Practice Essentials

Retinal detachment (see the image below) refers to separation of the inner layers of the retina from the underlying retinal pigment epithelium (RPE, choroid). Next to central retinal artery occlusion, chemical burns to the eye, and endophthalmitis, it is one of the most time-critical eye emergencies encountered in the emergency setting.

Signs and symptoms

Symptoms of retinal detachment may include the following:

-

Photopsia (common initially)

-

Visual field defect (developing over time; may help localize detachment)

-

Floaters

The history should include inquiries into the following:

-

History of trauma

-

Previous ophthalmologic surgery

-

Previous eye conditions (eg, uveitis and vitreous hemorrhage)

-

Duration of visual symptoms and visual loss

Physical examination should include the following:

-

Checking of visual acuity

-

External examination for signs of trauma and checking of the visual field

-

Assessment of pupil reaction

-

Measurement of intraocular pressure in both eyes

-

Slit-lamp biomicroscopy

-

Examination of the vitreous for signs of pigment or tobacco dust

-

Examination of the dilated fundus with ophthalmoscopy (preferably indirect)

See Presentation for more detail.

Diagnosis

Retinal detachment occurs by 3 basic mechanisms and thus is classified into the following 3 main types:

-

Rhegmatogenous retinal detachment (the most common type) – This results when a hole, tear, or break in the neuronal layer allows fluid from the vitreous to seep between and separate sensory and RPE layers

-

Traction retinal detachment – This results from adhesions between the vitreous gel/fibrovascular proliferation and the retina

-

Exudative (serous) retinal detachment – This results from exudation of material into the subretinal space from retinal vessels (as in hypertension, central retinal venous occlusion, vasculitis, or papilledema)

Laboratory tests are not helpful in detecting retinal detachment, but basic blood work may be useful if the patient requires surgical intervention.

Unless globe rupture, orbital/facial bone fractures, or intraocular foreign bodies are suspected, diagnostic imaging is not warranted.

See Overview and Workup for more detail.

Management

General treatment measures include the following:

-

Nil per os (NPO) status in anticipation of retinal surgery

-

In trauma cases, protection of the globe with a metallic eye shield

-

Avoidance of any pressure on the globe

-

Limitation of activity to a minimum until further evaluation

-

Treatment of any unstable vital signs in preparation for possible emergency surgery

-

Consideration of referral to a retina specialist (eg, whenever a macula-on retinal detachment is suspected)

Specific techniques for treating retinal detachments include the following:

-

Scleral buckling

-

Pars plana vitrectomy

-

Pneumatic retinopexy

Retinal detachment repair is usually done on an outpatient basis.

See Treatment and Medication for more detail.

Background

Next to central retinal artery occlusion, chemical burns to the eye, and endophthalmitis, a retinal detachment is one of the most time-critical eye emergencies encountered in the ED. Retinal detachment (RD) was first recognized in the early 1700s by de Saint-Yves, but clinical diagnosis remained elusive until Helmholtz invented the ophthalmoscope in 1851.

Tragically, retinal detachments were uniformly blinding until the 1920s when Jules Gonin, MD, pioneered the first repair of retinal detachments in Lausanne, Switzerland. Today, with the advent of scleral buckling and small-gauge pars plana vitrectomy, in addition to laser and cryotherapy techniques, rapid ED diagnosis and treatment of a retinal detachment truly can be a vision-saving opportunity.

Pathophysiology

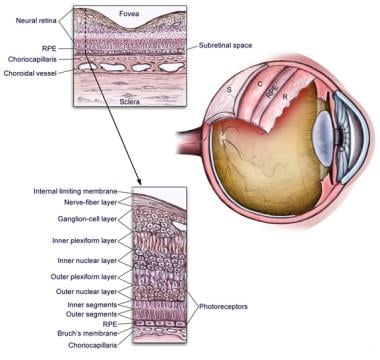

Eye anatomy is shown in the image below.

Retinal detachment refers to separation of the inner layers of the retina from the underlying retinal pigment epithelium (RPE, choroid). The choroid is a vascular membrane containing large branched pigment cells sandwiched between the retina and sclera. Separation of the sensory retina from the underlying RPE occurs by the following 3 basic mechanisms:

-

A hole, tear, or break in the neuronal layer allowing fluid from the vitreous cavity to seep in between and separate sensory and RPE layers (ie, rhegmatogenous retinal detachment)

-

Traction from inflammatory or vascular fibrous membranes on the surface of the retina, which tether to the vitreous

-

Exudation of material into the subretinal space from retinal vessels such as in hypertension, central retinal venous occlusion, vasculitis, or papilledema

Retinal detachments may be associated with congenital malformations, metabolic disorders, trauma (including previous ocular surgery), [1] vascular disease, choroidal tumors, high myopia or vitreous disease, or degeneration.

