsils, anterior and posterior tonsillar pillars, uvula, soft palate, and base of the tongue. Craniofacial abnormalities, whether acquired or congenital, may also be amenable to surgical correction. In unusual cases, obstruction may occur at the level of the larynx (eg, tumor, laryngomalacia).

Contraindications to Surgery

Palatal surgery is contraindicated in patients with velopharyngeal insufficiency or a submucous cleft palate. Medical conditions that preclude the use of a general anesthetic are a relative contraindication to surgery.

Cephalometric Radiography

The value of cephalometric radiography (plain radiography of the airways) in routine presurgical workup is highly debated. The study is most useful in assessing craniofacial skeletal abnormalities. Lateral airway images can be helpful in diagnosing adenoid hypertrophy in young pediatric patients.

CT Scanning and MRI

Computed tomography (CT) scanning and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are rarely performed in the workup for OSA, because they do little to guide therapeutic intervention, are expensive, and expose patients to unnecessary radiation.

Surgical Treatment of OSA

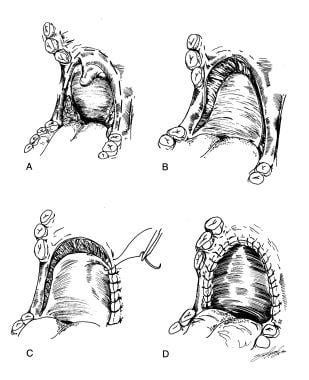

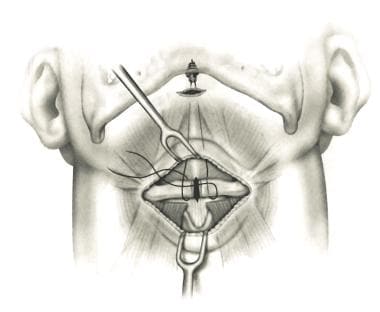

When surgical therapy is indicated, conservative procedures are attempted first. These procedures include uvulectomy, nasal reconstruction, adenotonsillectomy, and palatal implants. More aggressive operations include uvulopalatopharyngoplasty (UPPP, or UP3; demonstrated in the image below) and genioglossal advancement with hyoid myotomy. Second-line treatments for OSA are more complex and include maxillary-mandibular advancement, bimaxillary advancement, palatal advancement and tongue-base surgery (midline glossectomy), and tracheostomy.

Uvulopalatopharyngoplasty. Reprinted with permission from Elsevier [Hester JE, Powell NB, Riley RW, and Li KK. Maxillary-mandibular advancement in obstructive sleep apnea. Operative Techniques in Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2002;13(2):135-7].

Uvulopalatopharyngoplasty. Reprinted with permission from Elsevier [Hester JE, Powell NB, Riley RW, and Li KK. Maxillary-mandibular advancement in obstructive sleep apnea. Operative Techniques in Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2002;13(2):135-7].

Uvulectomy

A patient with a large uvula who snores and has few or no symptoms of apnea may benefit from uvulectomy. The patient can be given local anesthesia, and uvulectomy can be performed as an office procedure by using cautery or a carbon dioxide laser. In 1993, laser-assisted uvulopalatoplasty was first described as a procedure for individuals with mild OSA who snore. The procedure consists of incising the inferior rim of the soft palate and uvula. The tonsils are not removed.

Pillar system

The Pillar procedure, involving the insertion of palatal implants, is a minimally invasive operation used to treat people with habitual snoring and those with mild to moderate OSA. The Pillar procedure addresses the soft palate, which is one of the anatomic components of sleep apnea and snoring.

During the Pillar procedure, 3 tiny, woven inserts are placed in the soft palate to help reduce the vibration that causes snoring and the ability of the soft palate to obstruct the airway. Once in place, the inserts add structural support to the soft palate. Over time, the body's natural tissue response to the inserts increases the structural integrity of the soft palate. This procedure can be performed in the office or in the operating room as an adjunctive procedure.

