Practice Essentials

A cholesteatoma is defined as a collection of keratinized squamous epithelium trapped within the middle ear space that can erode and destroy vital locoregional structures within the temporal bone. (See the image below.)

Classically, three types of cholesteatomas are identified:

-

Congenital cholesteatomas

-

Primary acquired cholesteatomas

-

Secondary acquired cholesteatomas

Signs and Symptoms

The hallmark symptom of cholesteatoma is painless otorrhea, either unremitting or recurrent in nature. The lesion also usually causes ossicular damage, resulting in conductive hearing loss. In addition, it may result in aural fullness and, rarely, dizziness (if it invades inner ear structures).

Occasionally, cholesteatoma can also present with rare central nervous system (CNS) complications, which include:

-

Sigmoid sinus thrombosis

-

Epidural abscess

-

Meningitis

Contrary to other cholesteatomas, the congenital subtype can be identified behind an intact, normal-appearing tympanic membrane. Prior history in the child of recurrent suppurative ear disease, previous otologic surgery, or tympanic membrane perforation is uncommon. [1, 2, 3, 4] (See the image below.)

A large cholesteatoma. No landmarks are visible, which typically is the case with advanced cholesteatomas.

A large cholesteatoma. No landmarks are visible, which typically is the case with advanced cholesteatomas.

Please see Clinical Presentation for additional details.

Diagnosis

No laboratory tests or biopsies are generally necessary for the diagnosis of cholesteatoma, as the diagnosis relies heavily on clinical history, physical examination, and radiographic findings.

Computed tomography (CT) scanning is the diagnostic imaging modality of choice for these lesions, as it can detect subtle bony defects. Imaging findings may include the following:

-

Nondependent soft tissue density, typically with involvement of the epitympanum and Prussak space

-

Scutum blunting

-

Ossicular erosion (malleus and incus)

-

Mastoid aditus widening

-

Bony ear canal erosion (external auditory canal [EAC] cholesteatoma)

Cholesteatoma can also erode into the facial canal, tegmen tympani, lateral semicircular canal, sigmoid plate, and posterosuperior EAC; this can also be detected on CT imaging.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is used when the following anomalies are suspected [5] :

-

Dural involvement or invasion

-

Subdural or epidural abscess

-

Brain herniation into mastoid cavity

-

Inflammation of membranous labyrinth or facial nerve

-

Sigmoid sinus thrombosis

-

Meningitis

Audiometry should be performed prior to surgery whenever possible. Air and bone conduction, speech reception threshold, and speech discrimination tests should all be conducted before the proposed operative procedure, to establish a hearing baseline.

Histologically, surgically removed cholesteatoma specimens demonstrate typical squamous epithelium. The histology is indistinguishable from that of sebaceous cysts or keratomas removed from any other part of the body.

Please see Workup for additional details.

Management

Generally, all cholesteatomas should be excised. The only absolute contraindications are patient comorbidities that prevent surgical intervention. The types of surgeries include the following.

Canal wall–down tympanomastoidectomy

In the canal wall–down (open) procedure, the posterior canal wall is removed. A large meatoplasty is created to allow adequate air circulation into the mastoid cavity that arises from the operation. Canal wall–down operations have the highest probability of success with regard to treating cholesteatoma.

Canal wall–up tympanomastoidectomy

In the canal wall–up (closed) procedure, the canal wall is preserved, and the normal appearance is maintained. However, there is a risk of persistent and/or recurrent cholesteatomas.

Intact bridge canal wall–down tympanomastoidectomy

The intact bridge canal wall–down tympanomastoidectomy is a contemporary version of a modified radical tympanomastoidectomy with preservation of the bridge, which is the most medial portion of the posterosuperior meatal wall.

Please see Treatment for additional details.

Background

A cholesteatoma consists of squamous epithelium that is trapped within the middle ear space; it can erode and destroy vital structures within the temporal bone.

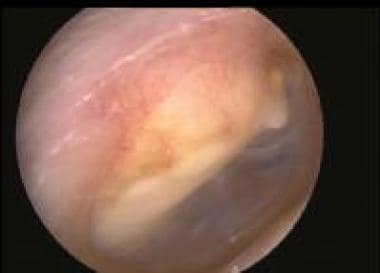

Epitympanic (attic) cholesteatoma. This is a typical primary acquired cholesteatoma in its earliest stages.

