Practice Essentials

Glottic stenosis is narrowing of the larynx at the level of the glottis (ie, vocal cords). It is caused by webbing, fibrosis, or scarring and most often involves the posterior glottis. The most common cause of stenosis is prolonged endotracheal intubation. In patients who are intubated for more than 10 days, the risk of developing posterior glottic stenosis is as high as 15%. Inflammation, infection, trauma, and congenital and iatrogenic causes also contribute to glottic stenosis. In all cases, the preoperative evaluation must include direct laryngoscopy as well as microlaryngoscopy with an assessment of vocal cord mobility. Treatment is based on the etiology of the stenosis and the thickness of the stenotic segment. Various medical and surgical methods are discussed according to the type of stenosis. [1, 2]

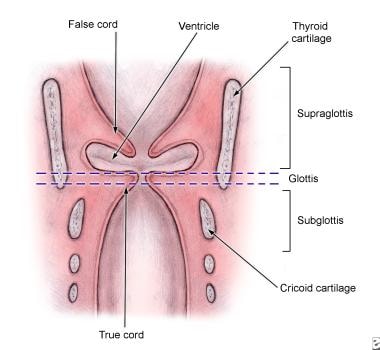

Anatomic regions of the larynx are shown in the image below.

Signs and symptoms

Congenital glottic stenosis in the form of laryngeal webs typically manifests with symptoms of airway distress or obstruction, a weak or husky cry, and, occasionally, aphonia.

In general, a patient with posterior glottic scarring tends to present with dyspnea, while a patient with anterior glottic scarring presents with dysphonia.

Acquired anterior glottic webs may produce symptoms that range from hoarseness to respiratory distress. Posterior glottic stenosis can manifest as airway stenosis and may mimic bilateral vocal cord paralysis. [3]

Workup

Few diagnostic laboratory findings are associated with glottic stenosis, although performing a serologic workup is necessary if a granulomatous disease (eg, sarcoidosis, tuberculosis, syphilis, Wegener granulomatosis) or a systemic disease (eg, rheumatoid arthritis, amyloidosis) is suspected as the cause.

A computed tomography (CT) scan allows for evaluation of the length and thickness of the glottic stenotic segment in subglottic stenosis. A CT scan also allows for evaluation of the laryngeal framework in order to determine the presence of a fracture or other significant injury. Spiral CT scanning with 3-dimensional reconstruction is advisable for better surgical planning and outcome. [4]

Electromyography (EMG) can help to differentiate posterior glottic stenosis from bilateral vocal cord paralysis. It may also be used to evaluate the function of the intrinsic muscles of the larynx.

Under anesthesia, direct laryngoscopy and bronchoscopy in the operating room allow for careful evaluation of the laryngeal and distal airways and provide a means of assessing the cricoarytenoid joints.

Management

Treatment consists of medical therapy, intralesional injections, endolaryngeal procedures, and open surgical procedures. The treatment depends on the thickness of the glottic web. Thin anterior commissure webs can be successfully excised with a carbon dioxide laser or microdebrider followed by endoscopic keel placement, while thicker webs require laryngofissure, lysis of the web, and placement of a silicone or silastic keel.

When stenosis is due to an infection or inflammatory disorder, appropriate treatment in the form of antibiotics, corticosteroids, or both is important.

Surgery

Open surgical techniques involve an anterior laryngofissure or thyrotomy with grafting or placement of keels or stents.

In congenital glottic stenosis, the thickness of the webs determines the treatment modality. Thin webs that transilluminate respond well to endoscopic lysis (either sharply with microscissors or with a carbon dioxide laser or a microdebrider) or serial dilations. Thicker webs, in approximately 40% of patients, require tracheotomy with a subsequent open laryngeal repair.

Overall, the trend in glottic stenosis management is toward shorter stenting periods and less invasive techniques (eg, endoscopy, use of carbon dioxide laser, or a smaller laryngofissure).

