Background

Trichinellosis, also known as trichinosis (Trich from Greek thrix meaning hair), is an infection caused by nematodes of the genus Trichinella, most commonly T spiralis in humans. Through historical, paleopathologic, and, most recently, genomic studies, the complex, intertwined history of humans, their food, and this worm has become better defined. Genomic evidence suggests the presence of Trichinella as a distinct species since some time in the mid to latter Miocene period (around 20 million years ago). [1] To date, 10 distinct species and 3 genotypes in 2 clads, encapsulated and nonencapsulated, have been found to infect mammals, birds, and reptiles around the globe, though not all have been found to infect humans. [2]

The earliest human infection is reported to have been documented in an Egyptian mummy that dates to approximately 1300 BCE. [3] Religious injunctions on the consumption of pork may reflect early cultural awareness of this human-animal infection link. [4]

The first modern scientific observations of human Trichinella infection, from the autopsy of a man with "sandy diaphragm," were reported by medical student James Paget (of Paget disease) to a medical student society and published by his lecturer in clinical anatomy, Sir Richard Owen, then assistant curator at the Royal College of Surgeons. [3] The initial life cycle was worked out by Rudolf Virchow and associates over the years 1850-1870. [5]

By the 1860s, trichinellosis was well-recognized as a disorder spread through infected pigs, leading to a cultural aversion to certain pork products, particularly German and Dutch sausage. [6]

Geopolitical and cultural factors, such as increases in global movement of food products and persons, particularly with various exotic tourism activities, evolving into the 21st century are leading to a resurgence of human infections in areas that have been free of infection for decades. [7] Climate change and appearance of carnivorous and omnivorous species in new regions is having an influence on distribution of the various Trichinella species. [79] These changes in the distribution of the various trichinellae and the attendant risk of consumption has particular relevance to Emergency Medicine because people may present to emergency departments in areas with little or no presence of trichinellosis locally, having contracted it while travelling, and because early diagnosis is associated with improved treatment outcomes.

Early diagnosis depends on clinician awareness and uncovering relevant patient history since the initial clinical presentation may be nonspecific.

Causes

Trichinellosis is a completely preventable infestation. The single most important causative factor is the consumption of inadequately cooked, infected meat. Although most developed countries have some form of trichinella control program for commercially produced pork, these controls have been documented to fail. [26]

Trichinella species of nematodes: Of the 13 recognized species and genotypes, the following are the most clinically significant, although others may not yet have been identified or found in human infections:

-

T spiralis is the primary cause associated with domesticated animals.

-

T britovi is seen frequently in wild boar, horses, and free-ranging swine. It also has been reported in bear in Japan where it has been given a separate classification, T9, because of minor genetic variations from the European T britova. [14]

-

T murrelli has been identified in wild and domestic animals other than pigs only in North America. [49]

-

T nelsoni is seen in various large carnivores of sub-Saharan Africa. [24]

-

T nativa has been documented in almost all land and marine mammalian carnivores in the arctic and periarctic regions around the globe. In humans, it has been associated with more prolonged diarrhea and fewer muscle symptoms. It is more resistant to freezing than other species, having been documented to not be killed by prolonged freezing at -18o C. [49]

-

T9, closely related to T britovi, is isolated to Japan, existing in bear, fox, and raccoon dog. [49]

-

T pseudospiralis has been documented in birds and does not form a capsule in the muscle, thus leading to less muscle inflammation and pain. Conversely, the muscle phase seems to remain actively infective for a longer period, probably since, without cyst formation, ultimate calcification does not occur. [62]

-

T papuae in wild pigs has been identified in Papua-New Guinea as a source of infection among forest-dwelling hunters. It is a nonencapsulating form of Trichinella. [53]

