Practice Essentials

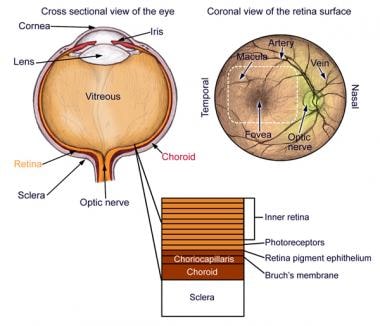

Uveitis is defined as inflammation of the uveal tract, which is further subdivided into anterior and posterior components. The anterior tract is composed of the iris and ciliary body, whereas the posterior tract includes choroid. Hence, uveitis is inflammation of any of these components and also may include other surrounding tissues such as sclera, retina, and optic nerve. [1] Uveitis often is idiopathic but may be triggered by genetic, traumatic, immune, or infectious mechanisms.

Signs and symptoms

Symptoms of uveitis depend on several variables, the most important of which are type (ie, anterior, posterior, intermediate) and duration of symptoms (ie, acute, chronic). Furthermore, a thorough review of systems (eg, shortness of breath, arthritis, rash, trauma, back pain, travel history, etc) should be conducted to elucidate potential underlying etiologies.

Acute anterior uveitis presents as follows:

-

Pain, generally developing over a few hours or days except in cases of trauma

-

Redness

-

Photophobia

-

Blurred vision

-

Increased lacrimation

Chronic anterior uveitis presents primarily as blurred vision and mild redness. Patients have little pain or photophobia except when having an acute episode.

Posterior uveitis presents as follows [2] :

-

Blurred vision and floaters

-

Absence of symptoms of anterior uveitis (ie, pain, redness, and photophobia)

The presence of symptoms of posterior uveitis, redness and pain suggests one of the following:

-

Anterior chamber involvement

-

Bacterial endophthalmitis

-

Posterior scleritis

Intermediate uveitis presents as follows [2] :

-

Painless floaters and decreased vision (similar to posterior uveitis)

-

Minimal photophobia or external inflammation

Patients with panuveitis may present with any or all of the above symptoms.

Physical examination findings are as follows:

-

Lids, lashes, and lacrimal ducts are normal.

-

Conjunctival examination reveals 360° perilimbal injection, which increases in intensity as it approaches the limbus; this is the reverse of the pattern seen in conjunctivitis, in which the most severe inflammation occurs at a distance from the limbus. [3]

-

Visual acuity may be decreased in the affected eye.

-

Extraocular movement is generally normal.

-

Pupillary examination may reveal direct photophobia when the light is directed into the affected eye, as well as consensual photophobia when light is directed into the uninvolved eye; consensual photophobia is typical of iritis, whereas photophobia due to more superficial causes, such as conjunctivitis, is direct but not consensual.

-

Pupillary miosis is common.

Slit-lamp examination

-

This is the most important aspect of the examination.

-

Examine the cornea via direct illumination with a broad beam at a 30°-40° angle between the viewing microscope and the light source.

-

Examine the epithelium for abrasions, edema, ulcers, or foreign bodies.

-

Inspect the stroma for deep ulcers and edema.

-

Keratitic precipitates (white blood cells) on the endothelium are a hallmark of iritis.

-

Ciliary flush, a violaceous ring around the cornea, is highly indicative of intraocular inflammation. [1]

-

Corneal edema and vitreous haze (large collection of inflammatory cells in the vitreous) may be observed.

-

Intraocular pressure may be normal or slightly decreased in the acute phase owing to decreased aqueous humor production; however, pressure may become elevated as the inflammation subsides.

-

Opacities of the lens (cataracts) may be present but are not specific for uveitis.

The most important structure to examine is the anterior chamber, as follows:

-

Examine the anterior chamber using a vertically and horizontally short beam.

-

Normally, the aqueous humor in the anterior chamber is optically clear.

-

In uveitis, an increase in the protein content of the aqueous causes an effect upon examination known as flare, which is similar to that produced by a moving projector beam in a dark smoky room.

-

White or red blood cells may be observed; layering of white blood cells in the anterior chamber is called hypopyon.

