Practice Essentials

Since the late 1960s, gastroesophageal acid reflux has been implicated in the pathogenesis of several extraesophageal disorders, including laryngitis. [1] Although the cause-effect relationship has been strengthened by more recent evidence, the body of evidence on causation, diagnosis, and treatment of these increasingly diagnosed disorders is still evolving.

Barium esophagography and laryngoscopy are among the procedures used in determining the presence of reflux, with proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) being the mainstay of treatment for laryngopharyngeal reflux (LPR).

Signs and symptoms of reflux

Various symptoms, functional and structural abnormalities that involve the larynx, and other contiguous structures positioned proximal to the esophagus constitute the spectrum of these disorders. Patients presenting with extraesophageal reflux–related signs and symptoms may account for up to 10% of an otolaryngologist's practice. [2] A large amount of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD)–associated and laryngopharyngeal reflux (LPR)–associated processes are treated primarily by otolaryngologists. This list includes the following:

-

Chronic laryngitis

-

Hoarseness

-

Globus sensation

-

Chronic cough or throat clearing

-

Dysphagia

-

Halitosis

-

Chronic rhinosinusitis

-

Laryngeal malacia

-

Laryngeal stenosis

-

Laryngeal carcinoma

Various terms such as laryngopharyngeal reflux (LPR), supraesophageal GERD, atypical GERD, and extraesophageal complications of GERD have been used to describe this group of symptoms and signs. Although addressed by various terms, these basically represent supraesophageal complications due to reflux of gastric acid content through the esophageal/pharyngeal/laryngeal/pulmonary axis. Although these symptoms were previously thought to constitute the spectrum of GERD, laryngopharyngeal reflux (LPR) is today thought to be a distinct entity and should be managed differently. [3] Laryngopharyngeal reflux (LPR) is the term used in this article to discuss the pathogenesis of reflux laryngitis.

Workup

Laryngoscopy is the primary procedure for diagnosing laryngopharyngeal reflux (LPR). The more commonly used flexible laryngoscopy is more sensitive but less specific than rigid laryngoscopy in revealing laryngeal tissue irritation in suspected laryngopharyngeal reflux (LPR). [4]

Failing to recognize laryngopharyngeal reflux (LPR) is dangerous, while overdiagnosis of laryngopharyngeal reflux (LPR) can lead to unnecessary costs and missed diagnosis. Inflamed laryngeal tissue affected by laryngopharyngeal reflux (LPR) is more easily damaged from intubation, has a high risk of progressing to contact granulomas, and may evolve to symptomatic subglottic stenosis. [5]

In a report, laryngopharyngeal reflux (LPR) symptoms were found to be more prevalent in patients with esophageal adenocarcinoma than were typical GERD symptoms, and they often represented the only sign of disease. [6] On the other hand, increased awareness may lead to overdiagnosis of the condition because typical laryngopharyngeal reflux (LPR) symptoms are nonspecific and can occur in processes such as infection, vocal abuse, allergy, smoking, inhaled irritants, and alcohol abuse. [3]

Caution must also be taken to rule out serious processes that may present with similar symptoms, such as laryngeal cancer, before proceeding with conservative management.

Management

Four categories of drugs are used in treating laryngopharyngeal reflux (LPR): PPIs, [7] H2-receptor agonists, prokinetic agents, and mucosal cryoprotectants. However, PPIs are the mainstay of treatment.

The apparent advantage of operative therapy is that it corrects the antireflux barrier at the gastroesophageal junction and prevents the reflux of most stomach contents, thus preventing acid and nonacidic material from coming in contact with the pharyngolaryngeal mucosa. Candidates for antireflux surgery are often patients who require continuous or increasing doses of medication to maintain their response to acid suppressive therapy.

