Practice Essentials

Herpes simplex encephalitis (HSE) is an acute or subacute illness that causes both general and focal signs of cerebral dysfunction. Brain infection is thought to occur by means of direct neuronal transmission of the virus from a peripheral site to the brain via the trigeminal or olfactory nerve and indirect immune-mediated processes inducing neuroinflammation. The exact pathogenesis is unclear, and factors that precipitate HSE are unknown. See the image below.

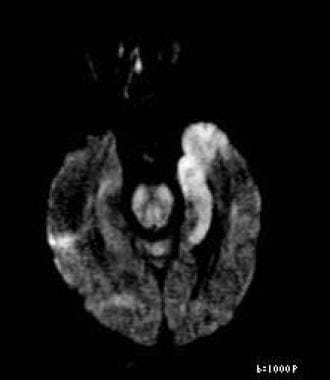

Axial diffusion-weighted image reveals restricted diffusion in left medial temporal lobe consistent with herpes encephalitis. This patient also had positive result on polymerase chain reaction assay for herpes simplex virus, which is both sensitive and specific. In addition, patient had periodic lateralized epileptiform discharges on electroencephalography, which supports diagnosis of herpes encephalitis.

Axial diffusion-weighted image reveals restricted diffusion in left medial temporal lobe consistent with herpes encephalitis. This patient also had positive result on polymerase chain reaction assay for herpes simplex virus, which is both sensitive and specific. In addition, patient had periodic lateralized epileptiform discharges on electroencephalography, which supports diagnosis of herpes encephalitis.

See Herpes Simplex Viruses: Test Your Knowledge, a Critical Images slideshow, for more information on clinical, histologic, and radiographic imaging findings in HSV-1 and HSV-2.

Signs and symptoms

Patients with HSE may have a prodrome of malaise, fever, headache, and nausea, followed by acute or subacute onset of an encephalopathy whose symptoms include lethargy, confusion, and delirium. However, no pathognomonic clinical findings reliably distinguish HSE from other neurologic disorders with similar presentations. [4]

The following are typically the most common symptoms of HSE [5] :

-

Fever (90%)

-

Headache (81%)

-

Psychiatric symptoms (71%)

-

Seizures (67%)

-

Vomiting (46%)

-

Focal weakness (33%)

-

Memory loss (24%)

The initial presentation may be mild or atypical in immunocompromised patients (eg, those with HIV infection or those receiving steroid therapy). [6]

See Clinical Presentation for more detail.

Diagnosis

There are no pathognomonic clinical findings associated with HSE. Focal neurologic deficits, CSF pleocytosis, and abnormalities on CT scanning may be absent initially. Therefore, a high index of suspicion is required to make the diagnosis, particularly in immunocompromised patients with febrile encephalopathy. Expeditious evaluation is indicated after the diagnosis of HSE is considered.

HSE occurs as 2 distinct entities:

-

In children older than 3 months and in adults, HSE is usually localized to the temporal and frontal lobes and is caused by HSV-1

-

In neonates, however, brain involvement is generalized, and the usual cause is HSV-2, which is acquired at the time of delivery

Typical findings on presentation include the following [5] :

-

Alteration of consciousness (97%)

-

Fever (92%)

-

Dysphasia (76%)

-

Ataxia (40%)

-

Seizures (38%): Focal (28%); generalized (10%)

-

Hemiparesis (38%)

-

Cranial nerve defects (32%)

-

Visual field loss (14%)

-

Papilledema (14%)

Meningeal signs may be present, but meningismus is uncommon. Unusual presentations also occur. Both HSV-1 and HSV-2 may produce a more subacute encephalitis, apparent psychiatric syndromes, and benign recurrent meningitis. Less commonly, HSV-1 may produce a brainstem encephalitis, and HSV-2 may produce a myelitis.

Lab tests

Routine laboratory tests are generally not helpful in the diagnosis of HSE but may show evidence of infection or detect renal disease. The diagnosis can be confirmed only by means of PCR or brain biopsy.