Epitympanic (attic) cholesteatoma. This is a typical primary acquired cholesteatoma in its earliest stages.

Throughout the early half of the 20th century, cholesteatomas were classically managed by exteriorization. The mastoid air cells were exenterated, the posterior wall of the external auditory canal was removed, and the opening into the resultant cavity was enlarged to ensure adequate air exchange, allow visual inspection, and make surveillance possible.

During the 1950s and 1960s, the House Otologic Group developed a new approach in which the basic underlying anatomic structure of the ear and temporal bone was left intact, principally by preserving the ear canal wall. This created great controversy, resulting in surgeons aligning themselves with either the old "canal wall–down" (ie, open cavity) procedure [6] or with the new "canal wall–up" (ie, closed cavity) method. [7]

In the United States, the majority of otologic and neurotologic surgeons have now migrated to an intermediate position, using both techniques and selecting the open or closed cavity procedure on a case by case basis.

Etiology and Pathophysiology

Cholesteatomas cause bony erosion by either of the following mechanisms [8] :

- Consistent pressure applied over time, resulting in bony remodeling

- Osteoclastic activity enhanced by enzymatic processes occurring at the margin of an infected cholesteatoma

Using a scanning electron microscope, a study by Wiatr et al found that cholesteatomas with an irregular matrix structure tend to cause more destruction to the middle ear bone walls than do those with a regular, layered structure. [9]

A study by Rosito et al suggested that in patients with posterior epitympanic cholesteatoma confined to the pars flaccida or a two-route cholesteatoma involving both the pars flaccida and pars tensa, the chance of having a labyrinthine fistula in the lateral semicircular canal is increased. In study patients with these cholesteatoma growth patterns, the prevalence of labyrinthine fistula in the lateral semicircular canal was 5.0%, while in patients with other growth patterns, the prevalence altogether was 0.6%. [10]

Occasionally, extratemporal complications can arise in the neck, CNS, or both. Brain dysfunction can occur when a cholesteatoma within the cranium grows large enough to produce mass effect.

Generally, three types of cholesteatoma are identified: congenital, primary acquired, and secondary acquired.

Congenital cholesteatoma

Congenital cholesteatomas arise as a consequence of squamous epithelium trapped within the temporal bone during embryogenesis. They are keratin-filled cysts that are found in the anterior-superior quadrant and are identified most commonly in early childhood. [11]

Congenital cholesteatomas result in conductive hearing loss by obstructing the eustachian tube and consequently accumulating middle ear fluid. They can also expand posteriorly to encase the ossicular chain, another cause of conductive hearing loss.

Contrary to other cholesteatomas, the congenital subtype can be identified behind an intact, normal-appearing tympanic membrane. Prior history in the child of recurrent suppurative ear disease, previous otologic surgery, or tympanic membrane perforation is uncommon. [1, 2, 3, 4]

Bilateral congenital cholesteatoma is extremely rare, with a study by Lee et al finding that out of 604 children with congenital cholesteatoma, 1.8% had the bilateral form. [12]

Primary acquired cholesteatoma

A primary acquired cholesteatoma results from tympanic membrane retraction. A classic case develops from progressive deep medial retraction of the pars flaccida into the epitympanum (attic), slowly eroding the lateral wall of the epitympanum (scutum). This results in a slow expansion of the epitympanum lateral wall. [13]

The tympanic membrane continues to retract medially until it passes over the heads of the ossicles and into the posterior epitympanum, often causing ossicular destruction. Deafness and vertigo may result due to the erosion of the tegmen mastoideum as the cholesteatoma encroaches posteriorly into the aditus ad antrum and the mastoid, exposing the dura and/or eroding the lateral semicircular canal. [14]

Retraction of the posterior quadrant of the tympanic membrane into the posterior middle ear results in the second type of primary acquired cholesteatoma. The drum initially adheres to the long process of the incus; as a result of continued retraction medially and posteriorly, the superstructure of the stapes is enveloped by squamous epithelium, which retracts into the sinus tympani.