Pathophysiology

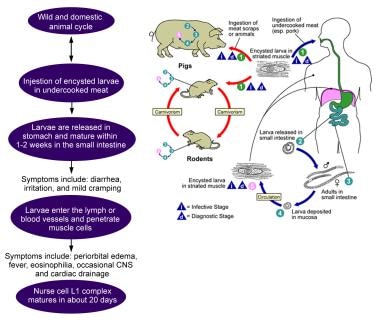

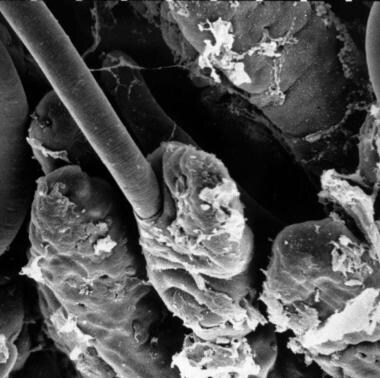

Infection is initiated by ingestion of viable larvae in raw or undercooked meat. Digestive action, largely due to pepsin and hydrochloric acid, liberates the larvae. The liberated larvae are activated by exposure to bile salts. [86] They then invade columnar epithelial cells in the duodenum and jejunum (see image), most probably through chemical means since structures for physical penetration of cell walls have not been described. The larvae have been observed to pass from cell to cell, including extending across more than one cell at a time, leaving a trail of dead cells behind them. [87, 88] During this phase they undergo 4 molts over less than 2 days to become sexually differentiated adults, after which they mate. [89] The adult males then die and are expelled. Beginning around 4-5 days after ingestion, females begin liberating live larvae, referred to as newborn larvae (NBL), with each female producing around 1,500 NBL. [90] The damaged intestinal cells die and are passed out in stool.

T spiralis larva entering intestinal columnar epithelial cell. Courtesy of Ken Wright [The Trichinella Page at https://www.trichinella.org/gallery].

T spiralis larva entering intestinal columnar epithelial cell. Courtesy of Ken Wright [The Trichinella Page at https://www.trichinella.org/gallery].

Contrary to the ingested larvae, newborn larvae are able to penetrate the intestinal wall and enter the lymphatic system, from where they enter the bloodstream and disperse to areas of implantation. Newborn larvae have been implicated in cardiac and neurologic aspects of the disease. [80] Myocardial involvement appears to be primarily due to an eosinophilic myocarditis with associated pericarditis and myocardial dysfunction leading to congestive heart failure in more severe cases. [85] Central nervous system effects have been described as either meningeal or parenchymal. Eosinophilia-associated effects related to their inflammatory process role have been implicated as the most likely basis for these dysfunctions. [80]

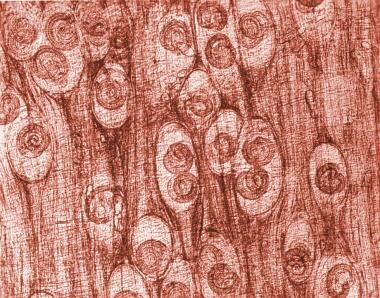

Although the presence of larvae provokes eosinophilia, they are generally resistant to any immunologic reaction from the host as they migrate out of the capillaries and, with the aid of a stylet, penetrate muscle cells. Once in the cell, they alter cellular activity to turn the individual cells into "nurse cells." To nourish themselves in the nurse cell, the larvae stimulate angiogenesis leading to formation of a capillary rete around the invaded muscle cell. [8] Additionally, the normal cell life cycle of the invaded muscle cell enters a permanent arrest, with nuclear DNA remaining for the remainder of the life of the host at the G2/M phase transition. [9] Nurse cell formation also has been demonstrated to have many features analogous to muscle cell repair. [10]

Photomicrograph depicting numbers of Trichinella spiralis cysts seen embedded in a muscle tissue specimen, in a case of trichinellosis. Image courtesy of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Photomicrograph depicting numbers of Trichinella spiralis cysts seen embedded in a muscle tissue specimen, in a case of trichinellosis. Image courtesy of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

A distinguishing feature between two general subclassifications (clads) of Trichinella species is whether the nurse cell forms a collagen capsule. [11]

The direct trauma of the larva encysting in muscle cells, coupled with the immunologic response, is responsible for other clinical features (eg, fever, myalgias). Typically, the intramuscular cysts eventually calcify. (See the image below.) Encysted larvae are able to survive in deceased hosts by entering a stage of anaerobic metabolism that may last years depending on the ambient temperature. [79]

As an aside in the study of the interaction of Trichinella with its host, an anti-cancer effect has been demonstrated both in vitro and in mouse cancer models. [82] This effect and the manner in which the larvae interact with the immune system to not be attacked by host protective mechanisms are fields of developing research to understand if these reactions might be harnessed in other human conditions such as autoimmune disorders and transplantation. [83, 84] Additionally, growing awareness regarding symbiotic relationships between humans and various organisms to which they are exposed, referred to as the “Hygiene Hypothesis,” has led to research focused on the relationship of helminth infections, including trichinellosis, with immunologically mediated diseases such as type 2 diabetes mellitus. [97, 98]