Studies that may be helpful in patients with suspected HSE include the following:

-

Serologic analysis of blood or CSF: Retrospective diagnosis only; not for acute diagnosis and management

-

Tzanck preparations of vesicular lesions: For confirmation of HSV in neonates with HSE

-

Quantification of intrathecal antibodies: For evidence of CNS antibody response

Imaging tests

The following are imaging studies used in the evaluation of suspected HSE:

-

MRI of the brain: The preferred imaging study

-

CT scanning of the brain: Less sensitive than MRI

-

EEG: Low specificity (32%) but 84% sensitivity to abnormal patterns in HSE (eg, continous periodic lateralized epileptiform discharges, intermittent delta- and theta-slowing)

Procedures

-

Lumbar puncture for CSF analysis

-

Brain biopsy: Diminishing role; rarely used in current practice for either confirming diagnosis of HSE or establishing alternative diagnoses

Viral CSF cultures are rarely positive and should not be relied on to confirm the diagnosis. However, HSV can be cultured from the CSF in about one third of affected neonates.

See Workup for more detail.

Management

HSE is primarily managed with antiviral therapy in the form of IV acyclovir. Start empiric IV acyclovir therapy promptly in patients with suspected HSE pending confirmation of the diagnosis, because acyclovir is relatively nontoxic and because the prognosis for untreated HSE is poor.

Pharmacotherapy

Medications used in the management of HSE include the following:

-

Antivirals (eg, acyclovir, famciclovir): Drug of choice for HSE; to shorten the clinical course, prevent complications, prevent development of latency and subsequent recurrences, decrease transmission, and eliminate established latency

-

Anticonvulsants (eg, carbamazepine, phenytoin): To terminate clinical and electrical seizure activity as rapidly as possible and to prevent seizure recurrence

-

Diuretics (eg, furosemide, mannitol): To manage increased intracranial pressure in complications resulting from HSE

Nonpharmacotherapy

Supportive care in patients with HSE includes the following:

-

Airway, breathing, circulatory support

-

Nutritional and fluid support

-

Universal precautions

-

Monitoring for increase intracranial pressure and seizures

-

Admission to ICU as needed

See Treatment and Medication for more detail.

Background

Despite advances in antiviral therapy over the past 2 decades, herpes simplex encephalitis (HSE) remains a serious illness with significant risks of morbidity and death. [1, 2, 3] Herpes simplex encephalitis occurs as 2 distinct entities:

-

In children older than 3 months and in adults, HSE is usually localized to the temporal and frontal lobes and is caused by herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1).

-

In neonates, however, brain involvement is generalized, and the usual cause is herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2), which is acquired at the time of delivery.

Except where otherwise specified, this article describes HSE as it occurs in older children and adults (as opposed to neonatal HSE). HSE must be distinguished from herpes simplex meningitis, which is more commonly caused by HSV-2 than by HSV-1 and which often occurs in association with a concurrent herpetic genital infection. Like other forms of viral meningitis, herpes simplex meningitis usually has a benign course and is not discussed in this article.

Patients with HSV may require long-term antiviral treatment if they have recurrent lesions or if other organ systems are involved (as in herpes simplex keratitis). HSV remains dormant in the nervous system; rarely, it presents as encephalitis, possibly by direct transmission through peripheral nerves to the central nervous system (CNS). This encephalitis is a neurologic emergency and the most important neurologic sequela of HSV.

See the following for more information:

Pathophysiology

The pathogenesis of HSE in humans is poorly understood. Neurons are quickly overwhelmed by a lytic and hemorrhagic process distributed in an asymmetric fashion throughout the medial temporal and inferior frontal lobes. Wasay et al reported temporal lobe involvement in 60% of patients. [9] Fifty-five percent of patients demonstrated temporal and extratemporal pathology, and 15% of patients demonstrated extratemporal pathology exclusively. Involvement of the basal ganglia, cerebellum, and brainstem is uncommon.

