Background

Microtia repair provides many challenges to the facial plastic surgeon. [1] It requires the maintenance of the 3-dimensional details of an ear under the coverage of a 2-dimensional skin surface. In addition, an aesthetically pleasing result requires symmetric position, adequate projection, and dependable longevity. All of these factors contribute to microtia repair being one of the most demanding yet rewarding procedures to perform. The reconstructed auricle has an immeasurable positive psychological and emotional impact on the self-esteem of a young child with microtia. This article reviews the history and pertinent evaluation of microtia repair, and it includes a detailed description of the surgical techniques currently considered the criterion standard.

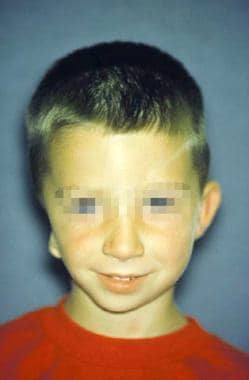

The image below depicts microtia.

History of the Procedure

Microtia repair was first reported by Sushruta in 600 BC. He noted that the surgeon should "slice off a patch of living flesh from the cheek of a person devoid of ear lobes in a manner so as to have one of its ends attached to its former seat.” [2] In 30 AD, Celsus recommended advancement flaps, and, in 1575, Pate used an ear prosthesis made of enameled metal.

Following these initial descriptions, a major progression occurred with the use of cartilage to repair the defect. In 1920, Gillies first reproduced the auricle by burying rib cartilage under the mastoid skin and then separating the ear from the underlying skin with a cervical flap. [3] Subsequently, in 1937, Gillies also attempted maternal cartilage for ear reconstruction but noted problems with resorption. [4] Tanzer reemphasized the use of autogenous cartilage in 1964. [5] He commented on the advantages of its high viability, resistance to shrinkage and softening, and lower incidence of resorption. Other authors have also supported the use of autogenous rib cartilage as the most reliable material in reconstructing microtic ears, including a description by Brent of more than 1200 cases of microtic ear reconstruction. [6]

Problem

Microtia is strictly defined as a small auricle, but an array of deformities exists, each having different implications in terms of optimum treatment and expectations. No universal classification system of microtia predominates; however, multiple authors have described systems based on the degree of deformity and specific anatomic parts. Marx described a microtia staging system that consists of the following 4 levels: [7]

-

Grade 1 microtia is characterized by an abnormal auricle with all identifiable landmarks.

-

Grade 2 microtia consists of an abnormal auricle without some identifiable landmarks.

-

Grade 3 microtia is recognized by a very small auricular tag

-

Grade 4 microtia is anotia.

Weerda describes the following 3 types of microtia: [8]

Grade I microtia is characterized by a mild deformity with a slightly dysmorphic helix and antihelix, as depicted in the 1st image below. All the major structures are present, and no additional cartilage is necessary during surgical repair. Characteristic lop ear and cup ear abnormalities are categorized into this group. Also, a Stahl ear has features of a third crus with a flattened scaphoid fossa and deficient antihelix, as depicted in the second image below.

Grade II microtic ear deformities have all major structures present to some degree, but repair requires cartilage or skin, as depicted in the image below. The external auditory meatus is present but with stenosis. Typical defects include severe cup ears, as depicted in the 1st image below.

The grade III abnormality is characterized by few, if any, landmarks. If present, the lobule is usually positioned anteriorly. Peanut and anotic ears are examples of grade III malformations, as depicted in the second image above.

The Tanzer microtia classification is based on the description and location of the defect, as follows: [5]

-

Type A microtia consists of an anotic ear.

-

Type B microtia describes a completely hypoplastic ear with or without aural atresia.

-

Type C microtia consists of hypoplasia of the middle third of the auricle.

-

Type D microtia is characterized by hypoplasia of the superior third of the auricle.

-

A prominent ear is classified as type E microtia.

Aguilar and Jahrsdoerfer simplified the classification into the following 3 categories: [9]

-

Grade I microtia is any normal ear that is reduced in size.

-

Grade II microtia is an ear with structural deficiencies.

-

Grade III microtia is characterized by the classic peanut deformity and includes the anotic ear.

Other authors have a more complex system consisting of numerous categories. For example, Fukuda systematizes ear deformities into 9 types based on the shape of the vestige. [10]

Another classification system developed by Firmin focuses on the type of incision required for placement of the cartilage framework, with deformities divided into 3 types:

-

Type 1 correlating with the incision for a lobular type deformity

-

Type 2 correlating with the incision for a large conchal remnant deformity

-

Type 3 correlating with the incision for a small conchal remnant deformity and varied atypical vestiges

Firmin’s classification has been endorsed in recent literature as a more useful system with practical implications for surgical technique. [11] An updated and more detailed version of this classification awaits publication and will take into consideration not only the type of incision, but also the type of framework required and the type of additional cartilage used for projection. [12]

Epidemiology

Frequency

The incidence of microtia is 1 per 5,000-20,000 births. The incidence of microtia is 1 per 900-1200 births in the Navajo population and 1 per 4000 births in the Japanese population.