History of the Procedure

Congenital subglottic stenosis was first described by Rossi in 1826. Mackenzie in 1862 described laryngeal stenosis that results from inflammatory conditions, especially syphilis, which was predominant then. [5] In the late 19th century, Von Schroetter performed laryngeal dilatation with rigid vulcanite tubes and used pewter plugs for stents. [6]

In 1924, Haslinger described an endoscopic technique for web excision with placement of a silver plate keel. [7] In 1935, Iglauer described the use of a spring ring from a watch chain as a keel after glottic stenosis excision. [8] In 1950, McNaught used a tantalum keel postglottic stenosis excision. [9]

In 1979 and 1980, Dedo and Lichtenberger, respectively, modified this technique for clinical use. [10, 11] In 1980, Lichtenberger introduced a technique for the treatment of anterior commissure webs. This technique involved endoscopically suturing a keel in place from inside the airway out to the neck. In 1994, Lichtenberger reported on a series of 13 patients who were treated for anterior commissure webs with a keel-fixing technique that involved the use of a specialized endo-extralaryngeal needle carrier. [11]

In 1968, Dedo and Sooy described an aryepiglottic fold mucosal flap. In 1984, they detailed the endoscopic use of the laser for mild posterior commissure stenosis and described the creation of a trapdoor flap. [10] In 1973, Montgomery recommended a superiorly based advancement mucosal flap from the interarytenoid area. [12] Multiple variations of the laryngofissure approach have been developed.

In 1993, Zalzal described an anterior laryngofissure technique with posterior cricoidotomy and cartilage grafting. [13] In 1995, Biavati et al successfully used, in 5 children, a single-stage procedure for the repair of congenital laryngeal webs that were associated with subglottic stenosis. [14] Recent work has centered around endoscopic techniques for repair, use of a carbon dioxide laser or microdebrider for excision of webs, topical application of mitomycin-C, and, lately, chitosan for prevention of restenosis.

Problem

Glottic stenosis may accompany subglottic stenosis or may be diagnosed as a separate entity. Glottic stenosis may be a congenital or an acquired condition, represented as anterior or posterior webs, interarytenoid adhesions with or without impaired vocal cord mobility, or complete fusion of the true vocal folds (rare).

Epidemiology

Frequency

Acquired posterior glottic stenosis is the most common form of glottic stenosis and typically results from trauma due to endotracheal intubation. The risk of developing posterior glottic stenosis is reported to be as high as 15% in patients who are intubated for more than 10 days. Factors that contribute to increased risk of stenosis related to intubation include traumatic intubation, prolonged duration of intubation, multiple extubations and reintubations, an oversized endotracheal tube used for intubation, motion of the patient or the endotracheal tube, gastroesophageal reflux, and local infection.

Congenital glottic stenosis is a rare disorder and may exist as a thin membranous stenosis, a thick anterior or posterior web, or as a complete fusion of the vocal cords. Congenital laryngeal webs are rare; the largest study identified 51 children over a 32-year period. In 2009, Cheng et al reported on 4 children with Shprintzen syndrome who had severe congenital anterior glottic web. [15] Crowe et al have reported on a rare case of glottic stenosis in an infant with Fraser syndrome. [16]

Etiology

Congenital glottic webs result from failure of the larynx to completely recanalize during gestation. Different degrees of failure of this separation can result in webs or, rarely, in complete atresia at the glottic level. Laryngeal webs account for approximately 5% of congenital laryngeal anomalies, and 75% of the webs occur at the glottic level.

Acquired glottic stenosis is most commonly due to trauma secondary to endotracheal intubation. Other causes include caustic ingestion, infections (eg, croup, syphilis, fungus, diphtheria), foreign bodies, irradiation, or external trauma. A study by Howard et al provides photodocumentation of the progression of intubation-related mucosal injury to granulation tissue and the subsequent development of posterior glottic stenosis; the investigators stress the importance of serial examination of patients who develop persistent voice change following intubation. [17]

Iatrogenic causes of acquired glottic stenosis include traumatic endoscopic manipulation, aggressive endolaryngeal laser surgery, and vocal cord stripping procedures.

Granulomatous diseases such as tuberculosis, sarcoidosis, rhinoscleroma, or Wegener granulomatosis may also cause laryngeal glottic stenosis. Tuberculosis commonly involves the interarytenoid space and the posterior vocal cords. Sarcoid usually involves the supraglottis, while Wegener, rhinoscleroma, and histoplasmosis primarily involve the subglottis. Long-term nasogastric intubation may contribute to mucosal erosion and ulceration in the postcricoid region, which progresses to posterior stenosis.