The management of patients with suspected laryngeal manifestations of GERD continues to be controversial. [8] Issues are whether laryngopharyngeal reflux is a real disease, whether laryngeal physical exam in patients with symptoms of GERD is useful as a marker for response to treatment, how to differentiate and treat patients with chronic laryngitis with and without reflux symptoms, and the benefits of PPIs in patients with different symptoms. Continued acid suppression is unlikely to provide dramatic symptom improvement for patients whose conditions are completely unresponsive after 1-2 months of treatment with twice-daily PPI. Vaezi et al state "Any suggestions that reflux still may be playing a role in patients refractory to therapy, especially if suggested by nonspecific laryngeal findings, is a less than optimal use of resources and should be discouraged." [8]

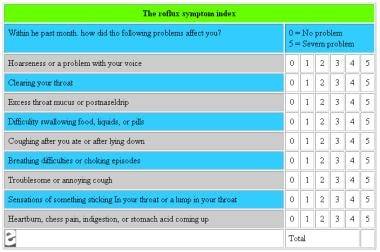

The image below is a scoring system for presence and degree of symptoms.

Pathophysiology

Major factors that have led clinicians to associate chronic supraesophageal disorders with reflux of gastric acid include the frequent lack of an etiology for some chronic laryngeal symptoms and findings, the recurrent or persistent nature of these disorders, and the benefit of empiric antireflux treatment as reported by multiple observational studies. However, the cause-effect relationship has been difficult to establish for several reasons, including the following:

-

GERD is a prevalent disorder, but only a small proportion of these patients have supraesophageal problems.

-

Although a significant subset of these patients may have abnormal esophageal acid exposure, in most patients, esophageal symptoms or esophagitis is absent.

-

Ascertaining whether supraesophageal disorders result from neurally mediated cough and chronic throat clearing or from direct injury from mucosal contact with substances in the refluxate has been difficult. However, most believe that the mucosa of the pharyngolarynx is not designed to handle the direct injury of acid or pepsin found in the refluxate.

-

Response to agents that inhibit gastric acid secretion has not been as clear as response for esophageal signs and symptoms of reflux disease.

Unfortunately, a direct relationship between refluxed gastric acid and most of these suspected supraesophageal complications have been difficult to conclusively establish to date. This dilemma is further complicated by the fact that patients with suspected pharyngeal and laryngeal complications of reflux disease frequently lack the characteristic features of GERD, including its symptom of heartburn, and some patients may have suspected reflux-induced supraesophageal and esophageal peptic injuries, which are independent of each other.

Two hypotheses exist about how gastric acid precipitates extraesophageal pathologic response. The first purports direct acid-pepsin injury to the larynx and surrounding tissues. The second hypothesis suggests that acid in the distal esophagus stimulates vagal-mediated reflexes that result in bronchoconstriction and chronic throat clearing and coughing, eventually leading to mucosal lesions. These 2 mechanisms may act in combination to produce the pathologic changes seen in laryngopharyngeal reflux (LPR). [9]

The following 4 physiological barriers protect the upper aerodigestive tract from reflux injury:

-

The lower esophageal sphincter

-

Esophageal motor function with acid clearance

-

Esophageal mucosal tissue resistance

-

The upper esophageal sphincter

The delicate ciliated epithelium of the respiratory tract is sensitive to damage when these mechanisms fail. Dysfunction in the cilia leads to mucus stasis. The accumulation of mucus produces sensations that provoke chronic throat clearing. Direct irritation of the upper airway by gastric refluxate can cause laryngospasm, producing symptoms of chronic coughing and choking.

The combination of direct injury by refluxate and symptoms such as chronic laryngospasm and throat clearing can lead to vocal cord edema, contact ulcers, and granulomas that cause other LPR-associated symptoms such as hoarseness, globus pharyngeus, and sore throat.

Evidence suggests that in both healthy and patient populations the refluxed gastric acid may come into contact with structures as high as the pharynx. Furthermore, several signs of laryngeal irritation, which are generally considered to be signs of laryngopharyngeal reflux (LPR), were found to be present in a high percentage of asymptomatic individuals on laryngoscopic examination. [4]

These findings suggest the existence of interindividual variability in terms of mucosal resistance to acid exposure, both in the esophagus and pharyngolarynx. Currently, the understanding of the pharyngolaryngeal defense mechanisms against refluxed acid is limited, and the natural history of the disease is unknown. This problem is further magnified by the fact that pharyngolaryngeal lesions may have multiple etiologies with similar appearance and presentation.

