Practice Essentials

Presentation with metastatic cervical lymphadenopathy is not uncommon for patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. In most cases, a thorough head and neck examination and various imaging modalities determine the primary site (origin) of the cancer. When clinicians are unable to determine the origin of the metastatic cervical lymphadenopathy, the cancer is said to originate from an unknown primary site. [1] Fine-needle aspiration is the main diagnostic procedure in the workup of occult primary tumors of the head and neck, with panendoscopy being the primary surgical therapy used to discover an occult primary lesion. (See the image below.)

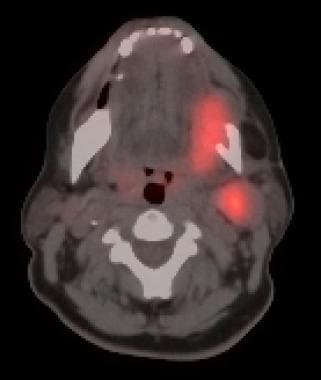

Computed tomography (CT)/positron emission tomography (PET) fusion; areas of uptake on the PET scan are mapped to the CT scan, and this image depicts the primary lesion in the left floor of mouth with metastatic disease to level II.

Computed tomography (CT)/positron emission tomography (PET) fusion; areas of uptake on the PET scan are mapped to the CT scan, and this image depicts the primary lesion in the left floor of mouth with metastatic disease to level II.

Signs and symptoms

Depending on where the primary cancer is based, signs and symptoms vary, as follows:

-

Otalgia/aural fullness - Pharynx, larynx, nasopharynx, or ear

-

Dysphagia/odynophagia - Pharynx, esophagus, or oral cavity

-

Hoarseness - Larynx

-

Trismus, dysarthria - Oral cavity or oropharynx

-

Nasal congestion, epistaxis - Sinonasal tract

-

Aspiration - Oropharynx or larynx

Workup

Per anesthesia guidelines, routine labs (electrocardiogram [ECG], chemistries, complete blood count [CBC], chest radiography) should be obtained in preparation for a panendoscopy and possible neck dissection in the operating room. Chemistries (eg, liver function tests [LFTs]) may also help to diagnose distant metastatic disease and to aid in the complete workup of staging the disease (TNM system).

Imaging studies include chest radiography (to screen for lung metastases) and computed tomography (CT) scanning of the head and neck with intravenous contrast (to evaluate cervical lymphadenopathy and identify occult primary lesions).

Fine-needle aspiration is the main diagnostic procedure in the workup of occult primary tumors of the head and neck. It is used to obtain a histologic diagnosis of the presenting neck mass.

Management

Panendoscopy is the primary surgical therapy used to discover an occult primary lesion.

Medical therapy is employed in patients without an identifiable primary lesion of the head and neck after a thorough examination of the head and neck, a panendoscopy, and possible neck dissection. Although the value of radiation therapy has been confirmed, the field to be covered by the treatment is controversial. Chemotherapy is generally reserved for patients with clinical or pathologic indicators of aggressive disease or primary nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Aggressive medical management consisting of both chemotherapy and radiation is reserved for advanced disease in patients who are deemed poor candidates for surgery or inoperable or in whom palliation is employed.

Problem

When the primary site of the carcinoma is known, clinicians are able to administer focused therapy to the primary site and cervical lymphadenopathy. Without this knowledge, clinicians are obligated to treat the entire pharyngeal axis and larynx to cover the possible origins of the metastatic carcinoma. The occult primary treatment regimen results in a significant increase in morbidity, predominantly due to radiation and chemotherapy.

Epidemiology

Frequency

Cancers with no known primary lesion site represent a heterogeneous group of malignancies that have been estimated to account for 0.5–10% of all tumors. Patients with cervical lymph node metastases represent a significant fraction of these cases. Data suggest that unknown primary carcinoma presenting as cervical lymph node metastasis accounts for approximately 2-9% of all head and neck malignancies. Approximately 90% of these neoplasms are squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), with the remainder being adenocarcinoma, melanoma, and other rare histologic variants. [2]

Etiology

The etiology of metastatic squamous cell carcinoma depends on the potential site of the unknown primary cancer. [3, 4]

-

Upper aerodigestive tract

Alcohol

Tobacco products

Betel nut

Plummer-Vinson syndrome

Potential risk factors -Human papillomavirus, poor oral hygiene, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and malnutrition

-

Nasopharynx

Environmental factors - Nitrosamines, polycyclic hydrocarbons, wood dust, and nickel exposure

-

Sinonasal - Nickel, wood dust, and thorotrast exposure

-

Cutaneous

Ultraviolet light exposure

Genetic disorder xeroderma pigmentosum (autosomal recessive)

Pathophysiology

The origin of the occult primary squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck is most likely the exposure of mucosa or skin to carcinogens that initially results in genetic mutations and eventually leads to invasive carcinoma (see the Etiology section).

