Practice Essentials

Bilateral vocal fold (vocal cord) immobility (BVFI) is a broad term that refers to all forms of reduced or absent movement of the vocal folds.

Bilateral vocal fold (cord) paralysis (BVFP) refers to the neurologic causes of bilateral vocal fold immobility (BVFI) and specifically refers to the reduced or absent function of the vagus nerve or its distal branch, the recurrent laryngeal nerve (RLN). [1]

Vocal fold immobility may also result from mechanical derangement of the laryngeal structures, such as the cricoarytenoid (CA) joint. This is often termed posterior glottic stenosis (PGS).

Although sometimes difficult to determine, it is important to distinguish which process is present, as evaluation and management differ between the two processes.

Obtention of a thorough history and use of fiberoptic laryngoscopy are the mainstays of clinical assessment.

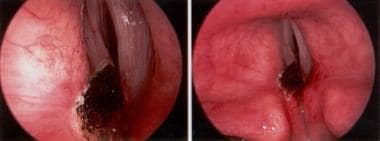

Direct laryngoscopic view of the larynx in a patient who with bilateral vocal fold immobility (BVFI) is shown. Palpation of the arytenoids revealed cricoarytenoid (CA) joint ankylosis. Close inspection of the interarytenoid space demonstrated interarytenoid scar. This condition is posterior glottic stenosis (PGS).

Direct laryngoscopic view of the larynx in a patient who with bilateral vocal fold immobility (BVFI) is shown. Palpation of the arytenoids revealed cricoarytenoid (CA) joint ankylosis. Close inspection of the interarytenoid space demonstrated interarytenoid scar. This condition is posterior glottic stenosis (PGS).

Although a small number of conditions account for most cases of vocal cord immobility, this article presents a comprehensive differential diagnosis, followed by the clinical presentations, diagnostic workup, and treatment options. The goal of the article is to provide the clinician with a basic understanding of the rare entity of bilateral vocal fold immobility (BVFI). [2]

Signs and symptoms of bilateral vocal fold immobility

The physical examination can reveal the following:

-

The voice can be breathy or normal

-

Airway findings can range from biphasic stridor to normal

-

Unless patients describe gross aspiration with swallowing, their swallowing function can be challenged by having them sip a small amount of water

Workup in bilateral vocal fold immobility

History is essential, as this will reveal any recent surgical procedures that may have resulted in injury to the vagus or recurrent laryngeal nerves. It will also reveal medical or neurologic conditions predisposing the patient to vocal fold paralysis or fixation.

Fiberoptic laryngoscopy is the mainstay of clinical assessment. Direct laryngoscopy under anesthesia allows examination of the posterior glottis and palpation of the arytenoid cartilages. This exam is sometimes an essential step in clarifying the nature of vocal fold immobility.

Computed tomography (CT) scanning along the entire length of the vagus nerve from the skull base to the superior mediastinum may be necessary when no cause of bilateral vocal fold (cord) immobility (BVFI) is initially identified. This test will also assess the structure of the larynx and help to determine if intralaryngeal pathology is present.

Features of patient history and clinical findings may suggest that the following studies be performed:

-

Serum K + level

-

Serum Ca + level

-

Blood glucose

-

Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)

-

Venereal disease research laboratory (VDRL) test

-

Lyme disease titer

-

Tuberculosis (TB) skin test

-

Uric acid level

-

Rheumatoid factor (RF)

-

Antinuclear antibody (ANA)

-

Sedimentation rate (ESR)

Management of bilateral vocal fold immobility

Medical management of inflammatory conditions of the cricoarytenoid (CA) joint (eg, gout, rheumatoid arthritis) and the laryngeal mucosa (eg, syphilis, tuberculosis) that result in mechanical fixation may improve the patient's airway. Corticosteroids may be effective in several conditions (eg, Wegener granulomatosis, sarcoidosis, polychondritis).

Depending on the patient's presentation, surgical procedures for bilateral vocal fold (cord) paralysis (BVFP) include the following:

-

Tracheostomy

-

Permanent procedures such as posterior vocal fold cordotomy, or partial or complete arytenoidectomy, cordopexy lateralization, and arytenoid abduction lateropexy

-

Less frequent and experimental procedures include reinnervation techniques (experimental) [3] and electrical pacing (experimental){ref3}

Surgical procedures for bilateral vocal fold (cord) immobility (BVFI) or posterior glottic stenosis (PGS) due to interarytenoid (IA) scarring, with or without cricoarytenoid (CA) ankylosis, include the following:

