Overview

Other articles in the CBRNE section (see CBRNE - Biological Warfare Agents and CBRNE - Evaluation of a Biological Warfare Victim) discuss the specific clinical management issues involved with treatment of patients exposed to potential bioterrorism pathogens and toxins. [1, 2] This article focuses on the larger logistic and emergency management issues of such an event. The complex relationships among various medical disciplines and with the rest of the response community cannot be overemphasized. Medical support falls within the realms of public health, emergency medical services, and traditional fixed site health care. Appreciating that a bioterrorist event is a hybrid disaster, with similarities to a public health emergency and a traditional disaster, is important. [3, 4, 5]

Assumptions

The following assumptions must be made concerning a bioterrorist event to effectively and realistically plan for response [6, 7] :

-

With or without advanced warning, the actual time and location of the release of a biological agent most likely will be covert.

-

Terrorists desiring maximum effect will opt for aerosolized release of the pathogen.

-

Exposed individuals will have minimal physical and immunologic protection.

-

Signs and symptoms of illness will be delayed from hours to weeks and initially may mimic minor nonspecific illnesses or naturally produced disease syndromes.

-

Arrival of assistance from state or federal agencies will be delayed from 24-72 hours after request and may take longer for full operation.

Pre-event Procedures

Threat awareness and pre-event surveillance

Successful treatment of patients exposed to many of the biological agents is exquisitely time dependent. Morbidity and mortality increase significantly with any delay. Barring discovery by law enforcement or intelligence communities or terrorist announcement of an impending release, the determination that a bioterrorism event has occurred most likely falls to the medical community. [8] The determination of a bioterrorism event by the medical community is through the following:

-

Presumptive diagnoses by astute clinicians

-

During an autopsy or as the result of specific diagnostic tests ordered based on a patient's clinical condition

-

Result of epidemiologic investigations

Pre-event communication with law enforcement

Communication between the medical and law enforcement communities has been rare in the past. Physicians are reluctant to breach patient confidentiality. Law enforcement personnel do not wish to compromise ongoing investigations, share information that is "law enforcement sensitive (LES)" beyond law enforcement agencies, or unduly alarm the public, especially when evidence or information is not explicit enough to validate suspicions. Nonetheless, information sharing between these disciplines should be explored. Terrorist activities, thefts from biological laboratories, or information received from police agencies may impart forewarning if provided in a timely, discrete manner to appropriate offices of the local healthcare network.

Conversely, if a diagnosis associated with pathogen production is made, passing this information on to the appropriate authorities for further investigation may be prudent. Since entry into the healthcare system is often through emergency departments and primary care clinics, open dialogue between these providers and law enforcement personnel is advisable and encouraged.

Event Discovery

Event discovery by clinical providers

Frontline clinicians may be singularly positioned to be first to identify a possible bioterrorism attack. [9] However, sole reliance on this method of discovery is fraught with problems. Many pathogens produce early symptoms that mimic naturally occurring diseases. Some findings are so ubiquitous and nonspecific that rarely does a provider order further laboratory or radiographic tests early in the course of the disease, unless significant physiologic derangements are present or the index of suspicion is raised because of prior intelligence information. Most physicians have not evaluated or treated patients with many of the diseases produced by these agents. Since a delay occurs between exposure and symptoms, patients present at various times, to various care providers, rather than simultaneously to one location.

Event discovery by diagnostic tests or at autopsy

Most diagnostic studies performed early are nonspecific, and few laboratories are equipped to provide the sophisticated testing required to identify the specific pathogens used in a bioterrorist attack. [10] A patient presenting with findings consistent with early Venezuelan equine encephalitis looks remarkably similar to any other patient with aseptic meningitis, and routine testing of cerebrospinal fluid does not alter this picture. This exact problem occurred during the initial outbreak of West Nile virus encephalitis in New York City in the summer of 1999. [11] Findings and initial tests were consistent with St. Louis encephalitis, and several months passed before the causative agent was determined to be West Nile virus.

Laboratory workers attempting to isolate certain pathogens without the proper equipment or safeguards are at risk. In general, smallpox and the various viral hemorrhagic fever viruses should be isolated only in laboratories with Biosafety level IV capabilities. Currently, there are limited facilities in the United States that have such capabilities. Other organisms, such as Yersinia pestis, require Biosafety level III capabilities for appropriate safety.

