Overview

Developmental anomalies of the nose encompass a diverse group of conditions. In this article, embryologic development of the nose and nasal cavities is discussed, as well as anomalies of the nose, including nasal dermoids, gliomas, encephaloceles, nasal clefts, proboscis lateralis, arhinia, polyrrhinia, nasopharyngeal teratoma, and epignathus. Choanal atresia is discussed in a separate chapter.

Embryology of the Nose

Development occurs through 3 distinct phases as follows: (1) the preskeletal phase, marked by development of mesenchymal swellings surrounding external nasal placodes; (2) the chondrocranial phase, which provides the nose with cartilaginous framework; and (3) the ossification phase, marked by influx of cellular elements and fusion of nasal skeletal elements. [1]

During the third week of development, ectodermal cells in the caudal portion of the developing embryo proliferate and migrate medially and caudally to form the notochordal process. Concurrently, modified ectodermal cells invaginate in the midline of the caudal primitive streak. They then migrate between ectodermal and endodermal layers. Also during the third week, the ectoderm and endoderm of the cephalic region become adherent, forming the buccopharyngeal membrane, which represents the forward boundary of the primitive foregut. At the end of the third week, a midline neural groove develops along the dorsal surface of the embryo. This groove then thickens, deepens, and forms the neural tube, the cephalic end of which becomes the primary brain vesicles.

By days 20-30, mesodermal tissue condenses on either side of the midline and becomes the paraxial mesoderm (in the cephalic region). At this point, the buccopharyngeal membrane disappears, and the primitive nasal cavity forms.

External nose

At approximately 4.5 weeks, the centrally located stomodeum appears, which forms the center of the face. The first pair of pharyngeal arches surrounds the stomodeum. The stomodeum becomes surrounded by 5 mesenchymal prominences (ie, the maxillary and mandibular swellings, as well as the frontal prominence). The nasal placode, which arises from surface ectoderm, develops on the lateral aspects of the frontal prominence.

During the fifth week of gestation, medial and lateral swellings form from the mesodermal layer and surround the nasal placode, which continues to invaginate as the olfactory pit. As the invagination continues, a tissue ridge surrounding each pit forms the nasal prominences. Prominences on the outer edge of the pits are the lateral nasal prominences; those on the inner aspect are the medial nasal prominences. The depression separating the maxillary swelling from the lateral nasal prominences is known as the nasolacrimal groove, which eventually gives rise to the nasolacrimal apparatus. The middle of the external nose develops from caudal progression of the medial nasal folds, which fuse to form the frontonasal process. Three paired centers of chondrification form the lateral nasal cartilages. Nasal septum bony formation over the cartilaginous capsule occurs during the eighth week.

Internal nose

Development requires enlargement of the nasal cavity, degeneration of existing tissues, and generation of mesenchyme-derived structures. Anterior nares form by the recession of nasal pits into the paraxial mesoderm. The primitive nasal cavity initially is a single chamber. Ectoderm of the nasal sac contacts ectoderm of the mouth roof, thereby forming the oronasal septum. Attenuation of this structure leads to creation of the oronasal membrane separating the nasal cavity from the pharynx. The oronasal membrane then undergoes degeneration, resulting in choanae formation. Subsequent development of the secondary palate and elongation of primitive nasal chambers results in final definitive nasal chambers, separated by the nasal septum.

The nasal septum begins development at week 5 and forms from the frontonasal process, which grows in an anterior-to-posterior direction, eventually joining with the tectoseptal expansion, a median ridge of mesenchyme. The septum continues growing posteriorly, ultimately uniting with palatine processes. Fusion of the frontonasal process, tectoseptal expansion, and palatine processes results in separation of the oral and nasal cavities, as well as right and left nasal chambers. The nasal septum subsequently undergoes chondrification and ossification of its various constituents.

Beginning at 6.5 weeks, lateral nasal wall development occurs. The inferior concha appears above the palatine process. As the nasal cavity heightens, ectodermal folds appear in the ethmoid region and give rise to superior, middle, and inferior concha.