A study performed in Norway indicated that the procedure is relatively successful (70%) in terms of bed-partner satisfaction. [5] The cure rate depends on the severity of the preoperative sleep apnea. In most cases, the author encourages patients to undergo an overnight sleep study to assess the severity of the sleep-disordered breathing.

Nasal reconstruction

Relief of nasal obstruction alone rarely cures OSA; however, patient tolerance and response to nasal CPAP are often improved. Septoplasty, septorhinoplasty, and turbinate reduction may be indicated in patients who have a predisposed anatomy.

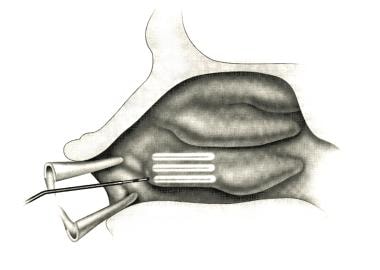

Turbinates can be reduced in a number of different ways, including through traditional total or partial turbinectomies, submucous resection, cryotherapy, laser vaporization, bipolar radiofrequency coblation, and radiofrequency ablation. The author has found the lateral crural J-flap procedure to be useful in patients with external nasal valve collapse who have had trouble tolerating CPAP with the nasal pillows mask. [6] Radiofrequency turbinate ablation is demonstrated below.

Bipolar radiofrequency cold ablation turbinate reduction for obstructive inferior turbinate hypertrophy. Depiction of linear passage of the coblation wand. Reprinted with permission from Elsevier [Bhattacharyya N and Kepnes LJ. Bipolar radiofrequency cold ablation turbinate reduction for obstructive inferior turbinate hypertrophy. Operative Techniques in Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2002;13(2):170-4].

Bipolar radiofrequency cold ablation turbinate reduction for obstructive inferior turbinate hypertrophy. Depiction of linear passage of the coblation wand. Reprinted with permission from Elsevier [Bhattacharyya N and Kepnes LJ. Bipolar radiofrequency cold ablation turbinate reduction for obstructive inferior turbinate hypertrophy. Operative Techniques in Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2002;13(2):170-4].

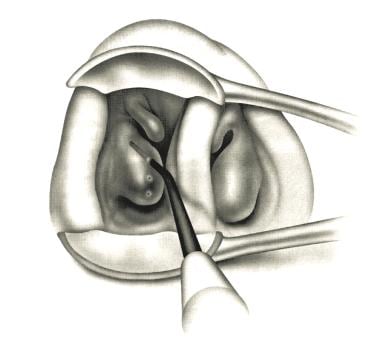

Bipolar radiofrequency cold ablation turbinate reduction for obstructive inferior turbinate hypertrophy. Anterior rhinoscopic view of the coblation wand as it enters the anterior head of the right inferior turbinate. Reprinted with permission from Elsevier [Bhattacharyya N and Kepnes LJ. Bipolar radiofrequency cold ablation turbinate reduction for obstructive inferior turbinate hypertrophy. Operative Techniques in Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2002;13(2):170-4].

Bipolar radiofrequency cold ablation turbinate reduction for obstructive inferior turbinate hypertrophy. Anterior rhinoscopic view of the coblation wand as it enters the anterior head of the right inferior turbinate. Reprinted with permission from Elsevier [Bhattacharyya N and Kepnes LJ. Bipolar radiofrequency cold ablation turbinate reduction for obstructive inferior turbinate hypertrophy. Operative Techniques in Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2002;13(2):170-4].

Adenotonsillectomy

Adenotonsillectomy is often performed in the pediatric population to correct loud snoring and restless sleep. OSA is the primary indication for tonsillectomy in the pediatric population. [7, 8]

The tonsils and adenoids can be removed or reduced in a number of ways. The surgeon’s preference, the cost of the procedures, and postoperative pain and complications dictate which methods are used in each institution. The choice of which procedures are employed is subject to change over time.