Many viral pathogens require sophisticated testing, such as enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) or polymerase chain reaction (PCR), that is not widely available. Finally, definitive diagnosis of those pathogens not requiring sophisticated testing or extreme safety precautions requires time for culture growth. Still, certain pathogens can be identified in local laboratories, at least to the degree to justify empiric treatment and healthcare network alert. Y pestis is a bipolar gram-negative rod that can be identified through Gram stain. The identification of Brucella species in conjunction with a suggestive clinical picture may trigger expedient actions based on a presumptive diagnosis only.

Only anthrax produces nearly pathognomic radiographic findings; suspect anthrax in any previously healthy patient with rapidly progressive sepsis and an unexplained widened mediastinum on routine chest film.

Unless accompanied by acral or digital necrosis due to small vessel thrombosis or by hemoptysis and gram-negative rods in the sputum of large numbers of previously healthy patients, the lobar pneumonia of inhalational plague may be misdiagnosed in the clinical setting.

In fact, pathologists may be the first clinicians to consider bioterrorism. Unfortunately, many pathogens produce nearly identical gross and microscopic findings at necropsy, and further tests are required. However, very few pathogens produce the extensive necrotizing hemorrhagic mediastinitis found in a patient who has succumbed to inhalational anthrax. [12]

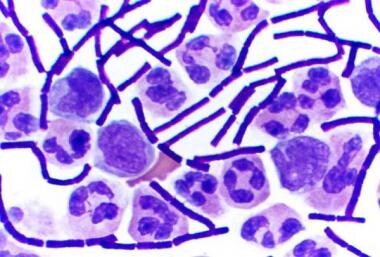

The image below illustrates gram stained cerebrospinal fluid showing gram-positive anthrax baccilli (purple rods).

Gram stained cerebrospinal fluid showing gram-positive anthrax baccilli (purple rods). Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Gram stained cerebrospinal fluid showing gram-positive anthrax baccilli (purple rods). Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Discovery through population-based surveillance

Two distinct subsets of evaluations may assist in accelerating the discovery of a bioterrorist release of a pathogen: syndromic surveillance and analysis of mined data.

In syndromic surveillance, data are collected from likely portals of entry into the healthcare system on patients who present with specific, prospectively identified clinical syndromes. If an unexpected variation in the incidence of these syndromes appears, a more intense but expedient epidemiologic investigation may be warranted. Problems with this method include the requirement for cooperation by caregivers in providing this information in a timely fashion and balancing the sensitivity and specificity of the analytic method. Data collection and reporting can be labor intensive for a relatively low yield, and few incentives exist for a healthcare system already strapped for resources.

Data mining is a method only now being evaluated fully as a possible investigative tool. Since many of these pathogens produce symptoms or discomfort in victims before specific diagnoses are entertained, affected persons may exhibit predictable behavioral patterns that, if identified, can trigger full-scale investigations. Statistical analysis may identify trends earlier than traditional methods by capturing information such as school or work absenteeism; use of specific over-the-counter medications; use of emergency departments, emergency medical services, or primary care clinics for nontraumatic complaints; raw incidence of animal illnesses; poison center data; and nontrauma deaths.

Should either of these methods identify a significant trend, expedient epidemiologic investigations may be warranted. These investigations require establishing a case definition, identifying those patients who meet established criteria, and determining that the incidence of the particular disease is out of the ordinary. Influenza is a disease of the winter months, and finding it during the winter is expected. Plague, although rare, still is found episodically in certain western states. The finding of even one patient with plague in the Northeast United States, particularly the inhalational form, should trigger, at a minimum, enhanced epidemiologic surveillance.

Epidemiologic investigation is resource intensive, and, barring significant augmentation of staff to collect and analyze data, this method alone may not be responsive enough to serve as the primary means of determining that an event has occurred. Epidemiologic investigation does have great value as the disaster unfolds, as is discussed later.

