Practice Essentials

The parotid duct, or Stensen duct, is the major duct of the parotid gland, which is the major salivary gland. This duct serves as a conduit for saliva between the substance of the parotid gland and the oral cavity. Injury to the parotid duct may be difficult to diagnose; therefore, the initial examining physician must have a high index of suspicion for injuries occurring in the parotid region. Consultation with a specialist should occur if any question as to the integrity of the parotid duct exists. Successful treatment depends on early recognition and appropriate early intervention. Sequelae of inadequate diagnosis and treatment include parotid fistula and sialocele formation, which are inconvenient for the patient and more difficult to treat than the initial injury. [1]

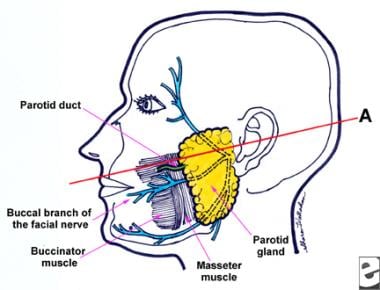

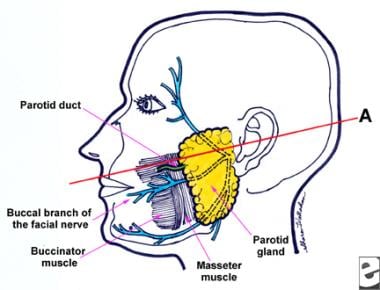

An image depicting the anatomy of the parotid region can be seen below.

Anatomy of the parotid region. Line A connecting the tragus to the midportion of the upper lip estimates the general location of the parotid duct, which lies along the middle third of this line.

Anatomy of the parotid region. Line A connecting the tragus to the midportion of the upper lip estimates the general location of the parotid duct, which lies along the middle third of this line.

Signs and symptoms of parotid duct injuries

Important signs and symptoms related to the wound include pain, fever, edema, discharge, and/or odor.

Workup in parotid duct injuries

Sialography may be performed but is usually not necessary to establish the diagnosis of parotid duct injury. If performed, a water-soluble contrast material should be used because it is more easily drained and absorbed and does not remain as an irritant to the gland.

The most straightforward way to diagnose a parotid duct injury in the emergency department is to cannulate the intraoral parotid duct papilla with a small (ie, 19-gauge) silastic tube and observe if the tube is visible in the wound.

Management of parotid duct injuries

Wounds in the parotid region generally heal well with a low rate of infection, but patients with wounds that involve the oral cavity or require manipulation of the parotid duct through the oral cavity should probably receive prophylactic antibiotics for a brief time after primary closure.

Meticulous wound care is the cornerstone of treatment for penetrating injuries in the parotid region. Copious irrigation has been shown to decrease the incidence of wound infection. Use isotonic sodium chloride solution, dilute Betadine, or dilute hydrogen peroxide to cleanse the wound thoroughly.

Three operative techniques have been popularized over time. These include repair of the duct over a stent, ligation of the duct, and fistulization of the duct into the oral cavity. Radiation has been used in the past to suppress the gland, but use of radiation for benign disease is now avoided. Some authors advocate the use of anticholinergics to suppress glandular function during healing, but this is not a frequently used modality.

History of the Procedure

Parotid duct injuries have been described in the literature for several hundred years, and published surgical treatments of parotid duct injuries began to appear in the 1890s.

Nicoladoni reported the first primary anastomosis of the parotid duct in 1896. [2] Morestin reported ligation of the proximal stump in 1917, and formation of an oral fistula was described in 1918. [3]

Experience in the care of parotid duct injuries greatly increased with the outbreak of World War I, which witnessed many penetrating facial injuries. Many present treatment modalities were developed during the war years.

Epidemiology

Frequency

Approximately 0.21% of patients with penetrating trauma in the parotid region experience an injury to the parotid duct.

Males are twice as likely to experience parotid duct injury as females, a fact probably related to the more aggressive behavior of males.

The mean age of patients with parotid duct injury is approximately 30 years.

Etiology

See the list below:

-

Penetrating injuries in the parotid region

-

Blunt trauma

-

Complication of parotid duct cannulation for sialography

-

Intraoperative iatrogenic injury

Presentation

History

A careful detailed history is necessary to facilitate communication between various health care professionals involved in the care of the patient and to document why the plan of care was appropriate. Patients with damage to the parotid duct often have multiple injuries requiring cooperation of several medical specialists.

Important aspects of the natural history of the wound include the circumstances surrounding the injury, precipitating event or activity, exact mechanism of injury, time of occurrence, location of occurrence, and treatment initiated prior to presentation.

Important signs and symptoms related to the wound include pain, fever, edema, discharge, and/or odor.

Other important aspects of the history include tobacco, alcohol, or recreational drug use; medications or allergies to medications; tetanus immune status; ability to comprehend the magnitude of injury; and ability to cooperate with the treatment plan.