Upon surgical removal, it is commonly discovered that cholesteatomas arising from the tympanic membrane have caused facial nerve dehiscence, as well as destruction of the stapedial superstructure, resulting in a challenging removal from the sinus tympani.

Secondary acquired cholesteatoma

Secondary acquired cholesteatomas result directly from injury to the tympanic membrane, frequently in the form of perforations caused by acute otitis media, trauma, or surgical manipulation. Posterior marginal perforations, as opposed to central perforations, are a common source of these cholesteatomas. Deep retraction pockets trap desquamated epithelium, which leads to cholesteatoma formation as well.

Epidemiology

Cholesteatomas are a relatively common reason for otologic surgery (biweekly in tertiary otologic practices). Death from intracranial complications of cholesteatoma is now uncommon, with this change being attributable to earlier recognition, timely surgical intervention, and supportive antibiotic therapy. Cholesteatomas remain a relatively frequent cause of permanent, moderate conductive hearing loss in children and adults.

The exact worldwide incidence of cholesteatomas is unknown, although the incidence has reportedly declined in recent decades; this can be attributed to earlier recognition, timely surgical intervention, and the widespread use of ventilation tubes. The majority of cholesteatoma cases are acquired, with boys making up the preponderance of these.

Prognosis

Surgical excision is generally successful. Cholesteatomas continue to grow if not removed, and multiple surgical procedures may be necessary in cases of recurrence or failure to completely excise the cholesteatoma during the initial surgery. Complications may arise in rare events, including the following:

-

Brain abscess

-

Unilateral hearing loss

-

Vertigo

-

Facial nerve dehiscence leading to paralysis

-

Meningitis

-

Persistent otorrhea

Canal wall–down (open cavity) tympanomastoidectomy offers a very low rate of recurrence or persistence of cholesteatomas. Repeat procedures occur in less than 5% of patients. This compares quite favorably with the 20-40% recurrence rates associated with closed-cavity techniques (canal wall–up). [6]

Nonetheless, as the ossicular chain and/or tympanic membrane cannot always be completely restored to normal, cholesteatoma remains a relatively common cause of permanent, moderate conductive hearing loss.

A literature review by van der Toom et al reported that canal wall–up and canal wall–down tympanoplasty with mastoid obliteration had recurrent and residual cholesteatoma rates that were similar to or better than those for nonobliterative surgery. In canal wall–up tympanoplasty with mastoid obliteration, the recurrent and residual cholesteatoma rates were 0.28% and 4.2%, respectively, while for the canal wall–down procedure with mastoid obliteration, the rates were 5.9% and 5.8%, respectively. [15]

A study by Rosito et al linked cholesteatoma with sensorineural hearing loss. In an analysis of 115 patients with middle ear cholesteatoma on one side, greater bone-conduction thresholds were found in the affected ear than in the contralateral ear at various frequencies. It was also found that the larger the air-bone gap in the affected ear, the greater the damage to the inner ear. [16]

Mortality

Death from intracranial complications of cholesteatoma is uncommon due to early recognition, timely surgical intervention, and supportive antibiotic therapy.

-

Epitympanic (attic) cholesteatoma. This is a typical primary acquired cholesteatoma in its earliest stages.

-

A large epitympanic (attic) cholesteatoma that is much more advanced than the lesion in the previous image.

-

A large cholesteatoma. No landmarks are visible, which typically is the case with advanced cholesteatomas.

-

A cholesteatoma with a white mass can be seen behind an intact drum.

-

An unenhanced computed tomography (CT) scan demonstrating that the posterior canal wall has been eroded and the external auditory canal has filled with cholesteatoma, pus, and debris. Surprisingly, the middle ear appears relatively free of disease, a characteristic of primary acquired cholesteatomas.

-

The photo exhibits a large meatoplasty performed as part of an open cavity (canal wall–down) mastoidectomy. A similar meatoplasty usually is necessary if a clean, dry, problem-free cavity is to be maintained.

-

A typical audiogram demonstrating bilateral conductive hearing loss, which may be observed in an individual with a cholesteatoma.

-

Advanced cholesteatoma with exposure of posterior cranial fossa dura.