Bioterrorist Event

Indicators of a possible bioterrorist event

High index of suspicion on the part of clinical providers and an epidemiologic surveillance system that is rapidly responsive, sensitive, and specific are important to early recognition of an event. If a communications network exists that allows free exchange of information, a variety of clues may promote such early recognition. These clues include the following [13] :

-

Large numbers of patients with similar symptoms of disease

-

Large numbers of patients with unexplained symptoms, diseases, or deaths

-

Higher than expected morbidity and mortality associated with a common disease and/or failure to respond to traditional therapy

-

A single case of a disease caused by an uncommon agent

-

Multiple unusual or unexplained clinical syndromes in the same patient

-

Disease with an unusual geographic or seasonal distribution

-

Unusual typical patient distribution

-

Unusual disease presentation

-

Similar genetic type among pathogens from temporally or spatially distinct sources

-

Unusual, atypical, genetically engineered, or antiquated strains of pathogens

-

Endemic disease with a sudden unexplained increase in incidence

-

Simultaneous clusters of similar illness in noncontiguous areas

-

Pathogens or toxins transmitted through aerosol, food, or water contamination, suggestive of sabotage

-

Ill persons presenting at nearly the same time from a point source (eg, a tight cluster of patients meeting case definition), with a compressed epidemiologic curve (the rate of change of new cases is significantly higher than predicted based on historical or modelling data)

-

No illness in persons not exposed to common ventilation systems when illness is observed in those in proximity to those systems

-

Death or illness among animals that may be unexplained or attributed to an agent of bioterrorism that precedes or accompanies illness or death in humans

Diagnosis

Exact diagnosis of diseases caused by biological warfare or terrorism is important for a number of reasons, beyond treating an individual patient. These reasons include the ability to predict the spread of the disease, generate prognoses, and attribute responsibility. Without explicit criteria for identifying cases, these efforts are undermined. The concept of case definitions, used by public health departments and the CDC, is very important in this effort. Some syndromes do not have confirmatory laboratory tests, although laboratory evidence may be a component of the case definition. Other diseases have such characteristic presentations that diagnosis may be based on these findings alone. Some are diagnosed on the basis of epidemiologic data. For many, substantial amounts of information must be collected before a final case classification is possible. Finally, for forensic purposes, the identification of as many of the specific characteristics of the pathogen as possible is important.

Gathering the necessary information and diagnostic testing for classic case definition requires time, especially if sophisticated laboratory tests are required. In the case of a rapidly progressive virulent outbreak, a delay in instituting treatment until definitive diagnosis has been made results in increased morbidity and mortality. Therefore, "diagnosis to treat" becomes a viable and necessary option. This option is most valuable once occurrence of an attack has been determined, but it is also valuable for postprophylactic treatment of the population at risk. Standardized diagnosis to treat criteria have not been developed, but clinicians should work with emergency planners and public health officials to prospectively identify those criteria necessary to commence treatment of large segments of the population prior to definitive diagnosis.

Emergency response to a bioterrorist event

The demand placed on the healthcare system (eg, public hospitals, for-profit hospitals, community health centers, emergency medical services) following a bioterrorism attack will be unprecedented. [14, 15] Indeed, most disasters in US history have been marked by relatively little loss of life in comparison to infrastructure destruction; only 6 disasters in US history have resulted in more than 1000 fatalities. Due to public health initiatives, the concept of major epidemics likewise has been modified. The available model that is closest to an overwhelming, rapidly progressive, infectious disease epidemic is the Spanish influenza epidemic of 1918, in which an estimated 650,000 Americans died and approximately 40% of the population was affected. Community healthcare systems must plan ahead to cooperate and expeditiously expand personnel, resources, and facilities to handle the additional demand for services that such an event would cause.

All states and local areas have emergency response plans that are geared toward natural disasters. A bioterrorism event poses a series of unique challenges. [16] Unlike the typical focal disaster, an epidemic due to a bioterrorism attack will be unpredicted, progressive, and widespread. The following will overwhelm local health services very quickly [16] :

-

Shortfalls of ICU beds, ventilators, and other critical care needs

-

Shortages of chemotherapeutic agents

-

Needs for ancillary or nontraditional treatment centers

-

High demand for mortuary and/or funeral services

-

High demand for social and counseling services

-

Shortages of healthcare workers due to absenteeism

Demands on medical care may last weeks to months after the initial onslaught. Essential community servants (eg, medical care personnel, police, firefighters, ambulance drivers, other first responders) may be affected. Elderly and other high-risk populations may be fearful of leaving their homes and seeking proper medical attention for chronic medical conditions and may require home visits for health care.

Once an event has been discovered, medical management of the ensuing disaster will be focused on alerting the appropriate officials, containing the epidemic, providing postexposure prophylaxis to the population at risk, treating ill patients, handling deceased individuals, and addressing the psychological needs of the community. Because of the criminal nature of such an attack, forensic and law enforcement issues also have to be addressed.