Grading of blood cells in the anterior chamber is as follows:

-

0 - None

-

1+ - Faint (barely detectable)

-

2+ - Moderate (clear iris and lens details)

-

3+ - Moderate (hazy iris and lens details)

-

4+ - Intense (fibrin deposits, coagulated aqueous)

See Clinical Presentation for more detail.

Diagnosis

Laboratory studies are unlikely to be helpful in cases of mild, unilateral nongranulomatous uveitis in the following settings:

-

Trauma

-

Known systemic disease

-

History and physical not suggestive of systemic disease

A nonspecific workup is indicated if the history and the physical examination findings are unremarkable in the presence of uveitis that is bilateral, granulomatous, or recurrent. [1, 2] The following tests may be ordered by the consulting ophthalmologist, to be followed and further coordinated by the primary care physician:

-

Complete blood cell (CBC) count

-

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR)

-

Antinuclear antibody (ANA)

-

Rapid plasma reagin (RPR)

-

Venereal disease research laboratory (VDRL)

-

Purified protein derivative (PPD)/Qantiferon

-

Lyme titer

-

HLA testing for ankylosing spondylarthroses

-

Chest radiography (to assess for sarcoidosis or tuberculosis)

-

Urinalysis (for red blood cells or casts)

-

Infectious workup (eg, HIV, HSV, CMV, toxoplasmosis), depending on the presentation

See Workup for more detail.

Management

Uveitis has no standard treatment regimen. Usually, the initial course of management is a stepwise approach starting with cycloplegics and corticosteroid drops to control pain and reduce inflammation. Progression to immunosuppressive agents may be necessary after consideration of the baseline etiology; however, this progression would be initiated by a primary care physician in consultation with an ophthalmologist after including physician and patient factors, which are beyond the scope of this review. Topical corticosteroid eye drops or sustained-release implants are traditionally used as treatment modalities. Newer administration routes (eg, intravitreal injection, suprachoroidal injection) have been approved by the FDA. There is growing evidence for the use of anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha agents, such as adalimumab (Humira), which has also been FDA approved for treatment of uevitis. [4, 5, 6]

Considerations prior to initiating treatment include the following:

-

Supporting evidence is sparse

-

Check intraocular pressure and rule out herpes simplex virus (HSV) keratitis before starting topical corticosteroids

-

Initiate steroid treatment only in consultation with an ophthalmologist

See Treatment and Medication for more detail.

Background

Uveitis is defined as inflammation of the uveal tract, the anatomy of which includes the iris, ciliary body, and choroid.

The iris regulates the amount of light that enters the eye, the ciliary body produces aqueous humor and supports the lens, and the choroid provides oxygen and nourishment for the retina.

A classification scheme for uveitis exists based upon anatomic location. [7]

Table 1. Classification of Uveitis (Open Table in a new window)

Type |

Primary Site of Inflammation |

Manifestation |

Anterior uveitis |

Anterior chamber |

Iritis/iridocyclitis/anterior cyclitis |

Intermediate uveitis |

Vitreous |

Vitreitis/hyalitis/pars planitis |

Posterior uveitis |

Choroid |

Choroiditis/chorioretinitis/retinochoroiditis/retinitis/neuroretinitis |

Panuveitis |

Anterior chamber, vitreous, and/or choroid |

All of the above |

Uveitis, particularly posterior uveitis, is a common cause of preventable blindness, so it is deemed a sight-threatening condition. Anterior uveitis is the form most likely to present to the emergency department. When the inflammation is limited to the iris, it is termed iritis. If the ciliary body is also involved, it is called iridocyclitis.

After anatomic classification, uveitis is further described by the following [8] :

-

Onset (sudden vs insidious)

-

Duration (limited, < 3 months in duration; persistent, >3 months in duration)

-

Course (acute, recurrent, or chronic)

-

Laterality (unilateral vs bilateral)

The distribution of general uveitis cases by anatomic site of disease has been found to differ significantly between community-based practice (anterior, 90.6%; intermediate, 1.4%; posterior 4.7%; panuveitis, 1.4%) and university referral practice (anterior, 60.6%; intermediate, 12.2%; posterior, 14.6%; panuveitis, 9.4%; P< 0.00005). [9]

Pathophysiology

The etiology of uveitis varies between populations and is often idiopathic [8] ; however, genetic, traumatic, or infectious mechanisms are known to promote or trigger uveitis. Diseases that predispose a patient to uveitis and are likely to present to the emergency department include inflammatory bowel disease, rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), sarcoidosis, tuberculosis, syphilis, and AIDS.

