Background

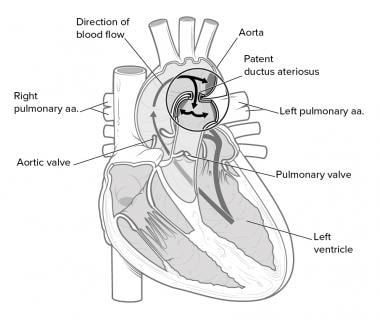

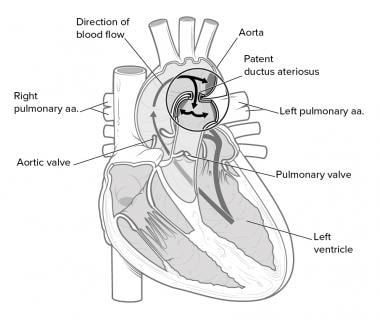

Patent ductus arteriosus (PDA), in which there is a persistent communication between the descending thoracic aorta and the pulmonary artery that results from failure of normal physiologic closure of the fetal ductus (see image below), is one of the more common congenital heart defects.

Schematic diagram of a left-to-right shunt of blood flow from the descending aorta via the patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) to the main pulmonary artery.

Schematic diagram of a left-to-right shunt of blood flow from the descending aorta via the patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) to the main pulmonary artery.

The patient presentation of patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) varies widely. Although frequently diagnosed in infants, the discovery of this condition may be delayed until childhood or even adulthood. In isolated patent ductus arteriosus (PDA), signs and symptoms are consistent with left-to-right shunting. The shunt volume is determined by the size of the open communication and the pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR).

Patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) may also exist with other cardiac anomalies, which must be considered at the time of diagnosis. In many cases, the diagnosis and treatment of a patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) is critical for survival in neonates with severe obstructive lesions to either the right or left side of the heart.

Historical information

Galen initially described the ductus arteriosus in the early first century. Harvey undertook further physiologic study in fetal circulation. However, it was not until 1888 that Munro conducted the dissection and ligation of the ductus arteriosus in an infant cadaver, and it would be another 50 years before Robert E. Gross successfully ligated a patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) in a 7-year-old child. [1] This was a landmark event in the history of surgery and heralded the true beginning of the field of congenital heart surgery. Catheter-based closure of the structure was first performed in 1971.

See also Patent Ductus Arteriosus Surgery and Eisenmenger Syndrome.

Anatomy

During fetal life, the ductus arteriosus is a normal structure that allows most of the blood leaving the right ventricle to bypass the pulmonary circulation and pass into the descending aorta. Typically, only about 10% of the right ventricular output passes through the pulmonary vascular bed.

The ductus arteriosus is a remnant of the distal sixth aortic arch and connects the pulmonary artery at the junction of the main pulmonary artery and the origin of the left pulmonary artery to the proximal descending aorta just after the origin of the left subclavian artery. It passes from the anterior aspect of the pulmonary artery to the posterior aspect of the aorta. Typically, the ductus has a conical shape with a large aortic end tapering into the small pulmonary connection. The ductus may take many shapes and forms, from short and tubular to long and tortuous.

An anatomic marker of the ductus is the recurrent laryngeal nerve, which nerve typically arises from the vagus nerve just anterior and caudal to the ductus and loops posteriorly around the ductus to ascend behind the aorta en route to the larynx. It is the most commonly injured anatomic structure in ductal ligation. Other less commonly injured structures include the phrenic nerve and the thoracic duct.

Most typically, the patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) is a left aortic remnant; however, it can be right-sided or on both the left side and right side. Although a left ductus arteriosus is a normal structure during normal fetal development, the presence of a right ductus arteriosus is usually associated with other congenital abnormalities of the cardiovascular system, most typically involving the aortic arch or conotruncal development.

The Krichenko classification of PDA is based on angiography and includes type A (conical), type B (window), type C (tubular), type D (complex), and type E (elongated) PDA.

