Background

Hantavirus was first recognized as an infectious disease in the early 1950s when a cluster of 3,000 United Nation troops stationed in Korea was struck by a mysterious illness. [1] Ten to fifteen percent of those infected perished, [2] and though the exact etiologic agent was not discovered for 2 decades, it was suspected that rodents served as the main epidemiologic vector. Infection was associated with fever, hypotension, renal failure, thrombocytopenia, and disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC). The clinical syndrome became known as hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome (HFRS), formerly Korean hemorrhagic fever, and the virus was named Hanta after the Hantaan River of Korea. Over the ensuing years, several other etiologic agents of HFRS such as the Seoul, Puumala, and Dobrava viruses, were discovered across Europe and Asia. [3, 4, 5]

Though antigenic evidence of Hantavirus remains widespread among rodents across the United States, [6] only a handful of cases of HFRS was ever identified in the states. [7]

Hantavirus cardiopulmonary syndrome (HCPS), however, was not recognized until May of 1993, when an unusual illness struck a Navajo tribe living on the border of New Mexico and Arizona. [8] Those infected presented with fever, chills, myalgia, and cough, which often progressed to dyspnea, respiratory distress, and cardiovascular collapse. An alarming 80% of those infected died.

Over the next month, a highly effective collaboration ensued between the Indian Health Service, the University of New Mexico School of Medicine, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, leading not only to the successful isolation of the virus, but also to the identification of the reservoir and vector for the disease, Peromyscus maniculatus (deer mouse).

Serum samples from those afflicted demonstrated evidence of Hantavirus infection and within 10 weeks of the original outbreak, researchers had successfully developed a diagnostic test for the virus. The new virus went through a litany of names (eg, Little Water virus, Four Corners virus, Muerto Canyon virus) before finally being given the somewhat tongue-in-cheek moniker of Sin Nombre virus (in Spanish, literally the virus with no name). The clinical syndrome caused by Sin Nombre virus (SNV) became known as Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome (HPS) or, more accurately, Hantavirus cardiopulmonary syndrome (HCPS). [9]

About 20 viruses have been identified within the genus Hantavirus, family Bunyaviridae, but only 11 have been shown to cause human disease. Four of these belong to the “Old World” and cause HFRS across Europe and Asia. [9] China has the highest annual incidence of HFRS with somewhere between 20,000 and 100,000 cases of symptomatic HFRS reported each year. Most cases are attributable to the Seoul virus, with the Hantaan virus playing a more minor role.

Five of the “New World” Hantaviruses cause HCPS in North America, while a few others cause disease in Central America and South America. Most New World viruses cause HCPS only; however, the Black Creek Canal virus and the Bayou virus of the southeastern United States, as well as the Andes virus of South America, have been linked to renal failure and share some similarities with HFRS. SNV is the prototypical New World Hantavirus and is the cause of the vast majority of cases of HCPS in the United States.

The SNV and the Andes virus of South America cause the most severe disease, with case fatalities somewhere between 30% and 50%.

According to Native American legend, HCPS has existed in North America's southwest desert for hundreds, if not thousands, of years. Navajo oral tradition describes an illness now thought to be HCPS that struck down young healthy members of the tribe after temperate winters, and tradition also warns of the dangers of coexisting with rodents.

The earliest serologically confirmed SNV infection was in a person who developed an HCPS-like illness in July of 1959; scientists finally were able to confirm the presence of immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies to SNV in the victim’s serum in September of 1994. [9]

Pathophysiology

Each individual Hantavirus has its own natural host species of wild rodent as its reservoir [10] ; however, recent serologic testing of rodents has identified multiple new reservoir species. In the case of SNV, the primary reservoir is the deer mouse. Other recently identified reservoirs include the cactus mouse (Peromyscus eremicus) and the Cherries cane rat (Zygodontomys cherriei). [11, 12]

Somewhere between 5% and 20% of rodents exhibit antigenic evidence of Hantavirus infection with active viral shedding into feces, urine, and saliva. Human infection typically occurs by inhalation of aerosolized rodent waste, though occasionally disease may be contracted via a rodent bite or direct mucous membrane contact with rodent excreta. The primary risk factor for Hantavirus infection, therefore, is prolonged exposure to rodents, particularly within a closed, poorly ventilated area. [13, 14]

Although generally not transmittable from person-to-person, the Andes virus of Argentina is a surprising exception to this rule. [15] One Chilean study found that sexual partners of people with Andes virus–induced HCPS had a 17.6% risk of developing infection, as opposed to 1.2% among casual household contacts. [16]

Hantavirus demonstrates similar tissue tropism in rodents and humans, but for unclear reasons, rodents typically remain symptom free; consequently, they never develop immunity and become perpetual viral shedders. [17, 18] Given that Hantavirus typically is airborne, the virus first infects the lung parenchyma where it is phagocytized and transported to draining lymph nodes. From here, the virus disseminates and primarily targets vascular endothelial cells, particularly of the heart, lung, and lymphoid tissues, and in the case of HFRS, the kidney.