The male-to-female ratio is 2.5:1. Microtia is typically unilateral rather than bilateral (unilateral-to-bilateral ratio of 4:1). The right ear is affected more frequently than the left ear (right-to-left ratio of 3:2). The reason for this predilection remains unclear.

Etiology

Although no specific chromosomal abnormality for microtia has been cited, a multifactorial inheritance is considered. An immediate family history is noted in approximately 5% of patients. Prenatal infections and teratogens such as isotretinoin, thalidomide, and maternal rubella have been implicated.

Presentation

Fifty percent of microtia cases are associated with congenital syndromes. Hemifacial microsomia is a spectrum of craniofacial malformations characterized by asymmetric facies with microtia, malar or mandibular hypoplasia, cleft palate, tragal skin tags, upper eyelid colobomas, and facial nerve paralysis, as depicted in the image below. Goldenhar syndrome is a nonhereditary variant of hemifacial microsomia associated with abnormal development of the first and second branchial arches. Associated findings include preauricular nodes, epibulbar dermoids, malar and mandibular hypoplasia, and vertebral, cardiac, or renal abnormalities.

Treacher Collins syndrome (ie, mandibulofacial dysostosis, Franceschetti syndrome) is an autosomal dominant inherited disease isolated to chromosome arm 5q. Typical features in addition to microtia include stenosis or atresia of the external auditory canal, middle ear abnormalities, antimongoloid slanting of the palpebral fissures, lower lid colobomas, partial or near absence of eyelashes, microstomia, hypoplastic zygoma and mandible, and a narrow or cleft palate. Oculoauricular vertebral dysplasia is characterized by microtia with cervical spine anomalies and epibulbar dermoids.

A number of associated abnormalities and syndromes may coexist with microtia and highlight the necessity for a thorough head and neck examination with attention to recognizing these features. In a review of 1200 cases of microtia, associated deformities included branchial arch deformities (36.5%), facial nerve weakness (15.2%), cleft lip and/or palate (4.3%), urogenital defects (4%), cardiovascular malformations (2.5%), and macrostomia (2.5%).

The evaluation for microtia repair begins with a head and neck examination that emphasizes facial asymmetry; retrognathia (or other airway concerns common to this group); integrity of the facial nerve; quality of non–hair-bearing skin in the vicinity of the auricle, hairline, position of the remnant auricle, and future lobule; and condition of the contralateral ear. The patient should be referred to an otologist if other middle or inner ear abnormalities exist.

A retrospective study by Billings et al indicated that in patients with unilateral microtia/aural atresia, there is an increased likelihood that the normal ear will suffer hearing loss and middle ear effusion requiring management with a tympanostomy tube. The study, which included 72 patients, all under age 3 years, found that 14 (19.4%) underwent tympanostomy tube placement, compared with a reported 6.8% of children under age 3 years in the general population. [13]

Indications

Patients who undergo microtia repair are typically in the pediatric age group, but patients may also include adults who have delayed seeking repair. The operative indication is the patient's desire to repair the congenital deformity. Although repair is elective in the sense that an absent auricle is not life threatening, the negative psychosocial impact of a facial malformation may cause irreparable damage to an individual's self-image. Completion of the surgical repair before the patient enters the first grade has concrete advantages during the adolescent years and is usually encouraged. However, surgical repair in younger children is usually limited by the size of their chest walls and donor site cartilage. The goals of repair should be clearly discussed to establish realistic expectations. Microtia repair aims to make the reconstructed ear less conspicuous, but the result is not necessarily an ear that appears normal under close scrutiny.

Children with microtia commonly have atresia of the ear canal as an associated abnormality. The atresia repair is performed after the microtia reconstruction to preserve the delicate mastoid skin essential for an optimal appearance of the ear. The auricle is subtly repositioned to align the meatus with the new external auditory canal. Some surgeons reserve the repair of atresia for bilateral cases because they consider the risk of damaging the facial nerve to outweigh the benefits of the operation. However, others feel that repair of a unilateral atresia is appropriate for select patients when it is performed by a qualified otologist. The repaired ear can dramatically improve hearing because it provides binaural functional hearing. [14]