In the presence of complex congenital heart defects, the usual anatomy of the ductus may not be present. Anatomic abnormalities can vary widely and are common in conjunction with complex aortic arch anomalies. Structures that have been mistaken for the patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) in surgical procedures include the aorta, the pulmonary artery, and the carotid artery.

Pathophysiology

The ductus arteriosus is normally patent during fetal life; it is an important structure in fetal development as it contributes to the flow of blood to the rest of the fetal organs and structure. From the 6th week of fetal life onwards, the ductus is responsible for most of the right ventricular outflow, and it contributes to 60% of the total cardiac output throughout the fetal life. Only about 5-10% of its outflow passes through the lungs.

This patency is promoted by continual production of prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) by the ductus. Closure of the ductus before birth may lead to right heart failure. Prostaglandin antagonism, such as maternal use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications (NSAIDs), can cause fetal closure of the ductus arteriosus.

Thus, a patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) produces a left-to-right shunt. In other words, it allows blood to go from the systemic circulation to the pulmonary circulation. Therefore, pulmonary blood flow is excessive (see the image below). Pulmonary engorgement results with decreased pulmonary compliance. The reaction of the pulmonary vasculature to the increased blood flow is unpredictable.

Schematic diagram of a left-to-right shunt of blood flow from the descending aorta via the patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) to the main pulmonary artery.

Schematic diagram of a left-to-right shunt of blood flow from the descending aorta via the patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) to the main pulmonary artery.

The magnitude of the excess pulmonary blood flow depends on relatively few factors. The larger the internal diameter of the most narrow portion of the ductus arteriosus, the larger the left-to-right shunt. If the ductus arteriosus is restrictive, then the length of the narrowed area also affects the magnitude of the shunt. A longer ductus is associated with a smaller shunt. Finally, the magnitude of the left-to-right shunt is partially controlled by the relationship of the pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) to the systemic vascular resistance (SVR).

If the SVR is high and/or the PVR is low, the flow through the ductus arteriosus is potentially large. Beginning at the ductus arteriosus, the course of blood flow (through systole and diastole) in a typical patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) with pulmonary overcirculation is as follows: patent ductus arteriosus (PDA), pulmonary arteries, pulmonary capillaries, pulmonary veins, left atrium, left ventricle, aorta, patent ductus arteriosus (PDA). Therefore, a large left-to-right shunt through a patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) results in left atrial and left ventricular enlargement. The pulmonary veins and the ascending aorta can also be dilated with a sufficiently large patent ductus arteriosus (PDA). In addition, if little or no restriction is present at the level of the patent ductus arteriosus (PDA), pulmonary hypertension results.

Functional and anatomic closure

In the fetus, the oxygen tension is relatively low, because the pulmonary system is nonfunctional. Coupled with high levels of circulating prostaglandins, this acts to keep the ductus open. The high levels of prostaglandins result from the little amount of pulmonary circulation and the high levels of production in the placenta.

At birth, the placenta is removed, eliminating a major source of prostaglandin production, and the lungs expand, activating the organ in which most prostaglandins are metabolized. In addition, with the onset of normal respiration, oxygen tension in the blood markedly increases. Pulmonary vascular resistance decreases with this activity.

Normally, functional closure of the ductus arteriosus occurs by about 15 hours of life in healthy infants born at term. This occurs by abrupt contraction of the muscular wall of the ductus arteriosus, which is associated with increases in the partial pressure of oxygen (PO2) coincident with the first breath. A preferential shift of blood flow occurs; the blood moves away from the ductus and directly from the right ventricle into the lungs. Until functional closure is complete and PVR is lower than SVR, some residual left-to-right flow occurs from the aorta through the ductus and into the pulmonary arteries.

This was first demonstrated by multiple experiments in the 1940s and has been subsequently confirmed. Although the neonatal ductus appears to be highly sensitive to changes in arterial oxygen tension, the actual reasons for closure or persistent patency are complex and involve manipulation by the autonomic nervous system, chemical mediators, and the ductal musculature.