-

Tracheostomy

-

Permanent procedures such as cordotomy or arytenoidectomy but that also include microflap removal of the interarytenoid scar, laryngofissure with arytenoidectomy, posterior cricoidotomy with stent and/or graft placement, and endoscopic lateralization techniques; there are also innovative techniques such as placement of a self-retaining interarytenoid spring and cricoarytenoid release

History of the Procedure

The history of the procedures used to treat vocal cord immobility begins in 1855 with Garcia's work on mirror laryngoscopy. In the 1860s, Turk and Knight first described vocal cord paralysis. In 1922, Chevalier Jackson performed the first surgical procedure for bilateral vocal fold immobility (BVFP) when he endoscopically resected a vocal cord. He provided an airway at the expense of voice and airway protection. This dilemma continues to plague present surgeons. Since 1922, pioneers in laryngology have described arytenoidectomy, described vocal cord lateralization, and introduced the use of laser.

Etiology

According to Benninger's findings in a series of 117 cases, BVFI can be attributed to the following causes: surgical trauma (44%), malignancies (17%), endotracheal intubation (15%), neurologic disease (12%), and idiopathic causes (12%). [4] In adults, conditions that mimic vocal fold immobility include paradoxical vocal fold motion and functional disorder.

Therefore, in most clinical practices, BVFI results from paralysis or fixation of vocal folds from an iatrogenic cause. This is often evident when a satisfactory history is obtained. Realizing this, a focused workup and treatment plan can be undertaken in the vast majority of patients.

When the etiology or treatment plan is uncertain, a more thorough review of causes and treatment alternatives is worth considering.

Causes of bilateral vocal fold paralysis

Iatrogenic

These include the following:

-

Open cervical procedures such as bilateral thyroid or parathyroid surgery, esophageal or tracheal procedures, carotid artery endarterectomy and cervical disc procedures (particularly when surgery on the contralateral side was performed previously), and endolaryngeal surgery affecting the cricoarytenoid joint

-

Intracranial procedures, particularly when brainstem surgery is performed.

-

Endotracheal intubation resulting in trauma to the recurrent laryngeal (RL) nerves as they enter the larynx, usually from compression

-

Nasogastric tube compression of RL nerves

-

Esophageal stent compression of RL nerves

Neurologic

These include the following:

-

Arnold-Chiari malformation

-

Meningomyelocele

-

Diabetic neuropathy

-

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

-

Bulbar palsy

-

Myasthenia gravis

-

Mobius syndrome

-

Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease

-

Postpolio syndrome

-

Shy-Drager syndrome

-

Creutzfeldt-Jacob disease

-

Hydrocephalus

-

Lyme disease

-

Cerebrovascular accident

-

Parkinsonisms

-

Neoplasms or sarcoidosis involving the mediastinum, resulting in RL nerve compression

-

In children - Arnold-Chiari deformity with hydrocephalus is a recognized cause, but nonspecific central nervous system (CNS) insults such as craniotomy and hypoxia can result in BVFP

Metabolic

These include the following:

-

Hypokalemia

-

Hypocalcemia

-

Renal insufficiency with Alport syndrome [5]

Toxins

These include the following:

-

Vincristine

-

Paclitaxel

-

Organophosphates [6]

Idiopathic

In adults, this category is confounding but accounts for a relatively small number of cases

Idiopathic causes are the second most common causes of childhood bilateral vocal fold paralysis (BVFP). Some researchers postulate that the etiology in some children with bilateral vocal fold paralysis (BVFI) is an imbalance between the adductors and abductors of the larynx that results in adducted vocal folds. With time, a balance is restored and symptoms abate as children mature. Although conjectural, this explanation fits with the clinical course of most children with bilateral vocal fold paralysis (BVFI) who spontaneously improve with time. Gacek hypothesized that fewer abductor fibers exist; therefore, injury to the nerve is more likely to cause abductor dysfunction. [7]

Causes of bilateral vocal fold fixation

Vocal fold fixation or mechanical derangement of the posterior glottis may also be referred to as posterior glottic stenosis (PGS). Bogdasarian and Olson classified PGS into the following four grades [8] :

-

Grade I - Interarytenoid scarring with normal posterior commissure

-

Grade 2 - Interarytenoid and posterior commissure scarring

-

Grade 3 - Posterior commissure scarring involving one cricoarytenoid joint

-

Grade 4 - Posterior glottic scarring involving both cricoarytenoid joints

Iatrogenic

Causes include the following:

-

Prolonged intubation

-

Arytenoid dislocation with traumatic intubation

Inflammatory processes

These include the following:

-

Rheumatoid arthritis

-

Gout

-

Tietze syndrome

-

Ankylosing spondylosis

-

Reiter syndrome

-

Crohn's disease

-

Collagen vascular diseases

-

Systemic lupus erythematosus

-

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener granulomatosis)

-

Cicatricial pemphigoid

-

Gastroesophageal reflux

-

Relapsing polychondritis

Infiltrative processes

These include the following:

-

Amyloidosis

-

Sarcoidosis

Infectious processes

These include the following:

-

Tuberculosis

-

Syphilis

-

Coccidiomycosis

Malignancy

Laryngeal neoplasms that can result in bilateral vocal fold fixation include squamous cell carcinoma and occasionally chondromas, chondrosarcomas, solitary fibrous tumors, and schwannomas.