The mechanism for trauma is believed to be a combination of microbial contamination and accumulation of necrotic products at the site of injury, stimulating the body to mount an inflammatory response in the anterior segment of the eye. [8, 10]

For infectious etiologies of uveitis, it is postulated that the immune reaction directed against foreign molecules or antigens may injure the uveal tract vessels and cells.

When uveitis is found in association with autoimmune disorders, the mechanism may be a hypersensitivity reaction involving immune complex deposition within the uveal tract.

In one study at a tertiary referral center by Rodriguez et al, [11] the distribution in etiology among all anatomic forms of uveitis, anterior, intermediate, and posterior, were as follows:

-

Idiopathic (34%)

-

Seronegative spondyloarthropathies (10.4%)

-

Sarcoidosis (9.6%)

-

Juvenile rheumatoid arthritis (JRA) (5.6%)

-

SLE (4.8%)

-

Behçet disease (2.5%)

-

AIDS (2.4%)

Seronegative arthropathies include nonspecific, ankylosing spondylitis, Reiter syndrome, psoriatic arthropathy, and inflammatory bowel disease.

In the same Rodriguez et al study, [11] anterior uveitis was the most common form at 51.6%, and the etiologic distribution was as follows:

-

Idiopathic (37.8%)

-

Seronegative arthropathies (21.6%)

-

JRA (10.8%)

-

Herpes virus (9.7%)

-

Sarcoidosis (5.8%)

-

SLE (3.3%)

-

Rheumatoid arthritis (0.9%)

Posterior uveitis was next most common, with 19.4% of cases, the most common etiologies being Toxoplasma (24.6%), idiopathic (13.3%), cytomegalovirus (CMV) (11.6%), SLE (7.9%), and sarcoidosis (7.5%).

A more rare cause of uveitis are medications. Few studies and case reports have associated bisphosphonates, fluoroquinolones, hormone replacement therapy, and etanercept with the development of uveitis. [12]

Frequency

United States

The approximate estimated annual incidence of uveitis in the United States ranges from 25-52 cases per 100,000 persons per year. [4, 13, 14] A 2021 systemic review found the estimated prevalence of non-infectious uveitis to be 121 per 100,000. [12]

International

The incidence and prevalence of uveitis vary widely internationally. Finland has one of the highest annual incidences of uveitis, probably because of the high frequency of HLA-B27 spondyloarthropathy among the population. [4] The reported prevalence of uveitis (infectious and non-infectious) in China ranged from 152 per 100,000 in China; 173 per 100,000 in South Korea; 194 per 100,000 persons in Taiwan; and 317-730 per 100,000 in India. [12]

Race

Racial predisposition to uveitis is related to the patient's underlying systemic disease, as follows [2] :

-

Whites: HLA-B27, multiple sclerosis

-

Blacks: Sarcoidosis, SLE

-

Mediterranean/Middle Eastern descent: Behçet disease

-

Asians: Behçet disease

Sex

In general, uveitis has no sexual predisposition except in cases secondary to autoimmune diseases, which are more common in women compared to men. [2, 12]

Age

Most people who develop uveitis are aged 20 to 50 years.

Mortality/Morbidity

No deaths due to iritis or uveitis have been reported.

Uveitis has been reported to be responsible for 5-20% of total blindness in Europe and North America and up to 25% of blindness in the developing world. [15, 12]

Morbidity results from posterior synechiae formation (adhesions between the iris and the lens) that may lead to high intraocular pressure, optic nerve loss and visual impairments. Blindness may result from inadequate treatment. Complications of medications, specifically topical steroids, may include glaucoma, cataracts, and potential vision deterioration. [1, 16]

Prognosis

Generally, the prognosis for iritis and uveitis is good with appropriate treatment. However, uveitis can be recurrent and affect the contralateral eye, especially with underlying inflammatory diseases.

Patient Education

For patient education resources, see the Eye and Vision Center. Also, see the patient education articles Anatomy of the Eye and Iritis.

-

Anatomy of the eye.

-

Small stellate keratic precipitates with fine filaments in a patient with Fuchs heterochromic iridocyclitis.