Practice Essentials

Tinnitus is the perception of sound in the head or the ears. The term tinnitus derives from the Latin word tinnire, meaning to ring. Typically, an individual perceives the sound in the absence of outside sounds, and the perception is unrelated to any external source. Sound that only the patient hears is subjective tinnitus, while sound that others can hear as well is called objective tinnitus.

Many people experience tinnitus after exposure to a gunshot or a loud concert with modern amplification. This type of tinnitus can be annoying, but it usually resolves in a matter of hours. Tinnitus is a symptom (not a disease) and therefore reflects an underlying abnormality. Most often, tinnitus is associated with a sensorineural hearing loss, but tinnitus types such as pulsatile tinnitus, tinnitus with vertigo, fluctuating tinnitus, or unilateral tinnitus should be investigated thoroughly. [1]

Estimates of patients with tinnitus range from 10-15% of the population (30-40 million people). Of patients presenting with ear-related symptoms, 85% report experiencing tinnitus as well. Both adults and children report experiencing tinnitus. Development of tinnitus increases in incidence with age, although the rate of tinnitus in children has been reported as high as 13%.

A study by Jarach et al estimated that worldwide, more than 740 million adults have experienced at least one tinnitus symptom, with more than 120 million determining their tinnitus to be a major problem. [2, 3]

Surveying adults in 12 countries of the European Union, Biswas et al found the estimated prevalence of tinnitus to be 14.7%. Ireland had the lowest rate, at 8.7%, and Bulgaria, the highest, at 28.3%. The prevalence of tinnitus in women was found to be 15.2%, compared with 14.0% in men. Increased age and reduced hearing status were associated with greater tinnitus prevalence. The odds of tinnitus occurrence were significantly greater in Northern European countries than in Western ones, the odds ratio (OR) for Western nations being 0.69. [4]

Workup in tinnitus

Each patient with the symptom of tinnitus deserves complete audiologic testing with pure-tone air, bone, and speech discrimination scores. Both pitch and loudness matching should be assessed. Minimum masking levels should also be obtained if treatment with ear-level devices is being considered.

Blood tests for syphilis (a fluorescent treponemal antibody-absorption [FTA-ABS]), a complete blood count (CBC), an autoimmune panel (antinuclear antibodies [ANAs], sedimentation rate, rheumatoid factor), and thyroid function tests for hypermetabolism may be useful.

Imaging studies include the following:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) - In pulsatile tinnitus, may be needed to look for a glomus tumor, arteriovenous malformations, vascular anomalies, dural arteriovenous fistulas, and aneurysms of the carotid in the ear; for asymmetrical hearing loss or unilateral tinnitus, MRI of the internal auditory canals is indicated to look for an acoustic tumor

-

Computed tomography (CT) scanning - Will delineate a sigmoid sinus diverticulum or bony dehiscence over the jugular bulb

Management of tinnitus

Treatments for tinnitus, which include the following, have met with differing success:

-

Electric stimulation

-

Biofeedback

-

Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation

-

Neuromonics

-

Counseling

-

Support groups

-

Pharmacologic therapy

-

Tinnitus maskers

-

Hearing aids

-

Tinnitus feedback retraining

Although tinnitus is not a surgical disease for the most part, tinnitus due to a surgical lesion in the ear usually responds to treatment of that lesion. Typical lesions amenable to surgery include those caused by glomus tumors, sigmoid sinus diverticulum, arteriovenous malformation, and conductive hearing loss.

Philosophy, Classification, Pathophysiology, and Quantification

Philosophy

Most of the knowledge and therapeutic options available to those who experience tinnitus have been encapsulated above. Individuals have placed advertisements in major otolaryngology, audiology, and neurology journals seeking therapeutic help. Such advertisements have yielded a great deal of interest but little substantive therapy. Unfortunately, because so little is known about the causes of tinnitus, little therapy is available to eliminate the problem. Frequently, therapy that is helpful to one person is not helpful to the next. Thus, many have adopted the philosophical outlook that tinnitus is a chronic or psychologic disease and is managed and not cured.

That philosophic approach to the problem of chronic tinnitus is apparent throughout this discussion of tinnitus. Because so few patients are cured, the emphasis should be on helping each individual cope with what is likely to be a chronic problem. As always, areas of active research are focused on developing a better understanding and therapy of tinnitus, and these are of importance for those interested in academic or investigative pursuits.

Such investigations have recently focused around the quantification of tinnitus, the medical and legal aspects of the problem, and the source of tinnitus. Many of these treatments are pioneered by a dedicated few. Most are described in a journal committed to the investigation, understanding, and treatment of tinnitus.

Classification

Tinnitus is classified in many cases into 2 categories. Tinnitus is either objective (ie, audible to anyone in addition to the affected individual) or subjective (ie, audible only to the affected individual). Even though this classification system is used quite frequently, focusing on the etiology of tinnitus is often more useful. The classification is discussed, and then this article focuses primarily on the various etiologies of tinnitus and their respective therapies.

Objective tinnitus is relatively rare. It is sound created somewhere in the body, usually in the ear, head, or neck, and has a muscular or vascular etiology. Muscular tinnitus is observed in several degenerative diseases of the head and neck, including amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. In this entity, the neuromuscular control over the muscles in the ear occasionally deteriorates in an individual with perfect sensory perception. Occasionally, the loss of control results in a repetitive flutter or myoclonus of either the stapedius or tensor tympani muscles. The result is an observable and audible flutter coming from the ear.