The methods can utilize standard cautery, snare, bipolar cautery, harmonic scalpel, coblation, temperature-controlled radiofrequency, or microdebrider-powered shavers. In children, palatal surgery is usually necessary only in cases of extreme obesity.

A randomized, controlled study by Garetz et al of 453 children with OSA found significantly greater improvement in quality-of-life and symptom severity measurements in those who underwent adenotonsillectomy than in children who were treated with watchful waiting with supportive care. [9]

A study by Kuo et al indicated that in children undergoing adenotonsillectomy for OSA, nonobese children experience a greater improvement in postoperative blood pressure than do obese children. In contrast to obese children in the study (39 patients), the nonobese children (39 patients) showed significant improvement in nocturnal and morning diastolic blood pressure and in the diastolic blood pressure index. [10]

Palatal surgery

UPPP is the most common procedure for the treatment of OSA syndrome. This procedure, introduced by Fujita in 1981, consists of tonsillectomy, reorientation of the anterior and posterior tonsillar pillars, and excision of the uvula and posterior rim of the soft palate. For patients without tonsils and an enlarged tongue base, Friedman advocated a Z-palatoplasty.

Transpalatal advancement pharyngoplasty has also been described and includes the removal of a portion of the posterior hard palate and anterior suspension of the soft palate. This procedure has evolved because of the unpredictable success of UPPP, but it is not widely performed in the United States.

Genioglossal advancement

Genioglossal advancement involves performing a mandibular osteotomy with anterior repositioning of the genioglossus-attached segment of the mandible. This procedure results in anterior displacement of the tongue.

Thyrohyoid suspension

Friedman designed thyrohyoid suspension (see the images below) for patients with moderate to severe OSA without enlarged palatine tonsils or for patients with a short (< 40 mm) hyomental distance. This procedure involves making a horizontal incision in the midline of the neck and advancing the hyoid bone anteriorly and inferiorly to the thyroid cartilage.

Hyoid suspension for obstructive sleep apnea. The hyoid is divided in the midline, and the loop suture is passed around the hyoid. The loop suture is suspended to the mandible, thereby suspending the tongue base anterosuperiorly. This enhances the posterior air space. A variation of this procedure is the hyoid advancement, whereby the hyoid is advanced, with several sutures (ie, 2-0 Ethibond) anteriorly and inferiorly over the thyroid lamina. Reprinted with permission from Elsevier [Krespi YP and Kacker A. Hyoid suspension for obstructive sleep apnea. Operative Techniques in Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2002;13(2):144-9].

Hyoid suspension for obstructive sleep apnea. The hyoid is divided in the midline, and the loop suture is passed around the hyoid. The loop suture is suspended to the mandible, thereby suspending the tongue base anterosuperiorly. This enhances the posterior air space. A variation of this procedure is the hyoid advancement, whereby the hyoid is advanced, with several sutures (ie, 2-0 Ethibond) anteriorly and inferiorly over the thyroid lamina. Reprinted with permission from Elsevier [Krespi YP and Kacker A. Hyoid suspension for obstructive sleep apnea. Operative Techniques in Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2002;13(2):144-9].

In essence, this procedure draws the base of the tongue forward, making it less likely to fall back against the posterior pharyngeal wall during sleep. In addition, the hyoid bone may be repositioned anteriorly with transection of the infrahyoid muscles and suspension to the mandible.

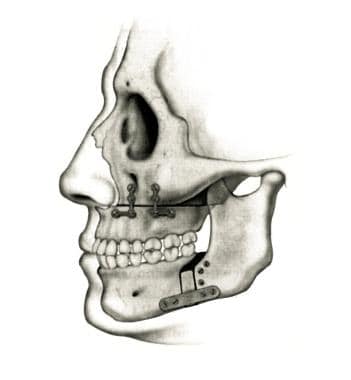

Maxillary-mandibular advancement

Maxillary-mandibular advancement is performed in an attempt to widen the airway while maintaining the existing occlusion or, optimally, to obtain class I occlusion. Outer-table cranial bone is obtained initially through a coronal incision. Arch bars are placed, and maxillary osteotomies are performed. The maxilla is advanced 8-12 mm. Mandibular osteometries are also performed, and the mandible is advanced to obtain optimal occlusion. Bone grafts are used at the osteotomy sites as needed. Intermaxillary fixation is necessary postoperatively.

