Practice Essentials

Cholelithiasis involves the presence of gallstones (see the image below), which are concretions that form in the biliary tract, usually in the gallbladder. Choledocholithiasis refers to the presence of one or more gallstones in the common bile duct (CBD). Treatment of gallstones depends on the stage of disease.

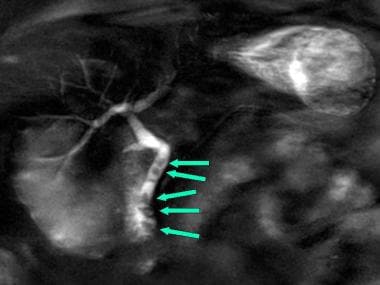

Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) showing 5 gallstones in the common bile duct (arrows). In this image, bile in the duct appears white; stones appear as dark-filling defects. Similar images can be obtained by taking plain radiographs after injection of radiocontrast material in the common bile duct, either endoscopically (endoscopic retrograde cholangiography) or percutaneously under fluoroscopic guidance (percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography), but these approaches are more invasive.

Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) showing 5 gallstones in the common bile duct (arrows). In this image, bile in the duct appears white; stones appear as dark-filling defects. Similar images can be obtained by taking plain radiographs after injection of radiocontrast material in the common bile duct, either endoscopically (endoscopic retrograde cholangiography) or percutaneously under fluoroscopic guidance (percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography), but these approaches are more invasive.

Signs and symptoms

Gallstone disease may be thought of as having the following four stages:

Lithogenic state, in which conditions favor gallstone formation

Asymptomatic gallstones

Symptomatic gallstones, characterized by episodes of biliary colic

Complicated cholelithiasis

Symptoms and complications result from effects occurring within the gallbladder or from stones that escape the gallbladder to lodge in the CBD.

Characteristics of biliary colic include the following:

-

Sporadic and unpredictable episodes

-

Pain that is localized to the epigastrium or right upper quadrant, sometimes radiating to the right scapular tip

-

Pain that begins postprandially, is often described as intense and dull, typically lasts 1-5 hours, increases steadily over 10-20 minutes, and then gradually wanes

-

Pain that is constant; not relieved by emesis, antacids, defecation, flatus, or positional changes; and sometimes accompanied by diaphoresis, nausea, and vomiting

-

Nonspecific symptoms (eg, indigestion, dyspepsia, belching, or bloating)

Patients with the lithogenic state or asymptomatic gallstones have no abnormal findings on physical examination.

Distinguishing uncomplicated biliary colic from acute cholecystitis or other complications is important. Key findings that may be noted include the following:

-

Uncomplicated biliary colic – Pain that is poorly localized and visceral; an essentially benign abdominal examination without rebound or guarding; absence of fever

-

Acute cholecystitis – Well-localized pain in the right upper quadrant, usually with rebound and guarding; positive Murphy sign (nonspecific); frequent presence of fever; absence of peritoneal signs; frequent presence of tachycardia and diaphoresis; in severe cases, absent or hypoactive bowel sounds

The presence of fever, persistent tachycardia, hypotension, or jaundice necessitates a search for complications, which may include the following:

-

Other systemic causes

See Presentation for more detail.

Diagnosis

Patients with uncomplicated cholelithiasis or simple biliary colic typically have normal laboratory test results; laboratory studies are generally not necessary unless complications are suspected. Blood tests, when indicated, may include the following:

-

Complete blood count (CBC) with differential

-

Liver function panel

-

Amylase

-

Lipase

Imaging modalities that may be useful include the following:

-

Abdominal radiography (upright and supine) – Used primarily to exclude other causes of abdominal pain (eg, intestinal obstruction)

-

Ultrasonography – The procedure of choice in suspected gallbladder or biliary disease

-

Endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) – An accurate and relatively noninvasive means of identifying stones in the distal CBD

-

Laparoscopic ultrasonography – Promising as a potential method for bile duct imaging during laparoscopic cholecystectomy

-

Computed tomography (CT) – More expensive and less sensitive than ultrasonography for detecting gallbladder stones, but superior for demonstrating stones in the distal CBD

-

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) – Usually reserved for cases in which choledocholithiasis is suspected

-

Scintigraphy – Highly accurate for the diagnosis of cystic duct obstruction

-

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP)

-

Percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (PTC)

See Workup for more detail.