Both medical and public health disaster response activities are coordinated through one organizational structure, the Incident Command System (ICS) that is compliant with the National Incident Management System (NIMS). Many different organizations participate in the response to a disaster. The ICS provides a common organizational structure and language that allows different kinds of agencies and/or multiple jurisdictions of similar agencies to work together effectively in response to a disaster. [15, 17]

ICS structure and hierarchy

The organizational structure of ICS is built around the following 5 major management activities. Note: Not all activities are used for every disaster.

-

Incident command

-

Operations

-

Planning

-

Logistics

-

Financial/administrative

Functional requirements, not titles, determine ICS hierarchy.

Important principles

An important part of disaster planning is the identification of the incident commander and other key positions before a disaster occurs.

ICS must be started early, before an incident gets out of control.

Medical and public health responders, often used to working independently, must adhere to the structure of the ICS in order to avoid potentially negative consequences, including the following:

-

Death of personnel due to lack of training

-

Lack of adequate supplies to provide care

-

Staff working beyond their training or certification

-

Lack of integration with the response of other critical sectors

The structure of ICS is the same regardless of the nature of the disaster. The only difference is in the particular experience of key personnel and the extent of the ICS utilized in a particular disaster.

The images below depict emergency response training activities.

FEMA Hospital Emergency Response Training (HERT) for mass casualty incidents. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

FEMA Hospital Emergency Response Training (HERT) for mass casualty incidents. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Alerting and notification

During planning sessions well before an event, develop a risk communication plan that addresses the timing of release of information to the public, the content of information provided, and the methods of release. Many natural disasters (eg, hurricanes, flooding) allow sufficient forewarning that area evacuation may be possible. For others, such as tornadoes, evacuation may not be possible, but additional precautions and shelter-in-place actions may be taken to lessen the impact of the event. Terrorists are unlikely to afford a community that luxury, and equally doubtful is that local governments will order evacuation based on even a credible threat, given the increasing frequency of biological terrorism hoaxes that have plagued communities across the country in recent years.

Containment

In all probability, the realization that a major epidemic is at hand will precede the exact identification of the pathogen involved. Nonetheless, identification is of utmost importance, since the transmissibility of infection must be known to contain the spread of the disease. Diseases that are transmissible through casual contact, by nonhuman vectors, or by respiratory droplets, such as smallpox or pneumonic plague, carry high rates of secondary infections, whereas other diseases pose little risk to those not initially infected.

Barring identification of the time and location of release and the amount and virulence of the pathogen, determination of the area of exposure and population at risk is very difficult and requires the expeditious and concerted efforts of local public health investigators and epidemiologists supported by state and federal agencies. Agent characteristics may be helpful, since certain pathogens are exquisitely fragile outside a host, regardless of meteorologic conditions. Analysis of activities of initial victims during the prodromal or incubation period is necessary to estimate time and location of release. As more epidemiologic information becomes available, these determinations may be refined.

Once estimates of the area of exposure and population at risk are determined, forced or voluntary isolation and quarantine may reduce the spread to secondary contacts. Isolation is the process of separating infectious persons from others. As a practical point, isolation primarily occurs within the confines of hospitals. Quarantine, originally applied to the maritime industries, is the limitation on freedom of movement to prevent the spread of a disease. Animal and vector control also may be important determinants in containing the spread of certain diseases.

Disease transmission through tainted water supplies is highly unlikely, since routine water purification systems effectively kill most pathogens, and those that survive are not in concentrations sufficient to cause disease. However, one or two notable exceptions exist, such as Cryptosporidium parvum. This organism is quite resistant to chlorine, and very small swallowed doses can cause infection. Recently, several widespread outbreaks involving municipal water supplies and public swimming pools have occurred. [18]

Mass prophylaxis

Postexposure prophylaxis serves 2 purposes: to prevent secondary infections in the case of transmissible diseases and to improve community morbidity and mortality. The prognosis in patients with active disease caused by the common pathogens of warfare or terrorism is uniformly poor, with mortality rates approaching 100% if treatment is delayed until patients become symptomatic. Additionally, very little treatment beyond supportive care is available for many of these patients. The importance of postexposure prophylaxis is obvious and cost effective.

Most hospitals and pharmacies have gone to "just in time" pharmaceutical procurement, and stockpiles to handle surge demand are meager at best at most locations. As part of the federal initiative to address deficiencies in the capability to respond to a bioterrorism attack, the Office of Emergency Preparedness of the Department of Health and Human Services established 4 National Medical Response Teams, and the CDC instituted the National Pharmaceutical Stockpile (NPS) program.