A wide variety of maxillomandibular advancement techniques have been described, all with the goal of advancing skeletal support for the tongue and pharynx.

The results of maxillary-mandibular advancement are seen in the image below.

Maxillary-mandibular advancement in obstructive sleep apnea. Final appearance of the advancement with rigid fixation. Reprinted with permission from Elsevier [Hester JE, Powell NB, Riley RW, and Li KK. Maxillary-mandibular advancement in obstructive sleep apnea. Operative Techniques in Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2002;13(2):135-7].

Maxillary-mandibular advancement in obstructive sleep apnea. Final appearance of the advancement with rigid fixation. Reprinted with permission from Elsevier [Hester JE, Powell NB, Riley RW, and Li KK. Maxillary-mandibular advancement in obstructive sleep apnea. Operative Techniques in Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2002;13(2):135-7].

Tongue-base surgery

Lingual tonsillectomy, lingualplasty, and laser midline glossectomy are moderately successful procedures designed to reduce the mass of the tongue base. Proper postoperative airway support requires a temporary tracheotomy.

Radiofrequency ablation

Temperature-controlled radiofrequency tissue ablation (TCRFTA) is performed by submucosally delivering low-power electrical energy with a needle electrode. [11] This procedure has been proposed to improve airway patency with less morbidity than that of traditional surgical approaches to OSA. The surgery has been used in the tongue base and in the soft palate, and sometimes in both in the same setting. This procedure can be performed in the clinic with local anesthesia. Multiple treatments may accomplish the desired result.

Tracheotomy

Permanent tracheotomy cures OSA and is indicated most often in patients with severe apnea that is associated with life-threatening cardiac arrhythmias. Other less frequent indications may include morbid obesity, obstruction with severe hypoxia, and disabling daytime somnolence. This is not commonly used today.

Postoperative Care

Elevating the patient's bed in the recovery room and having a bilevel positive airway pressure (Bi-PAP) or CPAP device readily available is useful.

Traditionally, patients who undergo UPPP have been kept at least overnight to allow airway observation and to ensure adequate oral intake. Most serious complications seem to occur within the first 2-3 hours after surgery, and many patients (who have not undergone multilevel airway surgery) can be safely discharged home with detailed instructions. [12] Patients who are discharged the day of surgery are counseled by the author to sleep in a recliner for the first 2 nights and to try to use their CPAP device if possible. Ensuring that the patient lives relatively close to the hospital and has reliable transportation is crucial.

Follow-up assessment

After surgical procedures, polysomnography is necessary to assess the outcome. Six months is a generally accepted interval.

Postoperative Complications

Postobstructive pulmonary edema occasionally occurs after relief of clinically significant airway obstruction. This condition manifests as airway edema and respiratory distress, and it results from the dramatic alteration in pulmonary physiology that follows obstruction removal.

Complications from septoplasty include nasal bleeding, septal hematoma, injury to the skull base that results in an altered sense of smell or cerebrospinal leak, and septal perforation.

Nasal crusting and bleeding can occur after turbinoplasty, regardless of the method used to reduce the turbinates’ size. Rhinoplasty may leave the patient with an unappealing cosmetic result that may require further surgery.

The palatal Pillar system has been used for only the past few years. To date, complications include superficial mucosal ulcerations and dislodgement of the pillar implants. The complication rate seems to be about 3%, based on the studies currently available.