Hantaviruses have a single-stranded, negative-sense RNA genome, part of which encodes viral glycoproteins capable of attaching to beta-3-integrin cell surface molecules found on endothelial cells and platelets. [19] Although disease severity directly correlates with viral RNA load, [18] considerable evidence exists that immune mechanisms rather than direct viral cytopathology are responsible for the massive vascular dysfunction and plasma leakage of HFRS and HCPS. [20, 21] A 2014 study on SNV infection in rhesus macaques demonstrated a largely proinflammatory cytokine release leading to endothelial damage and subsequent HCPS-type symptomatology, suggesting a significant immune role in the disease progression. [22] Players implicated include tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF alpha), interleukin 1 beta (IL-1 beta), and interferon gamma (IFN-gamma), although this has yet to be clarified in humans. [23] Vascular endothelial growth factor has been implicated as a major player in the hyperpermeability found in Hantaan virus–induced HFRS. [24] It has been shown that an immune response precedes the development of the cardiopulmonary phase of the disease, lending additional credibility to the hypothesis of an immune-mediated pathogenesis. [9]

In the case of HCPS, capillary leak is overwhelmingly centered in the lungs leading to fulminant noncardiogenic pulmonary edema. Pathologic specimens demonstrate boggy, edematous lungs and copious tracheal and pleural fluid. [25] Histologic and immunohistochemical evidence also suggests a concomitant Hantavirus-induced myocarditis, which contributes to myocardial structural changes and dysfunction. [26] Patients may progress quickly to cardiogenic shock with decreased cardiac output, elevated systemic vascular resistance, and lactic acidosis. [27, 28] Severe cardiac depression acts synergistically with intravascular hypovolemia caused by capillary leakage and ultimately results in precipitous cardiopulmonary collapse. In light of this, early use of vasopressors and judicious administration of fluids is recommended, as well as the prompt transfer of patients to centers with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) capabilities in case rescue therapy becomes necessary. The name change from Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome to Hantavirus cardiopulmonary syndrome reflects the key contribution to morbidity made by concomitant myocardial dysfunction.

Epidemiology

Frequency

United States

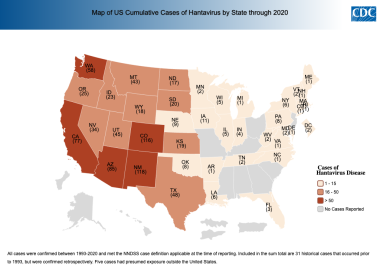

As of December 2020, 799 cases of Hantavirus cardiopulmonary syndrome (HCPS) had been confirmed in 40 states. Thirty-four percent of all reported cases have resulted in death.

Hantavirus disease by state of reporting. Cumulative case count through December 2020 per state based on data collected by the Nationally Notifiable Disease Surveillance System (NNDSS). Courtesy of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) [https://www.cdc.gov/hantavirus/surveillance/index.html].

Hantavirus disease by state of reporting. Cumulative case count through December 2020 per state based on data collected by the Nationally Notifiable Disease Surveillance System (NNDSS). Courtesy of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) [https://www.cdc.gov/hantavirus/surveillance/index.html].

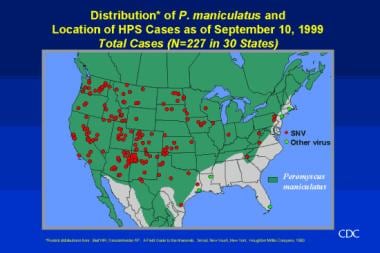

Most hantavirus disease cases in the United States are caused by the Sin Nombre virus (SNV) and have occurred west of the Mississippi River, which corresponds to the geographic distribution of the deer mouse. [9]

The preponderance of cases occurs in rural locales. The prevalence of Hantavirus infection in deer mice, the host vector for Sin Nombre virus, was 27.5-32.5%. The greatest concentration remains in the Four Corners area; the top 5 states of exposure are, in descending order, New Mexico, Colorado, Arizona, California, and Washington. National annual incidence in nonepidemic years is about 20-30 cases.