Management

The treatment of gallstones depends upon the stage of the disease, as follows:

-

Lithogenic state – Interventions are currently limited to a few special circumstances

-

Asymptomatic gallstones – Expectant management

-

Symptomatic gallstones – Usually, definitive surgical intervention (eg, cholecystectomy), although medical dissolution may be considered in some cases

Medical treatments, used individually or in combination, include the following:

-

Oral bile salt therapy (ursodeoxycholic acid)

-

Extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy

Cholecystectomy for asymptomatic gallstones may be indicated in the following patients:

-

Those with large (>2 cm) gallstones

-

Those who have a nonfunctional or calcified (porcelain) gallbladder on imaging studies and are at high risk of gallbladder carcinoma

-

Those with spinal cord injuries or sensory neuropathies affecting the abdomen

-

Those with sickle cell anemia in whom the distinction between painful crisis and cholecystitis may be difficult

Patients with the following risk factors for complications of gallstones may be offered elective cholecystectomy, even if they have asymptomatic gallstones:

-

Cirrhosis

-

Portal hypertension

-

Children

-

Transplant candidates

-

Diabetes with minor symptoms

Surgical interventions to be considered include the following:

-

Cholecystectomy (open or laparoscopic)

-

Cholecystostomy

-

Endoscopic sphincterotomy

See Treatment and Medication for more detail.

Background

Cholelithiasis is the medical term for gallstone disease. Gallstones are concretions that form in the biliary tract, usually in the gallbladder (see the image below).

Excised gall bladder opened to show 3 gallstones. Image from Science Source (http://www.sciencesource.com/).

Excised gall bladder opened to show 3 gallstones. Image from Science Source (http://www.sciencesource.com/).

Gallstones develop insidiously, and they may remain asymptomatic for decades. Migration of a gallstone into the opening of the cystic duct may block the outflow of bile during gallbladder contraction. The resulting increase in gallbladder wall tension produces a characteristic type of pain (biliary colic). Cystic duct obstruction, if it persists for more than a few hours, may lead to acute gallbladder inflammation (acute cholecystitis).

Choledocholithiasis refers to the presence of one or more gallstones in the common bile duct. Usually, this occurs when a gallstone passes from the gallbladder into the common bile duct (see the image below).

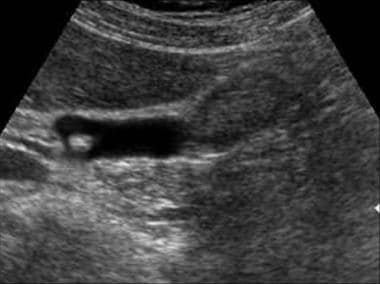

Common bile duct stone (choledocholithiasis). The sensitivity of transabdominal ultrasonography for choledocholithiasis is approximately 75% in the presence of dilated ducts and 50% for nondilated ducts. Image courtesy of DT Schwartz.

Common bile duct stone (choledocholithiasis). The sensitivity of transabdominal ultrasonography for choledocholithiasis is approximately 75% in the presence of dilated ducts and 50% for nondilated ducts. Image courtesy of DT Schwartz.

A gallstone in the common bile duct may impact distally in the ampulla of Vater, the point where the common bile duct and pancreatic duct join before opening into the duodenum. Obstruction of bile flow by a stone at this critical point may lead to abdominal pain and jaundice. Stagnant bile above an obstructing bile duct stone often becomes infected, and bacteria can spread rapidly back up the ductal system into the liver to produce a life-threatening infection called ascending cholangitis. Obstruction of the pancreatic duct by a gallstone in the ampulla of Vater can trigger activation of pancreatic digestive enzymes within the pancreas itself, leading to acute pancreatitis. [1, 2]

Chronically, gallstones in the gallbladder may cause progressive fibrosis and loss of function of the gallbladder, a condition known as chronic cholecystitis. Chronic cholecystitis predisposes to gallbladder cancer.

Ultrasonography is the initial diagnostic procedure of choice in most cases of suspected gallbladder or biliary tract disease (see Workup).

The treatment of gallstones depends upon the stage of disease. Asymptomatic gallstones may be managed expectantly. Once gallstones become symptomatic, definitive surgical intervention with excision of the gallbladder (cholecystectomy) is usually indicated. Cholecystectomy is among the most frequently performed abdominal surgical procedures (see Treatment). Complications of gallstone disease may require specialized management to relieve obstruction and infection.