Lysis of the tensor or stapedius muscle via a tympanotomy incision is uniformly successful in relieving the symptoms in these cases. However, attention must be paid to the contralateral side. Often, the problem is bilateral, but attention is directed to the louder side. If in fact contralateral problems are present, both muscles should be cut at the same time. This is one of the few cases in otology where operating on both sides at the same time may be considered, decreasing the anesthesia risk and attendant logistic problems for the patient who frequently has problems with anxiety.

Palatal myoclonus is a rare cause of muscular-induced clicking tinnitus. It results from rhythmic discharges from the inferior olivary nucleus by a lesion in the triangle of the Guillain-Mollaret (brainstem). The lesion is usually due to stroke, trauma, encephalitis, multiple sclerosis (MS), or degenerative disease. Some success has been reported with botulinum toxin injection therapy.

The other disturbance that is more frequently observed is an aberrance or abnormality of the carotid artery. Aberrances of the carotid artery are documented multiple times in the literature. The carotid artery can also become ectatic as a person ages or as operations are performed on the carotid. The end result is an artery that often takes a tortuous route through the neck and the ear to reach the brain. Such tortuosity produces turbulent flow in the artery, which can be auscultated by the examiner with each heartbeat.

Similarly, the jugular bulb and the jugular vein can produce a type of tinnitus that is characterized as a venous hum. Often described by the patient as a vibration or a low-pitched sound rather than as a ringing, these sounds seem to be slightly more frequent than the other 2 types of objective tinnitus. Many operations have been described for the treatment of venous hum tinnitus and carotid arterial tinnitus; all of these operations have initially met with success but limited long-term control of the symptom.

Tinnitus pathophysiology

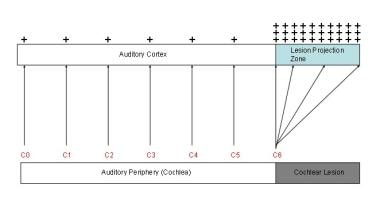

Clinically, subjective tinnitus is the perception of sound in the absence of auditory stimulation. In terms of neurophysiology, tinnitus is the consequence of the brain’s response to input deprivation from the auditory periphery. In the healthy auditory system, there is an ordered tonotopic frequency mapping from the auditory periphery (cochlea), through the midbrain, to the auditory cortex. When a region of the cochlea is damaged, the subcortical and cortical projections adjust to this chronic lack of output (plasticity), and the tonotopic organization is altered. In the auditory cortex, the region that corresponds to the area of cochlear damage is termed the lesion projection zone (LPZ). After cochlear damage, neurons in the LPZ show 2 important changes: an increase in the spontaneous firing rate and an increase in the frequency representation of the neurons that border the region of damage (the so-called lesion edge frequencies).

Tinnitus model. Two phenomena in the auditory cortex are associated with peripheral deafferentation: 1) hyperactivity in the lesion projection zone and 2) increased cortical representation of the lesion-edge frequencies (here, C6) in the lesion projection zone. These two phenomena are presumed to be the neurophysiological correlates of tinnitus. The red letters correspond to octave intervals of a fundamental frequency.

Tinnitus model. Two phenomena in the auditory cortex are associated with peripheral deafferentation: 1) hyperactivity in the lesion projection zone and 2) increased cortical representation of the lesion-edge frequencies (here, C6) in the lesion projection zone. These two phenomena are presumed to be the neurophysiological correlates of tinnitus. The red letters correspond to octave intervals of a fundamental frequency.

These findings are explained in terms of a) the loss of central inhibition on the regions that are damaged and b) cortical plasticity of the neighboring regions of the cortex that are still active. Hence, tinnitus neurophysiology is related to detrimental cortical adaptation to input deprivation from the sensory periphery.

Additional data from animal and human studies have suggested that tinnitus may be associated with neuronal hyperactivity at different levels of the central auditory pathways, including the dorsal cochlear nucleus, the inferior colliculus, auditory cortex, and the striatum.

A literature review by Tegg-Quinn et al indicated that tinnitus can cause cognitive difficulties in adults by affecting executive control of attention. [5] A prospective study by Gudwani et al also suggested that an association exists between tinnitus and cognitive problems. The report, which involved 25 patients, indicated that chronic, subjective tinnitus has a particularly deleterious effect on digit-span tests, verbal comprehension, mental balance, attention and concentration, immediate recall, visual recognition, and visual-motor gestalt tests. [6]

There is evidence, albeit perhaps limited, that tinnitus may be associated with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). A literature review by Almufarrij and Munro suggested that the prevalence of tinnitus, hearing loss, and rotatory vertigo in individuals who have had COVID-19 is 14.8%, 7.6%, and 7.2%, respectively. However, the investigators state that there has been a lack of high-quality, control-based studies on the audio-vestibular effects of COVID-19. [7]

Evidence also exists that tinnitus may develop in rare cases following immunization with vector-based or mRNA COVID-19 vaccines. By September 14, 2021, the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS) of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) had received reports of 12,247 cases of tinnitus that developed after COVID-19 vaccination. An article published in early March 2022 by MedPage Today reported that a search of the VAERS database turned up over 13,000 results for the occurrence of tinnitus following the use of mRNA COVID-19 vaccine. Although it is not known how vaccination against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the virus that causes COVID-19, may be linked to tinnitus, researchers have suggested that cross-reactivity may exist between anti-spike SARS-CoV-2 antibodies and otologic antigens, producing inflammation. [8, 9, 10]

Measurement and quantification

Volumes are devoted to the quantification and measurement of tinnitus. One of the more successful and useful mechanisms for the quantification of tinnitus has been the matching of tinnitus to a tone presented to the patient in a sound-treated room, using an audiometer. Such procedures, types of tinnitus matching, are used to provide a measure of tinnitus for reevaluation of symptoms before, during, and after therapy. Although those who experience tinnitus often describe their match as exact, they quickly point out that such a match does not adequately reflect the severity of the problem affecting their daily lives.