Epidemiology

Frequency

United States

Documented occurrence in the United States is largely limited to sporadic cases or small clusters related to consumption of home-processed meats from noncommercial farm-raised pigs and wild game. [14] Trichinellosis has been a reportable disease since 1966. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) surveillance system has data as far back as 1947 demonstrating a significant decrease in cases from a peak of nearly 500 in 1948 to a total of 13 cases reported from all states in 2015, the latest data available as of 2023. [14] Human migratory patterns may also contribute to sporadic cases as demonstrated by a report of a Laotian immigrant to the United States developing trichinellosis after consuming lightly cooked commercially purchased pork. [15]

The rising interest in “free ranging” agriculture has led to concern about an increase in infected pork. [79, 100]

Hunters and others who eat carnivorous game continue to be at risk, with the large majority of cases reported in the United States over the past 20 years being among persons who have consumed lightly cooked wild game, most commonly bear and wild boar. [14]

International

Reliable data on the incidence of trichinellosis varies around the world for several reasons. Initial clinical features of the disease overlap with other, more benign disorders, such as simple gastroenteritis. Characteristic signs of palpebral edema may not be recognized as representative of illness. Muscle pains from encysting of larvae may be delayed. In many parts of the world, for reasons ranging from difficult access to health care to poor public health reporting systems, presence of trichinosis may not be well documented unless occurring in clusters of cases. [21]

Overall international incidence of trichinellosis associated with commercially produced pork consumption has significantly decreased since 2000. [101] The incidence of infection from consuming commercially produced pork in Europe has significantly decreased over the past 20 years, though there remain sporadic case clusters, typically associated with pork from small producers who may not be practicing optimal techniques of protection of their herds. [102] Additionally, increased interest in “free-ranging” meat production increases the risk for infection of pigs. [101] In other parts of the world, the reporting is variable, though the patterns of exposure are similar, small farm raising of pigs, lack of attention to thorough cooking of pork, and consumption of wild carnivores. [103]

Although cases have become rare in countries with laws and education aimed at limiting the feeding of raw garbage or animal byproducts to commercially raised pigs along with well-managed slaughterhouse surveillance systems, many countries have passed laws but fallen short on the implementation and quality assurance of the programs and continue to have more cases related to consumption of non-wildlife meat. [25, 102, 26] The cost of surveillance programs can be high and complex to install because of education and cultural issues. [16]

The International Commission on Trichinellosis, with representation from more than 40 countries, has developed a set of guidelines that are reviewed and updated at quadrennial scientific and policy meetings. [26, 105] Researchers are constantly seeking less cumbersome and costly methods of testing animal muscle tissue. [26]

Home raising of pigs, with feeding of raw garbage instead of grain, is still a common practice in a large part of the world at all levels of development. In many countries, pigs roam freely, leading to contact with sylvatic sources of infection. Celebration of the Thai New Year has been associated with 200-600 cases in a single year and is a known annual source of multiple cases. [27, 28] Group tourist travel also has been associated with cluster outbreaks. [29] In several Southeast Asian countries, raw pork sausage and other dishes are considered delicacies and are regularly associated with outbreaks.

Trichinellosis must be considered a risk when eating the flesh of any animal that might have fed on uncooked animal flesh. Many animals generally not considered carnivorous will eat meat products when presented in a form they can chew, that is, usually chopped, or ground and combined with vegetable matter. This most commonly occurs on small farms when animals are fed table scraps or the scraps from butchering another farm animal. Rats also represent a reservoir in settings where raw animal scraps are left out for domestic animals to eat.

Market changes with international movement of processed food ingredients through either commercial channels or individual transport of products have presented a new source of difficulty in control. Two case clusters from Germany in 1998 were related to commercially produced sausage produced from meat transported from several different countries in Europe. [30] A 2007 outbreak in Poland with more than 180 confirmed cases was linked to one manufacturer of low-priced sausage. This outbreak even spread to Germany as cross-border shoppers returned with lower-priced sausage from the same Polish region. [31] Other clusters have occurred in relation to immigrant families bringing home-country delicacies back from vacation to their new countries of residence. [32, 33, 34]

Travelers to regions with significant amounts of small-farm pig raising are strongly advised to consider any pork products to be suspect and to avoid consumption of any pork sausage. If eating pork or unidentified meat, adequate cooking should be personally verified. An outbreak in Turkey, a largely Muslim country, was attributed to an unscrupulous producer of meatballs adding pork from unverified farms to the beef and selling the meatballs as pure beef. [39]