See Pediatric Cholelithiasis for complete information on this topic.

Pathophysiology

Gallstone formation occurs because certain substances in the bile are present in concentrations that approach the limits of their solubility. When bile is concentrated in the gallbladder, it can become supersaturated with these substances, which then precipitate from the solution as microscopic crystals. The crystals are trapped in the gallbladder mucus, producing gallbladder sludge. Over time, the crystals grow, aggregate, and fuse to form macroscopic stones. Occlusion of the ducts by sludge and/or stones produces the complications of gallstone disease.

The two main substances involved in gallstone formation are cholesterol and calcium bilirubinate.

Cholesterol gallstones

More than 80% of gallstones in the United States contain cholesterol as their major component. Liver cells secrete cholesterol into bile along with phospholipid (lecithin) in the form of small spherical membranous bubbles, termed unilamellar vesicles. Liver cells also secrete bile salts, which are powerful detergents required for the digestion and absorption of dietary fats.

Bile salts in bile dissolve the unilamellar vesicles to form soluble aggregates called mixed micelles. This happens mainly in the gallbladder, where bile is concentrated by the reabsorption of electrolytes and water.

Compared with vesicles (which can hold up to 1 molecule of cholesterol for every molecule of lecithin), mixed micelles have a lower carrying capacity for cholesterol (about 1 molecule of cholesterol for every 3 molecules of lecithin). If bile contains a relatively high proportion of cholesterol to begin with, then as bile is concentrated, progressive dissolution of vesicles may lead to a state in which the cholesterol-carrying capacity of the micelles and residual vesicles is exceeded. At this point, bile is supersaturated with cholesterol, and cholesterol monohydrate crystals may form.

Thus, the main factors that determine whether cholesterol gallstones will form are (1) the amount of cholesterol secreted by the liver cells, relative to lecithin and bile salts, and (2) the degree of concentration and the extent of stasis of bile in the gallbladder.

Calcium, bilirubin, and pigment gallstones

Bilirubin, a yellow pigment derived from the breakdown of heme, is actively secreted into bile by liver cells. Most of the bilirubin in bile is in the form of glucuronide conjugates, which are water soluble and stable, but a small proportion consists of unconjugated bilirubin. Unconjugated bilirubin, like fatty acids, phosphate, carbonate, and other anions, tends to form insoluble precipitates with calcium. Calcium enters bile passively along with other electrolytes.

In situations of high heme turnover, such as chronic hemolysis or cirrhosis, unconjugated bilirubin may be present in bile at higher than normal concentrations. Calcium bilirubinate may then crystallize from the solution and eventually form stones. Over time, various oxidations cause the bilirubin precipitates to take on a jet-black color, and stones formed in this manner are termed black pigment gallstones. Black pigment stones represent 10%-20% of gallstones in the United States.

Bile is normally sterile, but in some unusual circumstances (eg, above a biliary stricture), it may become colonized with bacteria. The bacteria hydrolyze conjugated bilirubin, and the resulting increase in unconjugated bilirubin may lead to precipitation of calcium bilirubinate crystals.

Bacteria also hydrolyze lecithin to release fatty acids, which also may bind calcium and precipitate from the solution. The resulting concretions have a claylike consistency and are termed brown pigment stones. Unlike cholesterol or black pigment gallstones, which form almost exclusively in the gallbladder, brown pigment gallstones often form de novo in the bile ducts. Brown pigment gallstones are unusual in the United States but are fairly common in some parts of Southeast Asia, possibly related to liver fluke infestation.

Mixed gallstones

Cholesterol gallstones may become colonized with bacteria and can elicit gallbladder mucosal inflammation. Lytic enzymes from the bacteria and leukocytes hydrolyze bilirubin conjugates and fatty acids. As a result, over time, cholesterol stones may accumulate a substantial proportion of calcium bilirubinate and other calcium salts, producing mixed gallstones. Large stones may develop a surface rim of calcium resembling an eggshell that may be visible on plain x-ray films.

Etiology

Cholesterol gallstones, black pigment gallstones, and brown pigment gallstones have different pathogeneses and different risk factors.