Three National Medical Response Teams, in North Carolina, Colorado, and California, are capable of providing medical treatment after a chemical or biological terrorist event. The response teams are fully deployable within 6 hours to incident sites anywhere in the country with a cache of specialized pharmaceuticals to treat as many as 1000 patients. A fourth team is dedicated to the National Capital Area.

The Strategic National Stockpile (SNS) program consists of a 2-tier response. [19] The first tier consists of eight 12-hour "push packages" of pharmaceuticals and supplies that can be delivered to the scene within 12 hours of the federal decision to deploy the assets. These packages allow for the treatment or prophylaxis of disease caused by a variety of threat agents, including anthrax, tularemia, plague, smallpox, and botulism preparedness. [20] The second tier is the Vendor-Managed Inventory, which arrives at the scene 24-36 hours after activation. The Vendor-Managed Inventory packages consist of additional pharmaceuticals and supplies, tailored to a specific agent, and are sent if needed.

Logistics of mass prophylaxis are magnified by the difficulties in determining the population at risk, and initial estimates are likely to be high. Community emergency planners must have an accurate inventory of pharmaceuticals and medical supplies on hand. They also must have detailed plans and procedures for safeguarding, distributing, and dispensing community stores; for patient screening and tracking; and for receiving, distributing, dispensing, and providing security for arriving SNS supplies. Ambulatory, home-ridden, and homeless patients require provisions. Establish sufficient dispensing locations to prevent an additional burden on hospitals and to ensure delivery of these medications in a timely fashion. The difficult ethical issue of prioritizing who receives critical medications, especially if shortages are anticipated, should be resolved prior to an event.

For more information, see Medscape's Bioterrorism and Disaster Medicine Resource Center.

Mass Patient Care

Another Herculean task is addressing the needs of patients requiring treatment or requesting evaluation for possible treatment. Anticipate a large number of individuals requesting evaluation and treatment who have little or no risk of exposure and who are completely asymptomatic. These latter patients, referred to frequently as the "worried well," result in a significant additional burden, possibly 5-10 times as great as the number of actual ill or injured.

Primary components of mass patient care include the following: (1) personnel and material resource protection, (2) decontamination, (3) triage, (4) treatment, and (5) disposition.

Facility and/or medical personnel protection

Although frequently omitted as first responders in most documents concerning weapons of mass destruction, the true first responders in a covert bioterrorism attack are the healthcare providers and ancillary staff at hospitals, clinics, and private physician offices. [14] Consider both collective and personal protection.

Collective protection includes positive pressure ventilation systems and high-efficiency particulate air filtration. Both require major modifications in existing facilities and are cost prohibitive. Unless the healthcare facility is directly downwind from the release site, virtually no risk of major contamination of the facility by airborne spread is present. However, these systems may be considered for new construction. Expedient collective protection may include shutting off ventilation systems and closing and sealing all exterior doors and windows. Since a bioterrorism attack is most likely to occur at some time prior to discovery, these actions may have little effect on facility personnel protection.

Personal protection includes vaccinations and postexposure chemoprophylaxis, personal protective equipment, and augmented standard infectious disease protocols. Provide chemoprophylaxis to all healthcare personnel as soon as a diagnosis is known. Although many ultimately do not need this treatment, staff shortages at a time of greatly increased demand translate into a further degradation of healthcare response and increased community morbidity.

Controversy continues to exist about the level of personal protective equipment required for hospital personnel. With the exception of the T-2 mycotoxins, intact skin provides an adequate barrier to infection. Re-aerosolization has not been well studied and was considered to be negligible in the past. However, as was demonstrated in the anthrax attacks that occurred in 2001, reaerosolization may occur in certain situations. Unless a patient presents immediately after a release, little risk exists to healthcare providers from exposure to residual weaponized pathogens. However, some agents are highly contagious through respiratory droplets; add these respiratory precautions to standard precautions until the exact diagnosis is made. Personnel involved with decontamination of a suspected bioagent should wear respiratory and splash protection, at a minimum (ie, Occupational Safety and Health Administration Level C).