A balance of factors that cause relaxation and contraction determine the vascular tone of the ductus. Major factors causing relaxation are the high prostaglandin levels, hypoxemia, and nitric oxide production in the ductus. Factors resulting in contraction include decreased prostaglandin levels, increased PO2, increased endothelin-1, norepinephrine, acetylcholine, bradykinin, and decreased PGE receptors. Increased prostaglandin sensitivity, in conjunction with pulmonary immaturity leading to hypoxia, contributes to the increased frequency of patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) in premature neonates.

Although functional closure usually occurs in the first few hours of life, true anatomic closure, in which the ductus loses the ability to reopen, may take several weeks. A second stage of closure related to fibrous proliferation of the intima is complete in 2-3 weeks.

Cassels et al defined true persistence of the ductus arteriosus as a patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) present in infants older than 3 months. [2] Thus, patency after 3 months is considered abnormal, and treatment should be considered at this juncture, although urgency is seldom necessary. Some canine breeds, such as certain strains of poodle, have a large prevalence of patent ductus arteriosus (PDA).

Spontaneous closure after 5 months is rare in the full-term infant. Left untreated, patients with a large patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) are at risk to develop Eisenmenger Syndrome, in which the PVR can exceed SVR, and the usual left-to-right shunting reverses to a right-to-left direction. At this stage, the PVR is irreversible, closure of the patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) is contraindicated, and lung transplantation may be the only hope for long-term survival.

Failure of ductus arteriosus to contract

Failure of ductus arteriosus contraction in preterm neonates has been suggested to be due to poor prostaglandin metabolism because of immature lungs. Furthermore, high reactivity to prostaglandin and reduced calcium sensitivity to oxygen in vascular smooth muscle cells contribute to contraction of the ductus. The absence of ductus arteriosus contraction in full-term neonates might be due to failed prostaglandin metabolism most likely caused by hypoxemia, asphyxia, or increased pulmonary blood flow, renal failure, and respiratory disorders.

Cyclooxygenase (COX)-2 (an isoform of COX-producing prostaglandins) induction and expression might also prevent ductal closure. The activation of G protein-coupled receptors EP4 by PGE2, the primary prostaglandin regulating ductal tone leads to ductal smooth muscle relaxation.

During late gestation, the decrease in prostaglandin levels results in constriction of the ductus arteriosus. Thus, the intimal cushions come into contact and occlude the ductus lumen.

Volume-pressure relationships

Further progression of disease is dependent on volume and pressure relationships, as follows:

-

Volume = pressure/resistance

-

High volume yields increasing pulmonary artery pressures, eventually producing endothelial and muscular changes in the vessel wall

-

These changes may eventually lead to pulmonary vascular obstructive disease (PVOD), a condition of resistance to pulmonary blood flow that may be irreversible and will preclude definitive repair

Etiology

Genetics

Familial cases of patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) have been recorded, but a genetic cause has not been determined. In infants born at term who have a persistent patent ductus arteriosus (PDA), the recurrence rate among siblings is 5%. Some early evidence suggests that as many as one third of cases are caused by a recessive trait labeled PDA1, located on chromosome 12, at least in some populations.

Chromosomal abnormalities

Several chromosomal abnormalities are associated with persistent patency of the ductus arteriosus. Implicated teratogens include congenital rubella infection in the first trimester of pregnancy, particularly through 4 weeks' gestation (associated with patent ductus arteriosus [PDA] and pulmonary artery branch stenosis), fetal alcohol syndrome, maternal amphetamine use, and maternal phenytoin use.

Prematurity

Prematurity or immaturity of the infant at the time of delivery contributes to the patency of the ductus. Several factors are involved, including immaturity of the smooth muscle within the structure or the inability of the immature lungs to clear the circulating prostaglandins that remain from gestation. These mechanisms are not fully understood. Conditions that contribute to low oxygen tension in the blood, such as immature lungs, coexisting congenital heart defects, and high altitude, are associated with persistent patency of the ductus.

Other

Other causes include low birth weight (LBW), prostaglandins, high altitude and low atmospheric oxygen tension, and hypoxia.