Cholesterol gallstones

Cholesterol gallstones are associated with female sex, European or Native American ancestry, and increasing age. Other risk factors include the following:

-

Obesity

-

Pregnancy

-

Gallbladder stasis

-

Drugs

-

Heredity

The metabolic syndrome of truncal obesity, insulin resistance, type II diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia is associated with increased hepatic cholesterol secretion and is a major risk factor for the development of cholesterol gallstones.

Cholesterol gallstones are more common in women who have experienced multiple pregnancies. A major contributing factor is thought to be the high progesterone levels of pregnancy. Progesterone reduces gallbladder contractility, leading to prolonged retention and greater concentration of bile in the gallbladder.

Other causes of gallbladder stasis associated with increased risk of gallstones include high spinal cord injuries, prolonged fasting with total parenteral nutrition, and rapid weight loss associated with severe caloric and fat restriction (eg, diet, gastric bypass surgery [3] ).

A number of medications are associated with the formation of cholesterol gallstones. Estrogens administered for contraception or for the treatment of prostate cancer increase the risk of cholesterol gallstones by increasing biliary cholesterol secretion. Clofibrate and other fibrate hypolipidemic drugs increase hepatic elimination of cholesterol via biliary secretion and appear to increase the risk of cholesterol gallstones. Somatostatin analogues appear to predispose to gallstones by decreasing gallbladder emptying.

About 25% of the predisposition to cholesterol gallstones appears to be hereditary, as judged from studies of identical and fraternal twins. At least a dozen genes may contribute to the risk. [4] A rare syndrome of low phospholipid–associated cholelithiasis occurs in individuals with a hereditary deficiency of the biliary transport protein required for lecithin secretion. [5, 6]

Black and brown pigment gallstones

Black pigment gallstones occur disproportionately in individuals with high heme turnover. Disorders of hemolysis associated with pigment gallstones include sickle cell anemia, hereditary spherocytosis, and beta-thalassemia. In cirrhosis, portal hypertension leads to splenomegaly. This, in turn, causes red cell sequestration, leading to a modest increase in hemoglobin turnover. About half of all cirrhotic patients have pigment gallstones.

Prerequisites for the formation of brown pigment gallstones include intraductal stasis and chronic colonization of bile with bacteria. In the United States, this combination is most often encountered in patients with postsurgical biliary strictures or choledochal cysts.

In rice-growing regions of East Asia, infestation with biliary flukes may produce biliary strictures and predispose to formation of brown pigment stones throughout intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile ducts. This condition, termed hepatolithiasis, causes recurrent cholangitis and predisposes to biliary cirrhosis and cholangiocarcinoma.

Other comorbidities

Crohn disease, ileal resection, or other diseases of the ileum decrease bile salt reabsorption and increase the risk of gallstone formation.

Other illnesses or states that predispose to gallstone formation include burns, use of total parenteral nutrition, paralysis, ICU care, and major trauma. This is due, in general, to decreased enteral stimulation of the gallbladder with resultant biliary stasis and stone formation.

Epidemiology

The prevalence of cholelithiasis is affected by many factors, including ethnicity, gender, comorbidities, and genetics.

United States statistics

In the United States, about 20 million people (10%-20% of adults) have gallstones. Every year 1%-3% of people develop gallstones and about 1%-3% of people become symptomatic. Each year, in the United States, approximately 500,000 people develop symptoms or complications of gallstones requiring cholecystectomy.

Gallstone disease is responsible for about 10,000 deaths per year in the United States. About 7000 deaths are attributable to acute gallstone complications, such as acute pancreatitis. About 2000-3000 deaths are caused by gallbladder cancers (80% of which occur in the setting of gallstone disease with chronic cholecystitis). Although gallbladder surgery is relatively safe, cholecystectomy is a very common procedure, and its rare complications result in several hundred deaths each year.

International statistics

The prevalence of cholesterol cholelithiasis in other Western cultures is similar to that in the United States, but it appears to be somewhat lower in Asia and Africa.

A Swedish epidemiologic study found that the incidence of gallstones was 1.39 per 100 person-years. [7] In an Italian study, 20% of women had stones, and 14% of men had stones. In a Danish study, gallstone prevalence in persons aged 30 years was 1.8% for men and 4.8% for women; gallstone prevalence in persons aged 60 years was 12.9% for men and 22.4% for women.

