Practice Essentials

The phylum Echinodermata includes a diverse group of marine animals that are slow moving and nonaggressive, including brittle stars (class Ophiuroidea), starfish (class Asteroidea), sea urchins (class Echinoidea), and sea cucumbers (class Holothuroidea). These animals have pentamerous (5-part) radial symmetry and calcareous skeletons that form thick outer plates and protective spines in some; hence, they are named Echinodermata, which means spiny skin. Injury and envenomation occur almost exclusively from accidental contact or careless handling; bathers, divers, and fishermen are at greatest risk. [1] Poisonous echinoderm ingestions or intoxications are not covered in this article. See the image below.

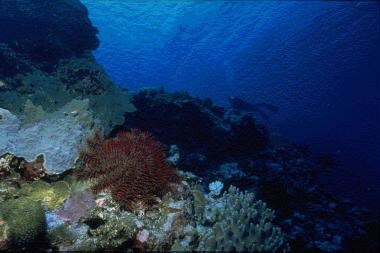

Echinoderm envenomations. Unlike most starfish that are typically pentamerous, the crown-of-thorns starfish (Acanthaster planci) may have as many as 23 arms and a body disc up to 60 cm in diameter. Photo courtesy of Dee Scarr.

Echinoderm envenomations. Unlike most starfish that are typically pentamerous, the crown-of-thorns starfish (Acanthaster planci) may have as many as 23 arms and a body disc up to 60 cm in diameter. Photo courtesy of Dee Scarr.

See Deadly Sea Encounters: Bites and Envenomations, a Critical Images slideshow, to help make an accurate diagnosis.

Presentation

See History and Physical Examination.

Workup

No specific laboratory tests are indicated in the management of echinoderm envenomations; however, in cases of severe systemic symptoms (eg, hypotension, paralysis, respiratory failure), a complete workup to exclude other etiologies may be warranted.

Ocular exposure to holothurin toxins and tentacular fragments following exposure to the organs of Cuvier of sea cucumbers requires a thorough slit lamp examination for retained foreign bodies and evidence of corneal abrasion or keratitis.

Also see Imaging Studies.

Treatment

Medical therapy is directed primarily at local and systemic analgesia, with nonspecific supportive therapy required only in the most severe cases. Prophylactic antibiotics are generally not indicated, except in persons with deep puncture wounds or who are immunocompromised. However, once infection is established, prompt therapy must be instituted with emphasis on coverage for potential marine pathogens. No antivenoms are available. Tetanus prophylaxis is indicated in all marine animal injuries.

Also see Treatment.

Pathophysiology

While most echinoderms are poisonous, and many have sharp spines or spicules capable of causing injury, only a few members of the Asteroidea, Echinoidea, and Holothuroidea classes are capable of causing venomous injuries in humans. In this article, envenomation refers to the parenteral or topical application of toxins produced in specialized glands and tissues with modified application structures (spines, pedicellaria, tentacles). This definition is in contrast to poisoning or intoxication, which refers to the oral ingestion of toxins produced or accumulated in nonspecialized glands or tissues.

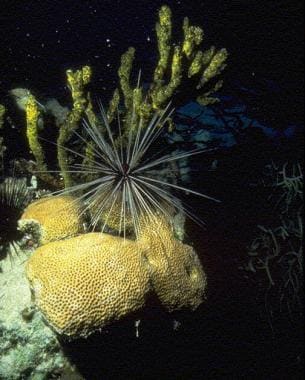

Brittle stars (class Ophiuroidea; see the image below) are not generally considered capable of causing venomous injuries in humans.

Echinoderm envenomations. Close-up of brittle star arm. Although spiny, members belonging to this class (Ophiuroidea) generally are considered harmless. Of the phylum Echinodermata, only starfish (class Asteroidea), sea urchins (class Echinoidea), and sea cucumbers (class Holothuroidea) are capable of envenomation. Photo courtesy of Scott A. Gallagher, MD.