Although generally thought of as a disease of omnivorous or carnivorous animals, herbivores have demonstrated infection, most likely from prepared feed that contained remnants of infected animals. In France, horse meat, largely imported, led to more than a dozen outbreaks involving more than 3000 human victims between 1975 and 2005. [79] Interestingly, the same meat exporting countries supply various other European Union countries that have no human trichinellosis; unlike the French and Italians, those countries do not have the culinary habit of eating raw or minimally cooked meat. [40]

China has some of the highest recorded case numbers globally. [41] Serologic population surveys have revealed prevalence rates of between 0.66 and 12%, varying somewhat from among regions depending on eating habits. Yunan province was found to be the most significantly affected province. Pigs are the primary vector with prevalence rates as high as 50% in slaughterhouse surveys in some provinces. [42] The Western Region Development strategy of the 1990s led to many people from the endemic regions of central and eastern China migrating with infected livestock to regions with previously very low incidence. An increased demand from tourist industry development has led to an increase in small producers using uncooked swill to feed pigs and not confining the pigs from wild vectors with a concomitant increase in pig prevalence to as high as 100% reported in one region. [43]

Arctic and subarctic mammals (polar bear, walrus, seal) have been identified as being vectors for Trichinella nativa, which may also infect humans. [44] 45 T nativa is resistant to freezing, even for months at -20o C. Up to 60% of polar bears in Nunavik have been found to be infected. [46] Some Inuit have adjusted eating habits to avoid old male walruses as they are primarily scavengers, whereas the young feed primarily on shellfish. [47]

Consumption of wild boar prepared into sausage in Spain has led to human infection with T britovi in Spain and Sweden. [48] Wild boar also have been identified as a source of human infection in other areas in the Mediterranean basin, southeast Asia, and Pacific Islands. [49]

In recent years, the effect of consumer trends such as greater interest in "free ranging" meats has been associated with a higher incidence of trichinellosis among pigs raised in these settings in the United States [50] and Europe. [51] The European Union has implemented a Trichinella monitoring program. [52] The United States relies on visual inspections in slaughterhouses, without specific focus on Trichinella infection, accompanied by regulations governing the food sources of pigs whose meat is destined to commercial markets.

This rather extensive listing of international incidence of animal and human infection has been presented to offer some direct information regarding areas of particular concern as well as to further make the point of the importance of dietary and travel history in patients with gastroenteritis, particularly with associated eosinophilia or palpebral edema.

Mortality/Morbidity

Specific death rate information is not established. Death is rare without development of neurologic or cardiac involvement.

Although most patients with muscle involvement have resolution of pain and associated disability, some may experience persistent myalgia and fatigue. In severe infections (very high larval load) muscle weakness may be enough to significantly impair mobility.

Following neurologic or cardiac involvement, persistent variable dysfunction of either system may develop, depending upon the distribution of lesions.

Race

Trichinella infection does not vary among different races. Variations in disease presence are based more on cultural food preparation and consumption practices.

Sex

Incidence is equal in males and females unless particular culinary habits lead to higher exposure for one group. [53]

There is evidence that pregnancy may offer some protection against infection. [54]

Age

All age groups reportedly have been affected; however, trichinellosis most commonly occurs in persons aged 20-49 years, mostly related to eating habits around wild game.

Serologic evidence for potential transplacental migration of larvae demonstrated though direct evidence of presence of larvae has only been reported in different animals and in one case report of a fetus from a therapeutic abortion of an infected mother. [54, 55, 56, 122]

Prognosis

Unless experiencing a very high load of ingested larvae with the attendant risk for cardiac and neurologic sequelae, persons who are treated with anthelminthics and, when indicated, corticosteroids, usually fully recover.

Full recovery is variable if cardiac or neurologic involvement occurs.

Patient Education

The primary educational message is that all meat from animals that may have eaten either live or dead animal meat should only be consumed well cooked. The USDA recommends that solid pieces of pork (steaks, chops, and roasts) be cooked to an internal temperature of 145 deg F (63 deg C) and that ground pork and other body part dishes be cooked to 160 deg F (71 deg C). [111]

-

Life cycle of Trichinella species parasite. Image courtesy of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

-

Photomicrograph depicting numbers of Trichinella spiralis cysts seen embedded in a muscle tissue specimen, in a case of trichinellosis. Image courtesy of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

-

T spiralis larva entering intestinal columnar epithelial cell. Courtesy of Ken Wright [The Trichinella Page at https://www.trichinella.org/gallery].