In 1983, Syrjanen et al first proposed the participation of human papillomavirus (HPV) in oral and oropharyngeal carcinogenesis. A meta-analysis was later done to compare HPV in biopsies of oral squamous cell carcinoma with all head and neck squamous cell carcinoma biopsies, underscoring the relevance of viral oncogenes in the pathogenesis of this disease. [5, 6]

The pathophysiology of the unknown primary carcinoma is the same as that of known carcinoma of the head and neck. However, the occult primary carcinoma either metastasizes early to the cervical lymphatics or develops in an anatomic site that is not detectable with endoscopy or imaging techniques until it is of considerable size (T3, T4).

Presentation

The typical presentation of an unknown primary cancer of the head and neck is a complaint of a painless neck mass. According to the patient, the neck mass has usually been present for weeks to months.

History

A thorough history is obtained. The history should focus on questions regarding the presence or absence of the symptoms (see Table), and this can help direct the clinician in the search for the unknown primary cancer.

Table. Possible Source of Unknown Primary Cancer Based on Symptoms (Open Table in a new window)

Symptom |

Possible Source |

Otalgia/aural fullness |

Pharynx, larynx, nasopharynx, or ear |

Dysphagia/odynophagia |

Pharynx, esophagus, or oral cavity |

Hoarseness |

Larynx |

Trismus, dysarthria |

Oral cavity or oropharynx |

Nasal congestion, epistaxis |

Sinonasal tract |

Aspiration |

Oropharynx or larynx |

A social history should include occupational hazards (eg, exposure to ultraviolet light, industrial chemicals, or metals). Information concerning alcohol consumption and tobacco product usage should be obtained. The patient's country of origin is important for increasing a clinician's awareness of a possible occult nasopharyngeal carcinoma. The incidence of nasopharyngeal carcinoma is significantly increased in persons from China (particularly the Kwantung province and Hong Kong). An increased incidence also exists in patients from North Africa.

Physical

The physical examination should focus on the head and neck, beginning with inspection and palpation of the skin. Inspect the scalp and the external ears in detail, noting any abnormal skin lesions. Next, inspect and palpate the neck. Thoroughly palpate all zones of the neck in an effort to find additional lymphadenopathy or masses. The size of the neck mass, fixation of the overlying skin or underlying structures, the location of the mass in relation to relevant structures (eg, mandible, great vessels), and the presence or absence of bilateral lymphadenopathy can then be determined. Thoroughly inspect the nasal vestibule and the oral cavity/oropharynx. Because submucosal lesions are not typically evident with visual inspection, manual palpation of the oral cavity and the oropharynx is essential to a complete head and neck examination. Pay special attention to the base of the tongue during palpation because it is often a site of a submucosal occult primary cancer.

Because of the advances of fiberoptic technology and the easy access to fiberoptic nasopharyngoscopes, no physical examination of the head and neck is complete without their use. After topical anesthesia of the nasopharyngeal mucosa, the flexible nasopharyngoscope allows quick and easy access to the nasal cavities, the nasopharynx, the oropharynx, the hypopharynx, and the glottis. Make note of any mucosal lesions or suspicious areas. In the hands of an experienced practitioner, mirror examination of the nasopharynx, the base of the tongue, and the hypopharynx can be useful and revealing. When accessible, a biopsy should be performed on any suspicious lesions in the office.

A complete physical examination of the head and neck must include an examination of the cranial nerves. Any deficits should be noted and can be used to determine the extent of the neck disease and, possibly, the site of an occult primary cancer. [7, 8]

Indications

After documentation of metastatic squamous cell carcinoma lymphadenopathy and confirmation of the absence of any obvious primary tumor of the head and neck, the physician is obligated to perform a panendoscopy of the upper aerodigestive tract. Biopsy samples should be obtained from high-yield anatomic sites (nasopharynx, tonsils, pyriform sinus, hypopharynx, postcricoid area, the base of the tongue) and any other suspicious areas. The best opportunity to find the primary tumor is at the initial examination of the head and neck in the office. Surgical treatment of cervical lymphadenopathy in certain clinical situations may be performed at the same time as the panendoscopy. [9]

Relevant Anatomy

Knowledge of the levels of the lymph nodes in the neck with most common metastatic disease presentation helps the otolaryngologist tailor the search for the unknown primary. [10, 11]

-

Occipital nodes are responsible for drainage of the posterior scalp, which is posterior to an imaginary anatomic line drawn across the scalp that connects tragal cartilage to tragal cartilage.

-

Postauricular nodes are responsible for the lymphatic drainage of the posterior scalp, the mastoid, and the posterior auricle.

-

Parotid nodes are divided into extraglandular and intraglandular nodes. The extraglandular nodes are responsible for drainage of the anterior scalp (anterior to the aforementioned imaginary anatomic line). The intraglandular nodes are found in the parenchyma of the parotid gland and are responsible for the same anatomic regions as the extraglandular nodes and the parotid gland.

-

Retropharyngeal nodes are responsible for lymphatic drainage of the posterior region of the nasal cavity, the sphenoid and ethmoid sinuses, the hard and soft palate, the nasopharynx, and the posterior pharyngeal wall.