Echinoderm envenomations. Close-up of brittle star arm. Although spiny, members belonging to this class (Ophiuroidea) generally are considered harmless. Of the phylum Echinodermata, only starfish (class Asteroidea), sea urchins (class Echinoidea), and sea cucumbers (class Holothuroidea) are capable of envenomation. Photo courtesy of Scott A. Gallagher, MD.

However, some brittle stars (Ophiomastix annulosa) do possess toxins and are capable of causing paralysis and death in small animals. These animals should be handled with care.

Starfish (Asteroidea) envenomation in humans is well described, with the crown-of-thorns starfish (Acanthaster planci) as the main culprit (see the images below).

Echinoderm envenomations. Detail of the crown-of-thorns starfish (Acanthaster planci) spines, which may grow to 6 cm in length. Photo courtesy of Dee Scarr.

Echinoderm envenomations. Detail of the crown-of-thorns starfish (Acanthaster planci) spines, which may grow to 6 cm in length. Photo courtesy of Dee Scarr.

Echinoderm envenomations. Detail of the crown-of-thorns starfish (Acanthaster planci). Photo courtesy of Scott A. Gallagher, MD.

Echinoderm envenomations. Detail of the crown-of-thorns starfish (Acanthaster planci). Photo courtesy of Scott A. Gallagher, MD.

Acanthaster species possess long (5-6 cm), extremely sharp spines projecting from the dorsal surfaces of their bodies and numerous arms (7-23, a notable exception to the usual 5 arms). These spines are covered with a 3-layered integument that, in turn, is associated with glandular cells that produce a variety of toxins. Rupture of the overlying integument during spine penetration results in release of a range of bioactive substances capable of causing local and generalized toxicity in humans. Other starfish potentially capable of envenomation include members of the genus Echinaster, which possess thorny spines and small pits from which toxins are secreted, and Plectaster and Solaster species, which are reported to cause contact dermatitis.

Sea urchins (Echinoidea) capable of causing venomous injuries in humans use specialized spines (long or short) and pedicellaria (delicate seizing organs equipped with pincerlike jaws) to deliver their venom. Although both structures are present, generally only one is venomous in a given species. Thus, grouping the venomous urchins into one of the following three categories is convenient:

Long-spined species may inject venom during a puncture with rupture of the overlying integument (Diadema species; see the image below) or with fracture and release of venom from hollow-lumen spines (Echinothrix species).

Echinoderm envenomations. Long-spined sea urchins, such as this Diadema species, inflict an acutely painful penetrating injury that may be accompanied by systemic symptoms and chronic wound sequelae. Photo courtesy of Dee Scarr.

Echinoderm envenomations. Long-spined sea urchins, such as this Diadema species, inflict an acutely painful penetrating injury that may be accompanied by systemic symptoms and chronic wound sequelae. Photo courtesy of Dee Scarr.

Short-spined species similarly may envenom during puncture when downward pressure ruptures the surrounding integument (Phormosoma species), or they may deliver a severe sting without puncture via venom glands located at the spine tips (Asthenosoma species, Araeosoma species).

Species with pedicellaria include those reputed to be the most venomous of all sea urchins, the flower urchin (Toxopneustes pileolus), and others that are less venomous (Tripneustes species). Pedicellaria are small, delicate, tripled-jawed seizing organs that are supported by a long stalk and interspersed among numerous nonvenomous spines. Fanglike appendages are associated with venom glands at the tips of each jaw. The fangs are capable of penetrating skin and may be difficult to dislodge because the valve muscles tightly close each jaw. Pedicellaria continue envenoming even when detached from the urchin body and, thus, should be removed promptly.

Sea cucumbers (Holothuroidea) are generally regarded as nonvenomous, although many are poisonous to eat without proper preparation. The Cuvierian tubules of some sea cucumbers are toxic and may be extruded from the anus as a defensive mechanism when the animal is disturbed or irritated (Bohadschia argus; see the image below).

Echinoderm envenomations. The common and toxic sea cucumber, Bohadschia argus, with extruded Cuvierian tubules. Contact with these sticky white tentaclelike organs or their free-floating fragments may result in intense skin or ocular irritation. Photo courtesy of Paul S. Auerbach, MD.

