Practice Essentials

Pharyngitis is defined as an infection or irritation of the pharynx or tonsils (see the image below). The etiology is usually infectious, with most cases being of viral origin and most bacterial cases attributable to group A streptococci (GAS). Other causes include allergy, trauma, toxins, and neoplasia. The group A beta-hemolytic streptococcal (GABHS) rapid antigen detection test is the preferred method for diagnosing GAS infection in the emergency department because of difficulties with culture follow-up. [1]

Posterior pharynx with petechiae and exudates in a 12-year-old girl. Both the rapid antigen detection test and throat culture were positive for group A beta-hemolytic streptococci.

Posterior pharynx with petechiae and exudates in a 12-year-old girl. Both the rapid antigen detection test and throat culture were positive for group A beta-hemolytic streptococci.

Signs and symptoms

It is difficult to distinguish viral and bacterial causes of pharyngitis on the basis of history and physical examination alone. Nevertheless, the following factors may help rule out or diagnose GAS pharyngitis:

-

GAS infection is most common in children aged 4-7 years

-

Sudden onset is consistent with GAS pharyngitis; pharyngitis after several days of coughing or rhinorrhea is more consistent with a viral etiology

-

Contact with others who have GAS or rheumatic fever with symptoms consistent with GAS raises the likelihood of GAS pharyngitis

-

Headache is consistent with GAS infection

-

Cough is not usually associated with GAS infection

-

Vomiting is associated with GAS infection, though not exclusively so

-

Recent orogenital contact suggests possible gonococcal pharyngitis

-

A history of rheumatic fever is important

Centor criteria for GAS pharyngitis include the following:

-

Fever (1 point)

-

Anterior cervical lymphadenopathy (1 point)

-

Tonsillar exudate (1 point)

-

Absence of cough (1 point)

A score of 0-1 makes GAS infection unlikely; a score of 4 makes it likely. In adults, the positive predictive value of these criteria is around 40% if 3 criteria are met and about 50% if 4 criteria are met.

Physical examination includes the following:

-

Assessment of airway patency

-

Temperature

-

Hydration status

-

Head, ears, eyes, nose, and throat – Conjunctivitis, scleral icterus, rhinorrhea, tonsillopharyngeal/palatal petechiae, tonsillopharyngeal exudate, oropharyngeal vesicular lesions

-

Lymphadenopathy (cervical or generalized)

-

Cardiovascular evaluation

-

Pulmonary assessment

-

Abdominal examination

-

Skin examination

See Clinical Presentation for more detail.

Diagnosis

Laboratory studies that may be helpful include the following:

-

Group A beta-hemolytic streptococcal rapid antigen detection test (preferred diagnostic method in emergency settings)

-

Throat culture (criterion standard for diagnosis of GAS infection [90-99% sensitive])

-

Mono spot (up to 95% sensitive in children; less than 60% sensitive in infants)

-

Peripheral smear

-

Gonococcal culture if indicated by the history

Imaging studies generally are not indicated for uncomplicated viral or streptococcal pharyngitis. However, the following may be considered:

-

Lateral neck film in patients with suspected epiglottitis or airway compromise

-

Soft-tissue neck CT if concern for abscess or deep-space infection exists

A throat swab may also be done.

See Workup for more detail.

Management

Prehospital care usually is not necessary for uncomplicated pharyngitis unless airway compromise is an issue. Intubation should not be attempted unless the patient stops breathing spontaneously.

Emergency measures may include the following:

-

Assess and secure the airway, if necessary

-

Assess the patient for signs of toxicity, epiglottitis, or oropharyngeal abscess

-

Evaluate hydration status, and rehydrate as necessary

-

Assess for GAS infection if clinically suspected

Most cases, whether viral or bacterial, are relatively benign and self-limited. Management of GAS infection, when indicated, includes the following:

-

Do not treat patients without a positive culture or positive rapid antigen detection test result

-

Perform a rapid antigen detection test if GAS is clinically suspected on the basis of the history and physical examination; if test results are positive, begin antibiotic therapy

-

Patients with a low Centor score (0-1) can often be treated symptomatically for pharyngitis without further testing for GAS

-

Patients with a Centor score of 4 should have confirmation of GAS infection with an antigen test before being treated with antibiotics, unless such testing is unavailable

-

Household contacts of patients with GAS infection or scarlet fever should be treated for a full 10 days of antibiotics without testing only if they have symptoms consistent with GAS; asymptomatic contacts should not be treated

-

If the diagnosis is in doubt or the above criteria are not met, initiation of antibiotic therapy should await rapid antigen test or culture results

See Treatment and Medication for more detail.