Anterior to these folds appear agger nasi cells and the uncinate process, future site of the bulla ethmoidalis and hiatus semilunaris. Paranasal sinuses develop as diverticula of the lateral nasal walls, extending into maxillary, ethmoid, frontal, and sphenoid bones. Their development concludes during puberty.

Classification of nasal deformities

Losee et al (2004) developed a comprehensive classification scheme dedicated to congenital nasal anomalies. [2] This was based on a retrospective review of 261 patients with congenital nasal anomalies. Congenital nasal deformities were classified into the following 4 categories:

-

Type I - Hypoplasia and atrophy (represents paucity, atrophy, or underdevelopments of skin, subcutaneous tissue, muscle, cartilage, and/or bone)

-

Type II - Hyperplasia and duplications (represents anomalies of excess tissue, ranging from duplications of parts to complete multiples)

-

Type III - Clefts (The comprehensive and widely used Tessier classification of craniofacial clefts is applied.)

-

Type IV - Neoplasms and vascular anomalies (Both benign and malignant neoplasms are found in this category.)

Craniofacial syndromes

Nasal hypoplasia is seen with many craniofacial syndromes. Apert syndrome often manifests as bilateral narrowing of the bony nasal cavity with choanal stenosis or atresia. Fraser syndrome, a rare autosomal recessive disorder, manifests as cryptophthalmos and nasal anomalies, including a broad nose with midline groove, a depressed nasal bridge, hypoplastic nares with colobomas, choanal stenosis, and a beaklike appearance. Binder syndrome, or nasomaxillary hypoplasia, is characterized by midface retrusion, hypoplasia of the anterior nasal spine, a short columella, and an obtuse nasofrontal angle. Craniofacial microsomia and Goldenhar syndrome can both affect the nose with varying degrees of hypoplasia.

Nasal Dermoids

Etiology and embryology

Nasal dermoids are epithelial-lined cavities or sinus tracts with variable numbers of skin appendages, including hair follicles, sebaceous glands, and eccrine glands. They constitute the most common congenital nasal anomaly. Nasal dermoids may arise from clusters of epithelium trapped during ectodermal processes, or they may signify failure of ectodermal extensions into the fetal nasal septum to disappear as the septum fuses and ossifies.

The most widely accepted etiologic theory centers on the prenasal space and fonticulus, which forms between the anterior wall of the nasal skeleton and the frontal and nasal bones. Should skin remain attached to fibrous tissues of the nasal capsule in the prenasal space or the fonticulus, epidermal appendages (or other components) may be encroached upon and surrounded by the developing bones, thereby forming a tract. Dural attachments also may exist, creating a tract between the nasal skin and the dura that passes through the prenasal space (toward the foramen cecum) or fonticulus.

Clinical presentation and management

These nasal lesions account for 3.7-12% of dermoids in the head and neck and 1.1% of all body dermoids. Nasal dermoids generally occur in the midline, most commonly on the nasal dorsum, in the form of a nasal pit or nasal mass. They may manifest anywhere from the columella base to the glabella. Dermoids may be single or multiple and can manifest as a nasal mass or a fistulous tract. They often manifest with hair and sebaceous material (with or without drainage). They typically manifest within the first month of life, and 73% are diagnosed in the first year of life (see the images below).

This MRI depicts a dermoid. The dermoid is intracranial but separate from the brain. (From TL Tewfik, VM Der Kaloustian, eds. Congenital Anomalies of the Ear, Nose and Throat. New York: Oxford UP; 1997, with permission).

This MRI depicts a dermoid. The dermoid is intracranial but separate from the brain. (From TL Tewfik, VM Der Kaloustian, eds. Congenital Anomalies of the Ear, Nose and Throat. New York: Oxford UP; 1997, with permission).