Echinoderm envenomations. The common and toxic sea cucumber, Bohadschia argus, with extruded Cuvierian tubules. Contact with these sticky white tentaclelike organs or their free-floating fragments may result in intense skin or ocular irritation. Photo courtesy of Paul S. Auerbach, MD.

According to some sources, skin contact may trigger a vigorous inflammatory reaction. [2, 3] However, other experts attest to island customs in which Cuvierian tubules are applied for the relief of coral cuts (A. M. Kerr, Yale University, written communication, March 1999; G. Paulay, Guam University, written communication, March 1999). Accounts of blindness following eye contact are poorly substantiated, [4] although intense conjunctivitis or keratitis may occur.

Epidemiology

United States

Echinoderm envenomations do not represent a significant public health problem, although little epidemiologic data are available. Venomous echinoderms are encountered principally in tropical seas. Nonvenomous traumatic injuries from echinoderms are not uncommon in the United States, especially in coastal communities where sea urchins live.

From 2010-2011, the American Association of Poison Control Centers reported around 1800 sea urchin exposures with approximately 500 of these requiring medical treatment. [5]

International

Echinoderm envenomations are quite common, although little epidemiologic data are available.

The most common starfish envenomization results from contact with the crown-of-thorns starfish (Acanthaster planci), which populates reefs of the Indo-Pacific from east Africa to Central America. Similarly, sea urchins capable of envenomation tend to be concentrated in tropical and subtropical marine regions. The Indo-Pacific is the home of all categories of venomous urchins, including Diadema, Echinothrix, and Toxopneustes species and the venomous genera of sea cucumbers (Holothuria). For some Chinese, Malay, and Pacific Island gourmets, properly prepared sea cucumbers are prized as a delicacy (eg, beche-de-mer, trepang).

As the oceans acidify and water temperatures rise due to climate change, some experts predict an increase in the amount of venomous echinoderm encounters. Many echinoderms are thermophiles, such as D setosum (long-spined sea urchin), and human exposures are likely to rise in the coming years as echinoderm populations increase. [6, 7]

Prognosis

Significant local and systemic effects are possible following echinoderm envenomation from any of the 3 venomous classes, starfish (Asteroidea), sea urchins (Echinoidea), and sea cucumbers (Holothuroidea). However, a clear link between echinoderm envenomation and death (other than subsequent drowning) cannot be found in the literature, despite several anecdotal reports of fatalities. [3, 8, 9, 10] Detailed documentation is sparse, and death must be very rare. This is in contrast to poisoning or intoxication following ingestion of certain echinoderms, which has been well-documented to result in severe illness and fatality.

-

Echinoderm envenomations. Close-up of brittle star arm. Although spiny, members belonging to this class (Ophiuroidea) generally are considered harmless. Of the phylum Echinodermata, only starfish (class Asteroidea), sea urchins (class Echinoidea), and sea cucumbers (class Holothuroidea) are capable of envenomation. Photo courtesy of Scott A. Gallagher, MD.

-

Echinoderm envenomations. Unlike most starfish that are typically pentamerous, the crown-of-thorns starfish (Acanthaster planci) may have as many as 23 arms and a body disc up to 60 cm in diameter. Photo courtesy of Dee Scarr.

-

Echinoderm envenomations. Detail of the crown-of-thorns starfish (Acanthaster planci) spines, which may grow to 6 cm in length. Photo courtesy of Dee Scarr.

-

Echinoderm envenomations. Detail of the crown-of-thorns starfish (Acanthaster planci). Photo courtesy of Scott A. Gallagher, MD.

-

Echinoderm envenomations. The common and toxic sea cucumber, Bohadschia argus, with extruded Cuvierian tubules. Contact with these sticky white tentaclelike organs or their free-floating fragments may result in intense skin or ocular irritation. Photo courtesy of Paul S. Auerbach, MD.

-

Echinoderm envenomations. Long-spined sea urchins, such as this Diadema species, inflict an acutely painful penetrating injury that may be accompanied by systemic symptoms and chronic wound sequelae. Photo courtesy of Dee Scarr.