Decontamination

Most patients who have been infected with a pathogen by a bioterrorism attack do not develop symptoms until 1 day to several weeks after the attack. The exceptions to this are patients exposed to biological toxins, who may develop symptoms several hours after exposure. At present, most biological agents do not survive for long periods outside a host. Even the relatively hardy spore of anthrax is degraded by direct exposure to UV light; consequently, decontamination is not necessary unless the attack is overt and recent. [21] Several cidal and static decontamination solutions are under investigation, but for mass decontaminations, copious amounts of soap and water are probably sufficient. The issue of capture of effluent from decontamination is more significant with chemical than with biological agents, since these pathogens and toxins are denatured through water treatment facilities.

Triage

Traditional triage from a mass casualty event involving trauma primarily is based on physiologic parameters, anatomic sites of injury, and attempts to separate patients requiring minimal effort to stabilize from those who require immediate surgery or further life-saving interventions. Patients with physical injuries or vital signs incompatible with life without extensive use of resources are identified as expectant. Triage in the wake of a bioterrorism attack may require triage based on prognosis alone. In the case of anthrax or pneumonic plague, a patient with any significant symptoms has a very poor prognosis, despite vigorous treatment, and, in the presence of an overwhelming number of patients, these minimally ill patients may need to be triaged to the expectant category based on their poor prognosis. As with postexposure prophylaxis, give some consideration to these potentially difficult decisions prior to the crisis.

Treatment

Local healthcare systems have little time to prepare for a bioterrorism event after the fact. These organizations also may suffer significant staff shortages due to absenteeism or illness among medical personnel. All healthcare systems must modify operations significantly to reduce routine demand while increasing the supply of health care. Healthcare systems must have prospectively developed plans for a graduated expansion of available healthcare. Methods may include the following:

-

Diversion of patients with minor complaints or health problems to other sites of care

-

Public service announcements: Announcements requesting telephone triage may prove beneficial and may protect individuals not affected by the bioterrorist pathogen.

-

Cancellation of elective appointments, procedures, and surgery: In addition to freeing up space, hospital gurneys, and beds, this method makes available staff who may be used to augment other departments and services.

-

Early discharge of unexposed but hospitalized patients to skilled nursing facilities, home health care, or remote healthcare facilities: Patient's families may be able to provide initial posthospitalization care under the direction of visiting nurses or through telephonic direction from hospital care providers.

-

Doubling up of single or even shared hospital rooms

-

Using open wards in auditoriums, cafeterias, or other locations within the confines of the healthcare facilities or establishing expansion facilities near existing hospitals: Although certain aspects of patient privacy and comfort are sacrificed, this method of expansion of facilities was used effectively during the influenza epidemic of 1918. Its purpose primarily is to extend nursing services to more patients than can be accomplished on wards with private rooms.

-

Temporary doubling of shifts for staff

-

Recruitment of volunteers, retired healthcare workers, or students from medical, nursing, dental, lab tech, and other allied healthcare schools from the community: Whether or not volunteers will come in the case of a bioattack cannot be predicted, but volunteers from these sources may serve to expand the pool of available healthcare providers for the expected surge of patients. Expeditious credentialing mechanisms will need to be developed. Many functions in hospitals do not require allied healthcare providers, and volunteers may be of great value in freeing up more skilled personnel.

-

Evacuation of affected patients (may prove problematic): The National Disaster Medical System claims to have nearly 100,000 beds available nationwide. The wisdom of evacuating patients who may transmit the disease to new communities must be balanced with the need to contain the spread of the disease and the desires of family members to remain close to their relatives. This decision ultimately may have to be made by elected state or federal officials in the interest of national security.

Mass Fatality Management

A bioterrorist event is likely to produce significant numbers of fatalities, especially during the early phases of response. Local medical examiners, morgues, and funeral homes most likely will not be able to absorb the surge. Once activated and mobilized, the National Disaster Medical System includes a number of deployable Disaster Mortuary Operations Response Teams. At least one of these teams has additional training in handling contaminated or infected remains. Issues described below are involved with fatality management. [22]

Infection control

Enforce the same precautions required for live victims while handling deceased patients, during autopsy, and during disposal or disposition of the remains. Survivability of all potential pathogens in corpses has not been studied.

Victim identification and tracking

Even in a massive catastrophe, legal, moral, ethical, psychological, and religious reasons exist to identify the dead. Release or cremation of remains will be delayed unless positive identification occurs or, at a minimum, enough evidence is collected (eg, dental radiographs, fingerprints, photographs, potentially DNA samples) for determination later.