Radiation injuries

These include the following:

-

Post-irradiation fibrosis

-

Chondronecrosis

Pathophysiology

Although a comprehensive discussion of each of the causes is beyond the scope of this article, some principles should be emphasized. With the first episode of bilateral vocal fold paralysis (BVFP), patients may have dysphonia because the vocal cords are too far apart. Over time, however, the vocal cords can move to a medial position, and the patient may have a good voice and cough despite stridor and bilateral vocal fold paralysis (BVFP). As the vocal cords migrate toward the midline, the voice (and cough) improves, while the airway worsens. Clinicians should not mistake a good voice and cough as signs of a functioning larynx, especially in a patient with stridor. Aspiration and dysphagia may or may not be present in patients with vocal cord paralysis.

Presentation

History

The importance of a complete history cannot be overstated. The history should include the following:

-

Chief symptom, as related to airway, voice, or swallowing [9]

-

Onset of symptoms (acute, subacute, chronic)

-

Changes in the voice and airway over time

-

Related events such as intubation, surgery, or other medical conditions that can affect vocal cord mobility

In children, obtaining a history of birth trauma, central nervous system abnormality, intubations, or surgeries is important.

Physical examination

The physical examination should include listening to the voice and airway as the patient relays his or her history.

-

The voice can be breathy or normal.

-

Airway findings can range from biphasic stridor to normal.

-

Unless patients describe gross aspiration with swallowing, their swallowing function can be challenged by having them sip a small amount of water.

The standard head and neck examination should include careful evaluation of the larynx. Evaluate the following:

-

Mucosal color and condition

-

Stenosis or scarring of the posterior glottis

-

Mobility of the arytenoids

-

Muscle mass and tone of each vocal cord

-

Length of each vocal cord

-

Asymmetry of the vocal cords

Indications

Adults

Only the patients with severe bilateral vocal fold (cord) immobility (BVFI) require surgical intervention. Patients with medical conditions (eg, rheumatoid arthritis, Wegener granulomatosis, gout) or neurologic conditions (eg, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis [ALS], Parkinsonism, stroke) rarely require surgical intervention because treatment of the underlying condition often improves airway compromise.

For patients with bilateral vocal fold paralysis (BVFP) due to iatrogenic injury in which the RL nerve or vagus nerve is damaged (neurapraxia) but not severed, permanent surgical treatment should be postponed for at least 6 months after injury to allow spontaneous recovery. In some centers, laryngeal electromyographic (EMG) monitoring can be helpful in obtaining an index of potential recovery. Obtaining a baseline EMG 30-40 days after injury and second EMG 1 month later can help in evaluating the recovery status of the vocal cords (Munin). [10] On the basis of the surgeon's clinical judgment, tracheostomy for patients with quickly deteriorating airways should be initiated quickly.

For adult patients with bilateral vocal fold (cord) paralysis (BVFP), the literature supports use of an endoscopic approach, with either posterior cordotomy or limited arytenoidectomy as the initial procedure of choice. Suture lateralization (such as the Lichtenberger needle lateralization technique) may play an adjunctive role. All of these are static permanent procedures; therefore, they should be undertaken only after spontaneous improvement has failed to occur or if EMG findings suggest permanent injury.

For patients with bilateral vocal fold immobility (BVFI) caused by PGS, serial endoscopic approaches with scar lysis or microflap trapdoor reconstruction of the interarytenoid (IA) region can be attempted before the static procedures are used.

Airway obstruction refractory to the above measures is particularly vexing. Treatment options include laryngofissure with arytenoidectomy, IA reconstruction, posterior cricoidotomy with stent placement, posterior cricoidotomy with grafting, and lateralization procedures with endoscopic suturing techniques (eg, arytenoid abduction lateropexy). The literature is less clear concerning the indications for each of these approaches than those for other procedures.