A study by Hillel et al reported that in intubated patients, risk factors for posterior glottic stenosis include ischemia, diabetes mellitus, length of intubation time, and large endotracheal tube size. [18]

Prevention

Prevention of glottic stenosis consists of performing atraumatic intubation with the smallest endotracheal tube acceptable, limiting total time of intubation, reducing motion of the tube while patient is intubated and treating gastric reflux. Prevention also involves the avoidance of inappropriate dissection or overzealous use of the laser in endolaryngeal surgery.

Pathophysiology

Acquired posterior glottic stenosis typically begins as ulceration of the mucosa due to pressure from an endotracheal tube. Secondary infection, perichondritis, chondritis, and formation of granulation tissue occur next, which leads to scar formation and possible arytenoid fixation. However, most posterior glottic injuries heal after extubation with re-epithelialization, leaving no scars.

Presentation

Congenital glottic stenosis in the form of laryngeal webs typically manifests with symptoms of airway distress or obstruction, a weak or husky cry, and, occasionally, aphonia. Patients may present with these lesions shortly after birth and may require emergent intubation or tracheotomy if the stenosis is severe.

Seventy-five percent of congenital webs are located (usually anteriorly) at the glottic level, with the remainder located in supraglottic and subglottic areas. Occasional extension to the glottic level may occur.

In general, a patient with posterior glottic scarring tends to present with dyspnea, while a patient with anterior glottic scarring presents with dysphonia. Acquired anterior glottic webs may produce symptoms that range from hoarseness to respiratory distress. Posterior glottic stenosis can manifest as airway stenosis and may mimic bilateral vocal cord paralysis. [3] Acquired posterior glottic stenosis is usually associated with tracheotomy dependence or difficulty performing extubation, along with a history of airway difficulty that requires intubation.

Indications

See Surgical therapy.

Relevant Anatomy

Embryology

The larynx develops in early intrauterine life from the cranial end of the laryngotracheal tube and surrounding mesenchyme of the fourth and sixth branchial arches. A rapid proliferation of the laryngeal epithelium causes temporary occlusion of the laryngeal lumen. Thus, the vocal cords adhere to each other during the seventh week of gestation. Over a period of 2 weeks, this epithelial fusion deteriorates and leaves an opening between the cords. Different degrees of failure of separation can result in glottic webs or, rarely, complete atresia at the level of the glottis.

Anatomy

The larynx is divided into 3 distinct anatomical regions as seen in the image below: the supraglottis, the glottis, and the subglottis. The glottic segment of the larynx is composed of the true vocal cords, the anterior and posterior commissures, and the vocal processes of the arytenoid cartilages. The superior border of the glottis is the ventricle, which separates the glottis from the supraglottic region. The inferior border is located at the inferior limit of the true vocal cord. The glottis is approximately 5 mm at the midportion of the true vocal cord, its longest point, and tapers to 2-3 mm at the anterior commissure.

See the image below.

The posterior commissure is a strip of mucosa that measures approximately 5 mm in height. This strip extends across the interarytenoid space from one vocal process to the other. The posterior glottis consists of the posterior third of the vocal cords, the posterior commissure with the interarytenoid muscle, the cricoid lamina, the cricoarytenoid joints, the arytenoids, and the overlying mucosa. The anterior glottis is lined with squamous epithelium, while the posterior glottis shares respiratory epithelium with the subglottis.

Contraindications

In general, patients who require peak airway pressures above 35 mm Hg are poor surgical candidates. When reconstruction is necessary, surgery may be delayed if the patient's medical condition precludes prolonged anesthesia for any reason. Similarly, reconstruction in infants and children with a history of bronchopulmonary dysplasia may also be deferred until they experience a period without hospitalization for severe respiratory illness.

Guidelines for laryngotracheal reconstruction that are important to consider prior to repair include weight of at least 10 kg, no need for ventilatory support, and control of gastroesophageal reflux or asthma.

-

Anatomical regions of the larynx.