The exact mechanism of cellular damage is unclear, but it may involve both direct virus-mediated and indirect immune-mediated processes. The ability of HSV-1 to induce apoptosis (programmed cell death, or “cellular suicide”) in neuronal cells, a property not shared by HSV-2, might explain why the former causes virtually all cases of herpes simplex encephalitis in immunocompetent older children and adults. [10, 11]

A vivid description of the temporal course of tissue destruction is given in an immunohistologic autopsy study of patients succumbing to HSE over periods of days to weeks in the era prior to acyclovir: The impression is of a rapidly spreading wave of viral infection within limbic structures, probably starting on one side of the brain and spreading within it and to the other side, lasting about 3 weeks and resulting in severe necrosis and inflammation in infected parts of the brain. [12]

Brain infection is thought to occur by means of direct neuronal transmission of the virus from a peripheral site to the brain via the trigeminal or olfactory nerve. Factors that precipitate HSE are unknown. The prevalence of HSE is not increased in immunocompromised hosts, but the presentation may be subacute or atypical in these patients. HSV-2 may cause HSE in patients with HIV-AIDS. [13, 14, 15]

HSE represents a primary HSV infection in about one third of cases; the remaining cases occur in patients with serologic evidence of preexisting HSV infection and are due to reactivation of a latent peripheral infection in the olfactory bulb or trigeminal ganglion or to reactivation of a latent infection in the brain itself. A substantial number of neurologically asymptomatic individuals may have latent HSV in the brain. In a postmortem study, HSV was present in the brains of 35% of patients with no evidence of neurologic disease at the time of death. [16]

Neonatal HSE may occur as an isolated CNS infection or as part of disseminated multiorgan disease.

Etiology

As noted (see Pathophysiology), HSE is caused by HSV, an enveloped, double-stranded DNA virus. HSV-1 and HSV-2 are both members of the larger human herpesvirus (HHV) family, which also includes varicella-zoster virus (VZV, or HHV-3) and cytomegalovirus (CMV, or HHV-5). HSV-1, or HHV-1, is the more common cause of adult encephalitis; it is responsible for virtually all cases in persons older than 3 months. HSV-2, or HHV-2, is responsible for a small number of cases, particularly in immunocompromised hosts.

HSV-1 causes oral lesions (so-called fever blisters); these are common and may respond to antiviral medications, though they spontaneously remit in most cases. HSV-2 causes genital lesions. It was previously thought to appear within 1-2 weeks of primary infection, then to recur with lessening severity. That lesions may appear clinically at any interval after primary infection is now known. HSV-2 may be treated with antiviral medications.

In adults, the host immune response, combined with viral factors, determines invasiveness and virulence. Mitchell et al showed that the invasiveness of HSV-1 glycoprotein variants is controlled by the host response. [17] Geiger et al used interferon-gamma–knockout mice to show how interferon-gamma protected against HSV-1–mediated neuronal death. [18] These data suggested that the presentation and severity of encephalitis vary. Recent research suggests that an inborn error of interferon-mediated immunity may predispose the HSV-1 infected individual to developing HSE. [19] Further support comes from additional research suggesting that specific interferon-beta production signaling pathways are important for the control of HSV replication in the brain. [20]

Evidence from a European study suggested that socioeconomic status and geography might affect levels of virus seropositivity. However, clinical correlation is difficult, because HSE can occur at any time, regardless of the patient’s socioeconomic status, age, race, or sex.

In children, encephalitis often results from primary infection with HSV. Approximately 80% of children with HSE do not have a history of labial herpes. Perez de Diego, et al., note inborn errors or novel proteins may play a role in childhood susceptibility to HSE.

Cathomas et al report a case of HSE as a complication of chemotherapy for breast cancer. [21]

Neonatal herpes simplex encephalitis

The predominant pathogen is HSV-2 (75% of cases), which is usually acquired by maternal shedding (frequently asymptomatic) during delivery. A preexisting but recurrent maternal genital herpes infection results in 8% risk of symptomatic infection, usually transmitted at the second stage of labor via direct contact. Should the mother acquire genital herpes during pregnancy, the risk increases to 40%.

The absence of a maternal history of prior genital herpes does not exclude risk; in 80% of cases of neonatal HSE, no maternal history of prior HSV infection is present. Prolonged rupture of the membranes (>6 h) and intrauterine monitoring (eg, attachment of scalp electrodes) are risk factors.

In about 10% of cases, HSV (often type 1) is acquired post partum by contact with an individual who is shedding HSV from a fever blister, finger infection, or other cutaneous lesion. [22, 23]

Epidemiology

In the United States, HSE is the most common nonepidemic encephalitis and the most common cause of sporadic lethal encephalitis. Incidence is 2 cases per million population per year. HSE may occur year-round. HSV-1 is ubiquitous, and HSV-2 is also common. International incidence is similar to that in the United States.