Relevant Anatomy

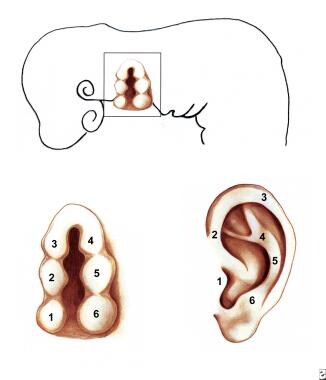

The external ear and middle ear are derived from the first and second branchial arches. By the fifth week of gestation, the external ear begins to develop as 6 small buds of mesenchyme along these arches. These hillocks, called the auricular hillocks of His, fuse during the 12th week. By the 20th week, the adult auricle is formed. Each hillock of His represents an anatomic structure of the ear, as depicted in the image below. The first 3 hillocks are formed from the first pharyngeal arch. The first hillock forms the tragus, the second hillock develops into the helical crus, and the third hillock eventually becomes the helix. The remaining 3 hillocks are formed from the second pharyngeal arch. The fourth and fifth hillocks become the antihelix, while the sixth hillock forms the antitragus.

A: Hillocks of His. B: Derivatives of the hillocks of His. The first 3 hillocks are derived from the first pharyngeal arch. The last 3 hillocks are derived from the second pharyngeal arch. The first hillock forms the tragus; the second forms the helical crus; the third forms the helix; the fourth and fifth form the antihelix; and the sixth forms the antitragus.

A: Hillocks of His. B: Derivatives of the hillocks of His. The first 3 hillocks are derived from the first pharyngeal arch. The last 3 hillocks are derived from the second pharyngeal arch. The first hillock forms the tragus; the second forms the helical crus; the third forms the helix; the fourth and fifth form the antihelix; and the sixth forms the antitragus.

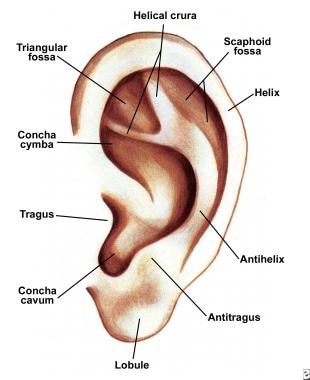

The named landmarks of the normal adult ear include the helix, antihelix, tragus, antitragus, lobule, concha cavum, concha cymba, scaphoid fossa, triangular fossa, and crura of the antihelix, as depicted in the image below. At birth, the height of the ear is 66% of adult size. The ear is approximately 85% of full size by age 6 years and 90% by age 9 years. The height of the average adult ear ranges from 5.5-6.5 cm, achieved at age 15 years in boys and age 13 years in girls. The width is approximately 55% of the height. Because the final adult size is nearly achieved by age 6 years, the contralateral normal ear serves as a reasonable template of the final auricular height. The normal protrusion from the mastoid is 1.5-2 cm or approximately 15-20°.

The primary blood supply is from the superficial temporal artery and the posterior auricular artery. Sensory innervation is provided by the greater auricular nerve (C3), lesser occipital nerve (C2, C3), auricular branch of cranial nerve (CN) X, auriculotemporal nerve (V3), and sensory twigs of CN VII and IX.

Contraindications

A contraindication for microtia repair is a patient who is too young and has inadequate chest wall development. Anxious parents often request surgical intervention at the earliest age possible, but reconstruction is usually delayed until the patient is aged 5-6 years. Moreover, the small degree of emotional maturity that occurs in the following 1-2 years often significantly affects postoperative care.

A relative contraindication relates to the expected outcomes of this challenging operation and the degree of initial auricular deformity. Because even the best repairs cannot withstand close inspection by a layperson, one should exercise caution when repairing ears that are only mildly deformed (eg, grade I microtia, grade II microtia). Smaller procedures using common otoplasty techniques with scoring and sutures are often more appropriate in such circumstances.

-

Grade I microtia.

-

Stahl ear deformity with third crus.

-

A: Grade II microtia. B: Grade III microtia.

-

Hemifacial microsomia with microtia.

-

A: Hillocks of His. B: Derivatives of the hillocks of His. The first 3 hillocks are derived from the first pharyngeal arch. The last 3 hillocks are derived from the second pharyngeal arch. The first hillock forms the tragus; the second forms the helical crus; the third forms the helix; the fourth and fifth form the antihelix; and the sixth forms the antitragus.

-

Named landmarks of the normal auricle.

-

Silastic-Dacron alloplastic implant.

-

Cartilage harvested.

-

Instruments used for carving costal cartilage.

-

Carved auricular template.

-

Microdrains in place.

-

Lobule transfer.

-

Inferiorly based lobule.

-

Lobule transferred.

-

A: Stage III, skin incision for ear elevation. B: Wedge of cartilage placed as buttress graft for projection support. C: Skin graft in position.

-

A: Stage IV, composite graft for tragal reconstruction. B: Shadow created by tragus.

-

Exposed cartilage.

-

Tissue-engineered cartilage for potential microtia repair.

-

After Stage III lateralization.

-

After atresia repair, with new ear canal.