Practice Essentials

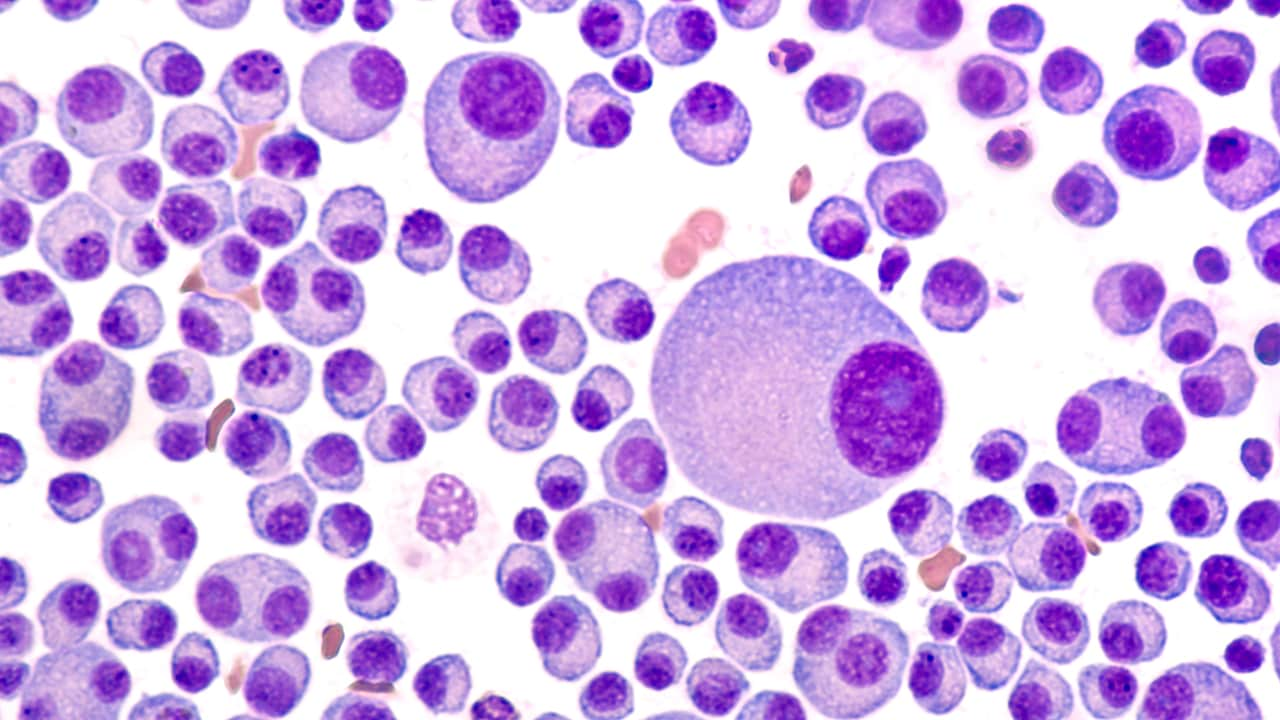

Hyperviscosity syndrome (HVS) refers to the clinical sequelae of increased blood viscosity. Increased serum viscosity usually results from increased circulating serum immunoglobulins and can be seen in such diseases as Waldenström macroglobulinemia and multiple myeloma. [1, 2] HVS can also result from increased cellular blood components (typically white or red blood cells) in hyperproliferative states such as the leukemias, polycythemia, and the myeloproliferative disorders.

The clinical presentation in HVS consists principally of the triad of mucosal bleeding, visual changes, and neurologic symptoms. [3, 4] Constitutional symptoms and cardiorespiratory symptoms may also occur.

The diagnosis of HVS is confirmed by measurement of elevated serum viscosity in a patient with characteristic clinical manifestations of HVS. No exact diagnostic cut-off exists for serum viscosity, however, as different patients will have symptoms at different values.

Plasmapheresis is the treatment of choice for initial management and stabilization of HVS from elevated immunoglobulin levels. [5] Leukapheresis, plateletpheresis, and phlebotomy are indicated for HVS from leukostasis, thrombocytosis, and polycythemia, respectively.

Definitive treatment of HVS is treatment of the underlying disorder (eg, chemotherapy). If the underlying disease process is left untreated, the hyperviscosity will recur.

Pathophysiology

Viscosity is a property of liquid and is described as the resistance that a liquid exhibits to the flow of one layer over another. As serum proteins or cellular components increase, the blood becomes more viscous. Vascular stasis and resultant hypoperfusion then lead to the clinical symptoms of hyperviscosity syndrome (HVS).

The normal relative serum viscosity ranges from 1.4-1.8 units (reported as Centipoises). Symptoms usually are not seen at viscosities of less than 4 units, and HVS typically requires a viscosity greater than 5 units.

HVS is associated most commonly with plasma cell dyscrasias [6] (the paraproteinemias) and is due to the large size of the excess immunoglobulin M (IgM) paraproteins in these disorders. Waldenström macroglobulinemia is the most common cause and accounts for about 85% of cases of HVS. Less frequently, HVS can occur in multiple myeloma (especially with myeloma proteins of the IgA and IgG3 types) and connective tissue diseases. Chen and colleagues describe seven cases of polyclonal HVS caused by IgG4-related disease. [7]

HVS can also be caused by the bone marrow hyperproliferative states, as follows:

-

Leukemia

-

Polycythemia

-

Essential thrombocytosis

-

Myelodysplastic disorders

Confusion and mental status changes result from the increased viscosity of the blood and decreased cerebral blood flow. This sludging leads to segmental dilatation of retinal veins and retinal hemorrhages. Mucosal bleeding may occur from prolonged bleeding time caused by myeloma proteins interfering with platelet function.

Cardiopulmonary symptoms such as shortness of breath, hypoxemia, acute respiratory failure, and hypotension also result from this sludging of blood and decreased microvascular circulation.

Clinical sequelae of HVS can include congestive heart failure, ischemic acute tubular necrosis, and pulmonary edema with multiorgan system failure and death if treatment is not promptly initiated. [8] Thus, prompt recognition and expeditious treatment are imperative in preventing deterioration. [4]

Epidemiology

Little epidemiologic information is available on hyperviscosity symdrome. One study found that 61% of blood dyscrasias occur in males. Most blood dyscrasias are not diagnosed until the seventh decade of life. Mortality is related to the underlying cause of the hyperviscosity syndrome.