Of the 3 types of retinal detachment, rhegmatogenous RD is the most common, deriving its name from rhegma, meaning rent or break. Vitreous fluid enters the break and separates the sensory retina from the underlying RPE, resulting in detachment. [2]

Exudative or serous detachments occur when subretinal fluid accumulates and causes detachment without any corresponding break in the retina. The etiologic factors are often tumor growth or inflammation. These types of retinal detachment do not usually require surgical intervention. Correction of the underlying disorder typically leads to resolution of these detachments.

Tractional retinal detachment occurs as a result of adhesions between the vitreous gel/fibrovascular proliferation and the retina. Mechanical forces cause the separation of the retina from the RPE without a retinal break. Advanced adhesion may result in the eventual development of a tear or break. The most common causes of tractional retinal detachment are proliferative diabetic retinopathy, sickle cell disease, advanced retinopathy of prematurity, and penetrating trauma.

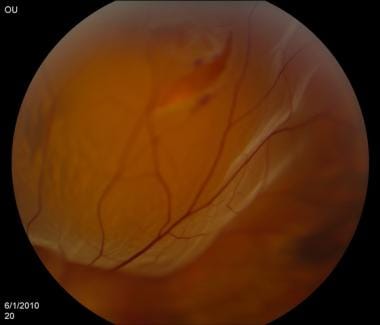

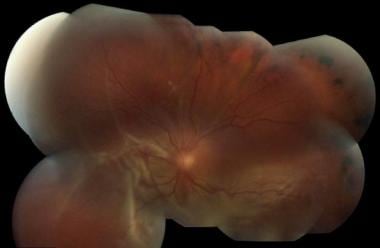

Retinal detachments are shown in the images below.

Epidemiology

Frequency

United States

Although 6% of the general population are thought to have retinal breaks, most of these are asymptomatic benign atrophic holes, which are without accompanying pathology and do not lead to retinal detachment. The annual incidence is approximately one in 10,000 or about 1 in 300 over a lifetime. [2] Other sources suggest that the age-adjusted incidence of idiopathic retinal detachments is approximately 12.5 cases per 100,000 per year, or about 28,000 cases per year in the US. [3]

Certain groups have higher prevalence than others. Patients with high myopia (>6 diopters) and individuals with aphakia (ie, cataract removal without lens implant) have a higher risk. Cataract extraction complicated by vitreous loss during surgery can have an increased detachment rate of up to 10%.

International

The most common worldwide etiologic factors associated with retinal detachment are myopia (ie, nearsightedness), aphakia, pseudophakia (ie, cataract removal with lens implant), and trauma. Approximately 40-50% of all patients with detachments have myopia, 30-40% have undergone cataract removal, and 10-20% have encountered direct ocular trauma. Traumatic detachments are more common in young persons, and myopic detachment occurs most commonly in persons aged 25-45 years. Although no studies are available to estimate incidence of retinal detachment related to contact sports, specific sports (eg, boxing) have an increased risk of retinal detachment.

Mortality/Morbidity

Estimates reveal that 15% of people with retinal detachments in one eye develop detachment in the other eye. Risk of bilateral detachment is increased (25-30%) in patients who have had bilateral cataract extraction.

Race

There exists no racial predilection for retinal detachment incidence.

Sex

There exists no gender predilection for retinal detachment incidence.

Age

As the population ages, retinal detachments (RDs) are becoming more common. Retinal detachment usually occurs in persons aged 40-70 years. However, paintball injuries in young children and teens are becoming increasingly common causes of eye injuries, including traumatic retinal detachments.

Prognosis

As the retina is neuro-sensitive tissue, visual prognosis can be difficult to predict. Generally, a retinal detachment without macular involvement tends to have a better final visual prognosis.

-

Anatomy of the eye.

-

Retinal detachment. Courtesy of Kresge Eye Institute, Detroit, Michigan.

-

Retinal detachment. Courtesy of Kresge Eye Institute, Detroit, Michigan.

-

Retinal detachment. Courtesy of Kresge Eye Institute, Detroit, Michigan.

-

Retinal detachment. Courtesy of Kresge Eye Institute, Detroit, Michigan.

-

Retinal detachment. Courtesy of Kresge Eye Institute, Detroit, Michigan.

-

Retinal detachment. Courtesy of Kresge Eye Institute, Detroit, Michigan.

-

Sonogram of retinal detachment. Courtesy of Bruce Lo, MD.