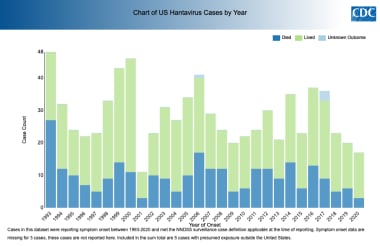

US Hantavirus Disease Cases Outcomes by Year. Courtesy of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) [https://www.cdc.gov/hantavirus/surveillance/index.html].

US Hantavirus Disease Cases Outcomes by Year. Courtesy of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) [https://www.cdc.gov/hantavirus/surveillance/index.html].

The New York virus, the Black Creek Canal virus, Seoul virus, and the Bayou virus are other rare causes of HCPS that have been confirmed in eastern and southeastern United States. [9]

Generally, outbreaks of Hantavirus occur in the spring and fall. An outbreak of HCPS struck campers at Yosemite National Park in summer 2012. Ten cases were confirmed in campers that slept in rodent-infested campsites; 3 of the 10 individuals died. [29] In January 2017, 24 patients were diagnosed with Seoul virus infection across 11 states; 3 people were hospitalized, and none died. [30]

International

Over 3000 cases of Hantavirus disease have been reported in the Americas collectively. Canada, primarily Alberta, reports around 10-15% of all North American cases annually. [31] In addition, Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Ecuador, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Uruguay, French Guiana, and Venezuela have all reported HCPS cases. [9] Currently, at least 4 Hantavirus species in South America are recognized to cause HCPS. One of them, the Andes virus, is unique for reports of person-to-person transmission and of an increased mortality rate in children. [9, 32, 33, 16]

Mortality/Morbidity

During the 1993 outbreak in the southwestern United States, the mortality rate was approximately 80%. Increased recognition of the disease and more aggressive interventions (eg, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) and early mechanical ventilation) have led to a decrease in mortality, with rates now ranging from 35% to 40%, though there is wide yearly variability. [9, 34, 35] Most deaths occur within 24 hours of hospital admission.

Race

During the initial outbreak in 1993, Native Americans were almost exclusively affected and the press named the mysterious disease "Navajo flu." As cases mounted, however, it became clear that HCPS was an equal opportunity killer. To date in the United States, 73% of patients with Hantavirus infection have been White; 17%, Native American; 1%, African Americans; 1%, Asian; and 20%, Hispanic (ethnicity considered separately from race). [9, 36]

Sex

Males account for 62% of the total number of HCPS diagnoses. This may reflect a higher environmental exposure to deer mice. [9]

Age

HCPS has a remarkable predilection for affecting relatively young, healthy adults. The mean age of patients with HCPS is 37 years, with a range of 6-83 years. Less than 7% of cases occur in persons younger than 17 years, and disease is very rare in those younger than 10 years. Preadolescent children infected with SNV have generally had mild illness; however, between May and November of 2009, a cluster of 5 severe pediatric cases was reported, resulting in 4 intubations and 1 case fatality. [37]

Prognosis

HCPS currently carries a case-mortality rate of 35-40% among adults. [38, 35] Preadolescents seem to experience a milder form of the disease and have significantly lower mortality.

Experiences with HCPS at the University of New Mexico Hospital have identified several factors that resulted in a 100% mortality rate in several patients who do not receive ECMO. [39] These include the following:

-

Cardiac index less than 2.5 L/min/m2

-

Ventricular tachycardia, ventricular fibrillation, or PEA

-

Hypotension despite adequate fluid resuscitation and vasoactive pressors

Patient Education

Educate patients and their families regarding the following:

-

Prodromal symptoms of HCPS

-

Risk of transmission by contact with rodents or rodent excreta

-

Techniques to safely clean-up infested areas

-

Rodent control measures (See Deterrence/Prevention.)

-

Hantavirus cardiopulmonary syndrome (HCPS) precautions during the 1993 outbreak.

-

Peromyscus maniculatus - The deer mouse.

-

Geographic distribution and viral cause of Hantavirus cardiopulmonary syndrome (HCPS).

-

Geographic distribution of Hantavirus cardiopulmonary syndrome (HCPS) and Peromyscus maniculatus.

-

Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome cases by outcome.

-

Hantavirus cardiopulmonary syndrome (HCPS) immunoblast.

-

Chest radiographic progression of Hantavirus cardiopulmonary syndrome (HCPS).

-

Clinical progression of hantavirus cardiopulmonary syndrome.

-

Hantavirus disease by state of reporting. Cumulative case count through December 2020 per state based on data collected by the Nationally Notifiable Disease Surveillance System (NNDSS). Courtesy of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) [https://www.cdc.gov/hantavirus/surveillance/index.html].

-

US Hantavirus Disease Cases Outcomes by Year. Courtesy of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) [https://www.cdc.gov/hantavirus/surveillance/index.html].