Epidemiology

The estimated incidence of patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) in US children born at term is between 0.02% and 0.006% of live births. This incidence is increased in children who are born prematurely (20% in premature infants > 32 weeks' gestation up to 60% in those < 28 weeks' gestation), children with a history of perinatal asphyxia, and, possibly, children born at high altitude. In addition, up to 30% of low birth weight infants (< 2500 g) develop a patent ductus arteriosus (PDA). Siblings also have an increased incidence. Perinatal asphyxia usually only delays the closure of the ductus, and, over time, the ductus typically closes without specific therapy.

As an isolated lesion, patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) represents 5-10% of all congenital heart lesions. It occurs in approximately 0.008% of live premature births.

No data support a race predilection. However, there is a female preponderance (female-to-male ratio, 2:1) if the patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) is not associated with other risk factors. In patients in whom the patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) is associated with a specific teratogenic exposure, such as congenital rubella, the incidence is equal between the sexes.

Occasionally, an older child is referred with the late discovery of a typical ductus arteriosus murmur (eg, machinery or continuous murmur).

Prognosis

The prognosis is generally considered excellent in patients in whom the patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) is the only problem. In premature infants who have other sequelae of prematurity, these sequelae tend to dictate prognosis of patent ductus arteriosus (PDA).

Typically, following patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) closure, patients experience no further symptoms and have no further cardiac sequelae. Premature infants who had a significant patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) are more likely to develop bronchopulmonary dysplasia.

Spontaneous closure in those older than 3 months is rare. In those younger than 3 months, spontaneous closure in premature infants is 72-75%. In addition, 28% of children with patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) who were conservatively treated (with prophylactic ibuprofen) reported a 94% closure rate. This rate compared well with rates reported in literature following medical treatment (80-92%).

In the adult patient, the prognosis is more dependent on the condition of the pulmonary vasculature and the status of the myocardium if congestive cardiomyopathy was present before ductal closure. Patients with minimal or reactive pulmonary hypertension and limited myocardial changes may have a normal life expectancy.

Morbidity

Morbidity and mortality rates are directly related to the flow volume through the ductus arteriosus. A large patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) may cause congestive heart failure (CHF); if left untreated for a long period, pulmonary hypertension may develop. Occasionally, the ductus arteriosus patency can be intermittent.

Low birth weight premature infants

As many as 20% of neonates with respiratory distress syndrome have patent ductus arteriosus (PDA). In babies who are less than 1500 g at birth, many studies show the incidence of a patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) to exceed 30%. The increased patency in these groups is thought to be due to both hypoxia in babies with respiratory distress and immature ductal closure mechanisms in premature babies.

Premature babies, particularly low birth weight neonates, are more likely to have problems related to patent ductus arteriosus (PDA). Spontaneous closure of the patent ductus arteriosus (PDA ) in premature neonates is common, but respiratory distress and impaired systemic oxygen delivery (CHF) often drive the need for therapy to effect ductal closure in this group. Low birth weight neonates with a patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) are more likely to develop chronic lung disease.

Mortality

No firm statistics exist, but survival rates are decreased in patients with large shunts. The surgical mortality rate in premature infants ranges from 20% to 41%. With the availability of antibiotics to treat endocarditis and low-risk surgery and catheter techniques to obliterate the patent ductus arteriosus (PDA), the mortality rate appears to be quite low except in the extremely premature infant.

It is estimated that left untreated, the mortality rate for patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) is 20% by age 20 years, 42% by age 45 years, and 60% mortality rate by age 60 years. An estimated 0.6% per year undergoes spontaneous closure.

-

Schematic diagram of a left-to-right shunt of blood flow from the descending aorta via the patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) to the main pulmonary artery.

-

Diagram illustrating the patent ductus arteriosus.

-

Diagram illustrating ligation of the patent ductus arteriosus.

-

Diagram illustrating division and oversewing of the patent ductus arteriosus.

-

Diagram illustrating patch closure of the patent ductus arteriosus.