Background

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is estimated to affect 32 million persons in the United States and is the fourth leading cause of death in this country. Patients typically have symptoms of both chronic bronchitis and emphysema, but the classic triad also includes asthma. Most of the time COPD is secondary to tobacco abuse, although cystic fibrosis, alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency, bronchiectasis, and some rare forms of bullous lung diseases may be causes as well.

Patients with COPD are susceptible to many insults that can lead rapidly to an acute deterioration superimposed on chronic disease. COPD exacerbation is an important but occasionally overlooked parameter. COPD exacerbations are very common, affecting about 20% of patients with moderate-to-severe COPD (1.3 events per year in patients with 40-45% predicted FEV1). A large observational cohort study found that the rate of COPD exacerbations reflects an independent susceptibility phenotype. [1] Knowledge of this susceptibility phenotype may have implications for targeting treatment of exacerbation and prevention across all COPD severities. Quick and accurate recognition of these patients along with aggressive and prompt intervention may be the only action that prevents frank respiratory failure.

For more information, see Medscape's COPD Resource Center.

Pathophysiology

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a mixture of three separate disease processes that together form the complete clinical and pathophysiological picture. These processes are chronic bronchitis, emphysema and, to a lesser extent, asthma. Progression of COPD is characterized by the accumulation of inflammatory mucous exudates in the lumens of small airways and the thickening of their walls. These walls become infiltrated by adaptive and innate inflammatory immune cells. Infiltration of the airways with substances such as polynuclear and mononuclear phagocytes and CD4 T cells increases with each stage of disease progression. This is also true for B cells and CD8 T cells, which organize into lymphoid follicles. This chronic inflammatory process is associated with tissue repair and remodeling that ultimately determines the pathologic type of COPD.

It appears that smoking may overcome the body's natural mechanisms for limiting this immune response. This process can continue in susceptible individuals even after smoking cessation. Even if the original noxious insults are removed, COPD is still characterized by progressive accumulation of cells of the immune system, fibrosis, and mucus hypersecretion. The molecular basis for the lung inflammation seen in COPD is still an area of great research and debate, with the potential roles of cytokines, complex autoimmune processes, and immune modulation from chronic infection all under investigation.

The defining feature of COPD is irreversible airflow limitation during forced expiration. This may be a result of a loss of elastic recoil due to lung tissue destruction or an increase in the resistance of the conducting airways. The standard measure of COPD is the measure of forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) and its ratio to forced vital capacity (FVC), FEV1/FVC.

Each case of COPD is unique in the blend of processes; however, 2 main types of the disease are recognized.

Chronic bronchitis

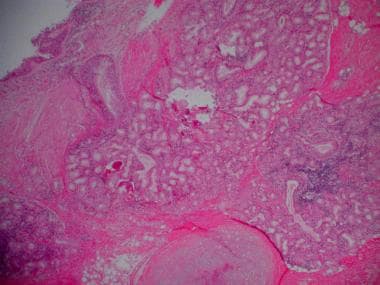

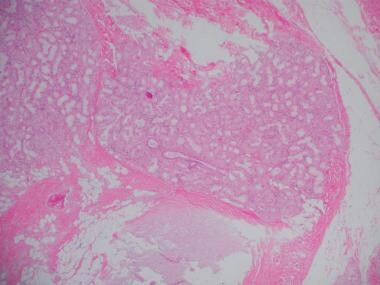

In this type, chronic bronchitis plays the major role. Chronic bronchitis is defined by excessive mucus production with airway obstruction and notable hyperplasia of mucus-producing glands, as depicted in the images below.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Histopathology of chronic bronchitis showing hyperplasia of mucous glands and infiltration of the airway wall with inflammatory cells.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Histopathology of chronic bronchitis showing hyperplasia of mucous glands and infiltration of the airway wall with inflammatory cells.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Histopathology of chronic bronchitis showing hyperplasia of mucous glands and infiltration of the airway wall with inflammatory cells (high-powered view).

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Histopathology of chronic bronchitis showing hyperplasia of mucous glands and infiltration of the airway wall with inflammatory cells (high-powered view).