For excellent patient education resources, visit eMedicineHealth's Ear, Nose, and Throat Center. Also, see eMedicineHealth's patient education article Tinnitus.

Evaluation: History, Physical, and Laboratory

Because of the vast array of potential diagnoses related to tinnitus, each patient requires a thorough history and physical evaluation. Such an evaluation requires attention to detail, including all medical problems and associated treatments and any pharmacologic therapy. The otolaryngologist is required to expand the evaluation to include the other potential sites of difficulty in this case. Evaluation of tinnitus should begin with a very thorough history, physical examination, and indicated laboratory tests. With tinnitus, direct particular attention to the patient's psychological state. Many patients are depressed or very anxious about the problem. Therefore, the use of various psychological evaluation techniques is required.

History

The goal is to discover the underlying problem that has led to tinnitus. The time course of many cases of tinnitus points toward a labyrinthine source. Details may be obscured by the number of factors that have occurred since the origin of the tinnitus. Further, the detail-oriented individual insists that many issues may have related to the tinnitus. The examiner may be overwhelmed with such details.

Because most cases of tinnitus are related to hearing loss, questions attempt to determine the presence, development, time course, and severity of any hearing loss. The presence of vertigo, otalgia, otorrhea, or temporomandibular joint (TMJ) disease can relate to tinnitus, with a Korean study finding, after adjustment for covariates, that tinnitus was 1.6 times more common in individuals with TMJ disease than in those without it. In addition, the investigators determined that tinnitus was also more prevalent in persons with dental pain (21.1%), with the rate being 22.5% in those with TMJ disease, 31.2% in those with a combination of dental pain and TMJ disorder, and 19.6% in individuals with neither dental pain nor TMJ disease. [11] Thus, minor details that would be cursory in other cases may lead to vital answers to the problems associated with tinnitus.

Many modern prescription and over-the-counter drugs can be a major source of tinnitus, creating or exacerbating the condition. Aspirin or aspirin-containing compounds (in sufficient amounts) often cause tinnitus. Patients vary in their tolerance to the aspirin-containing compounds. Aspirin is often found in small amounts in other drugs as well. In some individuals, 3000 mg of aspirin may produce tinnitus, but this same amount may not affect another person.

Tinnitus is one of the side effects of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in nearly every case. However, as with aspirin, this effect seems to be dose related. Diuretics (eg, ethacrynic acid, furosemide) may also produce a dose-related tinnitus. This particular effect may be reversible with these drugs, but it may be permanent in others. Permanent hearing loss and accompanying tinnitus is frequently observed with ototoxic chemotherapeutic agents such as the various platinum compounds. The American Tinnitus Association (ATA) distributes an extensive list of medications associated with tinnitus. The exact cause of the tinnitus in these pharmacologic etiologies remains obscure.

One of the primary goals of this initial history is to exclude any causes of tinnitus that may be life threatening. Pulsatile or unilateral tinnitus suggests the possibility of a glomus or cerebellopontine angle tumor. [12] Although many of these are vascular in nature and may be audible by the examiner, most are not and, thus, are audible only to the patient. Fluctuating tinnitus, tinnitus accompanied by dizziness, or dizziness and hearing loss may suggest Ménière disease.

In a study of the comorbidities and sequelae of tinnitus in adults, Bhatt et al found a close association between tinnitus and anxiety, depression, fewer hours of sleep, and a higher number of missed workdays. According to the study, 26.1% of adults with tinnitus reported anxiety problems within the previous 12 months, compared with 9.2% of persons without tinnitus. Depression was reported by 25.6% of individuals with tinnitus, compared with 9.1% of adults without it. [13]

A study by Kim et al of 19,290 adults (from the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey) found a prevalence of tinnitus of 20.7% in this population and a greater adjusted odds ratio for the condition in persons with a history of the following [14] :

-

Smoking

-

Reduced sleep (≤ 6 h)

-

Stress

-

Hyperlipidemia

-

Osteoarthritis

-

Rheumatoid arthritis

-

Asthma

-

Depression

-

Thyroid disease

-

Tympanic membrane abnormality

-

Unilateral or bilateral hearing loss

-

Noise exposure from earphones

-

Noise exposure in or outside of the workplace

-

Brief noise exposure

Women, unemployed individuals, soldiers, and persons living in smaller households also had a greater prevalence of tinnitus. A literature review by Yang et al suggested that hypertension may be a risk factor for tinnitus, with the pooled odds ratio found to be 1.37. [15]