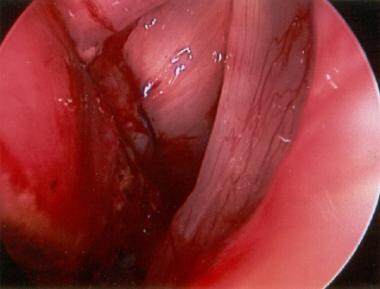

Direct laryngoscopic view of a lateralized left true vocal fold (TVF) is shown. Use of a Lichtenberger needle holder facilitates vocal fold lateralization. Posterior cordotomy or submucous resection of the vocal fold precedes suturing.

Direct laryngoscopic view of a lateralized left true vocal fold (TVF) is shown. Use of a Lichtenberger needle holder facilitates vocal fold lateralization. Posterior cordotomy or submucous resection of the vocal fold precedes suturing.

Children

Surgical intervention is indicated when respiratory effects are significant. Cordopexy or arytenoidopexy, along with partial or complete arytenoidectomy, can help solve the airway problem during the ensuing months or years as one waits for possible recovery of the contralateral cord. Children with bilateral vocal fold paralysis (BVFP) require tracheostomy only when the airway fails to improve with other measures. Findings of a literature review suggest that the airway can be managed expectantly, without a tracheostomy. Endoscopic management plays a limited role in children and is useful only for mild fixed stenosis and for revisional procedures in children who have undergone open procedures.

Relevant Anatomy

A review of vagus nerve and RLN anatomy is necessary to understand potential injuries that can cause vocal cord paralysis. The vagus nerve originates in the nucleus ambiguus of the medulla oblongata. At that point, it is composed of cells that receive neural input from the Broca area via decussating corticobulbar tracts; thus it provides input to both the right and left nuclei. Neural input from the cerebellum and extrapyramidal centers, as well as from visceral afferents, provides proprioceptive input that modulates the motor function of the vagus nerve at this site.

The motor fibers or visceral efferents that affect the larynx and pharynx occupy 2 specific sites within the nucleus ambiguus. One site becomes the superior laryngeal nerve (SLN); the other, the RLN. The vagus nerve leaves the medulla and enters the jugular foramen, along with the accessory nerve and jugular vein. Within the jugular foramen, the vagus nerve widens to form the superior ganglion, where the cell bodies of the sensory component of the nerve reside (somatic sensory). They provide sensation to the ear canal skin (Arnold nerve). As the vagus nerve exits the jugular foramen, it widens again to form the nodose ganglion, in which nerve cell bodies containing the sensory or visceral afferents from the larynx and pharynx reside.

Immediately distal to the nodose ganglion, the SLN exits the vagus nerve and courses along the carotid artery to the larynx, where it enters the larynx through the thyrohyoid membrane, dividing into internal and external branches. The internal branch provides sensory function (visceral afferent), and the external branch provides motor function to the cricothyroid muscle (visceral efferent). The vagus nerve then descends in the neck immediately lateral to the carotid artery.

The right RLN fibers exit from the vagus nerve as the nerve crosses anteriorly over the subclavian artery. The RLN loops posteriorly around the subclavian artery to enter the larynx through the Killian-Jamieson area or superior to the fibers of the cricopharyngeal muscle entering the larynx at the cricothyroid space.

The left RLN divides much further in the mediastinum, exiting the vagus nerve as it crosses anterior to the aorta and lateral to the ligamentum arteriosum (ie, remnant of the patent ductus arteriosum between the aorta and the pulmonary vein). It then extends superiorly to enter the larynx opposite the right RLN. The RLN branches into the posterior sensory branch and the motor anterior branch to the posterior cricoarytenoid (PCA), IA, lateral cricoarytenoid (LCA), and thyroarytenoid (TA) muscles. The IA muscle is the only motor branch that receives bilateral innervation, which allows some movement of both vocal folds when one RLN is nonfunctional.

-

Direct laryngoscopic view of the larynx in a patient who with bilateral vocal fold immobility (BVFI) is shown. Palpation of the arytenoids revealed cricoarytenoid (CA) joint ankylosis. Close inspection of the interarytenoid space demonstrated interarytenoid scar. This condition is posterior glottic stenosis (PGS).

-

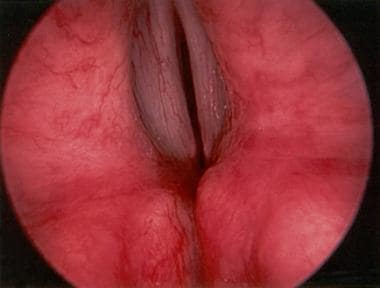

Direct laryngoscopic view of larynx after left posterior cordotomy

-

Direct laryngoscopic view of a lateralized left true vocal fold (TVF) is shown. Use of a Lichtenberger needle holder facilitates vocal fold lateralization. Posterior cordotomy or submucous resection of the vocal fold precedes suturing.