Comorbid conditions that may place the patient at a higher risk for infection or its sequelae include diabetes mellitus, prior splenectomy, liver disease, immunosuppression, and presence of a prosthetic valve or joint.

Physical examination

A thorough physical examination is necessary in order to evaluate the overall state of health, comorbidities, nutritional status, and mental status of the patient. Following the general physical examination, turn attention to the wound. Assessment of the wound can be quite difficult and is often inaccurately or inadequately performed. Adequate examination of the wound may require administration of intravenous or oral pain medication to ensure patient comfort. Children, intoxicated individuals, and individuals with mental disabilities may require general anesthesia to allow adequate wound examination.

Important aspects of wound assessment are listed below.

-

Location

-

Shape

-

Size

-

Type (eg, puncture, laceration, avulsion, crush, abrasion)

-

Depth of penetration

-

Drainage (ie, quality, character, odor)

-

Presence of a foreign body (eg, glass, tooth fragments)

-

Loss of tissue

-

Tenderness

-

Asymmetry

-

Surrounding erythema, edema, cellulitis, or crepitation

-

Facial nerve status

Photographs are a wise addition to the documentation present on the chart.

Indications

See Treatment.

Relevant Anatomy

The parotid glands are the largest salivary glands. The paired parotid glands are formed as epithelial invaginations into the embryologic mesoderm and first appear at approximately 6 weeks' gestation. The glands are roughly pyramidal in shape, with the main body overlying the masseter muscle. The glands extend to the zygomatic process and mastoid tip of the temporal bone and curve around the angle of the mandible to extend to the retromandibular and parapharyngeal spaces.

The gland is divided into superficial and deep lobes with regard to its relation to the facial nerve (ie, cranial nerve VII), which travels through the gland. This division is not truly anatomic but rather is used to facilitate surgical treatment of parotid masses. The facial nerve exits the cranium via the stylomastoid foramen and courses through the substance of the parotid gland. The superficial lobe of the parotid gland rests superficial to or lateral to the facial nerve, and the deep lobe rests deep to or medial to the facial nerve. The facial nerve branches within the substance of the parotid gland in a highly variable pattern.

The parotid duct is approximately 7 cm long and is composed of an inner epithelium, a smooth muscle coat, and an outer adventitial layer much like a blood vessel. The parotid duct exits the parotid gland anteriorly and crosses the superficial border of the masseter. It then turns medially and pierces the buccinator muscle. After traveling for a variable distance between the buccinator muscle and the oral mucosa, it enters the oral cavity through a papilla in the buccal mucosa opposite the second maxillary molar. The course of the parotid duct generally follows a line drawn from the tragus to the midportion of the upper lip. Any injury that crosses this line should be considered to involve the parotid duct until proven otherwise. Parotid duct injuries are often overlooked because of more severe concomitant injury or difficulty in obtaining the diagnosis.

The parotid duct travels adjacent to the buccal branch of the facial nerve and the transverse facial artery, which also are at risk in injuries causing damage to the parotid duct. In a cadaveric study, eighty-five percent of the cadavers had a single buccal branch of the facial nerve, whereas 15% had two branches. In 75% of cases, the nerve was inferior to the duct as it emerged from the parotid gland, whereas in 25% of cases the nerve crossed the duct, usually from superior to inferior. The parotid duct was found to be interrelated with the buccal fat pad in cadaveric dissections.

In addition, a 26% chance of injuring the parotid duct exists with the removal of the buccal fat pad. The transverse facial artery, if injured, need not be repaired. However, injury to this artery may cause bleeding into the tissues, which may obscure adequate delineation of structures and confuse the diagnosis. Above all, blind clamping of bleeding vessels in the wound is strongly discouraged because of the extremely high risk of further damage to the delicate structures in this area.

Anatomy of the parotid region. Line A connecting the tragus to the midportion of the upper lip estimates the general location of the parotid duct, which lies along the middle third of this line.

Anatomy of the parotid region. Line A connecting the tragus to the midportion of the upper lip estimates the general location of the parotid duct, which lies along the middle third of this line.

An injury classification system has been devised for parotid duct injuries. This system divides the parotid duct into the following 3 regions:

-

Posterior to the masseter or intraglandular (site A)

-

Overlying the masseter (site B)

-

Anterior to the masseter (site C)

Contraindications

Wounds older than 24 hours should probably be managed expectantly because many heal without untoward event.

-

Anatomy of the parotid region. Line A connecting the tragus to the midportion of the upper lip estimates the general location of the parotid duct, which lies along the middle third of this line.

-

Laceration of the parotid duct over the masseter. Note that a stent has been placed through the intraoral papilla and can be visualized in the wound exiting the distal end of the transected duct.

-

Repair of the parotid duct over a silastic stent with interrupted sutures using loupe or microscopic magnification.