Minor bleeding is the only common complication of uvulopalatoplasty; UPPP may provoke more significant bleeding when the tonsils are removed. Airway obstruction, velopharyngeal insufficiency, and nasopharyngeal stenosis are less common complications of UPPP. Most advocate inpatient care in a closely monitored unit.

The most common (10-12%) complication of transpalatal advancement pharyngoplasty is an oronasal fistula, which seems to be temporary in most cases.

Tongue-base surgery is sometimes associated with bleeding, dysphagia, odynophagia, and airway edema. Superficial ulcer formation, hypoglossal nerve injury, and abscess are less common complications. Taste may also be altered after tongue-base surgery and, in rare cases, following standard tonsillectomy.

Radiofrequency ablation of the tongue base and soft palate is associated with rare, minor complications. These include mild pain, swelling, and mucosal ulceration that generally resolves unaided within 1-2 months.

Genioglossal advancement with hyoid suspension may be complicated by bleeding or infection in the floor of the mouth, Warthin duct injury, dental trauma, neck hematoma, pharyngocutaneous fistula, and wound infection.

Maxillary-mandibular advancement procedures may result in injury to the lingular neurovascular bundle. Most sensory impairments resolve over time. Cosmesis is generally not a problem.

A study by Friedman et al found a higher incidence of complications in patients with OSA who underwent multilevel surgery that included UPPP than in those who were treated with UPPP alone (4.63% vs 1.6%, respectively), although values for fatal complications were too small to compare. [13]

The complications of tracheotomy include bleeding, pneumothorax, subcutaneous emphysema, and formation of peristomal scar tissue. Early tube dislodgment can occur and may result in hypoxia and death if the tube is not promptly replaced.

Postsurgical Prognosis

Patients with mild obstructive disease are more likely to respond to surgical treatment than are those with more severe disease.

Most investigators define successful treatment of OSA as a decrease of 50% in the respiratory disturbance index (RDI) and a decrease in this number to less than 20 on postpolysomnography. Other, less objective measures include an improvement in the patient’s energy level and ability to concentrate.

The 59% surgical success rate of multilevel TCRFTA in a study by Steward was comparable with published success rates of 50% with UPPP and tongue-base TCRFTA and with published success rates of 42-59% with UPPP and midline glossectomy. [14] The published success rate with UPPP and genioglossus advancement is 35-77%, with or without hyoid myotomy and suspension. A study by de Ruiter et al found that maxillary-mandibular advancement had a 71% success rate in patients with moderate to severe OSA, with the mean apnea-hypopnea index reduced by 69%. Older age and larger neck circumference appeared to increase the risk of OSA treatment failure in this procedure. [15]

The published success rate of 90% or more with combined UPPP, genioglossus advancement, and maxillary-mandibular advancement is most impressive. [16, 17]

A study by MacKay et al indicated that in adults with moderate to severe OSA who have not responded to conventional therapy, treatment with combined palatal and tongue surgery is more effective than medical management at reducing apnea and hypopnea events and patient-reported sleepiness. Individuals in the study underwent either multilevel surgery (modified UPPP and minimally invasive tongue volume reduction) or ongoing medical management (aimed, for example, at sleep positioning and weight loss). Among the surgical patients, the apnea-hypopnea index fell from a mean 47.9 at baseline to 20.8 at 6 months, while the medical management patients saw the number drop from 45.3 at baseline to 34.5 at 6 months. Moreover, for the patients who underwent surgery, the mean Epworth Sleepiness Scale score changed from 12.4 at baseline to 5.3 at 6 months, while in the other patients the figures were 11.1 at baseline and 10.5 at 6 months. [18]

Patients at less than 125% of their ideal body weight are most likely to have short-term and long-term benefits from surgical treatment of snoring and obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). Other important variables include severity of disease, age at onset of symptoms, and comorbidities.

Outcome data from numerous studies have demonstrated significant short-term benefits from the aforementioned surgical procedures in appropriately selected patients. Additional efforts also affect the long-term results and prognosis for patients.