A report by Loiselle et al, consisting of a clinic-based, cross-sectional questionnaire study and a population-based, cross-sectional study, indicated that persons with glaucoma are more likely to also have tinnitus. The clinical study found an 85% greater likelihood of tinnitus in glaucoma patients, while according to the population-based study, the odds for the existence of tinnitus were 19% greater in the presence of glaucoma. The investigators suggested that a common mechanism, possibly “vascular dysregulation due to impairment of nitric oxide production,” could be involved in glaucoma and tinnitus. [16]

A study by Qian and Alyono, using the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (2011-2012), indicated that regular marijuana use may be linked to prevalent tinnitus. The investigators found the odds ratio for prevalent tinnitus among persons who had used marijuana at least once per month during the previous 12-month period to be 1.75, after covariables such as age, gender, audiometric hearing loss, noise exposure history, depression, anxiety, smoking, salicylate use, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, and diabetes had been taken into account. However, no association was found between tinnitus and alcohol, cocaine, methamphetamine, or heroin use. The report suggested that psychosocial factors modulate the marijuana/tinnitus relationship. [17]

Because tinnitus is associated with depression, seek signs of the condition. A careful assessment of the mental status of patients is an essential part of the initial history. The Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Index can be useful, but it is time consuming and requires professional interpretation. The common associated symptoms of early morning awakening and sleeplessness may be helpful. Other criteria can be used from the current Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM). A useful adjunct to patient history is the Beck Depression Inventory. A score of 8 or more on the inventory indicates a need for further evaluation.

The Tinnitus Handicap Inventory (THI) is another measure; it was validated and reported in 1996. [18] Use of this instrument is helpful in the quantification of tinnitus and how it affects daily living. The questionnaire can be used at diagnosis and during treatment and follow-up to measure progress. This allows caregivers to better understand how incapacitating the disease process may be and to help in treatment planning.

Physical examination

The physical examination includes not just the ear but also the entire head, neck, and torso for signs of the origin of tinnitus. Include complete auscultation of the neck for bruits, which can be transmitted along the carotid artery, and for venous hums, which can be transmitted along the jugular vein. Auscultation should also be performed around the cranium to check for arteriovenous malformations and Paget disease, which can in rare cases contribute to tinnitus. Be sure to clean the ear canal of wax (a frequent cause of tinnitus).

The examination may reveal other causal indications of tinnitus (eg, red hue of otosclerosis, bluish tint of an uncovered jugular vein). An otomicroscopic examination may assist in this portion of the examination. The tympanic membrane can be examined for fluid or infections, which can contribute to tinnitus.

Other tumors of the middle ear, including glomus tumors, can be observed. The Brown sign, a middle ear bluish-red mass that blanches with positive pressure during pneumatic otoscopy, is a well-mentioned sign of glomus, although not always present. A Toynbee tube (stethoscope with olive tip) or an electronic stethoscope can be used to listen to the ear for objective tinnitus. With glomus tumors, the pulsatile rush of blood in the tumor can be heard. Tuning forks can be used to assess hearing, prior to obtaining audiometric data.

Laboratory studies

Each patient with the symptom of tinnitus deserves complete audiologic testing with pure-tone air, bone, and speech discrimination scores. Order or perform these tests even if (as is common) the patient is unaware of hearing loss. During the audiometric evaluation, the audiologist can complete the subjective tinnitus matching evaluation to gain better understanding of the patient's symptom. Such thoroughness is often reassuring to the patient because the physician is taking the condition seriously.

Both pitch and loudness matching should be assessed. However, the examiner should remember that 90% of patients with tinnitus match their tinnitus at 20 dB or less and 84% match their tinnitus at 9 dB or less; thus, the reported severity of the condition may seem to be out of proportion to the measurement. Minimum masking levels should also be obtained if treatment with ear-level devices is being considered.

Other examinations may also be necessary. Blood tests for syphilis (a fluorescent treponemal antibody-absorption [FTA-ABS]), a complete blood count (CBC), an autoimmune panel (antinuclear antibodies [ANAs], sedimentation rate, rheumatoid factor), and thyroid function tests for hypermetabolism may be useful, but clinical signs may indicate this problem earlier.

Imaging studies

For pulsatile tinnitus, a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan with or without MR angiographic scanning may be needed to look for a glomus tumor, arteriovenous malformations, vascular anomalies, dural arteriovenous fistulas, and aneurysms of the carotid in the ear.

A computed tomography (CT) scan of the temporal bone will delineate a sigmoid sinus diverticulum or bony dehiscence over the jugular bulb. A hyperdynamic state, such as anemia, hyperthyroidism, or pregnancy, may cause a pulsatile tinnitus. For asymmetrical hearing loss or unilateral tinnitus, MRI of the internal auditory canals is indicated to look for an acoustic tumor.

Positron emission tomography (PET) scanning is currently being studied as a diagnositic aid in tinnitus management. PET scanning helps identify areas of enhanced neural activity. Therefore, it has been suggested that this can be used pretreatment and posttreatment to identify changes in neural activity. [19]

The American College of Radiology (ACR) has published appropriateness criteria on imaging in the assessment of tinnitus. [20]

Surgical Therapy

Although tinnitus is not a surgical disease for the most part, tinnitus due to a surgical lesion in the ear usually responds to treatment of that lesion. Typical lesions amenable to surgery include those caused by glomus tumors, sigmoid sinus diverticulum, arteriovenous malformation, and conductive hearing loss.