More recent investigation into defense mechanisms against refluxed acid in the larynx and surrounding tissues suggests a possible mechanism of increased susceptibility in some patient populations. Defense mechanisms in the epithelium of the esophagus and larynx are known to differ. Active bicarbonate production is pumped into the extracellular space in the esophagus but not into the larynx. Recent investigations suggest that laryngeal tissues are protected from reflux damage by a carbonic anhydrase in the mucosa of the posterior larynx. The carbonic anhydrase enzyme catalyzes hydration of carbon dioxide to produce bicarbonate, which neutralizes the acid in refluxate. Carbonic anhydrase isoenzyme III, expressed at high levels in normal laryngeal epithelium, was shown to be absent in 64% of biopsy specimens from laryngeal tissues of laryngopharyngeal reflux (LPR) patients. [10]

A study by Eckley et al indicated that persons with reflex laryngitis have lower concentrations of salivary epidermal growth factor (EGF) than do healthy controls, even after treatment, suggesting a lack of protective mechanisms in these individuals against GERD. [11]

Despite the common understating that reflux of acid causes respiratory symptoms, a recent prospective study from Sweden found that a 10-year follow-up of individuals with esophageal and pharyngeal acid exposure did not correlate with increase risk of airway symptoms or laryngeal abnormalities. [12]

Epidemiology

Frequency

United States

GERD is one of the most common disorders; US population surveys, for example, suggest that as many as 50% of adults (or 60 million people) have symptoms of heartburn at least once a month. More than one quarter of adult Americans use antacids 3 or more times per month. Although nearly half of the US population experiences occasional heartburn, only 4-7% report daily symptoms. This group of patients most likely represents those with significant esophageal complications of reflux disease.

The true incidence of GERD might be underestimated because of the relatively low proportion of individuals who seek medical attention for reflux symptoms. One report found that only 5% of patients with symptoms of heartburn and regurgitation had visited a physician because of this problem within the preceding year. An estimated 4-10% of chronic nonspecific laryngeal disorders in otolaryngology clinics are associated with reflux disease.

A retrospective review showed a significant increase in US ambulatory care visits for GERD, from a rate of 1.7 per 100 to 4.7 per 100 over 12 years. Otolaryngologists appeared to have an increasingly prominent role in management of this disease. [13]

International

In a Brazilian study of children and adults with dysphonia, Martins et al found that among 1305 adults aged 19-60 years, reflux laryngitis was the second most prominent cause of the problem (164 patients, 12.6%), behind functional dysphonia (268 patients, 20.5%). [14]

Mortality/Morbidity

Symptoms of laryngopharyngeal reflux are more prevalent in patients with esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC) than typical GERD symptoms and may represent the only sign of disease. Chronic cough is an independent risk factor associated with the presence of EAC. [6] Therefore, laryngopharyngeal reflux (LPR) symptoms should be assessed in the screening for esophageal cancers and Barrett esophagus. Laryngopharyngeal reflux (LPR) may be a significant risk factor for the development of EAC.

Chronic laryngopharyngeal reflux (LPR) is a risk factor for symptomatic subglottic stenosis, laryngeal malacia, laryngeal stenosis, and laryngeal carcinoma.

A study by Kang et al indicated that an association exists between laryngopharyngeal reflux (LPR) and insomnia, finding that 46.3% of the report’s patients with LPR had insomnia, compared with 29.5% of healthy controls. Moreover, the severity of the insomnia tended to be greater in persons with more severe LPR-related symptoms. [15]

Race

No particular racial predilection reported.

Sex

A slightly higher prevalence in males than females may exist (55% vs 45%).

Age

The percentage of patients with GERD who are older than 44 years appears to be slowly growing.

-

The RSI documents the presence and degree of nine laryngopharyngeal reflux (LPR) symptoms both before and after treatment; maximum score: 45.

-

The reflux finding score (RFS) documents the presence and degree of eight laryngopharyngeal reflux (LPR) findings during fiberoptic laryngoscopy; maximum score: 26.