The prevalence of choledocholithiasis is higher internationally than in the United States, mainly because of the additional risk of primary common bile duct stones caused by parasitic infestation with liver flukes such as Clonorchis sinensis.

Race-, sex-, and age-related demographics

Prevalence of gallstones is highest in people of northern European descent, and in Hispanic populations and Native American populations. [8] Prevalence of gallstones is lower in Asians and African Americans.

Women are more likely to develop cholesterol gallstones than men, especially during their reproductive years, when the incidence of gallstones in women is 2-3 times that in men. The difference appears to be attributable mainly to estrogen, which increases biliary cholesterol secretion. [9]

Risk of developing gallstones increases with age. Gallstones are uncommon in children in the absence of congenital anomalies or hemolytic disorders. Beginning at puberty, the concentration of cholesterol in bile increases. After age 15 years, the prevalence of gallstones in US women increases by about 1% per year; in men, the rate is less, about 0.5% per year. Gallstones continue to form throughout adult life, and the prevalence is greatest at advanced age. The incidence in women falls with menopause, but new stone formation in men and women continues at a rate of about 0.4% per year until late in life.

Among individuals undergoing cholecystectomy for symptomatic cholelithiasis, 8%-15% of patients younger than 60 years have common bile duct stones, compared with 15%-60% of patients older than 60 years.

Prognosis

Less than half of patients with gallstones become symptomatic. The mortality rate for an elective cholecystectomy is 0.5% with less than 10% morbidity. The mortality rate for an emergent cholecystectomy is 3%-5% with 30%-50% morbidity.

Following cholecystectomy, stones may recur in the bile duct. Separately, single-incisional laparoscopic cholecystectomy appears to be associated with an incisional hernia rate of 8%, with age (≥50 years) and body mass index (BMI) (≥30 kg/m2) as independent predictive factors. [10]

Approximately 10%-15% of patients have an associated choledocholithiasis. The prognosis in patients with choledocholithiasis depends on the presence and severity of complications. Of all patients who refuse surgery or are unfit to undergo surgery, 45% remain asymptomatic from choledocholithiasis, while 55% experience varying degrees of complications.

Patient Education

Patients with asymptomatic gallstones should be educated to recognize and report the symptoms of biliary colic and acute pancreatitis. Alarm symptoms include persistent epigastric pain lasting for greater than 20 minutes, especially if accompanied by nausea, vomiting, or fever. If pain is severe or persists for more than an hour, the patient should seek immediate medical attention.

For patient education information, see the Digestive Disorders Center and Cholesterol Center, as well as Gallstones.

-

Excised gall bladder opened to show 3 gallstones. Image from Science Source (http://www.sciencesource.com/).

-

Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) showing 5 gallstones in the common bile duct (arrows). In this image, bile in the duct appears white; stones appear as dark-filling defects. Similar images can be obtained by taking plain radiographs after injection of radiocontrast material in the common bile duct, either endoscopically (endoscopic retrograde cholangiography) or percutaneously under fluoroscopic guidance (percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography), but these approaches are more invasive.

-

Intraoperative cholangiogram demonstrating a distal common bile duct stone with dilatation.

-

Intraoperative cholangiogram demonstrating a distal common bile duct stone without dilatation.

-

Cholecystitis with small stones in the gallbladder neck. Classic acoustic shadowing is seen beneath the gallstones. The gallbladder wall is greater than 4 mm. Image courtesy of DT Schwartz.

-

The WES (wall echogenic shadow) sign, long axis of the gallbladder. The arrow head points to the gallbladder wall. The second hyperechoic line represents the edge of the congregated gallstones. Acoustic shadowing (AS) is readily seen. The common bile duct can be seen just above the portal vein (PV). Image courtesy of Stephen Menlove.

-

Wall echogenic shadow (WES sign), short axis view of the gallbladder. Image courtesy of Stephen Menlove.

-

Sludge in the gallbladder. Note the lack of shadowing. Image courtesy of DT Schwartz.

-

Common bile duct stone (choledocholithiasis). The sensitivity of transabdominal ultrasonography for choledocholithiasis is approximately 75% in the presence of dilated ducts and 50% for nondilated ducts. Image courtesy of DT Schwartz.

-

What are gallstones? Gallstones are solid stones that are produced in the gallbladder when there’s an imbalance in the composition of bile. The main types of gallstones are cholesterol stones, bilirubin stones, and brown stones.