The examiner should suspect glomus tumors in any case of pulsatile tinnitus that corresponds to heartbeat. Pulsatile tinnitus resolves once the tumor is removed. However, the patient may still have a hum or other vascular symptom due to the surgery.

Similarly, most patients with acoustic tumors present with tinnitus. Once the tumor is removed, 50% find the tinnitus improved, and 50% find it to be unchanged. Additionally, dural arteriovenous fistulas can be embolized, and aneurysms can be clipped. When a jugular venous hum is diagnosed, the optimum therapy may be counseling and reassurance. Ligation of the vein or other arteriovenous malformation may resolve the symptom, but it frequently returns after a number of years.

A study by Wang et al indicated that in patients with pulsatile tinnitus caused by sigmoid sinus diverticulum (SSD), surgical correction of the SSD and of any accompanying sigmoid sinus wall dehiscence (SSWD) can effectively eliminate the tinnitus. The study involved 25 patients with SSD, most of whom also had SSWD, who underwent sigmoid sinus wall reconstruction. The investigators found that pulsatile tinnitus completely resolved in 17 patients and partially resolved in three of them. [21]

Tinnitus is organic to Ménière syndrome. Thus, treatment of the syndrome may help resolve tinnitus. In more severe cases, tinnitus may remain despite best efforts at treatment. Surgical intervention with an endolymphatic shunt, nerve section, or labyrinthectomy and ototoxic antibiotic injection provides relief for 40-80% of such patients. Interestingly, the recent advent of gentamicin or corticosteroids has resulted in a higher percentage of patients describing either temporary or permanent relief from tinnitus. The exact mechanism of relief is unknown, but relief is greatly appreciated by patients.

As discussed in the Philosophy section, the problem with the therapy of tinnitus is its unpredictability. Although the successful ablation of the identifiable problem in many of these cases should eliminate the problem, often only 50% of patients describe complete relief from the difficulty. The explanation seems to rest with some type of sensitization to the function of the inner ear, auditory nervous system, and the brain, with the resultant head noise, or tinnitus.

Medical and Otopsychiatric Therapy

Electrical stimulation

Suppression of tinnitus by electrical stimulation of the inner ear has met with mixed success since Volta attempted direct current (DC) stimulation of his inner ears in the 1800s. Many variations of electrical stimulation have been tried, including cutaneous stimulation, brain stimulation, promontory stimulation, an electrically stimulating headset, and others. Although the authors of these studies frequently report tinnitus resolution in as many as 80% of their patients, the effects are often transient or continued stimulation is impractical. Since the first single channel cochlear implants were available, the reduction of tinnitus has been an interesting topic. But even in the case of continuous electrical stimulation of the inner ear using cochlear implants, results have been mixed. Therefore, electrical stimulation has advocates, but it is not considered one of the primary mainstream therapies for tinnitus.

Biofeedback

This technique has a 25-year history of successful treatment for pain and other stress-related disorders. As described above, the patient's psychological state of mind may have more to do with the status of his tinnitus than the actual loudness of the tinnitus itself. With biofeedback in tinnitus, the goal is to decrease stress and anxiety levels that may be contributing to tinnitus. For biofeedback success, the patient must be cooperative and committed. The patient is taught to relax and is encouraged to relate his state of relaxation to the stress of living and the gradual reduction of the tinnitus. Therapy may require weekly sessions over several months to demonstrate improvement. A psychologist who can work as a team with the otologist to gain maximum benefit from the therapy conducts this therapy. Up to 80% of patients find some relief of their symptoms, and 20% of patients may find total relief in this therapy.

Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation

Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) is a method of stimulating the brain through the intact scalp without causing pain at the surface. It is a minimally invasive method for depolarizing cortical neurons and is based on the principle of electromagnetic induction. The rhythmic application of a series of single stimuli is referred to as repetitive TMS (rTMS), a method that has been demonstrated to induce long-term potentiation (LTP) or long-term depression (LTD)–like changes of cortical excitability that outlast the stimulation period. rTMS has been investigated as a therapeutic tool for depression, schizophrenia, and stroke. [22]

Tinnitus is considered by some to be a result of excitability of the cerebral cortex and, more specifically, the primary auditory cortex. rTMS has proven effective in the treatment of other disorders, such as auditory hallucinations, by modification of cerebral excitability.

Studies have indicated that the technique can alleviate tinnitus in the short-term by modulating the excitability of neurons in the auditory cortex, [23] and a report stated that the use of rTMS with neuronavigation imaging resulted in a reduction in tinnitus severity after 6 months of follow-up compared with sham therapy. [24] Further studies regarding the long-term clinical effectiveness of rTMS are required, although a literature review by Heiland et al reported that rTMS achieved significant tinnitus improvement in the long-term, lowering the THI score by 8.6 points. [25]

In a study of 40 patients with chronic tinnitus, either alone or with major depressive disorder (MDD), Berman et al found evidence that multilocus sequential rTMS can significantly improve tinnitus. Patients were first treated at the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and then the auditory cortex (Heschel gyrus). After five sessions, patients improved by a mean 6.8 points on the Tinnitus Functional Index (TFI), and after 10 sessions, by a mean 9.2 points. Forty-eight percent of patients had, within 10 sessions, responded to treatment, although those with comorbid MDD responded less well than did those with tinnitus alone, the improvements in the TFI being 4.3 points and 14.7 points, respectively. However, post hoc analyses suggested that after 30 sessions, patients with MDD experienced a degree of improvement similar to that of persons with tinnitus only. [26]

Neuromonics

Neuromonics tinnitus treatment uses spectrally modified music in an acoustic desensitization approach in order to help patients overcome the disturbing consequences of tinnitus. Studies have both supported and refuted its efficacy.

