Background

Mitral regurgitation, in the chronic state, is commonly seen in the emergency department. Acute decompensated mitral regurgitation is less frequently encountered. An understanding of the underlying etiologies and pathophysiology of the condition is critical to direct appropriate treatment.

Acute mitral regurgitation is characterized by an increase in preload and a decrease in afterload causing an increase in end-diastolic volume (EDV) and a decrease in end-systolic volume (ESV). This leads to an increase in total stroke volume (TSV) to supranormal levels. However, forward stroke volume (FSV) is diminished because much of the TSV regurgitates as the regurgitant stroke volume (RSV). This, in turn, results in an increase in left atrial pressure (LAP). According to the Laplace principle, which states that ventricular wall stress is proportional to both ventricular pressure and radius, left ventricular wall stress in the acute phase is markedly decreased since both of these parameters are reduced.

Patients must be educated concerning the warning signs and symptoms (eg, congestive heart failure, chest pain) of mitral regurgitation, and they should be advised to see their physician early in the course of the disorder, before symptoms progress.

For patient education resources, see Heart Health Center, as well as Mitral Valve Prolapse.

Pathophysiology

Mitral regurgitation can be divided into the following three stages: acute, chronic compensated, and chronic decompensated.

Acute mitral regurgitation classically occurs with a spontaneous chordae tendineae or papillary muscle rupture secondary to myocardial infarction. Other causes include rupture of these structures due to mitral valve prolapse, endocarditis, and trauma. In this state, a sudden volume and pressure overload occurs on an unprepared left ventricle and left atrium, with an abrupt increase in left ventricular stroke work. Increased left ventricular filling pressures, combined with the reflux of blood from the left ventricle into the left atrium during systole, results in elevated left atrial pressures. This increased pressure is transmitted to the lungs, resulting in acute pulmonary edema and dyspnea.

If the patient tolerates the acute phase, the chronic compensated phase begins. The chronic compensated phase results in eccentric left ventricular hypertrophy. The combination of increased preload and hypertrophy produces increased end-diastolic volumes, which, over time, result in left ventricular muscle dysfunction. This muscle dysfunction impairs the emptying of the ventricle during systole. Therefore, regurgitant volume and left atrial pressures increase, leading to pulmonary congestion.

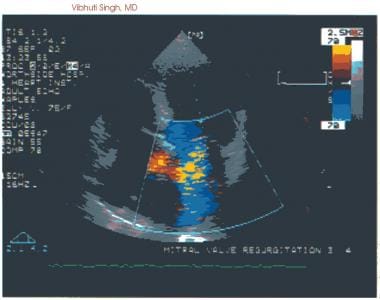

See the image below.

Etiology

Acute rheumatic heart disease remains a significant consideration in those with mitral regurgitation who are younger than 40 years.

Mitral valve prolapse (MVP) (ie, myxomatous degeneration) accounts for approximately 45% of the cases of mitral regurgitation in the Western world. The causative agent is unknown in this condition. Myxomatous degeneration is usually a slow process, with a major complication being the rupture of the chordae tendineae. (Acute regurgitation, as mentioned earlier, can be caused by chordae tendineae rupture or papillary muscle dysfunction.) The literature now seems to suggest that MVP has become the most common cause of mitral regurgitation in the adult population.

In addition, MVP and coronary artery disease (CAD) have become major mechanisms for incompetence of the mitral valve. Ischemia is responsible for 3-25% of mitral regurgitation. The severity of regurgitation is directly proportional to the degree of left ventricular hypokinesis.

Mitral annular calcification can contribute to regurgitation. Impaired constriction of the annulus results in poor valve closure.

Left ventricular dilatation and heart failure can produce annular dilatation and poor valve closure resulting in mitral regurgitation.

Tendineae rupture can be due to endocarditis, myocardial infarction, or trauma.

Papillary muscle dysfunction usually is caused by myocardial ischemia or infarction.

Other causes include the following:

Epidemiology

United States data

Previously, chronic rheumatic heart disease was the most common cause of acquired mitral valve disease in the Western world. More recently, however, mitral valve prolapse (MVP) has become the most common cause, responsible for 45% of cases of mitral regurgitation. In the Framingham cohort, using specific echocardiographic criteria, MVP was diagnosed in 2.4% of a representative population of 3,491 subjects, a lower prevalence than had previously been reported. [1]

International data

In the developing world, rheumatic heart disease remains by far the leading cause of mitral regurgitation.

Sex- and age-related demographic

In those younger than 20 years, males are affected more often than females. In those older than 20 years, no sexual predilection exists. Males older than 50 years are affected more severely.

Of cases caused by prior rheumatic disease, the mean patient age is 36 ± 6 years.

Prognosis

The prognosis of patients with mitral regurgitation depends on the underlying etiologies and the state of the left ventricular function. The extent of left ventricular dysfunction from underlying ischemia is the primary prognostic determinant in those with regurgitation secondary to coronary artery disease (CAD).

In a 2020 report of outcomes from 1342 patients from the Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) national database who underwent mitral valve surgery for ischemic papillary muscle rupture, the operative mortality was 20.0%. [2] Predictors of operative mortality included mitral valve replacement, older age, lower albumin levels, the presence of cardiogenic shock, an ejection fraction below 25%, and emergent salvage status. Major morbidities included prolonged ventilation (61.8%), acute renal failure (15.4%), reoperation (10.2%), and stroke (5.2%). [2]

Morbidity/mortality

Consider the following:

-

Acute pulmonary edema and cardiogenic shock often complicate the course of acute mitral regurgitation. The operative mortality in these cases approaches 80%. A patient with ruptured chordae tendineae and minimal symptoms has a much better prognosis.

-

With chronic mitral regurgitation, volume overload is tolerated very well for years before symptoms of failure develop. Left atrial enlargement predisposes patients to the onset of atrial fibrillation, with subsequent complications of embolization. In addition, these patients are susceptible to endocarditis. A study of the survival of patients with chronic regurgitation using randomly selected patients revealed that 80% of the patients were alive 5 years later, and 60% were alive after 10 years.

-

Most patients with mitral valve prolapse are asymptomatic. Prolapse in those older than 60 years is frequently associated with chest pain, arrhythmias, and heart failure. The prognosis of these patients is good; however, sudden death, endocarditis, and progressive regurgitation occur rarely.

-

When ischemic heart disease is the mechanism for regurgitation, the extent of anatomic disease and left ventricular performance are prognostic determinants. Complicating events include sudden death and myocardial infarction.

Patients with acute mitral regurgitation secondary to infarction emergently requiring valve replacement have a 60-80% mortality if they present with severe pulmonary edema.

Complications

Major complications from chronic regurgitation include the following:

-

Severe left ventricular dysfunction

-

Chronic congestive heart failure

-

Atrial fibrillation and its complications (eg, left atrial thrombus with embolization and stroke)

-

Sudden death, ruptured chordae tendineae, and endocarditis remain infrequent complications of regurgitation secondary to long-standing mitral prolapse.

-

Acute mitral regurgitation. Transesophageal echocardiogram demonstrating prolapse of both mitral valve leaflets during systole.

-

Acute mitral regurgitation. Transthoracic echocardiogram demonstrating bioprosthetic mitral valve dehiscence with paravalvular regurgitation.

-

Acute mitral regurgitation. Severe mitral regurgitation as depicted with color Doppler echocardiography.

-

Acute mitral regurgitation. Four-chamber apical view of a two-dimensional transthoracic echocardiogram demonstrates mitral valve prolapse (MVP), a common cause of mitral regurgitation.