Age-, sex-, and race-related demographics

HSE has a bimodal distribution by age, with the first peak occurring in those younger than 20 years and a second occurring in those older than 50 years. HSE in younger patients usually represents primary infection, whereas HSE in older persons typically reflects reactivation of latent infection. One third of HSE cases occur in children.

Herpes affects both sexes equally, though genital herpes may be more apparent in the male because of anatomy. No racial predilection exists.

Prognosis

Untreated HSE is progressive and often fatal in 7-14 days. A landmark study by Whitley et al in 1977 revealed a 70% mortality in untreated patients and severe neurologic deficits in most of the survivors. [24]

Mortality in patients treated with acyclovir was 19% in the trials that established its superiority to vidarabine. Subsequent trials reported lower mortalities (6-11%), perhaps because they included patients who were diagnosed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) rather than brain biopsy and who thus may have been identified earlier with milder disease. [1, 3]

The mortality of neonatal HSE is substantial, even with treatment; 6% in patients with isolated HSE and 31% in those with disseminated infection.

Sequelae among survivors are significant and depend on the patient’s age and neurologic status at the time of diagnosis. Patients who are comatose at diagnosis have a poor prognosis regardless of their age. In noncomatose patients, the prognosis is age related, with better outcomes occurring in patients younger than 30 years.

Significant morbidity exists among those treated. Neurologic outcomes in survivors treated with acyclovir are as follows:

-

No deficits or mild deficits - 38%

-

Moderate deficits - 9%

-

Severe deficits - 53%

Anterograde memory often is impaired even with successful treatment of HSE. Retrograde memory, executive function, and language ability also may be impaired. A study by Utley et al showed that patients who had a shorter delay (< 5 d) between presentation and treatment had better cognitive outcomes. [25]

Elbers and colleagues followed properly treated children for 12 years after the HSE. They found seizures in 44% of the children and developmental delay in 25% of the children. They concluded that HSE continues to be associated with poor long-term neurologic outcomes despite appropriate therapy. [26]

Shelley and colleagues reported a case of intracerebral hematoma occurring in a patient successfully treated with a full course of acyclovir after apparent eradication of the virus. The hematoma occurred in the region of the encephalitis. [27]

Marschitz and colleagues reported a case of chorea after HSE. [28]

Relapses after HSE have been reported to occur in 5-26% of patients, with most relapses occurring within the first 3 months after completion of treatment. Relapses are more frequent in children than adults. It is unclear whether such relapses represent recurrence of viral infection or an immune-mediated inflammatory process. Some of the relapses reported in earlier studies may have been due to inadequate duration of treatment rather than true recurrences of HSE.

A long-term follow-up study of patients with HSE suggested that the pathogenic mechanisms present during relapses differ from those present during the initial infection. [29] Serial measurements of inflammatory markers as well as HSV viral load in the CSF of relapsing patients demonstrated increased inflammatory markers without detectable HSV during relapses. These findings suggest that immune-mediated events, rather than direct viral-mediated neuronal toxicity, may predominate in relapses.

Patient Education

The belief that HSV-2 lesions appear initially 2 wk after primary infection can lead to false accusations of infidelity. The physician should emphasize that the initial outbreak of lesions may occur at any time after infection, possibly even years later.

Education may help reduce the spread of HSV-2.

For patient education resources, see the Teeth and Mouth Center and the Brain and Nervous System Center, as well as Oral Herpes, Cold Sores, and Encephalitis.

-

Axial proton density-weighted image in 62-year-old woman with confusion and herpes encephalitis shows T2 hyperintensity involving right temporal lobe.

-

Axial gadolinium-enhanced T1-weighted image reveals enhancement of right anterior temporal lobe and parahippocampal gyrus. At right anterior temporal tip is hypointense, crescentic region surrounded by enhancement consistent with small epidural abscess.

-

Axial diffusion-weighted image reveals restricted diffusion in left medial temporal lobe consistent with herpes encephalitis. This patient also had positive result on polymerase chain reaction assay for herpes simplex virus, which is both sensitive and specific. In addition, patient had periodic lateralized epileptiform discharges on electroencephalography, which supports diagnosis of herpes encephalitis.