Dermoids may extend intracranially and should be differentiated from encephaloceles based on their lack of transillumination and inability to enlarge with crying. Diagnose with computed tomography (CT) scan or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

A retrospective study by Herrington et al indicated that in pediatric patients with congenital nasal dermoids, preoperative examination with thin-section, high-resolution MRI with contrast offers an excellent means of assessing for intracranial extension, thereby improving the likelihood of complete lesion removal. The investigators also stated that complementary details on bone anatomy of the frontonasal area can be effectively derived using thin-section, high-resolution CT scanning. [3]

A study by Amin et al of pediatric frontonasal dermoids reported that CT scanning and MRI are comparably effective in predicting dermoid intracranial extension. According to the investigators, in terms of predicting such extensions, CT scanning and MRI have a sensitivity of 87.5% and 60.0%, respectively, and a specificity of 97.4% and 97.8%, respectively. [4]

Biopsy of dermoids is contraindicated. If infection ensues, it usually is limited to the sinus tract or cyst. Orbital/periorbital cellulitis, osteomyelitis, meningitis, or brain abscess may occur, however.

Several radiologic findings may be noted (eg, fusiform swelling within the nasal septum, widening of the nasal vault, bifid septum, glabellar destruction, bony proliferation above cyst level, large ethmoidal cystic spaces). Enlargement of the foramen cecum with crista galli involvement or deformity may allude to intracranial extension. CT scan reveals the bony defect, and MRI differentiates the dermoid element from brain tissue. Treatment involves complete cyst and sinus tract excision. [5] If an intracranial cyst exists, a combined craniofacial approach with neurosurgical consultation is required. Recurrence is attributed to incomplete excision.

A study by Kalmar et al, using the American College of Surgeons’ National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP) database, found uniformly low complication rates of 1.2% for nasal dermoid cyst excisions, whether patients underwent simple excision or more complex, transcranial excision in which the dermoid was dissected from the dura mater. This was the case even though the latter required longer operative time and more often involved inpatient care. Postoperative morbidity in excisions was driven primarily by infectious complications, the prevalence of which was 0.3%. [6]

A unique and unusual extension of the dermoid tract into the frontal sinus has been reported. It required an osteoplastic flap to access the frontal sinus floor, combined with a local midline nasal incision at the sinus tract origin.

Based on a study of 103 children with nasal dermoids, Hartley et al proposed that these lesions be classified as follows: superficial, intraosseous, intracranial extradural, and intracranial intradural. [7]

Gliomas

Etiology and embryogenesis

Gliomas are unencapsulated collections of glial cells situated outside the CNS. Possible theories of development include the following: (1) sequestration of glial tissue of the olfactory bulb entrapped during cribriform plate fusion; (2) ectopic neural tissue cells; (3) pinched encephalocele; and (4) inappropriate closure of the anterior neuropore (fonticulus frontalis), with failure of mesoderm to enter the region, resulting in inadequate bone formation.

Clinical presentation and management

Gliomas usually present in childhood as intranasal (30%), extranasal (60%), or combined masses (10%). Unlike dermoids, they do not necessarily occur in midline or attach to sinuses or skin. Gliomas form a noncompressible mass that does not increase in size on Valsalva testing and does not transilluminate. Extranasal gliomas are usually located at glabella level, but they may present laterally. [8, 9]

Intranasal gliomas are associated most often with middle turbinate or higher structures and may mimic nasal polyps. Combined intra/extranasal gliomas have a typical dumbbell shape with a connecting band. Fifteen percent of gliomas connect with the dura, either through the foramen cecum or through the fonticulus. Patients may present with unilateral nasal obstruction, unilateral nasal mass, epistaxis, or cerebrospinal rhinorrhea. Dystopia canthorum or hypertelorism is more common with extracranial lesions. Simultaneous bilateral digital compression on the internal jugular veins does not lead to distention of the mass (Furstenberg sign). Diagnosis is assisted with CT scan, which shows the bony defect, and with MR imaging, which highlights the soft tissue components. Avoid biopsy. Management consists of surgical excision of the mass.

Extranasal gliomas can be approached through standard surgical excisions. Intranasal masses that do not extend intracranially may be approached through lateral rhinotomy. Gliomas that extend intracranially require neurosurgical intervention. Avoid recurrences by removal of all gliomatous tissue.

Encephaloceles

Etiology and embryogenesis

Encephaloceles signify the herniation of neural tissue through defects in the skull. They may contain meninges (meningocele) or brain matter and meninges (encephalomeningocele), or they may communicate with a ventricle (encephalomeningocystocele). Encephaloceles have an etiology similar to that of gliomas. No familial pattern has been demonstrated with these lesions. Association with other diseases (eg, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, frontonasal dysplasia), however, may suggest a genetic component.