Questions & Answers

Overview

What is sleep-disordered breathing?

What is obstructive sleep apnea (OSA)?

What are the health risks associated with untreated obstructive sleep apnea (OSA)?

What is the most common surgical intervention used to treat obstructive sleep apnea (OSA)?

When is surgery indicated for the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA)?

When is surgery contraindicated for the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA)?

What is the role of CT and MRI in the presurgical evaluation of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA)?

What types of surgical interventions are used in the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA)?

What is the role of uvulectomy in the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA)?

What is the role of the Pillar system in the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA)?

What is the role of nasal reconstruction in the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA)?

What is the role of adenotonsillectomy in the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA)?

What is the role of palatal surgery in the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA)?

What is the role of genioglossal advancement in the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA)?

What is the role of thyrohyoid suspension in the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA)?

What is the role of tongue-base surgery in the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA)?

What is the role of radiofrequency ablation in the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA)?

What is the role of tracheotomy in the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA)?

-

Uvulopalatopharyngoplasty. Reprinted with permission from Elsevier [Hester JE, Powell NB, Riley RW, and Li KK. Maxillary-mandibular advancement in obstructive sleep apnea. Operative Techniques in Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2002;13(2):135-7].

-

Hyoid suspension for obstructive sleep apnea. The infrahyoid muscles are detached from the body of the hyoid bone using electrocautery. Reprinted with permission from Elsevier [Krespi YP and Kacker A. Hyoid suspension for obstructive sleep apnea. Operative Techniques in Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2002;13(2):144-9].

-

Hyoid suspension for obstructive sleep apnea. The hyoid is divided in the midline, and the loop suture is passed around the hyoid. The loop suture is suspended to the mandible, thereby suspending the tongue base anterosuperiorly. This enhances the posterior air space. A variation of this procedure is the hyoid advancement, whereby the hyoid is advanced, with several sutures (ie, 2-0 Ethibond) anteriorly and inferiorly over the thyroid lamina. Reprinted with permission from Elsevier [Krespi YP and Kacker A. Hyoid suspension for obstructive sleep apnea. Operative Techniques in Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2002;13(2):144-9].

-

Maxillary-mandibular advancement in obstructive sleep apnea. Final appearance of the advancement with rigid fixation. Reprinted with permission from Elsevier [Hester JE, Powell NB, Riley RW, and Li KK. Maxillary-mandibular advancement in obstructive sleep apnea. Operative Techniques in Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2002;13(2):135-7].

-

Bipolar radiofrequency cold ablation turbinate reduction for obstructive inferior turbinate hypertrophy. Depiction of linear passage of the coblation wand. Reprinted with permission from Elsevier [Bhattacharyya N and Kepnes LJ. Bipolar radiofrequency cold ablation turbinate reduction for obstructive inferior turbinate hypertrophy. Operative Techniques in Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2002;13(2):170-4].

-

Bipolar radiofrequency cold ablation turbinate reduction for obstructive inferior turbinate hypertrophy. Anterior rhinoscopic view of the coblation wand as it enters the anterior head of the right inferior turbinate. Reprinted with permission from Elsevier [Bhattacharyya N and Kepnes LJ. Bipolar radiofrequency cold ablation turbinate reduction for obstructive inferior turbinate hypertrophy. Operative Techniques in Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2002;13(2):170-4].

-

Preoperative findings: The larynx is exposed with a Parson's laryngoscope; the laryngeal inlet and supraglottic structures are visualized along with an appropriate sized laser-safe endotracheal tube. Short, tethered aryepiglottic folds are noted bilaterally.

-

Postoperative result: Successful decrease in prolapse of supraglottic structures after release of the aryepiglottic fold with evidence of excellent hemostasis.

-

Preoperative findings: The prominent lingual tonsil and underlying epiglottis are exposed with an operating laryngoscope.

-

Postoperative result: Successful interval reduction of lingual tonsillar hypertrophy using electrocautery with evidence of excellent hemostasis.