Counseling

Usually, patients simply want to know that their tinnitus is not caused by cancer or malignant brain tumor. A skilled counselor can easily provide this reassurance. For most patients, once more serious possibilities are eliminated, counseling suffices. Amplification with hearing aids or other devices may improve subjective tinnitus in more than 50% of patients. Occasionally, the professional services of a psychologist are necessary. The otolaryngologist should be prepared with a teammate who can assist in the care of more complicated tinnitus cases.

In a literature review, Phillips et al, looking at patients in the no-intervention or waiting-list control arm of tinnitus intervention studies, found that, in self-reported results, individuals experienced a small but significant improvement in tinnitus measures over time. Although the investigators could not specify the clinical significance of this, they indicated that the information can be cautiously employed in patient counseling. [27]

Support groups

People with tinnitus often feel alone with their condition. The opportunity to share experiences in a group session, either with or without a counselor, is helpful. Many cities have support groups that meet on an irregular basis. These groups can be found by calling the local public library or the newspaper for meeting times. Many otolaryngologists who care for large groups of tinnitus patients have assisted a local group through its formation and development.

American Tinnitus Association

The American Tinnitus Association (ATA), based in Portland, Oregon, is one of the best-known organizations providing sympathetic support. The organization directs research and education pertaining to tinnitus across the country. The ATA publishes a monthly newsletter that many patients find reassuring. They know that research is being conducted and that others in the world have similar symptoms.

Pharmacologic therapy

Pharmacologic therapy helps in the treatment of tinnitus for the 80% of patients who endure related depression. Administration of nortriptyline (50 mg at bedtime) is the most helpful treatment. Nortriptyline may induce dry mouth, often causing patients to terminate treatment before achieving therapeutic effect. Often, 3-4 weeks of therapy are necessary before benefits appear. Other antidepressants may be useful in treating tinnitus, but judgment in their use is paramount. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors are considered to have a better safety profile compared with tricyclic antidepressants. Paroxetine (Paxil) in low doses of 10 mg at bedtime has recently been shown to be helpful. Also, sertraline (Zoloft), at a fixed dose of 50 mg/d, demonstrated a significant reduction in tinnitus severity, as well as a reduction in anxiety and depressive symptoms.

Many physicians have used benzodiazepines to treat tinnitus. The theory has been that this is an anxiety disorder and the benzodiazepines should help. Unfortunately, because depression and obsessive-compulsive disorders predominate in this group, the benzodiazepines can cause more harm than good. Thus, they should be avoided as initial therapy.

A 2009 study by Jalali determined that alprazolam improved visual analog scale (VAS) scores in tinnitus patients who did not have depression or anxiety disorders. [28]

Hurtuk et al conducted a prospective, double-blind, cross-over study comparing 3 mg of melatonin HS to placebo in adults with chronic tinnitus. There was a significant reduction of tinnitus severity scores on 2 of 3 measures of tinnitus severity. Melatonin was more effective in men, subjects with severe tinnitus, and those who had not had prior treatment. [29]

A study by Albu and Chirtes indicated that combining an intratympanic corticosteroid with melatonin can improve treatment results in tinnitus over those obtained with melatonin therapy alone. In a prospective, randomized, controlled, double-blind trial, 30 patients with acute unilateral idiopathic tinnitus were treated with melatonin alone, while another 30 patients with the condition were treated with melatonin and intratympanic dexamethasone, with results after three months being evaluated using tinnitus loudness and awareness scores, the THI, the Beck Depression Inventory, and the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index. Although both groups in the study demonstrated significant improvement, the investigators determined that significantly greater improvement occurred in the dexamethasone/melatonin patients. [30]

N-methyl-d-aspartate

Drugs that increase synaptic inhibition, such as benzodiazepines and GABA-B receptor agonists, have been one avenue of investigation for potential new treatments for tinnitus. However, the mechanisms underlying the neuronal hyperactivity associated with tinnitus are not entirely understood, and drugs that block excitatory synaptic neurotransmission may also be effective. For example, some evidence suggests that salicylate-induced tinnitus may involve an increase in glutamatergic neurotransmission at the N -methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) subtype of glutamate receptor in the cochlea and that NMDA receptor antagonists can block this effect. Moreover, long-term tinnitus induced by acoustic trauma was prevented by locally applying another NMDA receptor, polyamine site, antagonist, ifenprodil, into the cochlea within the first 4 days after the acoustic trauma. [31]

Tinnitus maskers

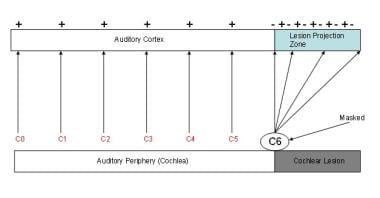

Tinnitus masking has been central to tinnitus therapy for over 50 years. From a psychoacoustic viewpoint, masking is an important tool in the clinical armamentarium because it relieves the percept of tinnitus, even if only transiently, when the masking noise is present. From a neurophysiology point of view, masking appears to act by relieving hyperactivity in the auditory cortex (and associated pathways) that accompanies peripheral deafferentation.