Level IA: The centrally located submental lymph nodes drain the mentum, the middle two thirds of the lower lip, the anterior gingiva, and the anterior tongue. The boundaries of this triangle are the anterior bellies of the digastric muscle and the hyoid bone.

Level IB: The submandibular nodes drain the ipsilateral lower and upper lip, the cheek, the nose, the medial canthus, and the oral cavity up to the anterior tonsillar pillar. The boundaries are the body of the mandible and the anterior and posterior bellies of the digastric muscle.

Levels IIA and IIB: These upper jugular nodes are located along the superior third of the sternocleidomastoid (SCM). Anteriorly, it is bounded by the stylohyoid muscle, and the posterior boundary is the posterior portion of the SCM. Inferiorly, its limit is a horizontal plane through the inferior body of the hyoid bone. The dividing line between the 2 sublevels of level II is the spinal accessory nerve (CN XI). Anything posterior to CN XI is level IIB, and the area anterior to CN XI is level IIA. Level II typically drains the oral cavity, nasal cavity, nasopharynx, oropharynx, hypopharynx, larynx, and parotid gland. Statistically, level IIB is more at risk of receiving metastatic disease from the oropharynx, while level IIA typically harbors metastatic disease from the oral cavity and larynx.

Level III: The middle jugular nodes are found along the middle third of the SCM. Its superior boundary is the horizontal plane through the inferior portion of the body of the hyoid, and its inferior limit is the horizontal plane through the inferior portion of the cricoid. It extends anteriorly to the sternohyoid and posteriorly to the posterior border of the SCM. This area typically drains disease from the oral cavity, oropharynx, nasopharynx, hypopharynx, and larynx.

Level IV: The lower jugular nodes are located along the inferior third of the SCM. The defined area extends superiorly from the horizontal plane through the inferior border of the cricoid to the clavicle inferiorly. Like levels II and III, the anterior border is the sternohyoid, and the posterior margin is the posterior border of the SCM. These lymph nodes likely have disease from the hypopharynx, thyroid, cervical esophagus, and larynx.

Levels VA and VB: The posterior triangle nodes are found in a large region bounded superiorly by the junction of the SCM and trapezius, inferiorly by the clavicle, anteriorly by the posterior border of the SCM, and posteriorly by the anterior border of the trapezius. A horizontal line through the inferior border of the cricoid divides the area into VA and VB. Level VA is superior and contains the spinal accessory nodes. Level VB is inferior and contains the nodes along the transverse cervical blood vessels and the supraclavicular nodes. Level V typically contains disease that drains from the nasopharynx, oropharynx, and the skin of the posterior scalp and neck. Disease in level VB with aerodigestive tract malignant features is a poor prognostic sign, and disease from the abdomen should be considered.

Level VI: The anterior or central compartment includes the pretracheal nodes, paratracheal nodes, perithyroidal nodes, and the precricoid (Delphian) node. This area extends superiorly to the hyoid bone, inferiorly to the suprasternal notch, and laterally to the bilateral common carotid arteries. Disease from the thyroid gland, glottic and subglottic larynx, apex of the pyriform sinus, and the cervical esophagus drains here.

Armed with the knowledge of various lymphatic drainage patterns and the nodal levels, the clinician can focus on the laterality of the neck mass. Knowing if a lesion is unilateral or bilateral can help guide the examining clinician. If the neck mass is unilateral, the primary lesion should be sought in ipsilateral mucosal or cutaneous sites (eg, tonsil, scalp). If the neck mass is bilateral, the occult primary lesion is likely from a midline structure (eg, base of tongue, supraglottis, nasopharynx). The other explanation of bilateral cervical lymphadenopathy is a laterally based lesion that extends past the midline.

The site of the metastatic lymphadenopathy can also be useful information for the clinician. For example, when the lymphadenopathy is located in the supraclavicular space, the lower deep lateral cervical chain, or the lower posterior triangle, the primary lesion is often not from the upper aerodigestive tract. The clinician should broaden the search for the primary lesion based on the pathology (eg, adenocarcinoma is suggestive of lung neoplasm). [12]

Contraindications

Contraindications to panendoscopy center on the initial workup that points to possible primary sites other than the upper aerodigestive tract (eg, supraclavicular lymphadenopathy with a lesion on the chest radiograph). In this scenario, the patient is better served by a further primary pulmonary neoplasm workup. If the clinical scenario is consistent with an occult primary malignancy of the head and neck, the clinician must complete the workup by performing a panendoscopy with biopsies.

-

Computed tomography (CT) scan of neck with contrast. The arrows indicate metastatic lymphadenopathy. Image courtesy of Head and Neck Cancer-Multidisciplinary Approach, Davidson, BJ.

-

Computed tomography (CT)/positron emission tomography (PET) fusion; areas of uptake on the PET scan are mapped to the CT scan, and this image depicts the primary lesion in the left floor of mouth with metastatic disease to level II.

-

Histologic appearance of metastatic squamous cell carcinoma. Image courtesy of Atlas of Head and Neck Pathology, Wenig, BM.