Damage to the endothelium impairs the mucociliary response that clears bacteria and mucus. Inflammation and secretions provide the obstructive component of chronic bronchitis. In contrast to emphysema, chronic bronchitis is associated with a relatively undamaged pulmonary capillary bed. Emphysema is present to a variable degree but usually is centrilobular rather than panlobular. The body responds by decreasing ventilation and increasing cardiac output. This V/Q mismatch results in rapid circulation in a poorly ventilated lung, leading to hypoxemia and polycythemia.

Eventually, hypercapnia and respiratory acidosis develop, leading to pulmonary artery vasoconstriction and cor pulmonale. With the ensuing hypoxemia, polycythemia, and increased CO2 retention, these patients have signs of right heart failure and are known as "blue bloaters."

Emphysema

The second major type is that in which emphysema is the primary underlying process. Emphysema is defined by destruction of airways distal to the terminal bronchiole.

Physiology of emphysema involves gradual destruction of alveolar septae and of the pulmonary capillary bed, leading to decreased ability to oxygenate blood. The body compensates with lowered cardiac output and hyperventilation. This V/Q mismatch results in relatively limited blood flow through a fairly well oxygenated lung with normal blood gases and pressures in the lung, in contrast to the situation in blue bloaters. Because of low cardiac output, however, the rest of the body suffers from tissue hypoxia and pulmonary cachexia. Eventually, these patients develop muscle wasting and weight loss and are identified as "pink puffers."

Etiology of COPD

In general, the vast majority of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) cases are the direct result of tobacco abuse. [2] While other causes are known, such as alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency, cystic fibrosis, air pollution, occupational exposure (eg, firefighters), and bronchiectasis, this is a disease process that is somewhat unique in its direct correlation to a human activity.

Epidemiology

US frequency

In smokers, two thirds of men and one fourth of women have emphysema at death. Overall, 6.3% of the US adult population have been told by a healthcare worker that they have chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), or about 15 million individuals. It is notable that many more have never been formally diagnosed.

Sex

Men are more likely to have COPD than women.

Age

COPD occurs predominantly in individuals older than 40 years.

Prognosis

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is the fourth leading cause of death in the United States, affecting 32 million adults. It is also the sixth leading cause of death worldwide. [3]

Patient's age and postbronchodilator FEV1 are the most important predictors of prognosis. Young age and FEV1 greater than 50% of predicted are associated with a good prognosis. Older patients and those with more severe lung disease do worse.

Supplemental oxygen (when indicated) has been shown to increase survival rates.

Smoking cessation improves the prognosis.

Cor pulmonale, hypercapnia, tachycardia, and malnutrition indicate a poor prognosis.

Patient Education

The best education comes in two forms. Educate patients to the dangers of smoking and the improvement in quality of life attainable with smoking cessation. Instruct patients with COPD to present early during an exacerbation and to not wait until they are in distress.

This author's observation is that many people with respiratory disease do not know the basic ways to monitor their own disease fluctuations. In addition, they are frequently not taking/using their inhalers as prescribed. Spending the 5 minutes it takes to make sure they have an aero chamber, are using the right dosages, the right medicines, and know when to seek help can go a long way in preventing a respiratory disaster.

Printed material is available from the National Jewish Hospital in Denver, Colorado, as well as the American Lung Association.

Instruct patients about appropriate pulmonary toilet.

For patient education resources, visit the Lung Disease and Respiratory Health Center. Also, see the patient education articles Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD), Smoking (Cigarette), Asthma, and Emphysema.

-

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Histopathology of chronic bronchitis showing hyperplasia of mucous glands and infiltration of the airway wall with inflammatory cells.

-

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Histopathology of chronic bronchitis showing hyperplasia of mucous glands and infiltration of the airway wall with inflammatory cells (high-powered view).

-

Posteroanterior (PA) and lateral chest radiograph in a patient with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Hyperinflation, depressed diaphragms, increased retrosternal space, and hypovascularity of lung parenchyma is demonstrated.

-

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). A lung with emphysema shows increased anteroposterior (AP) diameter, increased retrosternal airspace, and flattened diaphragms on lateral chest radiograph.

-

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). A lung with emphysema shows increased anteroposterior (AP) diameter, increased retrosternal airspace, and flattened diaphragms on posteroanterior chest radiograph.

-

Subcutaneous emphysema and pneumothorax.