A literature review by Makar et al indicated that tinnitus is best treated with a combined approach incorporating masking, counseling, and attention diversion. [32]

Perhaps the most elegant treatment of the topic of masking is from the neuro-computational literature, where the phenomenon of ‘homeostatic plasticity’ is used to describe how the loss of peripheral afferents can cause central hyperactivity. Importantly, this literature explains the paradoxical finding that stimulation of the region of damage (ie, the lesion-edge frequencies) is the most efficient way to decrease this central hyperactivity.

Masking. In this graphic, masking sounds are applied at C6, the tinnitus frequency. The result is that the sensation of tinnitus is reduced. In the auditory cortex, this corresponds to decreased spontaneous firing rates.

Masking. In this graphic, masking sounds are applied at C6, the tinnitus frequency. The result is that the sensation of tinnitus is reduced. In the auditory cortex, this corresponds to decreased spontaneous firing rates.

These devices resemble hearing aids and fit either behind or in the ear. Tinnitus maskers create and deliver constant low-level white noise to the ear(s) of the patient. This device is recommended for patients with normal or near-normal hearing who are disturbed by the tinnitus. Patients should be advised to wear the device during their waking hours (successful wearers tend to wear the device even while sleeping). Of patients referred for a masker, two thirds investigate the possibility, one third rent the device, and one sixth actually wear the device for a time and find it helpful.

Many people are bothered most by tinnitus at bedtime. In these cases, a bedside clock or radio may serve as a useful masker. Such instruments fill the ambient silence with low-level noise that masks tinnitus. An obvious problem with maskers is that sound is masked from inside and outside the ear. Tinnitus maskers, therefore, may interfere with hearing and communication. However, patients have reported better hearing when their tinnitus was helped with the masker. Occasionally, a residual inhibition of tinnitus occurs, so patients can wear maskers at bedtime and still benefit from the effect when not wearing the device during the day.

Hearing aids

"If this tinnitus would stop, I could hear better!" is a common comment from patients with mild or moderate hearing loss. Patients often perceive no hearing loss and think that their tinnitus alone interferes with hearing. Improvement in the overall situation can be achieved by directing attention to the underlying problem (hearing loss). Characteristics of hearing loss have been studied and show no correlation with successful hearing aid use. Common sense suggests that residual inhibition characteristics of tinnitus and hearing loss determine which patients would be helped by hearing aids.

Unfortunately, such is not the case. The only way to determine if a hearing aid is successful is to try one. Success at treating tinnitus with hearing aids is about 50%. That is, about 50% of patients who try hearing aids are helped and are happy with the treatment. Many hearing aid dealers offer trial programs to determine suitability for individual patients. Studies demonstrate a benefit of ear-level devices (hearing aids and sound generators) in patients enrolled in comprehensive tinnitus management programs. [33] Patients who use hearing aids and sound generators show a greater improvement in their tinnitus severity index scores and self-rated tinnitus loudness.

Tinnitus feedback retraining

Recently, another type of therapy has been developed. White noise or a derivative of the patient's tinnitus that is chosen during a diagnostic session is programmed into a special hearing aid and worn in the ear. This therapy is accompanied by counseling sessions and continuing efforts to assist the patient in coping with the tinnitus. Such sessions may last for one hour once a week or once a month depending on the severity of the tinnitus. Patients occasionally use this therapy for periods of up to 1-2 years. The success with this therapy varies with the severity of the tinnitus and the patient's other problems.

One of the biggest factors in resistance to this therapy is the associated physiatric and emotional disorders. Recognition and treatment of these disorders are very helpful. One of the best ways to decide if this therapy is appropriate is to visit a therapy session and experience it firsthand. Therapists must regularly practice the regimen to do it well, and patients must use the therapy for a period of months to determine if it is useful. Long-term studies have shown that up to 82% of patients enrolled showed improvement in their subjective tinnitus. This method of treatment remains a valuable tool in the management of severe tinnitus.

Alternative Therapies

Alternative therapies have become a mainstay of many practitioners around the country. Individuals seek relief from problems that modern medicine may not provide. Tinnitus fits this description well. However, patients are often offered various therapeutic options without good controls or explanations as to why they may be effective. Moreover, because of the variability in the bioavailability of some of these drugs, the effects of the drugs may vary. Thus, a patient experiencing success may find that success lacking with the next lot of therapy that is purchased. The major difficulty in these therapies is obtaining therapeutic doses that are consistent from lot to lot and from manufacturer to manufacturer. Many suggest using these compounds to effect, that is, until the desired effect is achieved. Such use may be quite dangerous.

Ginkgo biloba

Leaves of the common ginkgo biloba tree provide the origin of this therapy. The tree is very old; its fossil record dates back 200 million years. The extract is created through a complicated process, but the result contains bioflavonoids and terpene lactones as active ingredients. The extract increases blood flow to the brain and small blood vessels by inhibiting platelet aggregation and by regulating blood vessel elasticity. Ginkgo biloba is also a powerful antioxidant. The proper treatment seems to be a combination of about 25% bioflavonoids and 6% terpene lactones at a dose of 80 mg 3 times a day. Effects may not be observed for up to 12 weeks, so therapy should continue for at least that long. Because ginkgo affects platelet aggregation, a bleeding time should be checked if ginkgo is used for more than 4 continuous weeks.