Background

Pharyngitis is defined as an infection or irritation of the pharynx and/or tonsils. The etiology is usually infectious, with most cases being of viral origin. These cases are benign and self-limiting for the most part. Bacterial causes of pharyngitis are also self-limiting, but are concerning because of suppurative and nonsuppurative complications. Other causes include allergy, trauma, toxins, and neoplasia. [2]

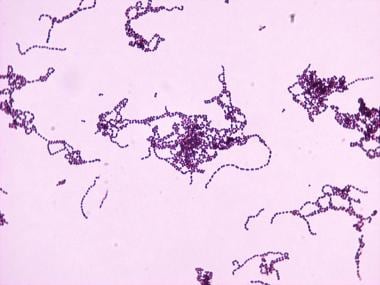

The most significant bacterial agent causing pharyngitis in both adults and children is GAS infection (Streptococcus pyogenes); this is shown in the image below.

Physical findings of GAS are shown in the image below.

Posterior pharynx with petechiae and exudates in a 12-year-old girl. Both the rapid antigen detection test and throat culture were positive for group A beta-hemolytic streptococci.

Posterior pharynx with petechiae and exudates in a 12-year-old girl. Both the rapid antigen detection test and throat culture were positive for group A beta-hemolytic streptococci.

Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Chlamydia pneumoniae, and Arcanobacterium haemolyticus are other bacterial causes of pharyngitis, but these pathogens are rare. Antibiotics covering atypical pathogens should not routinely be used to treat pharyngitis. [3]

The main ED concerns with pharyngitis are to rule out more serious conditions, such as epiglottitis or peritonsillar abscess, and to diagnose group A beta-hemolytic streptococcal (GABHS) infections. Airway obstruction is also of utmost importance for the ED physician treating pharyngitis.

Pathophysiology

With infectious pharyngitis, bacteria or viruses may directly invade the pharyngeal mucosa, causing a local inflammatory response. Other viruses, such as rhinovirus and coronavirus, can cause irritation of pharyngeal mucosa secondary to nasal secretions. [3]

Streptococcal infections are characterized by local invasion and release of extracellular toxins and proteases. In addition, M protein fragments of certain serotypes of GAS are similar to myocardial sarcolemma antigens and are linked to rheumatic fever and subsequent heart valve damage. The prevalence rates of these serotypes of GAS have been becoming rarer over the past several years. Acute glomerulonephritis may result from antibody-antigen complex deposition in glomeruli. [4]

Frequency

United States

Children experience more than 5 upper respiratory infections (URIs) per year and an average of one streptococcal infection every 4 years. The occurrence in adults is about one half that rate. The most significant bacterial agent causing pharyngitis in both adults and children is GAS infection (Streptococcus pyogenes), and the most common viruses are rhinovirus and adenovirus. GAS is most prevalent in late fall through early spring. [2]

International

The incidence of pharyngitis is higher internationally. Antibiotic resistance may be more prevalent in some countries because of overprescription of antibiotics. Note, however, that despite this, there has never been a documented case of GAS resistant to penicillin anywhere in the world. [5]

A study by Banigo et al reported that the reduction in the number of tonsillectomies performed in England (28,309 in 1990/1991 vs 6327 in 2013/2014) correlates with an increase in the number of hospital admissions in that country for acute tonsillitis and pharyngitis and with an increase in invasive group A beta-hemolytic streptococcal (GABHS) infections. Indeed, over the course of the 1990/1991 to 2013/2014 period, the number of invasive GABHS infections rose more than two-fold in children aged 14 years or younger. [6]

Mortality/Morbidity

In the developing world, an estimated 20 million people are affected by acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease, making this the leading cause of cardiac death during the first 5 decades of life. This incidence of rheumatic heart disease is dramatically lower in most developed countries, but localized outbreaks have occurred in the Western world. Despite this, new cases of rheumatic heart disease in the United States are extremely rare. [7] The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) stopped tracking the incidence of rheumatic heart disease in the United States in 1994, when the incidence dropped to less than 1 case per million US general population. [8]

Other sequelae of streptococcal pharyngitis include acute glomerulonephritis, peritonsillar abscess, and toxic shock syndrome.

Mortality from pharyngitis is rare but may result from one of its complications, most notably airway obstruction.

Age

Pharyngitis occurs with much greater frequency in the pediatric population. Approximately 15-30% of sore throats in children are caused by group A beta-hemolytic streptococcal (GABHS) infections, compared with 5-15% of adults. [2, 9]

The peak incidence of bacterial and viral pharyngitis occurs in the school-aged child aged 4-7 years, with GABHS occurring primarily in patients aged 5-15 years. Pharyngitis, especially GAS infection, is rare in children younger than 3 years.

In a study of 3098 pediatric patients with pharyngitis, Nishiyama et al found the prevalence of GAS pharyngitis to be 1.2% in patients below age 1 year and 3.9% in patients aged 1 year. [10]

-

Streptococcus pyogenes at 100X magnification.

-

Rapid antigen detection test for group A beta-hemolytic streptococci.

-

Posterior pharynx with petechiae and exudates in a 12-year-old girl. Both the rapid antigen detection test and throat culture were positive for group A beta-hemolytic streptococci.