Clinical presentation and management

Twenty percent of all encephaloceles occur in the cranium. Of those, 15% are nasal. Nasal encephaloceles can be divided into 2 types: sincipital (60%) and basal (40%).

Further, the sincipital form is divided into subtypes as follows: (1) the nasofrontal (40%), which exits the cranium between the nasal and frontal bones; (2) the nasoethmoidal (40%), which exits between the nasal bones and nasal cartilages; and (3) the nasoorbital (20%), which exits through a defect in the maxilla frontal process. Sincipital encephaloceles typically present as soft compressible masses over the glabella.

The basal form is divided into subtypes as follows: (1) the transethmoidal, which exits through the cribriform plate into the superior meatus, extending medial to the middle turbinate; (2) the sphenoethmoidal, which exits through the cribriform plate, between the posterior ethmoid cells and sphenoid, to present in the nasopharynx; (3) the sphenoorbital, which enters the orbit via the superior orbital fissure and may produce exophthalmos; and (4) the transsphenoidal, which herniates in the nasopharynx via defects posterior to the cribriform plate. Basal encephaloceles may remain hidden (clinically) for years.

Both sincipital and basal forms expand with the Valsalva maneuver, have a positive Furstenberg sign, and transilluminate, thereby distinguishing them from gliomas. Patients may have a history of rhinorrhea or recurrent meningitis and may have a broad nose or hypertelorism (dystopia canthorum). Broekman et al (2008) described a case of intranasal encephalocele associated with Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome (BWS). [10] This rare congenital syndrome is characterized by gigantism, macroglossia, exophthalmos, postpartum hypoglycemia, and multiple midline defects such as omphalocele. Nasal masses in these patients should be carefully differentiated, as complications might be severe.

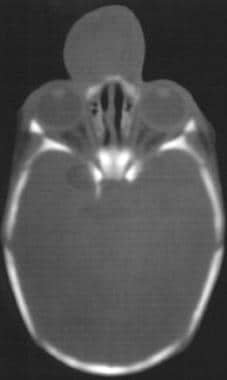

Both CT scan and MRI are useful in diagnosis, the former for degree of bony defect and the latter for degree of soft-tissue herniation (see the image below).

Biopsy is strongly contraindicated due to risk of infection and meningitis. Treatment involves surgical excision with repair of the bony defect. Often a craniotomy is necessary to approach the encephalocele.

A case study by Tan et al described the successful excision of the nasal portion of a transsphenoidal encephalocele using a combined endoscopic transnasal/transoral approach performed, with the aid of neuronavigation, on a male infant aged 48 days. [11]

Nasal Clefts

Failure of frontal processes to develop appropriately or to merge with other facial processes results in various malformations.

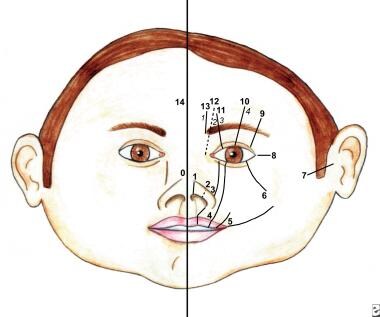

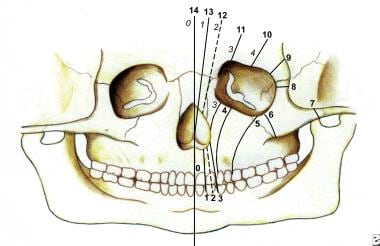

Numerous facial cleft classification systems exist. They include DeMyer, Sedano, and Tessier classifications (see the images below).

Nasal clefting may take the form of medial or lateral clefts. A rare entity, it often is associated with other congenital anomalies, or it constitutes manifestation of a syndrome, such as frontonasal dysplasia or Goldenhar-Gorlin syndrome, among others.