Niacin

Niacin has been used as therapy for tinnitus for years with variable success. Niacin is thought to provide smooth muscle relaxation and perhaps increased blood flow to tiny blood vessels supplying the inner ear. Patients often sustain a blush when taking niacin in effective doses. Forewarn patients of this effect because some can be frightened by the phenomenon. About half of all patients with tinnitus report successful treatment with niacin. Patients often report that niacin decreases the intensity or severity of tinnitus.

Combination supplements

Various combinations of vitamins or supplements are on the market for tinnitus. Most of these use a combination of antioxidant vitamins or supplements that have been shown to slow age-related hearing loss in animal studies and a few human studies. In addition, melatonin has been used to help with the patients’ insomnia. A combination of antioxidants and melatonin taken nightly may be of benefit in these patients.

Acupuncture

Acupuncture sites for treating tinnitus and other ear disorders abound near the ear (and elsewhere). Anecdotal patient accounts indicate that treatment of tinnitus by acupuncture is very effective. Data are accumulating about the success of acupuncture, but controlled studies suggest a strong component of faith in either the examiner or the treatment. Six studies were reviewed that were randomized and controlled; no significant difference was found between the treated and the controlled groups when the patients were blinded as to form of therapy. When the patients were not blinded, beneficial effect seemed to occur. This suggests, of course, that a strong placebo effect is present in acupuncture. As in most areas of alternative therapy, the belief of the patient and the treating individual in this form of care is a very strong component of the therapy.

Conclusion

Tinnitus is a symptom that requires further investigation to determine origin. Often, the origin may be a sensorineural hearing loss. Certain types of tinnitus signify other problems. Unilateral or pulsatile tinnitus and tinnitus associated with vertigo or conductive hearing losses are examples. Tinnitus therapy is as multifaceted as the origins of tinnitus. Choose therapy, therefore, with individual symptoms and problems in mind. A combination of sound-based therapy with medical therapy of anxiety, depression, or insomnia will help most patients. By applying the best of the multiplicity of available therapies, patients need never again hear the old adage, "you'll just have to live with it."

Guideline Summary

In 2014, the American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery Foundation (AAO-HNSF) released the first evidence-based clinical guidelines for the assessment and management of chronic tinnitus. The major recommendations include the following [34] :

-

Conditions that if promptly managed may relieve tinnitus should be identified during the initial evaluation of a patient with presumed primary tinnitus

-

Patients with tinnitus that is unilateral and associated with hearing difficulties or that persists for 6 months or more should undergo a comprehensive audiologic examination.

-

Imaging studies of the head and neck are not recommended specifically to evaluate tinnitus unless one or more of the following is present: tinnitus that localizes to 1 ear, pulsatile tinnitus, focal neurologic abnormalities, and/or asymmetrical hearing loss

-

Distinguish patients with bothersome tinnitus from those with nonbothersome tinnitus; educate patients with persistent, bothersome tinnitus about management strategies

-

Patients with hearing loss and persistent, bothersome tinnitus should be offered a hearing aid evaluation, sound therapy, and cognitive behavior therapy

-

Antidepressants, anticonvulsants, anxiolytics, or intratympanic medications should not be offered as a primary treatment for persistent, bothersome tinnitus

-

Ginkgo biloba, melatonin, zinc, or other dietary supplements or transcranial magnetic stimulation should not be recommended for treating patients with persistent, bothersome tinnitus

Questions & Answers

Overview

Which clinical history findings are characteristic of tinnitus?

What are possible risk factors for developing tinnitus?

What is the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory (THI)?

What is included in the physical exam for tinnitus?

What is the role of lab studies in the diagnosis of tinnitus?

What is the role of surgery in the treatment of tinnitus?

What is the role of hearing aids in the treatment of tinnitus?

What is the role of electrical stimulation in the treatment of tinnitus?

What is the role of biofeedback in the treatment of tinnitus?

What is the role of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) in the treatment of tinnitus?

What is the role of neuromonics in the treatment of tinnitus?

What is the role of counseling in the treatment of tinnitus?

What is the role of support groups in the treatment of tinnitus?

What is the role of medications in the treatment of tinnitus?

What is the role of N -methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) in the treatment of tinnitus?

What are tinnitus maskers and how are they used in the treatment of tinnitus?

What is tinnitus feedback retraining?

What is the role of alternative therapies in the treatment of tinnitus?

What is the role of ginkgo biloba in the treatment of tinnitus?

What is the role of niacin in the treatment of tinnitus?

What is the role of supplements in the treatment of tinnitus?

What is the role of acupuncture in the treatment of tinnitus?

What underlying problems may be signified by tinnitus?

What is the pathophysiology of tinnitus?

How is tinnitus measured and quantified?

-

Tinnitus model. Two phenomena in the auditory cortex are associated with peripheral deafferentation: 1) hyperactivity in the lesion projection zone and 2) increased cortical representation of the lesion-edge frequencies (here, C6) in the lesion projection zone. These two phenomena are presumed to be the neurophysiological correlates of tinnitus. The red letters correspond to octave intervals of a fundamental frequency.

-

Masking. In this graphic, masking sounds are applied at C6, the tinnitus frequency. The result is that the sensation of tinnitus is reduced. In the auditory cortex, this corresponds to decreased spontaneous firing rates.