Establishment of temporary morgues

In the event of mass fatalities, the ability of hospitals and medical examiners to maintain all remains is doubtful. Without safeguards and training, local funeral homes may be resistant to accepting contaminated bodies. Processes must be in place prospectively to augment the existing system through the use of temporary morgues.

These sites require temperature and biohazard control, adequate water, lighting, rest facilities for staff, and viewing areas and should be in communication with patient tracking sites (probably the American Red Cross) and the emergency operations center.

Security also may be an issue.

Disposal or release of remains

Many moral, cultural, and religious issues are involved with disposal of the deceased. Although under a declared disaster, the governor and the President have extraordinary powers, at some point a decision must be made concerning the release of remains to families for interment or cremation or to the state for chemical cremation or incineration.

Develop appropriate plans and decision algorithms in advance.

Aftermath

Psychological issues

In any disaster, the tendency is to underplay the importance of addressing the psychological needs of the community—the victims and their families, survivors, and response personnel. Failure to address this important aspect of response and recovery impedes effective response during disaster operations and may have important long-term effects on the community well after recovery operations have been completed.

The loss of property or family members and friends under traumatic conditions is difficult at best, and disasters are no exception. When an entire community is affected by a disaster of any nature, the entire community may suffer short-term psychological effects, and a significant percentage of these individuals may develop posttraumatic stress disorder. Short-term mass crisis counseling may improve overall function and reduce the incidence of posttraumatic stress disorder among the population.

First responders and healthcare workers tend to deny their feelings and not deal with their own psychological trauma, especially during the actual crisis. Critical incident stress debriefing and interventional counseling for these personnel are required to reduce the incidence of long-term sequelae.

Legal and forensic issues

Superimposed on the ensuing disaster that a bioterrorist event creates are the myriad diverse legal and forensic issues that are involved in community response to the event. Many of these have not been resolved yet, at either the state or federal level, and, because of different state and local statutes, no standardized templates address them all.

During the planning process, address the major law enforcement and forensic issues that may affect healthcare operations, including the following:

-

Declaration and enforcement of quarantine

-

Legal requirements for community immunization or forced postexposure prophylaxis

-

Security at healthcare facilities, temporary morgues, neighborhood treatment centers, and antibiotic dispensing stations

-

Evidence collection (both physical and testimonial)

-

Patient privacy

-

Interstate licensing of providers and liability

Recovery from the event

In most disaster planning processes, the tendency is to focus on disaster response to the exclusion of recovery. A biological event does not cause physical destruction, and the community material resources remain intact. The 2 primary issues facing community governments and the local healthcare systems are environmental surety and long-term community mental health.

Most biological pathogens cited in bioterrorism research have very short life spans outside a host. Plague may become endemic among the rodent population of an area, posing a continued threat to the community. Anthrax spores have maintained viability under extreme environmental conditions for decades. Although not cited as a typical bioterrorist pathogen, the virus that causes animal foot-and-mouth disease is one of the hardiest known. Depending upon the pathogen released, ensuring that areas of high concentration are safe for use is necessary. Schools, auditoriums, or other sites used as inpatient expansion facilities require confirmation of contamination removal, if for no reasons other than legal liability and peace of mind of the community. This also may apply to traditional fixed site treatment facilities.

Should a major event occur, psychological problems would remain an issue for the community and possibly for the entire United States. An interesting anecdote from the Spanish influenza epidemic of 1918 is the paucity of literature or coverage of this disaster, both after the event and in historical documentation. A variety of reasons for this have been postulated, but estimates state that as much as one third of the population had a close friend or relative die from this epidemic. Apply the lessons learned in recent hurricanes, in which whole communities were displaced, to any community that suffers a bioterrorist attack.

Summary

A terrorist event presents unique challenges and obstacles to the healthcare system, well beyond those typically observed in US disasters. [16] Bioterrorism represents the most extreme example. [4] Material and human resource deficiencies at a time of greatly increased demand require unique and innovative solutions if death, disability, and major psychological impairment are to be ameliorated. Only through cooperative, comprehensive planning, across communities and vertically through all levels of government, is this able to be accomplished. [23, 24]

For patient education resources, visit the First Aid and Injuries Center. Also, see the patient education articles Biological Warfare and Personal Protective Equipment.

-

Chemical, Biological warfare training aboard USS Higgins. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

-

FEMA Hospital Emergency Response Training (HERT) for mass casualty incidents. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

-

Gram stained cerebrospinal fluid showing gram-positive anthrax baccilli (purple rods). Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.