Nasal clefts can vary from simple groove to complete separation of either side of the nose (median cleft), or they can present as a large furrow involving the medial canthus and ipsilateral alum (lateral cleft; see the image below). Depending on the defect’s severity, reconstruction may be warranted.

Chapchay et al described nasal cleft repair surgery utilizing rearrangement of tissue existing near the cleft, with a laterally based rotational alar flap, medially based triangular flap, and nasal wall advancement flap employed. The authors reported no postoperative complications in the five study patients, each with isolated cleft, with aesthetic results considered excellent in all cases. [12]

Proboscis Lateralis and Supernumerary Nostrils

Etiology and embryogenesis

Proboscis lateralis (also known as congenital tubular nose) is an extremely rare anomaly in which the external nose fails to develop on one side and is replaced by a tubular structure emanating from the medial canthus. The condition is caused by the developmental failure or absence of medial and lateral nasal processes, resulting in fusion of the maxillary process with the contralateral nasal process.

Supernumerary, or accessory, nostrils are a very rare type of congenital nasal anomaly. They can be associated with such malformations as facial clefts and can be unilateral (most cases) or bilateral. The accessory nostril may communicate with the ipsilateral nasal cavity.

Clinical presentation and management

Proboscis lateralis is characterized by the absence of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses on one side. The nasolacrimal duct ends blindly. Proboscis lateralis may be associated with other congenital anomalies, particularly those of the CNS. Surgical treatment involves rerouting of the nasolacrimal duct and excision of the tubular deformity. Reconstruction may be a staged procedure, commencing during adolescence. Surgery for supernumerary or accessory nostrils is recommended with an early excision of the fistulous or blind tract or with a fistulo-rhinostomy, when the proximal portion is not accessible with a local skin flap to cover the defect.

Hassani et al described a 3-month-old infant with left-sided proboscis and left

lower eyelid coloboma. The proboscis was treated with local flaps at the age 3 months, and the coloboma was managed at age 10 months. [13]

Arhinia, Polyrrhinia, Nasopharyngeal Teratoma, and Epignathus

Arhinia

Arhinia is the congenital absence of the external nose, nasal cavities, and olfactory apparatus.

Etiology and embryogenesis

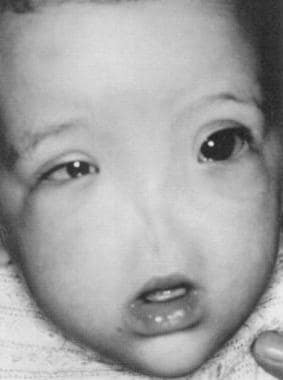

This extremely rare entity is often associated with anomalies of the ocular and central nervous systems. It has been associated with inversion and trisomy of chromosome 9 (see the image below). [14]

The photograph shows an infant with arhinia. (From Navarro-Vila et al, J Craniomaxillofac Surg 19:56, 1991, with permission).

The photograph shows an infant with arhinia. (From Navarro-Vila et al, J Craniomaxillofac Surg 19:56, 1991, with permission).

Clinical presentation and management

Arhinia constitutes a rare congenital malformation of the midface, with fewer than 25 cases previously reported. Phenotypic expression ranges from hyporhinia, manifested by the lack of external nasal structures, to total arhinia, characterized by a failure of formation of the external nose, nasal airways, olfactory bulbs, and olfactory nerve. Arhinia is clearly evident at birth, with only a depression located between the eyes (at the normal position of the external nose). Since neonates are obligate nasal breathers, respiratory distress is usually noted, but not always. The maxilla is underdeveloped, and a high arched palate is common. In 2009, Thornburg et al studied prenatal diagnosis of total arhinia. Obstetric ultrasound revealed flattened midface without a distinguished nose and a prominent upper lip. [15]

Surgical repair is staged, beginning at an approximate age of 5 years. Final revision surgery is performed near puberty. The operation creates new nasal cavities and an external nose (by use of local flaps and autologous cartilage grafts or prosthetic devices). Vertical distraction osteogenesis represents a modality for elongation of the midface. Midfacial distraction generates essential bone and soft tissues, which both improve facial aesthetic proportionality and facilitate superior reconstructive efforts.

Two Chinese siblings with a combination of nasal bone absence and brachydactyly and no other abnormalities were described by Guo et al. This combination of features has not been described previously and may represent a new familial syndrome. However, molecular genetics screening did not reveal any specific pathogenic variants. [16]

Polyrrhinia

Two completely formed noses characterize this extremely rare anomaly. Duplication of media nasal processes during embryogenesis is believed to cause polyrrhinia. Management consists of excision of the medial halves of each nose.

Nasopharyngeal Teratoma and Epignathus

Teratomas are very rare lesions that contain tissues originating from the 3 embryological germ layers. Occasionally, teratomas display differentiation into organ systems (eg, limbs). Such a teratoma is known as an epignathus.

Etiology and embryogenesis

Theories abound to explain teratoma occurrence. Some of the more accepted theories follow: (1) Teratomas arise from pathogenic development of germ cells (possibly explaining ovarian or testicular occurrence but not head and neck); (2) totipotent cells may escape embryological organization and later form teratomas; and (3) teratoma is a different embryo growing inside the body of its twin (conjoined twin theory).

Clinical presentation and management

The newborn usually presents with severe acute respiratory distress requiring endotracheal intubation or tracheotomy (see the images below). In smaller lesions, feeding difficulties may be the only presenting symptom. Investigations must rule out intracranial extension. CT scan and MRI are needed to determine the sphenoidal bony defect and the relationship to the brain and meningeal coverings.

This photograph shows an infant with epignathus. Endotracheal intubation was essential to maintain the airway. (From TL Tewfik, VM Der Kaloustian, eds. Congenital Anomalies of the Ear, Nose and Throat, New York: Oxford UP; 1997, with permission).

This photograph shows an infant with epignathus. Endotracheal intubation was essential to maintain the airway. (From TL Tewfik, VM Der Kaloustian, eds. Congenital Anomalies of the Ear, Nose and Throat, New York: Oxford UP; 1997, with permission).

This plain radiograph of the epignathus in Picture 7 depicts bone and teeth formation. (From TL Tewfik, VM Der Kaloustian, eds. Congenital Anomalies of the Ear, Nose and Throat, New York: Oxford UP; 1997, with permission).

This plain radiograph of the epignathus in Picture 7 depicts bone and teeth formation. (From TL Tewfik, VM Der Kaloustian, eds. Congenital Anomalies of the Ear, Nose and Throat, New York: Oxford UP; 1997, with permission).

Most nasopharyngeal teratomas have no intracranial connections, and they are excised through a transoral approach. The nasopharyngeal component is typically removed easily because of the usual presence of cleft palate. If an intracranial component exists, a craniofacial approach is necessary. Prognosis is usually good, and malignant transformation has not been reported. [17]

The ex utero intrapartum treatment (EXIT) procedure is a new technique that establishes the fetal airway while uteroplacental circulation is still maintained. [18]

-

A patient with a congenital nasal dermoid.

-

A patient with encephalocele.

-

This MRI depicts a dermoid. The dermoid is intracranial but separate from the brain. (From TL Tewfik, VM Der Kaloustian, eds. Congenital Anomalies of the Ear, Nose and Throat. New York: Oxford UP; 1997, with permission).

-

CT scan demonstrating encephalocele.

-

The photograph shows a child with median nasal cleft. Note the marked hypertelorism and pronounced separation of the nostrils.

-

The photograph shows an infant with arhinia. (From Navarro-Vila et al, J Craniomaxillofac Surg 19:56, 1991, with permission).

-

This photograph shows an infant with epignathus. Endotracheal intubation was essential to maintain the airway. (From TL Tewfik, VM Der Kaloustian, eds. Congenital Anomalies of the Ear, Nose and Throat, New York: Oxford UP; 1997, with permission).

-

This plain radiograph of the epignathus in Picture 7 depicts bone and teeth formation. (From TL Tewfik, VM Der Kaloustian, eds. Congenital Anomalies of the Ear, Nose and Throat, New York: Oxford UP; 1997, with permission).

-

This drawing shows soft tissue clefts in the Tessier classification system.

-

This drawing shows bone clefts in the Tessier classification system.